Historiography of the French Revolution

The historiography of the French Revolution stretches back over two hundred years.

Contemporary and 19th-century writings on the Revolution were mainly divided along ideological lines, with conservative historians condemning the Revolution, liberals praising the Revolution of 1789, and radicals defending the democratic and republican values of 1793. By the 20th-century, revolutionary history had become professionalised, with scholars paying more attention to the critical analysis of primary sources from public archives.

From the late 1920s to the 1960s, social and economic interpretations of the Revolution, often from a Marxist perspective, dominated the historiography of the Revolution in France. This trend was challenged by revisionist historians in the 1960s who argued that class conflict was not a major determinant of the course of the Revolution and that political expediency and historical contingency often played a greater role than social factors.

In the 21st-century, no single explanatory model has gained widespread support. The historiography of the revolution has become more diversified, exploring areas such as cultural histories, gender relations, regional histories, visual representations, transnational interpretations, and decolonisation.[1][2] Nevertheless, there persists a very widespread agreement that the French Revolution was the watershed between the premodern and modern eras of Western history.[1]

Contemporary and 19th-century historians

The first writings on the French revolution were near contemporaneous with events and mainly divided along ideological lines. These included Edmund Burke's conservative critique Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) and Thomas Paine's response Rights of Man (1791).[3][4] From 1815, narrative histories dominated, often based on first-hand experience of the revolutionary years. By the mid-19th century, more scholarly histories appeared, written by specialists and based on original documents and a more critical assessment of contemporary accounts.[4]

Dupuy identifies three main strands in 19th-century historiography of the revolution. The first is represented by reactionary writers who rejected the revolutionary ideals of popular sovereignty, civil equality, and the promotion of rationality, progress and personal happiness over religious faith. The second stream is those writers who celebrated the democratic republican values of the revolution. The third stream is those liberal writers, such as Germaine de Staël and Guizot, who accepted the necessity of reforms establishing a constitution and the rights of man, but rejected state interference with private property and individual rights even if supported by a democratic majority.[5] Doyle states that the three streams can be described as the reactionary, the radical and the liberal, or simply right, left and centre.[6]

Burke and Barruel

In

Adolphe Thiers

Kidron describes Thiers' history as: "historical determinism with a romantic aura."[11] Thiers believed that impersonal historical forces were stronger than the will of human actors and that each phase of the Revolution was inevitable. Nevertheless, he distinguished between the positive phase of the Revolution from 1789-91 when the bourgeoisie wrested power from an oppressive and inefficient Old Regime, and the regrettable phase from 1793 when violence and dictatorship were made necessary by war and other circumstances.[11]

François Mignet

François Mignet published his Histoire de la Révolution française in 1824. Writing in the liberal tradition, Mignet saw the Revolution of 1789 as the result of a growing, more prosperous and better educated bourgeoisie which challenged the inequalities of the old regime. The liberal aristocrats and middle classes that led the revolution sought to establish a constitution, representative institutions, and equal political and civil rights.[12][13] Mignet's views on historical necessity were similar to those of Thiers. According to Kidron, Mignet's history is notable for its lack of moral judgment and it presentation of the Terror as the acts of a war government against its enemies.[11]

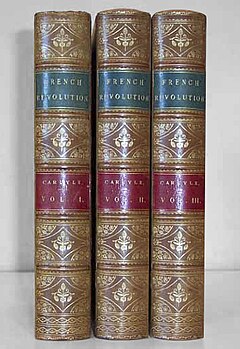

Thomas Carlyle

Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (1798–1874) published his multi-volume Histoire de la Révolution française between 1847 and 1856. Influenced by Vico, MIchelet placed more importance on the masses than individuals.[18] He portrayed the revolution as a spontaneous uprising of the French people against poverty and oppression and in the name of republican equality,[19] and emphasised that the Revolution achieved the unification and legislative reconstruction of France.[18] Michelet was critical of Robespierre and the Jacobins but blamed counter-revolutionaries for provoking the Terror.[20]

Rudé and Doyle place Michelet in the radical, democratic republican tradition,[19] while Kidron describes the work as romantic, liberal and nationalist.[21] François Furet said Michelet's history is, "the cornerstone of all revolutionary historiography and is also a literary monument."[22]

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville's work L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution (The Old Regime and the Revolution,1856) was very influential in the English-speaking world of the 19th-century.[23] Tocqueville was a political liberal who argued that the Revolution was led by thinkers without practical experience who had put too much emphasis on equality over liberty. The democratic egalitarian tendency of the Revolution had laid the groundwork for the destruction of liberty by Napoleon.[24] Tocqueville's contributions to the historiography of the Revolution included his extensive use of the recently opened French archives and his stress that the Revolution had multiple causes, including the King's attempts at reform:[25] "The social order destroyed by a revolution is almost always better than that which immediately precedes it, and experience shows that the most dangerous moment for a bad government is generally that in which it sets about reform."[26]

For Tocqueville, the Revolution was not a result of misery and oppression: education and the economy were growing and ownership of land was becoming more diversified.[27] He emphasised the social structure of the Old Regime, the origins of specific economic and legal grievances, and the continuity of administrative centralisation from the Old Regime to the Revolutionary years.[25]

Hippolyte Taine

Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893) in his Origines de la France contemporaine (1875–94) used archival sources extensively and his interpretation emphasised the role of popular action. His interpretation was conservative and marked by hostility towards the revolution and revolutionary crowds which he claimed were mainly composed of criminal elements.[28][29] He argued that revolutionaries were mainly motivated by the transfer of property, and rejected any distinction between the revolution of 1789 and that of 1793.[30] Historians such as Shafer argue that his interpretation was influenced by his negative experience of the Paris Commune of 1871.[28] He was an admirer of Burke, English conservative principles and "scientific" history based on contemporary documents.[30] He had a major influence on right wing historians of the twentieth century including Augustin Cochin and Pierre Gaxotte.[31]

Other historians

Other significant 19th-century historians of the revolution include:

- Jacobinism.

- Théodore Gosselin (1855–1935) – Better known by the pseudonym "G. Lenotre".

- Albert Sorel (1842–1906) – Diplomatic historian; L'Europe et la Révolution française (8 volumes, 1895–1904); introductory section of this work translated as Europe under the Old Regime (1947).

- Edgar Quinet (1803–1875) – Late Romantic anti-Catholic nationalist.

20th-century

The broad distinction between conservative, democratic-republican and liberal interpretations of the Revolution persisted in the 20th-century, although historiography became more nuanced, with greater attention to critical analysis of documentary evidence.[28][6] From the late 1920s to the 1960s, social and economic analysis of the Revolution, often from a Marxist perspective, dominated the historiography of the Revolution in France. This historical trend has been variously called "Marxist, "classic", "Jacobin" or "history from below" and is associated with historians such as Albert Mathiez, Georges Lefebvre and Albert Soboul.[32][33] From the 1960s, the dominance of social and economic interpretations of the Revolution emphasising class conflict was challenged by revisionist historians such as Alfred Cobban and François Furet.[34]

Jean Jaurès

Jean Jaurès (1859–1914) wrote a three-volume Histoire socialiste de la Révolution française (published 1901-04). He analysed the political, social and economic aspects of the Revolution from a socialist perspective. His thesis was that the Revolution established a bourgeois democratic republic which set the preconditions for the emergence of a socialist movement.[35] His history was also notable for its detailed study of the peasantry and urban poor.[36] As a parliamentarian, he was instrumental in establishing the state-funded "Jaurès Commission", responsible for publishing historical documents and monographs on the Revolution.[28]

Alphonse Aulard and academic studies

Alphonse Aulard (1849–1928) was the first professional historian of the Revolution; he promoted graduate studies, scholarly editions, and learned journals.[37][38] He was appointed to the first National Chair in the History of the French Revolution at the Sorbonne in 1891.[39] He trained advanced students, founded the Société de l'Histoire de la Révolution, edited the scholarly journal La Révolution française, and assembled and published many key primary sources. His major works on the French Revolution include Histoire politique de la Révolution française (A political history of the French revolution, 1901), La Révolution française et le régime féodale (The French revolution and feudalism, 1919) and Le Christianisme et la Révolution française (Christianity and the French Revolution, 1925).[38]

Aulard's historiography was based on positivism. The assumption was that methodology was all-important and the historian's duty was to present in chronological order the duly verified facts, to analyse relations between facts, and provide the most likely interpretation. Full documentation based on research in the primary sources was essential. Aulard's books focused on institutions, public opinion, elections, parties, parliamentary majorities, and legislation.[37] He was a leading historian in the radical tradition, arguing that the democratic republic was the logical culmination of the Revolution. The suspension of the constitution in 1793 and the Terror that followed were necessary expedients to defeat the counter revolution and push through necessary social welfare reforms. Aulard, however, was critical of the excesses of Robespierre, his hero being Danton.[35]

According to Aulard,

From the social point of view, the Revolution consisted in the suppression of what was called the feudal system, in the emancipation of the individual, in greater division of landed property, the abolition of the privileges of noble birth, the establishment of equality, the simplification of life.... The French Revolution differed from other revolutions in being not merely national, for it aimed at benefiting all humanity."[40]

Cochin and Gaxotte

Augustin Cochin (1876–1916) was a conservative critic of the Revolution whose work was influenced by Taine. He argued that there was a continuous tradition linking pre-revolutionary intellectual groups, the freemasons and the Jacobins. His major works include his posthumously published essays Les Sociétés de Pensée et la Démocratie ('Intellectual societies and democracy', published 1921) and La Révolution et la Libre Pensée ('The Revolution and free thought', published 1924). Furet praised Cochin's "rigorous conceptualisation" of the Revolution.[41]

Pierre Gaxotte (1895–1982) was a Royalist critic of the revolution. In his study The French Revolution (1928) he drew on Cochin's work to argue that the Revolution was a conspiracy inspired by pre-revolutionary intellectual societies and was inherently violent from the beginning. The work of Cochin and Gaxotte became the dominant interpretation of the Revolution in Vichy France but fell out of favour after the war.[31]

Albert Mathiez

Albert Mathiez (1874–1932) was a Marxist historian who argued that the Revolution of 1789 was a result of class conflict between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, and was followed by conflict between the bourgeoisie and the sans-culottes, who were a proto-proletariat. He defended Robespierre, arguing that the Terror was necessary to defend the democratic republican revolution and that the Jacobins were overthrown when they tried to carry out a property revolution. The Revolution ended on 9 Thermidor, after which there was only reaction.[42]

Mathiez established the Society for Robespierrist Studies and its journal, the Annales Historiques de la Révolution française. His major works include La Révolution française (3 vol. 1922–1924) and La Vie chère et le movement social sous la Terreur (1927). Mathiez was a leading figure in what came to be known as the Marxist, Jacobin or "classic" school of French revolutionary historiography.[32]

Georges Lefebvre

Georges Lefebvre (1874–1959) was a Marxist historian who wrote detailed studies of the French peasantry (Les paysans du Nord (1924)), The Great Fear of 1789 (1932, first English translation 1973) and revolutionary crowds, as well as a general history of the Revolution La Révolution française (published 1951–1957). He argued that the Revolution represented the triumph of the bourgeoisie and that the Terror was a reaction to an aristocratic plot.[42] He presented the peasantry as active participants in the Revolution who held a fundamentally anti-capitalist worldview.[43]

Lefebvre held the Chair of French Revolution History at the Sorbonne from 1939 until 1955. He mentored a generation of historians who generally wrote cultural, social and economic interpretations defending the achievements of the Revolution. These historians included Albert Soboul, George Rudé, Richard Cobb, and Franco Venturi.[32]

Albert Soboul

Albert Soboul (1914–1982) was a leading Marxist historian who was Chair of French Revolution History at the Sorbonne from 1968 to 1982 and president of the Société des Études Robespierristes.[32] He specialised in the analysis of popular movements during the Revolution and detailed studies of the sans-culottes. In Les Sansculottes Parisiens en l’An II (Paris, 1958; English translation, The Parisian Sans-Culottes and the French Revolution, 1793-4, 1964) he argued that the sans-culottes reflected a popular movement which drove the radicalisation of the Revolution. In his general history of the Revolution (Histoire de la Révolution française, published 1962) he argued that the Revolution represented the culmination of the long economic and social evolution which made the bourgeoisie the dominant class.[13]

Alfred Cobban and revisionist historians

Alfred Cobban (1901–1968) challenged Marxist social and economic explanations of the revolution in two important works, The Myth of the French Revolution (1955) and Social Interpretation of the French Revolution (1964). Cobban argued that the revolution was primarily a political conflict rather than a social one. The revolution wasn't initiated by a rising capitalist bourgeoisie but rather by a declining class of lawyers and office holders, and feudalism had virtually disappeared before the Revolution. The victors of the Revolution were large and small conservative property owners, a result which retarded economic development.[32][44]

American historian George V. Taylor also challenged the class conflict interpretation of the Revolution. In ‘Noncapitalist Wealth and the Origins of the French Revolution’ (1967) and other essays, he argued that there was little economic conflict between the old regime nobility and capitalists and that the share of wealth represented by capitalist enterprises was small. He concluded that the Revolution was not primarily a social one, but a political revolution with social consequences.[45]

Robert Palmer

In The Age of the Democratic Revolution (2 volumes, 1959–64) Robert Palmer argued against "French exceptionalism". He provided a global interpretation of the Revolution, arguing that the revolutionary conflicts of the second half of the 18th-century amounted to an “Atlantic revolution” or “western revolution”.[32] According to Palmer: “All revolutions since 1800, in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa, have learned from the eighteenth-century Revolution of Western Civilization.” David Armitage comments: “That judgment might seem guilty of almost every current scholarly sin—Eurocentrism, essentialism, teleology, diffusionism—but it captured the essence of Palmer’s endeavor: to understand the present through the past with the perspective of the longue durée.”[46]

Palmer's thesis was rejected by both Marxists and French nationalists. Marvin R. Cox states that Marxist historians accused Palmer of "a brief to provide historical legitimacy for NATO," while French nationalists said it diminished the importance of the French Revolution as an historical event.[47][46]

Armitage also criticised Palmer for his omissions: “Its omission of the Haitian Revolution and of Iberian America—not to mention the absence of the enslaved, women, and much cultural history—implied that Palmer was afraid to acknowledge the truly radical elements of the age of revolution, that he was blind to its exclusions and complacent about its failed promises.”[46]

François Furet

François Furet (1927–1997) was a leading French critic of "Jacobin-Marxist" interpretations of the Revolution. In their influential La Revolution française (1965), Furet and Denis Richet argued for the primacy of political decisions, contrasting the reformist period of 1789-91 with the following interventions of the urban masses which led to radicalisation and an ungovernable situation.[34] Furet later argued that a clearer distinction needed to be made between analyses of political events, and of social and economic changes which usually take place over a much longer period than the Jacobin-Marxist school allowed.[48] He also stated that Jacobin-Marxist interpretations of the revolution harboured a totalitarian tendency, and anachronistically viewed the Revolution in the light of the Russian revolution of October 1917.[34] Furet, however, conceded that the Jacobin-Marxist school had increased the understanding of the role of peasants and the urban masses in the revolution.[49] Influenced by Alexis de Tocqueville and Augustin Cochin, Furet argued that the French should stop seeing the revolution as the key to all aspects of modern French history.[50] Other major works by Furet include Penser la Révolution Française (1978; translated as Interpreting the French Revolution 1981) and A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989).[51][52]

Other 20th-century historians

Some other influential historians of this period are:

- Albert Sorel (1842–1906) – Diplomatic historian: Europe et la Révolution française (eight volumes, 1895–1904); introductory section of this work translated as Europe under the Old Regime (1947).

- Ernest Labrousse (1895–1988) – Performed extensive economic research on 18th-century France.

- George Rudé (1910–1993) – Another of Lefebvre's protégés, did further work on the popular side of the Revolution, including: The Crowd in the French Revolution (1959).

- Richard Cobb (1917–1996) was a leading exponent of "history from below" who wrote detailed studies of both provincial and city life, avoiding the revisionism debate by "keeping his nose very close to the ground".[53] His major works include Les armées révolutionnaires (published 1961-63, translated as The People's Armies in 1987).

Modern historiography (1980s to present)

From the 1980s, Western scholars largely abandoned Marxist interpretations of the revolution in terms of bourgeoisie-proletarian class struggle as anachronistic. However, no new explanatory model has gained widespread support.[54][55] The historiography of the revolution has become more diversified, exploring areas such as cultural histories, regional histories, visual representations, transnational interpretations, and decolonisation.[34]

Cultural studies

From the 1980s, there was a proliferation of interpretations based on the study of language and popular culture, in which the Revolution was largely viewed as a symptom of deeper cultural trends.[56] Some of the more prominent works include:

- Robert Darnton The Literary Underground of the Old Regime (1982)

- Keith Michael Baker Inventing the French Revolution (1990)

- R. Chartier, The Cultural Origins of the French Revolution (1991)

- Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution (1984), and The Family Romance of the French Revolution (1992).[57][58]

Women and gender

Late 20th-century studies of women and the revolution emphasised the role of women as participants in the revolution but their exclusion from revolutionary political institutions and full citizenship rights. More recent studies have concentrated on the experiences of specific female groups such as teachers, writers, prostitutes, rural women and those associated with the military and have argued that women were often able to promote new notions of citizenship and challenge gendered power relations.[59] Some key works include:

- Joan B. Landes, Women and the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution (1988)

- Hufton, Olwen, Women and the Limits of Citizenship in the French Revolution (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1992)

- Melzer, S. E. and L. W. Rabine, eds., Rebel Daughters: Women and the French Revolution (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992).

- Godineau, Dominique., The Women of Paris and their French Revolution (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998)

- Jennifer Ngaire Heuer, The Family and the Nation: Gender and Citizenship in Revolutionary France, 1789–1830 (Ithaca, NY, 2005)

Decolonisation

Recent studies of the French colonies have largely abandoned the Jacobin-Marxist approach of classic studies such as C. L. R. James' The Black Jacobins (1938) and Aimé Césaire's Toussaint Louverture: La Révolution française et le problème colonial (1960). Scholars such as Michel-Rolph Traillot and Anthony Hurley have emphasised the cultural traditions of colonial slaves, arguing that the Haitian revolution was not a derivative of the French revolution.[34]

Trans-Atlantic and global histories

Trans-Atlantic and global interpretations of the French Revolution have become a major field of study. Important recent histories include Suzanne Desan, Lynn Hunt, and William Max Nelson (eds), The French Revolution in Global Perspective (Ithaca, NY, 2013); David Armitage and Sanjay Subrahmanyan (eds), The Age of Revolutions in Global Context (Basingstoke, 2010); and Wim Klooster, Revolutions in the Atlantic World; a comparative history (New York, 2009).[60]

Other contemporary historians

- Simon Schama's Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (1989) is a popular narrative history in the revisionist tradition of Cobban and Furet. Schama argues that violence was an essential element of the Revolution from 1789 and that the revolution ended with the fall of Robespierre in 1794.[61]

- William Doyle, a British revisionist historian who wrote The Origins of the French Revolution (1980) and The Oxford History of the French Revolution (2nd edition 2002). Doyle argues that the outbreak of the revolution was a result of political miscalculation rather than social conflicts.[62]

- Timothy Tackett has written a number of histories of the Revolution including When the King Took Flight (2004), Becoming a Revolutionary (2006), and The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution (2015).

Bibliography

Works mentioned, by date of first publication:

- Burke, Edmund (1790). Reflections on the Revolution in France.

- Barruel, Augustin (1797). Mémoires pour servir à l'Histoire du Jacobinisme. Fauche.

- Thiers, Adolphe (1823–1827). Histoire de la Révolution française.

- Mignet, François (1824). Histoire de la Révolution française.

- Guizot, François (1830). Histoire de la civilisation en France. Paris, Pichon.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1837). The French Revolution: A History.

- Michelet, Jules (1847–1856). Histoire de la Révolution française.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de (1856). L'Ancien régime et la révolution. Lévy. Usually translated as The Old Regime and the French Revolution.

- Blanc, Louis (1847–1862). Histoire de la Révolution française.

- Taine, Hippolyte (1875–1893). Origines de la France contemporaine.

- Sorel, Albert (19 April 1895). L'Europe et la Révolution française. Introductory part translated as Europe under the Old Regime (1947).

- Aulard, François-Alphonse. The French Revolution, a Political History, 1789–1804 (4 vol. 3rd ed. 1901; English translation 1910); volume 1 1789–1792 online; Volume 2 1792–95 online

- Mathiez, Albert (1922–27). La Révolution française. Paris, Colin.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1924). Les paysans du Nord.

- Cochin, Augustin (1925). Les Sociétés de pensée et la Révolution en Bretagne.

- Gaxotte, Pierre (1928). La Révolution française.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1932). La Grande Peur de 1789. Translated as The Great Fear of 1789 (1973).

- Lefebvre, Georges (1939). Quatre-Vingt-Neuf. Translated as The Coming of the French Revolution (1947).

- Guérin, Daniel (1946). La lutte de classes sous la Première République.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1957). La Révolution française. Translated in two volumes: The French Revolution from its origins to 1793 (1962), and The French Revolution from 1793 to 1799 (1967).

- Rudé, George (1959). The Crowd in the French Revolution.

- Rudé, George (1988). The French Revolution: Its Causes, Its History and Its Legacy After 200 Years. Grove Press. ISBN 978-1555841508.

- Cobban, Alfred (1963). The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution. Cambridge.

- Cobb, Richard (1968). Les armées révolutionnaires. Translated as The People's Armies (1987).

- Soboul, Albert (1968). Les Sans-Culottes. Translated as The Sans-Culottes (1972).

- Furet, François (1978). Penser la Révolution française. Gallimard. Translated as Interpreting the French Revolution (1981).

- Darnton, Robert (1982). The Literary Underground of the Old Regime.

- Hunt, Lynn (1984). Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. ISBN 9780520052048.

- Doyle, William (1988). Origins of the French Revolution. Oxford.

- Doyle, William (1989). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford.

- Furet, François; Mona Ozouf (1988). Dictionnaire critique de la Révolution Française. Translated as A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989).

- Gauchet, Marcel (1989). La Révolution des droits de l'homme. Gallimard.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Knopf.

- Baker, Keith Michael (1990). Inventing the French Revolution.

- Hunt, Lynn (1992). The Family Romance of the French Revolution.

- Connelly, Owen (1993). The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era.

- Van Kley, Dale K. (1996). The Religious Origins of the French Revolution.

- Godineau, Dominique (1998). The Women of Paris and their French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hufton, Olwen (1999). Women and the Limits of Citizenship in the French Revolution.

- Steel, Mark (2003). Vive La Revolution.

- Tackett, Timothy (2004). When the King Took Flight. ISBN 9780674010543.

- Heuer, Jennifer Ngaire (2005). The Family and the Nation: Gender and Citizenship in Revolutionary France, 1789–1830. New York: Ithaca.

- Tackett, Timothy (2006). Becoming a Revolutionary.

- Heller, Henry (2006). The Bourgeois Revolution in France: 1789–1815.

References

- ^ a b Spang (2003).

- ^ Bell (2004).

- ^ Rudé (1988), pp. 12–14.

- ^ a b Dupuy (2012), pp. 486–487.

- ^ Dupuy (2012), pp. 487–488.

- ^ a b Doyle (2018), p. 440.

- ^ Rudé (1988), p. 12; Doyle (2018), p. 440.

- ISBN 0-582-49314-5.

- ^ De la Croix de Castries (1983), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Guiral (1986), p. 41.

- ^ a b c Kidron (1968), p. 60.

- ^ Rudé (1988), p. 13.

- ^ a b Doyle (2018), p. 444.

- ^ Kidron (1968), pp. 134–136.

- ^ Kidron (1968), pp. 144–145.

- ^ Kidron (1968), p. 146; Doyle (2018), p. 444.

- ^ Kidron (1968), p. 131.

- ^ a b Kidron (1968), p. 213.

- ^ a b Rudé (1988), p. 13; Doyle (2018), pp. 441–442.

- ^ Kidron (1968), p. 218.

- ^ Kidron (1968), p. 192.

- ^ François Furet, Revolutionary France 1770–1880 (1992), p. 571

- ^ Kidron (1968), pp. 219–221.

- ^ Doyle (2018), p. 445.

- ^ a b Kidron (1968), p. 219.

- ^ Tocqueville quoted in Rudé (1968). p. 14

- ^ Rudé (1988), pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d Dupuy (2012), p. 488.

- ^ Rudé (1988), p. 95.

- ^ a b Kidron (1968), pp. 227–229.

- ^ a b Doyle (2018), p. 441.

- ^ a b c d e f Dupuy (2012), p. 489.

- ^ Rudé (1988), pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b c d e Dupuy (2012), p. 490.

- ^ a b Doyle (2018), p. 442.

- ^ Rudé (1988), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Furet & Ozouf (1989), pp. 881–889.

- ^ a b Tendler (2013).

- ^ Tendler (2013), p. 651.

- ^ A. Aulard in Arthur Tilley, ed. (1922). Modern France. A Companion to French Studies. Cambridge UP. p. 115.

- ^ Doyle (2018), pp. 441, 447.

- ^ a b Doyle (2018), p. 443.

- JSTOR 286492.

- ^ Rudé (1988), p. 20.

- ^ Doyle (2018), pp. 445–446.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-16128-0(First published in two volumes 1959-64))

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link - ^ ‘Palmer and Furet: A Reassessment of The Age of the Democratic Revolution’, Historical Reflections

- ^ Rudé (1988), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Rudé (1988), p. 23.

- ^ James Friguglietti and Barry Rothaus, "Interpreting vs. Understanding the Revolution: François Furet and Albert Soboul," Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Proceedings, 1987, (1987) Vol. 17, pp. 23–36

- ^ Claude Langlois, "Furet's Revolution," French Historical Studies, Fall 1990, Vol. 16 Issue 4, pp. 766–76

- ^ Donals Sutherland, "An Assessment of the Writings of François Furet," French Historical Studies, Fall 1990, Vol. 16 Issue 4, pp. 784–91

- ^ David Troyansky, review of Hunt's Politics, Culture, and Class. From The History Teacher, 20, 1 (November 1986), pp. 136–37

- ^ Spang (2003), pp. 119–147.

- ^ Bell (2004), pp. 323–351.

- ^ Doyle (2018), pp. 448–449.

- ^ William H. Sewell. Review of Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution by Lynn Hunt. Theory and Society, 15, 6 (November 1986), pp. 915–17

- ^ Jeff Goodwin. Review of The Family Romance of the French Revolution by Lynn Hunt. Contemporary Sociology, 23, 1 (January 1994), pp. 71–72; quote from Madelyn Gutwirth. "Sacred Father; Profane Sons: Lynn Hunt's French Revolution". French Historical Studies, 19, 2 (Autumn 1995), pp. 261–76

- ^ Desan, Suzanne (2018). "Recent Historiography on the French Revolution and Gender". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 567–69.

- ^ Andress, David, ed. (2015). "Foreword". The Oxford Handbook of the French Revolution (Online ed.). Oxford Academic.

- ^ Doyle (2018), p. 447.

- ^ Doyle (2018), p. 446.

Works cited

- Bell, David A (2004). "Class, consciousness, and the fall of the bourgeois revolution". Critical Review. 16 (2–3): 323–51. S2CID 144241323.

- De la Croix de Castries, René (1983). Monsieur Thiers. Librarie Académique Perrin. ISBN 2-262-00299-1.

- Doyle, William (2018). The Oxford History of the French Revolution (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198804932.

- Dupuy, Pascal (2012). "The Revolution in History, Commemoration, and Memory". In McPhee, Peter (ed.). A Companion to the French Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 486–7. ISBN 9781444335644.

- Furet, François; Ozouf, Mona, eds. (1989). A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Harvard UP. ISBN 9780674177284.

- Guiral, Pierre (1986). Adolphe Thiers ou De la nécessité en politique. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2213018251.

- Kidron, Hedva Ben-Israel (1968). English historians on the French Revolution. London: Oxford University Press.

- Rudé, George (1988). The French Revolution: Its Causes, Its History and Its Legacy After 200 Years. Grove Press. ISBN 978-1555841508.

- Spang, Rebecca L (2003). "Paradigms and Paranoia: How modern Is the French Revolution?". American Historical Review. 108 (1): 119–47. JSTOR 10.1086/533047.

- Tendler, Joseph (2013). "Alphonse Aulard Revisited". European Review of History. 20 (4): 649–69. S2CID 143535928.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Andress, David (2013). "Polychronicon: Interpreting the French Revolution". Teaching History (150): 28–29. JSTOR 43260509.

- Baker, Keith Michael; Joseph Zizek (1998). "The American Historiography of the French Revolution". In Anthony Molho; Gordon S. Wood (eds.). Imagined Histories: American Historians Interpret the Past. Princeton University Press. pp. 349–92.[ISBN missing]

- Bell, David A., and Yair Mintzker, eds. Rethinking the age of revolutions: France and the birth of the modern world (Oxford UP, 2018.

- Bell, David A (Winter 2014). "Questioning the Global Turn: The Case of the French Revolution". French Historical Studies. 37 (1): 1–24. .

- Brinton, Crane (1963). A Decade of Revolution: 1789–1799 (2nd ed.). pp. 293–302.[ISBN missing]

- Cavanaugh, Gerald J (1972). "The Present State of French Revolutionary Historiography: Alfred Cobban and Beyond". French Historical Studies. 7 (4): 587–606. JSTOR 286200.

- Censer, Jack R. (2019). "The French Revolution is Not Over: An Introduction". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 543–44. S2CID 149714265.

- Censer, Jack R. (2019). "Intellectual History and the Causes of the French Revolution". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 545–54. S2CID 150297989.

- Censer, Jack (1999). "Social Twists and Linguistic Turns: Revolutionary Historiography a Decade after the Bicentennial". French Historical Studies. 22 (1): 139–67. JSTOR 286705.

- Censer, Jack (1987). "The Coming of a New Interpretation of the French Revolution". Journal of Social History. 21 (2): 295–309. JSTOR 3788145.

- Cheney, Paul (2019). "The French Revolution's Global Turn and Capitalism's Spatial Fixes". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 575–83. S2CID 85505432.

- Cobban, Alfred (1999). The social interpretation of the French Revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521661515. rejects Marxist models

- Cobban, Alfred (1945). "Historical Revision No CVII. The Beginning of the French Revolution". History. 30 (111): 90–98. JSTOR /24402690. covers the older studies.

- Conner, Susan P. (1990). "In the Shadow of the Guillotine and in the Margins of History: English-Speaking Authors View Women in the French Revolution". Journal of Women's History. 1 (3): 244–60. S2CID 144010907.

- Cox, Marvin R. (1993). "Tocqueville's Bourgeois Revolution". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 19 (3): 279–307. JSTOR 41298973.

- Cox, Marvin R. (2001). "Furet, Cobban and Marx: The Revision of the "Orthodoxy" Revisited". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 27 (1): 49–77. JSTOR 41299194.

- D'Antuono, Giuseppina. "Historiographical heritages: Denis Diderot and the men of the French Revolution." Diciottesimo Secolo 6 (2021): 161-168. online

- Davies, Peter (2006). The Debate on the French Revolution. Manchester University Press.. Basic survey of the historiography[ISBN missing]

- Desan, Suzanne (2019). "Recent Historiography on the French Revolution and Gender". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 566–74. S2CID 149683075.

- Desan, Suzanne (2000). "What's after Political Culture? Recent French Revolutionary Historiography". French Historical Studies. 23 (1): 163–96. S2CID 154870583.

- Desan, Suzanne. "Recent Historiography on the French Revolution and Gender." Journal of Social History 52.3 (2019): 566-574. online

- Disch, Lisa. "How could Hannah Arendt glorify the American Revolution and revile the French? Placing On Revolution in the historiography of the French and American Revolutions." European Journal of Political Theory 10.3 (2011): 350–71.

- Douthwaite, Julia V. “On Seeing the Forest through the Trees: Finding Our Way through Revolutionary Politics, History, and Art.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 43#2 2010, pp. 259–63. online

- Doyle, William. The Oxford history of the French revolution (Oxford UP, 2018).

- Doyle, William (2001). Origins of the French Revolution (3rd ed.). pp. 1–40. ISBN 0198731744.

- Dunne, John. "Fifty Years of Rewriting the French Revolution: Signposts Main Landmarks and Current Directions in the Historiographical Debate," History Review. (1998) pp. 8ff.

- Edelstein, Melvin. The French Revolution and the Birth of Electoral Democracy (Routledge, 2016).

- Ellis, Geoffrey (1978). "The 'Marxist Interpretation' of the French Revolution". The English Historical Review. 93 (367): 353–76. JSTOR 567066.

- Farmer, Paul. France Reviews its Revolutionary Origins (1944) [ISBN missing]

- Friguglietti, James, and Barry Rothaus, "Interpreting vs. Understanding the Revolution: François Furet and Albert Soboul," Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Proceedings, 1987 (1987) Vol. 17, pp. 23–36

- Furet, François and Mona Ozouf, eds. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989), 1120pp; long essays by scholars; strong on history of ideas and historiography (esp pp. 881–1034) excerpt and text search; 17 essays on leading historians, pp. 881–1032

- Furet, François. Interpreting the French revolution (1981). [ISBN missing]

- Germani, Ian, and Robin Swayles. Symbols, myths and images of the French Revolution. University of Regina Publications. 1998. ISBN 978-0-88977-108-6

- Gershoy, Leo. The French Revolution and Napoleon (2nd ed. 1964), scholarly survey [ISBN missing]

- Geyl, Pieter. Napoleon for and Against (1949), 477 pp; reviews the positions of major historians regarding Napoleon

- Guillaume, Lancereau. "Unruly Memory and Historical Order: The Historiography of the French Revolution between Historicism and Presentism (1881-1914)." História da Historiografia: International Journal of Theory and History of Historiography 14.36 (2021): 225-256 online.

- Hanson, Paul R. Contesting the French Revolution (1999), excerpt and text search, combines analytic history and historiography

- Hanson, Paul R. (2019). "Political History of the French Revolution since 1989". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 584–92. S2CID 150289715.

- Heller, Henry. The Bourgeois Revolution in France (1789–1815) (Berghahn Books, 2006) defends Marxist model

- Heuer, Jennifer (2007). "Liberty 'And' Death: The French Revolution". History Compass. 5 (1): 175–200. .

- Hobsbawm, Eric J. Echoes of the Marseillaise: two centuries look back on the French Revolution (Rutgers University Press, 1990) by an English Marxist }

- Hutton, Patrick H. "The role of memory in the historiography of the french revolution." History and Theory 30.1 (1991): 56–69.

- Israel, Jonathan. Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre (2014)

- Jones, Rhys. "Time Warps During the French Revolution." Past & Present 254.1 (2022): 87-125.

- Kafker, Frank A. and James M. Laux, eds. The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations (5th ed. 2002)

- Kaplan, Steven Laurence. Farewell, Revolution: The Historians' Feud, France, 1789/1989 (1996), focus on historians excerpt and text search

- Kaplan, Steven Laurence. Farewell, Revolution: Disputed Legacies, France, 1789/1989 (1995); focus on bitter debates re 200th anniversary excerpt and text search

- Kates, Gary, ed. The French Revolution: Recent Debates and New Controversies (2nd ed. 2005) excerpt and text search

- Kim, Minchul. "Volney and the French Revolution." Journal of the History of Ideas 79.2 (2018): 221–42.

- Langlois, Claude; Tacket, Timothy (1990). "Furet's Revolution". French Historical Studies. 16 (4): 766–76. JSTOR 286319.

- Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate (1993) 142 pp

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the legacy of the French Revolution (Macmillan, 1994)

- McManners, J. "The Historiography of the French Revolution," in A. Goodwin, editor, The New Cambridge Modern History: volume VIII: The American and French Revolutions, 1763–93 (1965) 618–52 online

- McPhee, Peter, ed. (2012). A Companion to the French Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. pp. xv–xxiv. ISBN 9781118316412.

- Maza, Sarah (1989). "Politics, Culture, and the Origins of the French Revolution". The Journal of Modern History. 61 (4): 704–23. S2CID 144366402.

- Parker, Noel. Portrayals of Revolution: Images, Debates and Patterns of thought on the French Revolution (1990) [ISBN missing]

- Root, Hilton L. (1989). "The Case Against George Lefebvre's Peasant Revolution". History Workshop Journal. 28: 88–102. .

- Rigney, Ann. The Rhetoric of Historical Representation: Three Narrative Histories of the French Revolution (Cambridge UP, 2002) covers Alphonse de Lamartine, Jules Michelet and Louis Blanc. [ISBN missing]

- Rosenfeld, Sophia (2019). "The French Revolution in Cultural History". Journal of Social History. 52 (3): 555–65. S2CID 149798697.

- Scott, Samuel F. and Barry Rothaus, eds. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution, 1789–1799 (2 vol 1984), short essays by scholars

- Scott, Michael; Christofferson (1999). "An Antitotalitarian History of the French Revolution: Francois Furet's Penser la Revolution francaise in the Intellectual Politics of the Late 1970s". French Historical Studies. 22 (4): 557–611. S2CID 154051700.

- Skocpol, Theda (1989). "Reconsidering the French Revolution in World-Historical Perspective". Social Research. 56 (1): 53–70. JSTOR 40970534. sociological approach

- Sole, Jacques. "Historiography of the French Revolution," in Michael Bentley, ed. Companion to Historiography (1997) ch 19 pp. 509–25

- Sutherland, Donald (1990). "An Assessment of the Writings of Franco̧is Furet". French Historical Studies. 16 (4): 784–91. JSTOR 286321.

- Tarrow, Sidney. “‘Red of Tooth and Claw’: The French Revolution and the Political Process – Then and Now.” French Politics, Culture & Society 29#1 2011, pp. 93–110. online

- Walton, Charles. "Why the neglect? Social rights and French Revolutionary historiography." French History 33.4 (2019): 503–19.

- Williamson, George S. "Retracing the Sattelzeit: thoughts on the historiography of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras." Central European History 51.1 (2018): 66-74 online.

External links

- French Revolution History in Hindi

- H-France daily discussion email list