Histone

In

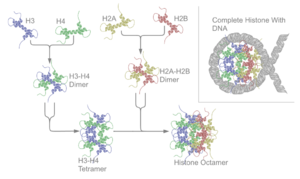

There are five families of histones which are designated H1/H5 (linker histones), H2, H3, and H4 (core histones). The nucleosome core is formed of two H2A-H2B

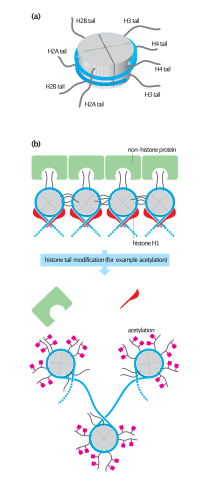

Histones may be chemically modified through the action of enzymes to regulate gene transcription. The most common modification are the methylation of arginine or lysine residues or the acetylation of lysine. Methylation can affect how other protein such as transcription factors interact with the nucleosomes. Lysine acetylation eliminates a positive charge on lysine thereby weakening the electrostatic attraction between histone and DNA resulting in partial unwinding of the DNA making it more accessible for gene expression.

Classes and variants

Five major families of histone proteins exist: H1/H5, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4.[2][4][5][6] Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 are known as the core or nucleosomal histones, while histones H1/H5 are known as the linker histones.

The core histones all exist as

Histones are subdivided into canonical replication-dependent histones, whose genes are expressed during the

The following is a list of human histone proteins, genes and pseudogenes:[10]

| Super family | Family | Replication-dependent genes | Replication-independent genes | Pseudogenes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linker | H1 | H1-6

|

H1-10

|

H1-9P, H1-12P |

| Core | H2A | H2AC25

|

H2AB3, H2AP , H2AL1Q, H2AL3

|

H2AC2P, H2AC3P, H2AC5P, H2AC9P, H2AC10P, H2AQ1P, H2AL1MP |

| H2B | H2BC26, H2BC12L

|

H2BW2 , H2BW3P, H2BN1

|

H2BC2P, H2BC16P, H2BC19P, H2BC20P, H2BC27P, H2BL1P, H2BW3P, H2BW4P | |

| H3 | H3-4

|

H3-7, H3Y1, H3Y2, CENPA

|

H3C5P, H3C9P, H3P16, H3P44 | |

| H4 | H4C14, H4C15

|

H4C16

|

H4C10P |

Structure

The

Archaeal histone only contains a H3-H4 like dimeric structure made out of a single type of unit. Such dimeric structures can stack into a tall superhelix ("hypernucleosome") onto which DNA coils in a manner similar to nucleosome spools.[17] Only some archaeal histones have tails.[18]

The distance between the spools around which eukaryotic cells wind their DNA has been determined to range from 59 to 70 Å.[19]

In all, histones make five types of interactions with DNA:

- Salt bridges and hydrogen bonds between side chains of basic amino acids (especially lysine and arginine) and phosphate oxygens on DNA

- Helix-dipoles form alpha-helixes in H2B, H3, and H4 cause a net positive charge to accumulate at the point of interaction with negatively charged phosphate groups on DNA

- Hydrogen bonds between the DNA backbone and the amidegroup on the main chain of histone proteins

- Nonpolar interactions between the histone and deoxyribose sugars on DNA

- Non-specific minor groove insertions of the H3 and H2B N-terminal tails into two minor grooves each on the DNA molecule

The highly basic nature of histones, aside from facilitating DNA-histone interactions, contributes to their water solubility.

Histones are subject to post translational modification by enzymes primarily on their N-terminal tails, but also in their globular domains.[20][21] Such modifications include methylation, citrullination, acetylation, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, ubiquitination, and ADP-ribosylation. This affects their function of gene regulation.

In general,

Evolution and species distribution

Core histones are found in the

It has been proposed that core histone proteins are evolutionarily related to the helical part of the extended AAA+ ATPase domain, the C-domain, and to the N-terminal substrate recognition domain of Clp/Hsp100 proteins. Despite the differences in their topology, these three folds share a homologous helix-strand-helix (HSH) motif.

Archaeal histones may well resemble the evolutionary precursors to eukaryotic histones.

There are some variant forms in some of the major classes. They share amino acid sequence homology and core structural similarity to a specific class of major histones but also have their own feature that is distinct from the major histones. These minor histones usually carry out specific functions of the chromatin metabolism. For example, histone H3-like CENPA is associated with only the centromere region of the chromosome. Histone H2A variant H2A.Z is associated with the promoters of actively transcribed genes and also involved in the prevention of the spread of silent heterochromatin.[28] Furthermore, H2A.Z has roles in chromatin for genome stability.[29] Another H2A variant H2A.X is phosphorylated at S139 in regions around double-strand breaks and marks the region undergoing DNA repair.[30] Histone H3.3 is associated with the body of actively transcribed genes.[31]

Function

Compacting DNA strands

Histones act as spools around which DNA winds. This enables the compaction necessary to fit the large genomes of eukaryotes inside cell nuclei: the compacted molecule is 40,000 times shorter than an unpacked molecule.

Chromatin regulation

Histones undergo

The common nomenclature of histone modifications is:

- The name of the histone (e.g., H3)

- The single-letter amino acid abbreviation (e.g., K for Lysine) and the amino acid position in the protein

- The type of modification (Me: acetyl, Ub: ubiquitin)

- The number of modifications (only Me is known to occur in more than one copy per residue. 1, 2 or 3 is mono-, di- or tri-methylation)

So

| Type of modification |

Histone | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4 | H3K9 | H3K14 | H3K27 | H3K79 | H3K36 | H4K20 | H2BK5 | H2BK20 | |

| mono-methylation | activation[35] | activation[36] | activation[36] | activation[36][37] | activation[36] | activation[36] | |||

| di-methylation | repression[38] | repression[38] | activation[37] | ||||||

| tri-methylation | activation[39] | repression[36] | repression[36] | activation,[37] repression[36] |

activation | repression[38] | |||

| acetylation | activation[40] | activation[39] | activation[39] | activation[41] | activation | ||||

Modification

A huge catalogue of histone modifications have been described, but a functional understanding of most is still lacking. Collectively, it is thought that histone modifications may underlie a histone code, whereby combinations of histone modifications have specific meanings. However, most functional data concerns individual prominent histone modifications that are biochemically amenable to detailed study.

Chemistry

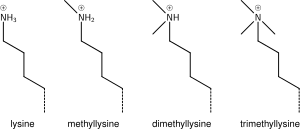

Lysine methylation

The addition of one, two, or many methyl groups to lysine has little effect on the chemistry of the histone; methylation leaves the charge of the lysine intact and adds a minimal number of atoms so steric interactions are mostly unaffected. However, proteins containing Tudor, chromo or PHD domains, amongst others, can recognise lysine methylation with exquisite sensitivity and differentiate mono, di and tri-methyl lysine, to the extent that, for some lysines (e.g.: H4K20) mono, di and tri-methylation appear to have different meanings. Because of this, lysine methylation tends to be a very informative mark and dominates the known histone modification functions.

Glutamine serotonylation

Recently it has been shown, that the addition of a serotonin group to the position 5 glutamine of H3, happens in serotonergic cells such as neurons. This is part of the differentiation of the serotonergic cells. This post-translational modification happens in conjunction with the H3K4me3 modification. The serotonylation potentiates the binding of the general transcription factor TFIID to the TATA box.[42]

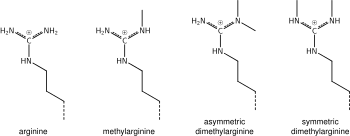

Arginine methylation

What was said above of the chemistry of lysine methylation also applies to arginine methylation, and some protein domains—e.g., Tudor domains—can be specific for methyl arginine instead of methyl lysine. Arginine is known to be mono- or di-methylated, and methylation can be symmetric or asymmetric, potentially with different meanings.

Arginine citrullination

Enzymes called peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs) hydrolyze the imine group of arginines and attach a keto group, so that there is one less positive charge on the amino acid residue. This process has been involved in the activation of gene expression by making the modified histones less tightly bound to DNA and thus making the chromatin more accessible.[43] PADs can also produce the opposite effect by removing or inhibiting mono-methylation of arginine residues on histones and thus antagonizing the positive effect arginine methylation has on transcriptional activity.[44]

Lysine acetylation

Addition of an acetyl group has a major chemical effect on lysine as it neutralises the positive charge. This reduces electrostatic attraction between the histone and the negatively charged DNA backbone, loosening the chromatin structure; highly acetylated histones form more accessible chromatin and tend to be associated with active transcription. Lysine acetylation appears to be less precise in meaning than methylation, in that histone acetyltransferases tend to act on more than one lysine; presumably this reflects the need to alter multiple lysines to have a significant effect on chromatin structure. The modification includes H3K27ac.

Serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphorylation

Addition of a negatively charged phosphate group can lead to major changes in protein structure, leading to the well-characterised role of phosphorylation in controlling protein function. It is not clear what structural implications histone phosphorylation has, but histone phosphorylation has clear functions as a post-translational modification, and binding domains such as BRCT have been characterised.

Effects on transcription

Most well-studied histone modifications are involved in control of transcription.

Actively transcribed genes

Two histone modifications are particularly associated with active transcription:

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3)

- This trimethylation occurs at the promoter of active genesRNA polymerase II C terminal domain (CTD). The same enzyme that phosphorylates the CTD also phosphorylates the Rad6 complex,[51][52] which in turn adds a ubiquitin mark to H2B K123 (K120 in mammals).[53] H2BK123Ub occurs throughout transcribed regions, but this mark is required for COMPASS to trimethylate H3K4 at promoters.[54][55]

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 36 (H3K36me3)

- This trimethylation occurs in the body of active genes and is deposited by the methyltransferase Set2.[56] This protein associates with elongating RNA polymerase II, and H3K36Me3 is indicative of actively transcribed genes.[57] H3K36Me3 is recognised by the Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex, which removes acetyl modifications from surrounding histones, increasing chromatin compaction and repressing spurious transcription.[58][59][60] Increased chromatin compaction prevents transcription factors from accessing DNA, and reduces the likelihood of new transcription events being initiated within the body of the gene. This process therefore helps ensure that transcription is not interrupted.

Repressed genes

Three histone modifications are particularly associated with repressed genes:

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3)

- This histone modification is deposited by the polycomb complex, PRC1, can bind H3K27me3[62] and adds the histone modification H2AK119Ub which aids chromatin compaction.[63][64] Based on this data it appears that PRC1 is recruited through the action of PRC2, however, recent studies show that PRC1 is recruited to the same sites in the absence of PRC2.[65][66]

- Di and tri-methylation of H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2/3)

- H3K9me2/3 is a well-characterised marker for centromeric repeats.[67] RITS recruits the Clr4 histone methyltransferase which deposits H3K9me2/3.[68] This process is called histone methylation. H3K9Me2/3 serves as a binding site for the recruitment of Swi6 (heterochromatin protein 1 or HP1, another classic heterochromatin marker)[69][70] which in turn recruits further repressive activities including histone modifiers such as histone deacetylases and histone methyltransferases.[71]

- Trimethylation of H4 lysine 20 (H4K20me3)

- This modification is tightly associated with heterochromatin,[72][73] although its functional importance remains unclear. This mark is placed by the Suv4-20h methyltransferase, which is at least in part recruited by heterochromatin protein 1.[72]

Bivalent promoters

Analysis of histone modifications in embryonic stem cells (and other stem cells) revealed many gene promoters carrying both H3K4Me3 and H3K27Me3, in other words these promoters display both activating and repressing marks simultaneously. This peculiar combination of modifications marks genes that are poised for transcription; they are not required in stem cells, but are rapidly required after differentiation into some lineages. Once the cell starts to differentiate, these bivalent promoters are resolved to either active or repressive states depending on the chosen lineage.[74]

Other functions

DNA damage repair

Marking sites of DNA damage is an important function for histone modifications. Without a repair marker, DNA would get destroyed by damage accumulated from sources such as the

- Phosphorylation of H2AX at serine 139 (γH2AX)

- Phosphorylated H2AX (also known as gamma H2AX) is a marker for DNA double strand breaks,[75] and forms part of the response to DNA damage.[30][76] H2AX is phosphorylated early after detection of DNA double strand break, and forms a domain extending many kilobases either side of the damage.[75][77][78] Gamma H2AX acts as a binding site for the protein MDC1, which in turn recruits key DNA repair proteins[79] (this complex topic is well reviewed in[80]) and as such, gamma H2AX forms a vital part of the machinery that ensures genome stability.

- Acetylation of H3 lysine 56 (H3K56Ac)

- H3K56Acx is required for genome stability.[81][82] H3K56 is acetylated by the p300/Rtt109 complex,[83][84][85] but is rapidly deacetylated around sites of DNA damage. H3K56 acetylation is also required to stabilise stalled replication forks, preventing dangerous replication fork collapses.[86][87] Although in general mammals make far greater use of histone modifications than microorganisms, a major role of H3K56Ac in DNA replication exists only in fungi, and this has become a target for antibiotic development.[88]

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 36 (H3K36me3)

- H3K36me3 has the ability to recruit the MSH2-MSH6 (hMutSα) complex of the DNA mismatch repair pathway.[89] Consistently, regions of the human genome with high levels of H3K36me3 accumulate less somatic mutations due to mismatch repair activity.[90]

Chromosome condensation

- Phosphorylation of H3 at serine 10 (phospho-H3S10)

- The mitotic kinase aurora B phosphorylates histone H3 at serine 10, triggering a cascade of changes that mediate mitotic chromosome condensation.[91][92] Condensed chromosomes therefore stain very strongly for this mark, but H3S10 phosphorylation is also present at certain chromosome sites outside mitosis, for example in pericentric heterochromatin of cells during G2. H3S10 phosphorylation has also been linked to DNA damage caused by R-loop formation at highly transcribed sites.[93]

- Phosphorylation H2B at serine 10/14 (phospho-H2BS10/14)

- Phosphorylation of H2B at serine 10 (yeast) or serine 14 (mammals) is also linked to chromatin condensation, but for the very different purpose of mediating chromosome condensation during apoptosis.[94][95] This mark is not simply a late acting bystander in apoptosis as yeast carrying mutations of this residue are resistant to hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptotic cell death.

Addiction

Epigenetic modifications of histone tails in specific regions of the brain are of central importance in addictions.[96][97][98] Once particular epigenetic alterations occur, they appear to be long lasting "molecular scars" that may account for the persistence of addictions.[96]

About 7% of the US population is addicted to alcohol. In rats exposed to alcohol for up to 5 days, there was an increase in histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation in the pronociceptin promoter in the brain amygdala complex. This acetylation is an activating mark for pronociceptin. The nociceptin/nociceptin opioid receptor system is involved in the reinforcing or conditioning effects of alcohol.[103]

Synthesis

The first step of chromatin structure duplication is the synthesis of histone proteins: H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4. These proteins are synthesized during S phase of the cell cycle. There are different mechanisms which contribute to the increase of histone synthesis.

Yeast

Yeast carry one or two copies of each histone gene, which are not clustered but rather scattered throughout chromosomes. Histone gene transcription is controlled by multiple gene regulatory proteins such as transcription factors which bind to histone promoter regions. In budding yeast, the candidate gene for activation of histone gene expression is SBF. SBF is a transcription factor that is activated in late G1 phase, when it dissociates from its repressor Whi5. This occurs when Whi5 is phosphorylated by Cdc8 which is a G1/S Cdk.[107] Suppression of histone gene expression outside of S phases is dependent on Hir proteins which form inactive chromatin structure at the locus of histone genes, causing transcriptional activators to be blocked.[108][109]

Metazoan

In

Link between cell-cycle control and synthesis

Nuclear protein Ataxia-Telangiectasia (NPAT), also known as nuclear protein coactivator of histone transcription, is a transcription factor which activates histone gene transcription on chromosomes 1 and 6 of human cells. NPAT is also a substrate of cyclin E-Cdk2, which is required for the transition between G1 phase and S phase. NPAT activates histone gene expression only after it has been phosphorylated by the G1/S-Cdk cyclin E-Cdk2 in early S phase.[114] This shows an important regulatory link between cell-cycle control and histone synthesis.

History

Histones were discovered in 1884 by Albrecht Kossel.[115] The word "histone" dates from the late 19th century and is derived from the German word "Histon", a word itself of uncertain origin, perhaps from Ancient Greek ἵστημι (hístēmi, “make stand”) or ἱστός (histós, “loom”).

In the early 1960s, before the types of histones were known and before histones were known to be highly conserved across taxonomically diverse organisms,

Also in the 1960s, Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had suggested, based on their analyses of histones, that acetylation and methylation of histones could provide a transcriptional control mechanism, but did not have available the kind of detailed analysis that later investigators were able to conduct to show how such regulation could be gene-specific.[121] Until the early 1990s, histones were dismissed by most as inert packing material for eukaryotic nuclear DNA, a view based in part on the models of Mark Ptashne and others, who believed that transcription was activated by protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions on largely naked DNA templates, as is the case in bacteria.

During the 1980s, Yahli Lorch and Roger Kornberg[122] showed that a nucleosome on a core promoter prevents the initiation of transcription in vitro, and Michael Grunstein[123] demonstrated that histones repress transcription in vivo, leading to the idea of the nucleosome as a general gene repressor. Relief from repression is believed to involve both histone modification and the action of chromatin-remodeling complexes. Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had earlier proposed a role of histone modification in transcriptional activation,[124] regarded as a molecular manifestation of epigenetics. Michael Grunstein[125] and David Allis[126] found support for this proposal, in the importance of histone acetylation for transcription in yeast and the activity of the transcriptional activator Gcn5 as a histone acetyltransferase.

The discovery of the H5 histone appears to date back to the 1970s,

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-00-722134-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7167-4339-2.

- PMID 11893489.

- ^ a b "Histone Variants Database 2.0". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ PMID 16472024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-86720-090-4.

- PMID 16209651.

- ^

- ISBN 978-0-915274-84-0.

- ^ PMID 36180920.

- PMID 26159997.

- PMID 26989147.

- PMID 28096900.

- PMID 6326092.

- S2CID 42454232.

- ^ PMID 17391511.

- PMID 28798133.

- ^ PMID 30212449.

- PMID 19138067.

- PMID 16714444.

- S2CID 2956823.

- ISBN 9781118059814.

- PMID 12974611.

- PMID 23257187.

- S2CID 10089116.

- S2CID 204813634.

- PMID 1297351.

- PMID 16248679.

- PMID 22027408.

- ^ PMID 10959836.

- PMID 12086617.

- S2CID 4418993.

- S2CID 1883924.

- PMID 21927517.

- PMID 17713579.

- ^ PMID 17512414.

- ^ PMID 18285465.

- ^ PMID 19335899.

- ^ PMID 17567990.

- PMID 21483810.

- PMID 21106759.

- PMID 30867594.

- PMID 24463520.

- PMID 15339660.

- PMID 12667454.

- PMID 12667453.

- PMID 15680324.

- PMID 11805083.

- PMID 11742990.

- PMID 11752412.

- PMID 16307922.

- PMID 11953320.

- PMID 10642555.

- S2CID 4338471.

- PMID 12070136.

- PMID 11839797.

- PMID 12381723.

- PMID 16286007.

- PMID 16286008.

- PMID 16364921.

- PMID 12435631.

- ^ S2CID 6265267.

- PMID 15525528.

- S2CID 4344378.

- PMID 22325148.

- PMID 22325352.

- PMID 14704433.

- S2CID 205008015.

- S2CID 4334447.

- S2CID 4331863.

- PMID 28135276.

- ^ PMID 15145825.

- PMID 15128874.

- PMID 16630819.

- ^ PMID 9488723.

- PMID 11934988.

- PMID 15458641.

- PMID 10477747.

- S2CID 4410773.

- PMID 21035408.

- PMID 15888442.

- S2CID 4414433.

- PMID 17272722.

- S2CID 19056605.

- PMID 19270680.

- PMID 17690098.

- PMID 22025679.

- PMID 20601951.

- PMID 23622243.

- PMID 28753428.

- S2CID 7698266.

- S2CID 8556959.

- PMID 24211264.

- PMID 12757711.

- PMID 15652479.

- ^ PMID 21989194.

- )

- PMID 20425300.

- ^ "Is nicotine addictive?".

- PMID 22049069.

- S2CID 19157711.

- PMID 11572966.

- S2CID 14013417.

- ^ "What is the scope of methamphetamine abuse in the United States?".

- ^ PMID 26023847.

- PMID 25446457.

- PMID 15210110.

- PMID 1406694.

- PMID 10445029.

- PMID 11782445.

- PMID 14536070.

- PMID 12588979.

- PMID 26997247.

- PMID 10995386.

- ^ Luck JM (1965). "Histone Chemistry: the Pioneers". In Bonner J, Ts'o P (eds.). The Nucleohistones. San Francisco, London, and Amsterdam: Holden-Day, Inc.

- ^ .

- PMID 14036409.

- ^ "Huang R C & Bonner J. Histone, a suppressor of chromosomal RNA synthesis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. US 48:1216-22, 1962" (PDF). Citation Classics (12): 79. 20 March 1978.

- ^ a b James Bonner and Paul T'so (1965) The Nucleohistones. Holden-Day Inc, San Francisco, London, Amsterdam.

- ^ PMID 5388597.

- PMID 14172992.

- S2CID 21270171.

- S2CID 7994350.

- PMID 5219687.

- S2CID 28169631.

- PMID 8601308.

- PMID 689022.