Anglo-Saxons

- Afrikaans

- Alemannisch

- العربية

- Asturianu

- Azərbaycanca

- تۆرکجه

- বাংলা

- Bân-lâm-gú

- Беларуская

- Български

- Bosanski

- Brezhoneg

- Català

- Čeština

- Cymraeg

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Eesti

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Frysk

- Gaeilge

- Galego

- 한국어

- Հայերեն

- हिन्दी

- Hrvatski

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- עברית

- ქართული

- Kiswahili

- Latina

- Latviešu

- Lietuvių

- Lingua Franca Nova

- Magyar

- Македонски

- Malagasy

- മലയാളം

- मराठी

- مصرى

- Bahasa Melayu

- Nederlands

- Nedersaksies

- 日本語

- Norsk bokmål

- Norsk nynorsk

- Oʻzbekcha / ўзбекча

- پنجابی

- پښتو

- Plattdüütsch

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Русский

- Саха тыла

- Scots

- Shqip

- Sicilianu

- Simple English

- سنڌي

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Suomi

- Svenska

- தமிழ்

- Taclḥit

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- اردو

- Tiếng Việt

- West-Vlams

- Winaray

- 吴语

- 粵語

- 中文

- ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ ⵜⴰⵏⴰⵡⴰⵢⵜ

| This article is part of the series: |

| Anglo-Saxon society and culture |

|---|

|

| People |

| Language |

| Material culture |

|

| Power and organization |

|

| Religion |

The Anglo-Saxons were a

Historically, the Anglo-Saxon period denotes the period in Britain between about 450 and 1066, after

The history of the Anglo-Saxons is the history of a cultural identity. It developed from divergent groups in association with the people's adoption of Christianity and was integral to the founding of various kingdoms. Threatened by extended Danish

The term Anglo-Saxon began to be used in the 8th century (in Latin and on the continent) to distinguish Germanic language-speaking groups in Britain from those on the continent (Old Saxony and Anglia in Northern Germany).[6][a] In 2003, Catherine Hills summarised the views of many modern scholars in her observation that attitudes towards Anglo-Saxons, and hence the interpretation of their culture and history, have been "more contingent on contemporary political and religious theology as on any kind of evidence."[7]

Ethnonym

The Old English ethnonym Angul-Seaxan comes from the Latin Angli-Saxones and became the name of the peoples the English monk Bede called Angli around 730[8] and the British monk Gildas called Saxones around 530.[9] Anglo-Saxon is a term that was rarely used by Anglo-Saxons themselves.[citation needed] It is likely they identified as ængli, Seaxe or, more probably, a local or tribal name such as Mierce, Cantie, Gewisse, Westseaxe, or Norþanhymbre. After the Viking Age, an Anglo-Scandinavian identity developed in the Danelaw.[10]

The term Angli Saxones seems to have first been used in mainland writing of the 8th century; Paul the Deacon uses it to distinguish the English Saxons from the mainland Saxons (Ealdseaxe, literally, 'old Saxons').[11] The name, therefore, seemed to mean "English" Saxons.

The Christian church seems to have used the word Angli; for example in the story of

The first use of the term Anglo-Saxon amongst the insular sources is in the titles for

The indigenous

Early Anglo-Saxon history (410–660)

The early Anglo-Saxon period covers the history of medieval Britain that starts from the end of

Until AD 400,

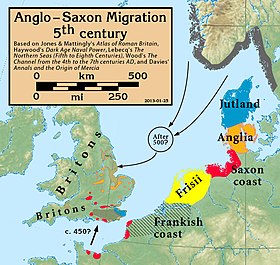

Migration (410–560)

It is now widely accepted that the Anglo-Saxons were not just transplanted Germanic invaders and settlers from the Continent, but the outcome of insular interactions and changes.[26]

Writing c. 540,

Gildas recounts how a war broke out between the Saxons and the local population – historian Nick Higham calls it the "War of the Saxon Federates" – which ended shortly after the siege at 'Mons Badonicus'. The Saxons went back to "their eastern home". Gildas calls the peace a "grievous divorce with the barbarians". The price of peace, Higham argues, was a better treaty for the Saxons, giving them the ability to receive tribute from people across the lowlands of Britain.[29] The archaeological evidence agrees with this earlier timescale. In particular, the work of Catherine Hills and Sam Lucy on the evidence of Spong Hill has moved the chronology for the settlement earlier than 450, with a significant number of items now in phases before Bede's date.[30]

This vision of the Anglo-Saxons exercising extensive political and military power at an early date remains contested. The most developed vision of a continuation in sub-Roman Britain, with control over its own political and military destiny for well over a century, is that of Kenneth Dark,[31] who suggests that the sub-Roman elite survived in culture, politics and military power up to c. 570.[32] Bede, however, identifies three phases of settlement: an exploration phase, when mercenaries came to protect the resident population; a migration phase, which was substantial as implied by the statement that Anglus was deserted; and an establishment phase, in which Anglo-Saxons started to control areas, implied in Bede's statement about the origins of the tribes.[33]

Scholars have not reached a consensus on the number of migrants who entered Britain in this period. Härke argues that the figure is around 100,000 to 200,000.[34] Bryan Ward-Perkins also argues for up to 200,000 incomers.[35] Catherine Hills suggests the number is nearer to 20,000.[36][37] A computer simulation showed that a migration of 250,000 people from mainland Europe could have been accomplished in 38 years.[34] Recent genetic and isotope studies have suggested that the migration, which included both men and women, continued over several centuries,[38][39] possibly allowing for significantly more new arrivals than has been previously thought. By around 500, communities of Anglo-Saxons were established in southern and eastern Britain.[40]

Härke and Michael Wood estimate that the British population in the area that eventually became Anglo-Saxon England was around one million by the start of the fifth century;

Even so, there is general agreement that the kingdoms of

There is evidence for a British influence on the emerging Anglo-Saxon elite classes. The Wessex royal line was traditionally founded by a man named

Recent genetic studies, based on data collected from skeletons found in Iron Age, Roman and Anglo-Saxon era burials, have concluded that the ancestry of the modern English population contains large contributions from both Anglo-Saxon migrants and Romano-British natives.[60][61][62]

Development of an Anglo-Saxon society (560–610)

In the last half of the 6th century, four structures contributed to the development of society; they were the position and freedoms of the ceorl, the smaller tribal areas coalescing into larger kingdoms, the elite developing from warriors to kings, and Irish monasticism developing under Finnian (who had consulted Gildas) and his pupil Columba.

The Anglo-Saxon farms of this period are often falsely supposed to be "peasant farms". However, a

The Tribal Hidage lists thirty-five peoples, or tribes, with assessments in hides, which may have originally been defined as the area of land sufficient to maintain one family.[65] The assessments in the Hidage reflect the relative size of the provinces.[66] Although varying in size, all thirty-five peoples of the Tribal Hidage were of the same status, in that they were areas which were ruled by their own elite family (or royal houses), and so were assessed independently for payment of tribute.[d] By the end of the sixth century, larger kingdoms had become established on the south or east coasts.[68] They include the provinces of the Jutes of Hampshire and Wight, the South Saxons, Kent, the East Saxons, East Angles, Lindsey and (north of the Humber) Deira and Bernicia. Several of these kingdoms may have had as their initial focus a territory based on a former Roman civitas.[69]

By the end of the sixth century, the leaders of these communities were styling themselves kings, though it should not be assumed that all of them were Germanic in origin. The Bretwalda concept is taken as evidence of a number of early Anglo-Saxon elite families. What Bede seems to imply in his Bretwalda is the ability of leaders to extract tribute, overawe and/or protect the small regions, which may well have been relatively short-lived in any one instance. Ostensibly "Anglo-Saxon" dynasties variously replaced one another in this role in a discontinuous but influential and potent roll call of warrior elites.[70] Importantly, whatever their origin or whenever they flourished, these dynasties established their claim to lordship through their links to extended kin, and possibly mythical, ties. As Helen Geake points out, "they all just happened to be related back to Woden".[71]

The process from warrior to cyning – Old English for king – is described in Beowulf:

| Old English | Modern English (as translated by Seamus Heaney) |

|

Oft Scyld Scéfing – sceaþena þréatum |

There was Shield Sheafson, scourge of many tribes, |

Conversion to Christianity (588–686)

In 565, Columba, a monk from Ireland who studied at the monastic school of Moville under St. Finnian, reached Iona as a self-imposed exile. The influence of the monastery of Iona would grow into what Peter Brown has described as an "unusually extensive spiritual empire," which "stretched from western Scotland deep to the southwest into the heart of Ireland and, to the southeast, it reached down throughout northern Britain, through the influence of its sister monastery Lindisfarne."[73]

In June 597 Columba died. At this time,

In 635

In 664, the

Middle Anglo-Saxon history (660–899)

By 660, the political map of Lowland Britain had developed with smaller territories coalescing into kingdoms, and from this time larger kingdoms started dominating the smaller kingdoms. The development of kingdoms, with a particular king being recognised as an overlord, developed out of an early loose structure that, Higham believes, is linked back to the original feodus.[78] The traditional name for this period is the Heptarchy, which has not been used by scholars since the early 20th century[66] as it gives the impression of a single political structure and does not afford the "opportunity to treat the history of any one kingdom as a whole".[79] Simon Keynes suggests that the 8th and 9th century was a period of economic and social flourishing which created stability both below the Thames and above the Humber.[79]

Mercian supremacy (626–821)

Middle-lowland Britain was known as the place of the Mierce, the border or frontier folk, in Latin Mercia. Mercia was a diverse area of tribal groups, as shown by the Tribal Hidage; the peoples were a mixture of Brittonic speaking peoples and "Anglo-Saxon" pioneers and their early leaders had Brittonic names, such as

Mercian military success was the basis of their power; it succeeded against not only 106 kings and kingdoms by winning set-piece battles,[81] but by ruthlessly ravaging any area foolish enough to withhold tribute. There are a number of casual references scattered throughout the Bede's history to this aspect of Mercian military policy. Penda is found ravaging Northumbria as far north as Bamburgh and only a miraculous intervention from Aidan prevents the complete destruction of the settlement.[82] In 676 Æthelred conducted a similar ravaging in Kent and caused such damage in the Rochester diocese that two successive bishops gave up their position because of lack of funds.[83] In these accounts there is a rare glimpse of the realities of early Anglo-Saxon overlordship and how a widespread overlordship could be established in a relatively short period. By the middle of the 8th century, other kingdoms of southern Britain were also affected by Mercian expansionism. The East Saxons seem to have lost control of London, Middlesex and Hertfordshire to Æthelbald, although the East Saxon homelands do not seem to have been affected, and the East Saxon dynasty continued into the ninth century.[84] The Mercian influence and reputation reached its peak when, in the late 8th century, the most powerful European ruler of the age, the Frankish king Charlemagne, recognised the Mercian King Offa's power and accordingly treated him with respect, even if this could have been just flattery.[85]

Learning and monasticism (660–793)

Michael Drout calls this period the "Golden Age", when learning flourished with a renaissance in classical knowledge. The growth and popularity of monasticism was not an entirely internal development, with influence from the continent shaping Anglo-Saxon monastic life.[86] In 669 Theodore, a Greek-speaking monk originally from Tarsus in Asia Minor, arrived in Britain to become the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury. He was joined the following year by his colleague Hadrian, a Latin-speaking African by origin and former abbot of a monastery in Campania (near Naples).[87] One of their first tasks at Canterbury was the establishment of a school; and according to Bede (writing some sixty years later), they soon "attracted a crowd of students into whose minds they daily poured the streams of wholesome learning".[88] As evidence of their teaching, Bede reports that some of their students, who survived to his own day, were as fluent in Greek and Latin as in their native language. Bede does not mention Aldhelm in this connection; but we know from a letter addressed by Aldhelm to Hadrian that he too must be numbered among their students.[89]

Aldhelm wrote in elaborate and grandiloquent and very difficult Latin, which became the dominant style for centuries. Michael Drout states "Aldhelm wrote Latin hexameters better than anyone before in England (and possibly better than anyone since, or at least up until John Milton). His work showed that scholars in England, at the very edge of Europe, could be as learned and sophisticated as any writers in Europe."[90] During this period, the wealth and power of the monasteries increased as elite families, possibly out of power, turned to monastic life.[91]

Anglo-Saxon monasticism developed the unusual institution of the "double monastery", a house of monks and a house of nuns, living next to each other, sharing a church but never mixing, and living separate lives of celibacy. These double monasteries were presided over by abbesses, who became some of the most powerful and influential women in Europe. Double monasteries which were built on strategic sites near rivers and coasts, accumulated immense wealth and power over multiple generations (their inheritances were not divided) and became centers of art and learning.[92]

While Aldhelm was doing his work in Malmesbury, far from him, up in the North of England, Bede was writing a large quantity of books, gaining a reputation in Europe and showing that the English could write history and theology, and do astronomical computation (for the dates of Easter, among other things).

West Saxon hegemony and the Anglo-Scandinavian Wars (793–878)

During the 9th century,

The wealth of the monasteries and the success of Anglo-Saxon society attracted the attention of people from mainland Europe, mostly Danes and Norwegians. Because of the plundering raids that followed, the raiders attracted the name

Viking raids continued until in 850, then the Chronicle says: "The heathen for the first time remained over the winter". The fleet does not appear to have stayed long in England, but it started a trend which others subsequently followed. In particular, the army which arrived in 865 remained over many winters, and part of it later settled what became known as the Danelaw. This was the "Great Army", a term used by the Chronicle in England and by Adrevald of Fleury on the Continent. The invaders were able to exploit the feuds between and within the various kingdoms and to appoint puppet kings, such as Ceolwulf in Mercia in 873 and perhaps others in Northumbria in 867 and East Anglia in 870.[95] The third phase was an era of settlement; however, the "Great Army" went wherever it could find the richest pickings, crossing the English Channel when faced with resolute opposition, as in England in 878, or with famine, as on the Continent in 892.[95] By this stage, the Vikings were assuming ever increasing importance as catalysts of social and political change. They constituted the common enemy, making the English more conscious of a national identity which overrode deeper distinctions; they could be perceived as an instrument of divine punishment for the people's sins, raising awareness of a collective Christian identity; and by 'conquering' the kingdoms of the East Angles, the Northumbrians and the Mercians, they created a vacuum in the leadership of the English people.[99]

Danish settlement continued in Mercia in 877 and East Anglia in 879—80 and 896. The rest of the army meanwhile continued to harry and plunder on both sides of the Channel, with new recruits evidently arriving to swell its ranks, for it clearly continued to be a formidable fighting force.[95] At first, Alfred responded by the offer of repeated tribute payments. However, after a decisive victory at Edington in 878, Alfred offered vigorous opposition. He established a chain of fortresses across the south of England, reorganised the army, "so that always half its men were at home, and half out on service, except for those men who were to garrison the burhs",[100][95] and in 896 ordered a new type of craft to be built which could oppose the Viking longships in shallow coastal waters. When the Vikings returned from the Continent in 892, they found they could no longer roam the country at will, for wherever they went they were opposed by a local army. After four years, the Scandinavians therefore split up, some to settle in Northumbria and East Anglia, the remainder to try their luck again on the Continent.[95]

King Alfred and the rebuilding (878–899)

More important to Alfred than his military and political victories were his religion, his love of learning, and his spread of writing throughout England. Keynes suggests Alfred's work laid the foundations for what really made England unique in all of medieval Europe from around 800 until 1066.[101]

Thinking about how learning and culture had fallen since the last century, King Alfred wrote:

...So completely had wisdom fallen off in England that there were very few on this side of the Humber who could understand their rituals in English, or indeed could translate a letter from Latin into English; and I believe that there were not many beyond the Humber. There were so few of them that I indeed cannot think of a single one south of the Thames when I became king. (Preface: "Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care")[102]

Alfred knew that literature and learning, both in English and in Latin, were very important, but the state of learning was not good when Alfred came to the throne. Alfred saw kingship as a priestly office, a shepherd for his people.[103] One book that was particularly valuable to him was Gregory the Great's Cura Pastoralis (Pastoral Care). This is a priest's guide on how to care for people. Alfred took this book as his own guide on how to be a good king to his people; hence, a good king to Alfred increases literacy. Alfred translated this book himself and explains in the preface:

...When I had learned it I translated it into English, just as I had understood it, and as I could most meaningfully render it. And I will send one to each bishopric in my kingdom, and in each will be an æstel worth fifty mancuses. And I command in God's name that no man may take the æstel from the book nor the book from the church. It is unknown how long there may be such learned bishops as, thanks to God, are nearly everywhere. (Preface: "Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care")[102]

What is presumed to be one of these "æstel" (the word only appears in this one text) is the gold,

Therefore it seems better to me, if it seems so to you, that we also translate certain books ...and bring it about ...if we have the peace, that all the youth of free men who now are in England, those who have the means that they may apply themselves to it, be set to learning, while they may not be set to any other use, until the time when they can well read English writings. (Preface: "Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care")[102]

This began a growth in charters, law, theology and learning. Alfred thus laid the foundation for the great accomplishments of the tenth century and did much to make the vernacular more important than Latin in Anglo-Saxon culture.

I desired to live worthily as long as I lived, and to leave after my life, to the men who should come after me, the memory of me in good works. (Preface: "The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius")[102]

Late Anglo-Saxon history (899–1066)

A framework for the momentous events of the 10th and 11th centuries is provided by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However charters, law-codes and coins supply detailed information on various aspects of royal government, and the surviving works of Anglo-Latin and vernacular literature, as well as the numerous manuscripts written in the 10th century, testify in their different ways to the vitality of ecclesiastical culture. Yet as Keynes suggests "it does not follow that the 10th century is better understood than more sparsely documented periods".[105]

Reform and formation of England (899–978)

During the course of the 10th century, the West Saxon kings extended their power first over Mercia, then into the southern Danelaw, and finally over Northumbria, thereby imposing a semblance of political unity on peoples, who nonetheless would remain conscious of their respective customs and their separate pasts. The prestige, and indeed the pretensions, of the monarchy increased, the institutions of government strengthened, and kings and their agents sought in various ways to establish social order.[106] This process started with Edward the Elder – who with his sister, Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, initially, charters reveal, encouraged people to purchase estates from the Danes, thereby to reassert some degree of English influence in territory which had fallen under Danish control. David Dumville suggests that Edward may have extended this policy by rewarding his supporters with grants of land in the territories newly conquered from the Danes and that any charters issued in respect of such grants have not survived.[107] When Athelflæd died, Mercia was absorbed by Wessex. From that point on there was no contest for the throne, so the house of Wessex became the ruling house of England.[106]

Edward the Elder was succeeded by his son Æthelstan, who Keynes calls the "towering figure in the landscape of the tenth century".[108] His victory over a coalition of his enemies – Constantine, King of the Scots; Owain ap Dyfnwal, King of the Cumbrians; and Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin – at the battle of Brunanburh, celebrated by a poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, opened the way for him to be hailed as the first king of England.[109] Æthelstan's legislation shows how the king drove his officials to do their respective duties. He was uncompromising in his insistence on respect for the law. However this legislation also reveals the persistent difficulties which confronted the king and his councillors in bringing a troublesome people under some form of control. His claim to be "king of the English" was by no means widely recognised.[110] The situation was complex: the Hiberno-Norse rulers of Dublin still coveted their interests in the Danish kingdom of York; terms had to be made with the Scots, who had the capacity not merely to interfere in Northumbrian affairs, but also to block a line of communication between Dublin and York; and the inhabitants of northern Northumbria were considered a law unto themselves. It was only after twenty years of crucial developments following Æthelstan's death in 939 that a unified kingdom of England began to assume its familiar shape. However, the major political problem for Edmund and Eadred, who succeeded Æthelstan, remained the difficulty of subjugating the north.[111] In 959 Edgar is said to have "succeeded to the kingdom both in Wessex and in Mercia and in Northumbria, and he was then 16 years old" (ASC, version 'B', 'C'), and is called "the Peacemaker".[111] By the early 970s, after a decade of Edgar's 'peace', it may have seemed that the kingdom of England was indeed made whole. In his formal address to the gathering at Winchester the king urged his bishops, abbots and abbesses "to be of one mind as regards monastic usage . . . lest differing ways of observing the customs of one Rule and one country should bring their holy conversation into disrepute".[112]

Athelstan's court had been an intellectual incubator. In that court were two young men named Dunstan and Æthelwold who were made priests, supposedly at the insistence of Athelstan, right at the end of his reign in 939.[113] Between 970 and 973 a council was held, under the aegis of Edgar, where a set of rules were devised that would be applicable throughout England. This put all the monks and nuns in England under one set of detailed customs for the first time. In 973, Edgar received a special second, 'imperial coronation' at Bath, and from this point England was ruled by Edgar under the strong influence of Dunstan, Athelwold, and Oswald, the Bishop of Worcester.

Æthelred and the return of the Scandinavians (978–1016)

The reign of King

The increasingly difficult times brought on by the Viking attacks are reflected in both Ælfric's and Wulfstan's works, but most notably in Wulfstan's fierce rhetoric in the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, dated to 1014.[117] Malcolm Godden suggests that ordinary people saw the return of the Vikings as the imminent "expectation of the apocalypse," and this was given voice in Ælfric and Wulfstan writings,[118] which is similar to that of Gildas and Bede. Raids were taken as signs of God punishing his people; Ælfric refers to people adopting the customs of the Danish and exhorts people not to abandon the native customs on behalf of the Danish ones, and then requests a "brother Edward" to try to put an end to a "shameful habit" of drinking and eating in the outhouse, which some of the countrywomen practised at beer parties.[119]

In April 1016, Æthelred died of illness, leaving his son and successor Edmund Ironside to defend the country. The final struggles were complicated by internal dissension, and especially by the treacherous acts of Ealdorman Eadric of Mercia, who opportunistically changed sides to Cnut's party. After the defeat of the English in the Battle of Assandun in October 1016, Edmund and Cnut agreed to divide the kingdom so that Edmund would rule Wessex and Cnut Mercia, but Edmund died soon after his defeat in November 1016, making it possible for Cnut to seize power over all England.[120]

Conquest of England: Danes, Norwegians and Normans (1016–1066)

In the 11th century, there were three conquests: one by Cnut in 1016; the second was an unsuccessful attempt of Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066; and the third was conducted by William of Normandy in 1066. The consequences of each conquest changed the Anglo-Saxon culture. Politically and chronologically, the texts of this period are not Anglo-Saxon; linguistically, those written in English (as opposed to Latin or French, the other official written languages of the period) moved away from the late West Saxon standard that is called "Old English". Yet neither are they "Middle English"; moreover, as Treharne explains, for around three-quarters of this period, "there is barely any 'original' writing in English at all". These factors have led to a gap in scholarship, implying a discontinuity either side of the Norman Conquest, however this assumption is being challenged.[121]

At first sight, there would seem little to debate. Cnut appeared to have adopted wholeheartedly the traditional role of Anglo-Saxon kingship.[122] However an examination of the laws, homilies, wills, and charters dating from this period suggests that as a result of widespread aristocratic death and the fact that Cnut did not systematically introduce a new landholding class, major and permanent alterations occurred in the Saxon social and political structures.[123] Eric John remarks that for Cnut "the simple difficulty of exercising so wide and so unstable an empire made it necessary to practise a delegation of authority against every tradition of English kingship".[124] The disappearance of the aristocratic families which had traditionally played an active role in the governance of the realm, coupled with Cnut's choice of thegnly advisors, put an end to the balanced relationship between monarchy and aristocracy so carefully forged by the West Saxon Kings.

The fall of England and the Norman Conquest is a multi-generational, multi-family succession problem caused in great part by Athelred's incompetence. By the time William of Normandy, sensing an opportunity, landed his invading force in 1066, the elite of Anglo-Saxon England had changed, although much of the culture and society had stayed the same.

Ða com Wyllelm eorl of Normandige into Pefnesea on Sancte Michæles mæsseæfen, sona þæs hi fere wæron, worhton castel æt Hæstingaport. Þis wearð þa Harolde cynge gecydd, he gaderade þa mycelne here, com him togenes æt þære haran apuldran, Wyllelm him com ongean on unwær, ær þis folc gefylced wære. Ac se kyng þeah him swiðe heardlice wið feaht mid þam mannum þe him gelæstan woldon, þær wearð micel wæl geslægen on ægðre healfe. Ðær wearð ofslægen Harold kyng, Leofwine eorl his broðor, Gyrð eorl his broðor, fela godra manna, þa Frencyscan ahton wælstowe geweald.

Then came William, the Earl of Normandy, into Pevensey on the evening of St Michael's mass, and soon as his men were ready, they built a fortress at Hasting's port. This was told to King Harold, and he gathered then a great army and came towards them at the Hoary Apple Tree, and William came upon him unawares before his folk were ready. But the king nevertheless withstood him very strongly with fighting with those men who would follow him, and there was a great slaughter on either side. Then Harald the King was slain, and Leofwine the Earl, his brother, and Gyrth, and many good men, and the Frenchmen held the place of slaughter.[126]

After the Norman Conquest

Following the

The chronicler Orderic Vitalis, who was the product of an Anglo-Norman marriage, writes: "And so the English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed".[135] The inhabitants of the North and Scotland never warmed to the Normans following the Harrying of the North (1069–1070), where William, according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle utterly "ravaged and laid waste that shire".[136]

Many Anglo-Saxon people needed to learn

Old English had been a central mark of the Anglo-Saxon cultural identity. With the passing of time, however, and particularly following the Norman conquest of England, this language changed significantly, and although some people (for example the scribe known as the Tremulous Hand of Worcester) could still read Old English into the thirteenth century, it fell out of use and the texts became useless. The Exeter Book, for example, seems to have been used to press gold leaf and at one point had a pot of fish-based glue sitting on top of it. For Michael Drout this symbolises the end of the Anglo-Saxons.[140]

After 1066, it took more than three centuries for English to replace French as the language of government. The 1362 parliament opened with a speech in English and in the early 15th century, Henry V became the first monarch, since before the 1066 conquest, to use English in his written instructions.[141]

Life and society

The larger narrative, seen in the history of Anglo-Saxon England, is the continued mixing and integration of various disparate elements into one Anglo-Saxon people. The outcome of this mixing and integration was a continuous re-interpretation by the Anglo-Saxons of their society and worldview, which Heinreich Härke calls a "complex and ethnically mixed society".[142]

Kingship and kingdoms

The development of Anglo-Saxon

The later sixth century saw the end of a 'prestige goods' economy, as evidenced by the decline of accompanied burial, and the appearance of the first 'princely' graves and high-status settlements.

By 600, the establishment of the first Anglo-Saxon 'emporia' (alternatively 'wics') appears to have been in process. There are only four major archaeologically attested wics in England – London, Ipswich, York, and Hamwic. These were originally interpreted by Hodges as methods of royal control over the import of prestige goods, rather than centre of actual trade-proper.[147] Despite archaeological evidence of royal involvement, emporia are now widely understood to represent genuine trade and exchange, alongside a return to urbanism.[148]

According to

The most powerful king could be recognised by other rulers as bretwalda (Old English for "ruler of Britain").[150] Bede's use of the term imperium has been seen as significant in defining the status and powers of the bretwaldas, in fact it is a word Bede used regularly as an alternative to regnum; scholars believe this just meant the collection of tribute.[151] Oswiu's extension of overlordship over the Picts and Scots is expressed in terms of making them tributary. Military overlordship could bring great short-term success and wealth, but the system had its disadvantages. Many of the overlords enjoyed their powers for a relatively short period.[f] Foundations had to be carefully laid to turn a tribute-paying under-kingdom into a permanent acquisition, such as Bernician absorption of Deira.[152]

Only five Anglo-Saxon kingdoms are known to have survived to 800, and several British kingdoms in the west of the country had disappeared as well. The major kingdoms had grown through absorbing smaller principalities, and the means through which they did it and the character their kingdoms acquired as a result are one of the major themes of the Middle Saxon period. Beowulf, for all its heroic content, clearly makes the point that economic and military success were intimately linked. A 'good' king was a generous king who through his wealth won the support which would ensure his supremacy over other kingdoms.[153] The smaller kingdoms did not disappear without trace once they were incorporated into larger polities; on the contrary their territorial integrity was preserved when they became ealdormanries or, depending on size, parts of ealdormanries within their new kingdoms. An example of this tendency for later boundaries to preserve earlier arrangements is Sussex; the county boundary is essentially the same as that of the West Saxon shire and the Anglo-Saxon kingdom.[154]

The Witan, also called Witenagemot, was the council of kings; its essential duty was to advise the king on all matters on which he chose to ask its opinion. It attested his grants of land to churches or laymen, consented to his issue of new laws or new statements of ancient custom, and helped him deal with rebels and persons suspected of disaffection.

King Alfred's digressions in his translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy, provided these observations about the resources which every king needed:

In the case of the king, the resources and tools with which to rule are that he have his land fully manned: he must have praying men, fighting men and working men. You know also that without these tools no king may make his ability known. Another aspect of his resources is that he must have the means of support for his tools, the three classes of men. These, then, are their means of support: land to live on, gifts, weapons, food, ale, clothing and whatever else is necessary for each of the three classes of men.[155]

This is the first written appearance of the division of society into the 'three orders'; the 'working men' provided the raw materials to support the other two classes. The advent of Christianity brought with it the introduction of new concepts of land tenure. The role of churchmen was analogous with that of the warriors waging heavenly warfare. However what Alfred was alluding to was that in order for a king to fulfil his responsibilities towards his people, particularly those concerned with defence, he had the right to make considerable exactions from the landowners and people of his kingdom.[156] The need to endow the church resulted in the permanent alienation of stocks of land which had previously only been granted on a temporary basis and introduced the concept of a new type of hereditary land which could be freely alienated and was free of any family claims.[157]

The nobility under the influence of Alfred became involved with developing the cultural life of their kingdom.[158] As the kingdom became unified, it brought the monastic and spiritual life of the kingdom under one rule and stricter control. However the Anglo-Saxons believed in 'luck' as a random element in the affairs of man and so would probably have agreed that there is a limit to the extent one can understand why one kingdom failed while another succeeded.[159] They also believed in 'destiny' and interpreted the fate of the kingdom of England with Biblical and Carolingian ideology, with parallels, between the Israelites, the great European empires and the Anglo-Saxons. Danish and Norman conquests were just the manner in which God punished his sinful people and the fate of great empires.[106]

Religion

Although Christianity dominates the religious history of the Anglo-Saxons, life in the 5th and 6th centuries was dominated by pagan religious beliefs with a Scandinavian-Germanic heritage.

Pagan Anglo-Saxons worshipped at a variety of different sites across their landscape, some of which were apparently specially built

Early Anglo-Saxon society attached great significance to the horse; a horse may have been an acquaintance of the god

Bede's story of Cædmon, the cowherd who became the 'Father of English Poetry,' represents the real heart of the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons from paganism to Christianity. Bede writes, "[t]here was in the Monastery of this Abbess (Streonæshalch – now known as Whitby Abbey) a certain brother particularly remarkable for the Grace of God, who was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of scripture, he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in Old English, which was his native language. By his verse the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven." The story of Cædmon illustrates the blending of Christian and Germanic, Latin and oral tradition, monasteries and double monasteries, pre-existing customs and new learning, popular and elite, that characterizes the Conversion period of Anglo-Saxon history and culture. Cædmon does not destroy or ignore traditional Anglo-Saxon poetry. Instead, he converts it into something that helps the Church. Anglo-Saxon England finds ways to synthesize the religion of the Church with the existing "northern" customs and practices. Thus the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons was not just their switching from one practice to another, but making something new out of their old inheritance and their new belief and learning.[166]

Monasticism, and not just the church, was at the centre of Anglo-Saxon Christian life. Western monasticism, as a whole, had been evolving since the time of the Desert Fathers, but in the seventh century, monasticism in England confronted a dilemma that brought to question the truest representation of the Christian faith. The two monastic traditions were the Celtic and the Roman, and a decision was made to adopt the Roman tradition. Monasteria seem to describe all religious congregations other than those of the bishop.

In the 10th century, Dunstan brought Athelwold to Glastonbury, where the two of them set up a monastery on Benedictine lines. For many years, this was the only monastery in England that strictly followed the Benedictine Rule and observed complete monastic discipline. What Mechthild Gretsch calls an "Aldhelm Seminar" developed at Glastonbury, and the effects of this seminar on the curriculum of learning and study in Anglo-Saxon England were enormous.[113] Royal power was put behind the reforming impulses of Dunstan and Athelwold, helping them to enforce their reform ideas. This happened first at the Old Minster in Winchester, before the reformers built new foundations and refoundations at Thorney, Peterborough, and Ely, among other places. Benedictine monasticism spread throughout England, and these became centers of learning again, run by people trained in Glastonbury, with one rule, the works of Aldhelm at the center of their curricula but also influenced by the vernacular efforts of Alfred. From this mixture sprung a great flowering of literary production.[167]

Fighting and warfare

Soldiers throughout the country were summoned, for both offensive and defensive war; early armies consisted essentially of household bands, while later on men were recruited on a territorial basis. The mustering of an army, annually at times, occupied an important place in Frankish history, both military and constitutional. The English kingdoms appear to have known no institution similar to this. The earliest reference is Bede's account of the overthrow of the Northumbrian Æthelfrith by Rædwald overlord of the southern English. Rædwald raised a large army, presumably from among the kings who accepted his overlordship, and "not giving him time to summon and assemble his whole army, Rædwald met him with a much greater force and slew him on the Mercian border on the east bank of the river Idle."[168] At the Battle of Edington in 878, when the Danes made a surprise attack on Alfred at Chippenham after Twelfth Night, Alfred retreated to Athelney after Easter and then seven weeks after Easter mustered an army at "Egbert's stone".[169] It is not difficult to imagine that Alfred sent out word to the ealdormen to call his men to arms. This may explain the delay, and it is probably no more than coincidence that the army mustered at the beginning of May, a time when there would have been sufficient grass for the horses. There is also information about the mustering of fleets in the eleventh century. From 992 to 1066 fleets were assembled at London, or returned to the city at the end of their service, on several occasions. Where they took up station depended on the quarter from which a threat was expected: Sandwich if invasion was expected from the north, or the Isle of Wight if it was from Normandy.[170]

Once they left home, these armies and fleets had to be supplied with food and clothing for the men as well as forage for the horses. Yet if armies of the seventh and eighth centuries were accompanied by servants and a supply train of lesser free men, Alfred found these arrangements insufficient to defeat the Vikings. One of his reforms was to divide his military resources into thirds. One part manned the burhs and found the permanent garrisons which would make it impossible for the Danes to overrun Wessex, although they would also take to the field when extra soldiers were needed. The remaining two would take it in turns to serve. They were allocated a fixed term of service and brought the necessary provisions with them. This arrangement did not always function well. On one occasion a division on service went home in the middle of blockading a Danish army on Thorney Island; its provisions were consumed and its term had expired before the king came to relieve them.[171] This method of division and rotation remained in force up to 1066. In 917, when armies from Wessex and Mercia were in the field from early April until November, one division went home and another took over. Again, in 1052 when Edward's fleet was waiting at Sandwich to intercept Godwine's return, the ships returned to London to take on new earls and crews.[170] The importance of supply, vital to military success, was appreciated even if it was taken for granted and features only incidentally in the sources.[172]

Military training and strategy are two important matters on which the sources are typically silent. There are no references in literature or laws to men training, and so it is necessary to fall back on inference. For the noble warrior, his childhood was of first importance in learning both individual military skills and the teamwork essential for success in battle. Perhaps the games the youthful Cuthbert played ('wrestling, jumping, running, and every other exercise') had some military significance.[173] Turning to strategy, of the period before Alfred the evidence gives the impression that Anglo-Saxon armies fought battles frequently. Battle was risky and best avoided unless all the factors were on your side. But if you were in a position so advantageous that you were willing to take the chance, it is likely that your enemy would be in such a weak position that he would avoid battle and pay tribute. Battles put the princes' lives at risk, as is demonstrated by the Northumbrian and Mercian overlordships brought to an end by a defeat in the field. Gillingham has shown how few pitched battles Charlemagne and Richard I chose to fight.[174]

A defensive strategy becomes more apparent in the later part of Alfred's reign. It was built around the possession of fortified places and the close pursuit of the Danes to harass them and impede their preferred occupation of plundering. Alfred and his lieutenants were able to fight the Danes to a standstill by their repeated ability to pursue and closely besiege them in fortified camps throughout the country. The fortification of sites at Witham, Buckingham, Towcester and Colchester persuaded the Danes of the surrounding regions to submit.[175] The key to this warfare was sieges and the control of fortified places. It is clear that the new fortresses had permanent garrisons, and that they were supported by the inhabitants of the existing burhs when danger threatened. This is brought out most clearly in the description of the campaigns of 917 in the Chronicle, but throughout the conquest of the Danelaw by Edward and Æthelflæd it is clear that a sophisticated and coordinated strategy was being applied.[176]

In 973, a single currency was introduced into England in order to bring about political unification, but by concentrating bullion production at many coastal mints, the new rulers of England created an obvious target which attracted a new wave of Viking invasions, which came close to breaking up the kingdom of the English. From 980 onwards, the Anglo -Saxon Chronicle records renewed raiding against England. At first, the raids were probing ventures by small numbers of ships' crews, but soon grew in size and effect, until the only way of dealing with the Vikings appeared to be to pay protection money to buy them off: "And in that year [991] it was determined that tribute should first be paid to the Danish men because of the great terror they were causing along the coast. The first payment was 10,000 pounds."[177] The payment of Danegeld had to be underwritten by a huge balance of payments surplus; this could only be achieved by stimulating exports and cutting imports, itself accomplished through currency devaluation. This affected everyone in the kingdom.

Settlements and working life

Helena Hamerow suggests that the prevailing model of working life and settlement, particularly for the early period, was one of shifting settlement and building tribal kinship. The mid-Saxon period saw diversification, the development of enclosures, the beginning of the toft system, closer management of livestock, the gradual spread of the mould-board plough, 'informally regular plots' and a greater permanence, with further settlement consolidation thereafter foreshadowing post-Norman Conquest villages. The later periods saw a proliferation of service features including barns, mills and latrines, most markedly on high-status sites. Throughout the Anglo-Saxon period as Hamerow suggests, "local and extended kin groups remained...the essential unit of production". This is very noticeable in the early period. However, by the tenth and eleventh centuries, the rise of the manor and its significance in terms of both settlement and the management of land, which becomes very evident in the Domesday Book of 1086.[178]

The collection of buildings discovered at Yeavering formed part of an Anglo-Saxon royal vill or king's tun. These 'tun' consisted of a series of buildings designed to provide short-term accommodation for the king and his household. It is thought that the king would have travelled throughout his land dispensing justice and authority and collecting rents from his various estates. Such visits would be periodic, and it is likely that he would visit each royal villa only once or twice per year. The Latin term villa regia which Bede uses of the site suggests an estate centre as the functional heart of a territory held in the king's demesne. The territory is the land whose surplus production is taken into the centre as food-render to support the king and his retinue on their periodic visits as part of a progress around the kingdom. This territorial model, known as a multiple estate or shire, has been developed in a range of studies. Colm O'Brien, in applying this to Yeavering, proposes a geographical definition of the wider shire of Yeavering and also a geographical definition of the principal estate whose structures Hope-Taylor excavated.[179] One characteristic that the king's tun shared with some other groups of places is that it was a point of public assembly. People came together not only to give the king and his entourage board and lodging; but they attended upon the king in order to have disputes settled, cases appealed, lands granted, gifts given, appointments made, laws promulgated, policy debated, and ambassadors heard. People also assembled for other reasons, such as to hold fairs and to trade.[180]

The first creations of towns are linked to a system of specialism at individual settlements, which is evidenced in studying place-names. Sutterton, "shoe-makers' tun" (in the area of the Danelaw such places are Sutterby) was so named because local circumstances allowed the growth of a craft recognised by the people of surrounding places. Similarly with Sapperton, the "soap-makers' tun". While Boultham, the "meadow with burdock plants", may well have developed a specialism in the production of burrs for wool-carding, since meadows with burdock merely growing in them must have been relatively numerous. From places named for their services or location within a single district, a category of which the most obvious perhaps are the Eastons and Westons, it is possible to move outwards to glimpse component settlements within larger economic units. Names betray some role within a system of seasonal pasture, Winderton in Warwickshire is the winter tun and various Somertons are self-explanatory. Hardwicks are dairy farms and Swinhopes the valleys where pigs were pastured.[181]

Settlement patterns as well as village plans in England fall into two great categories: scattered farms and homesteads in upland and woodland Britain, nucleated villages across a swathe of central England.[182] The chronology of nucleated villages is much debated and not yet clear. Yet there is strong evidence to support the view that nucleation occurred in the tenth century or perhaps the ninth, and was a development parallel to the growth of towns.[183]

Women, children and slaves

Alfred's reference to 'praying men, fighting men and working men' is far from a complete description of his society. Women in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms appear to have enjoyed considerable independence, whether as abbesses of the great 'double monasteries' of monks and nuns founded during the seventh and eighth centuries, as major land-holders recorded in Domesday Book (1086), or as ordinary members of society. They could act as principals in legal transactions, were entitled to the same weregild as men of the same class, and were considered 'oath-worthy', with the right to defend themselves on oath against false accusations or claims. Sexual and other offences against them were penalised heavily. There is evidence that even married women could own property independently, and some surviving wills are in the joint names of husband and wife.[184]

Marriage comprised a contract between the woman's family and the prospective bridegroom, who was required to pay a 'bride-price' in advance of the wedding and a 'morning gift' following its consummation. The latter became the woman's personal property, but the former may have been paid to her relatives, at least during the early period. Widows were in a particularly favourable position, with inheritance rights, custody of their children and authority over dependents. However, a degree of vulnerability may be reflected in laws stating that they should not be forced into nunneries or second marriages against their will. The system of primogeniture (inheritance by the first-born male) was not introduced to England until after the Norman Conquest, so Anglo-Saxon siblings – girls as well as boys – were more equal in terms of status.

The age of majority was usually either ten or twelve, when a child could legally take charge of inherited property, or be held responsible for a crime.[185] It was common for children to be fostered, either in other households or in monasteries, perhaps as a means of extending the circle of protection beyond the kin group. Laws also make provision for orphaned children and foundlings.[186]

The traditional distinction in society, amongst free men, was expressed as eorl and ceorl ('earl and churl') though the term 'Earl' took on a more restricted meaning after the Viking period. The noble rank is designated in early centuries as gesiþas ('companions') or þegnas ('thegns'), the latter coming to predominate. After the Norman Conquest the title 'thegn' was equated to the Norman 'baron'.[187] A certain amount of social mobility is implied by regulations detailing the conditions under which a ceorl could become a thegn. Again these would have been subject to local variation, but one text refers to the possession of five hides of land (around 600 acres), a bell and a castle-gate, a seat and a special office in the king's hall. In the context of the control of boroughs, Frank Stenton notes that according to an 11th-century source, "a merchant who had carried out three voyages at his own charge [had also been] regarded as of thegnly status."[188] Loss of status could also occur, as with penal slavery, which could be imposed not only on the perpetrator of a crime but on his wife and family.

A further division in Anglo-Saxon society was between slave and free. Slavery was not as common as in other societies, but appears to have been present throughout the period. Both the freemen and slaves were hierarchically structured, with several classes of freemen and many types of slaves. These varied at different times and in different areas, but the most prominent ranks within free society were the king, the nobleman or thegn, and the ordinary freeman or ceorl. They were differentiated primarily by the value of their weregild or 'man price', which was not only the amount payable in compensation for homicide, but was also used as the basis for other legal formulations such as the value of the oath that they could swear in a court of law. Slaves had no weregild, as offences against them were taken to be offences against their owners, but the earliest laws set out a detailed scale of penalties depending both on the type of slave and the rank of owner.[189] Some slaves may have been members of the native British population conquered by the Anglo-Saxons when they arrived from the continent; others may have been captured in wars between the early kingdoms, or have sold themselves for food in times of famine. However, slavery was not always permanent, and slaves who had gained their freedom would become part of an underclass of freedmen below the rank of ceorl.[190]

Culture

Architecture

Early Anglo-Saxon buildings in Britain were generally simple, not using masonry except in foundations but constructed mainly using timber with

Only ten of the hundreds of settlement sites that have been excavated in England from this period have revealed masonry domestic structures and confined to a few specific contexts. Timber was the natural building medium of the age:[193] the Anglo-Saxon word for "building" is timbe. Unlike in the Carolingian Empire, late Anglo-Saxon royal halls continued to be of timber in the manner of Yeavering centuries before, even though the king could clearly have mustered the resources to build in stone.[194] Their preference must have been a conscious choice, perhaps an expression of deeply–embedded Germanic identity on the part of the Anglo-Saxon royalty.

Even the elite had simple buildings, with a central fire and a hole in the roof to let the smoke escape; the largest homes rarely had more than one floor and one room. Buildings varied widely in size, most were square or rectangular, though some round houses have been found. Frequently these buildings have sunken floors, with a shallow pit over which a plank floor was suspended. The pit may have been used for storage, but more likely was filled with straw for insulation. A variation on the sunken floor design has been found in towns, where the "basement" may be as deep as 9 feet, suggesting a storage or work area below a suspended floor. Another common design was simple post framing, with heavy posts set directly into the ground, supporting the roof. The space between the posts was filled in with wattle and daub, or occasionally, planks. The floors were generally packed earth, though planks were sometimes used. Roofing materials varied, with thatch being the most common, though turf and even wooden shingles were also used.[195]

Stone was sometimes used to build churches. Bede makes it clear that the masonry construction of churches, including his own at Jarrow, was undertaken morem Romanorum, 'in the manner of the Romans,' in explicit contrast to existing traditions of timber construction. Even at Canterbury, Bede believed that St Augustine's first cathedral had been 'repaired' or 'recovered' (recuperavit) from an existing Roman church, when in fact it had been newly constructed from Roman materials. The belief was "the Christian Church was Roman therefore a masonry church was a Roman building".

The building of churches in Anglo-Saxon England essentially began with Augustine of Canterbury in Kent following 597; for this he probably imported workmen from Frankish Gaul. The cathedral and abbey in Canterbury, together with churches in Kent at Minster in Sheppey (c. 664) and Reculver (669), and in Essex at the Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall at Bradwell-on-Sea, define the earliest type in southeast England. A simple nave without aisles provided the setting for the main altar; east of this a chancel arch separated the apse for use by the clergy. Flanking the apse and east end of the nave were side chambers serving as sacristies; further porticus might continue along the nave to provide for burials and other purposes. In Northumbria the early development of Christianity was influenced by the Irish mission, important churches being built in timber. Masonry churches became prominent from the late 7th century with the foundations of Wilfrid at Ripon and Hexham, and of Benedict Biscop at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow. These buildings had long naves and small rectangular chancels; porticus sometimes surrounded the naves. Elaborate crypts are a feature of Wilfrid's buildings. The best preserved early Northumbrian church is Escomb Church.[196]

From the mid-8th century to the mid-10th century, several important buildings survive. One group comprises the first known churches utilizing aisles:

From the monastic revival of the second half of the tenth century, only a few documented buildings survive or have been excavated. Examples include the abbeys of Glastonbury; Old Minster, Winchester; Romsey; Cholsey; and Peterborough Cathedral. The majority of churches that have been described as Anglo-Saxon fall into the period between the late 10th century and the early 12th century. During this period, many settlements were first provided with stone churches, but timber also continued to be used; the best wood-framed church to survive is Greensted Church in Essex, no earlier than the 9th century, and no doubt typical of many parish churches. On the continent during the eleventh century, a group of interrelated Romanesque styles developed, associated with the rebuilding of many churches on a grand scale, made possible by a general advance in architectural technology and mason-craft.[196]

The first fully Romanesque church in England was Edward the Confessor's rebuilding of Westminster Abbey (c. 1042–60, now entirely lost to later construction), while the main development of the style only followed the Norman Conquest. However, at

-

Brixworth, Northants: monastery founded c. 690, one of the largest churches to survive relatively intact

Art

Early Anglo-Saxon art is seen mostly in decorated jewellery, like brooches, buckles, beads and wrist-clasps, some of outstanding quality. Characteristic of the 5th century is the

By the later 6th century, the best works from the south-east are distinguished by greater use of expensive materials, above all gold and garnets, reflecting the growing prosperity of a more organised society which had greater access to imported precious materials, as seen in the buckle from the

The Staffordshire Hoard is the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork yet found[update]. Discovered in a field near the village of Hammerwich, it consists of over 3,500 items[202] that are nearly all martial in character and contains no objects specific to female uses.[203][204] It demonstrates that considerable quantities of high-grade goldsmiths' work were in circulation among the elite during the 7th century. It also shows that the value of such items as currency and their potential roles as tribute or the spoils of war could, in a warrior society, outweigh appreciation of their integrity and artistry.[180]

The Christianization of the society revolutionised the visual arts, as well as other aspects of society. Art had to fulfil new functions, and whereas pagan art was abstract, Christianity required images clearly representing subjects. The transition between the Christian and pagan traditions is occasionally apparent in 7th century works; examples include the Crundale buckle[200] and the Canterbury pendant.[205] In addition to fostering metalworking skills, Christianity stimulated stone sculpture and manuscript illumination. In these Germanic motifs, such as interlace and animal ornament along with Celtic spiral patterns, are juxtaposed with Christian imagery and Mediterranean decoration, notably vine-scroll. The Ruthwell Cross, Bewcastle Cross and Easby Cross are leading Northumbrian examples of the Anglo-Saxon version of the Celtic high cross, generally with a slimmer shaft.

The jamb of the doorway at

Lindisfarne was an important centre of book production, along with

In the 8th century, Anglo-Saxon Christian art flourished with grand decorated manuscripts and sculptures, along with secular works which bear comparable ornament, like the Witham pins and the

There was demonstrable continuity in the south, even though the Danish settlement represented a watershed in England's artistic tradition. Wars and pillaging removed or destroyed much Anglo-Saxon art, while the settlement introduced new Scandinavian craftsmen and patrons. The result was to accentuate the pre-existing distinction between the art of the north and that of the south.[214] In the 10th and 11th centuries, the Viking dominated areas were characterised by stone sculpture in which the Anglo-Saxon tradition of cross shafts took on new forms, and a distinctive Anglo-Scandinavian monument, the 'hogback' tomb, was produced.[215] The decorative motifs used on these northern carvings (as on items of personal adornment or everyday use) echo Scandinavian styles. The Wessexan hegemony and the monastic reform movement appear to have been the catalysts for the rebirth of art in southern England from the end of the 9th century. Here artists responded primarily to continental art; foliage supplanting interlace as the preferred decorative motif. Key early works are the Alfred Jewel, which has fleshy leaves engraved on the back plate; and the stole and maniples of Bishop Frithestan of Winchester, which are ornamented with acanthus leaves, alongside figures that bear the stamp of Byzantine art. The surviving evidence points to Winchester and Canterbury as the leading centres of manuscript art in the second half of the 10th century: they developed colourful paintings with lavish foliate borders, and coloured line drawings.

By the early 11th century, these two traditions had fused and had spread to other centres. Although manuscripts dominate the corpus, sufficient architectural sculpture, ivory carving and metalwork survives to show that the same styles were current in secular art and became widespread in the south at parochial level. The wealth of England in the later tenth and eleventh century is clearly reflected in the lavish use of gold in manuscript art as well as for vessels, textiles and statues (now known only from descriptions). Widely admired, southern English art was highly influential in Normandy, France and Flanders from c. 1000.[216] Indeed, keen to possess it or recover its materials, the Normans appropriated it in large quantities in the wake of the Conquest. The Bayeux Tapestry, probably designed by a Canterbury artist for Bishop Odo of Bayeux, is arguably the apex of Anglo-Saxon art. Surveying nearly 600 years of continuous change, three common strands stand out: lavish colour and rich materials; an interplay between abstract ornament and representational subject matter; and a fusion of art styles reflecting English links to other parts of Europe.[217]

-

Codex Aureus of Canterburyc. 750

-

St Oswald's Priory Cross c. 890

Language

Old English (Ænglisċ, Anglisċ, Englisċ) is the earliest form of the English language. It was brought to Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers, and was spoken and written in parts of what are now England and southeastern Scotland until the mid-12th century, by which time it had evolved into Middle English. Old English was a West Germanic language, closely related to Old Frisian and Old Saxon (Old Low German). The language was fully inflected, with five grammatical cases, three grammatical numbers and three grammatical genders. Over time, Old English developed into four major dialects: Northumbrian, spoken north of the Humber; Mercian, spoken in the Midlands; Kentish, spoken in Kent; and West Saxon, spoken across the south and southwest. All of these dialects have direct descendants in modern England. Standard English developed from the Mercian dialect, as it was predominant in London.[218]

It is generally held that Old English received little influence from the Common Brittonic and British Latin spoken in southern Britain prior to the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, as it took in very few loan words from these languages. Though some scholars have claimed that Brittonic could have exerted an influence on English syntax and grammar,[219][220][221] these ideas have not become consensus views,[222] and have been criticized by other historical linguists.[223][224] Richard Coates has concluded that the strongest candidates for substratal Brittonic features in English are grammatical elements occurring in regional dialects in the north and west of England, such as the Northern Subject Rule.[225]

Old English was more clearly influenced by

Kinship

Local and extended kin groups were a key aspect of Anglo-Saxon culture. Kinship fueled societal advantages, freedom and the relationships to an elite, that allowed the Anglo-Saxons' culture and language to flourish.[4] The ties of loyalty to a lord were to the person of a lord and not to his station; there was no real concept of patriotism or loyalty to a cause. This explains why dynasties waxed and waned so quickly, since a kingdom was only as strong as its leader-king. There was no underlying administration or bureaucracy to maintain any gains beyond the lifetime of a leader. An example of this was the leadership of Rædwald of East Anglia and how the East Anglian primacy did not survive his death.[230] Kings could not make new laws barring exceptional circumstances. Their role instead was to uphold and clarify previous custom and to assure his subjects that he would uphold their ancient privileges, laws, and customs. Although the person of the king as a leader could be exalted, the office of kingship was not in any sense as powerful or as invested with authority as it was to become. One of the tools kings used was to tie themselves closely to the new Christian church, through the practice of having a church leader anoint and crown the king; God and king were then joined in peoples' minds.[231]

The ties of kinship meant that the relatives of a murdered person were obliged to exact vengeance for his or her death. This led to bloody and extensive feuds. As a way out of this deadly and futile custom the system of weregilds was instituted. The weregild set a monetary value on each person's life according to their wealth and social status. This value could also be used to set the fine payable if a person was injured or offended against. Robbing a thane called for a higher penalty than robbing a ceorl. On the other hand, a thane who thieved could pay a higher fine than a ceorl who did likewise. Men were willing to die for the lord and to support their comitatus (their warrior band). Evidence of this behavior (though it may be more a literary ideal than an actual social practice) can be observed in the story, made famous in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 755, of Cynewulf and Cyneheard, in which the followers of a defeated king decided to fight to the death rather than be reconciled after the death of their lord.[232]

This emphasis on social standing affected all parts of the Anglo-Saxon world. The courts, for example, did not attempt to discover the facts in a case; instead, in any dispute it was up to each party to get as many people as possible to swear to the rightness of their case, which became known as oath-swearing. The word of a thane counted for that of six ceorls.[233] It was assumed that any person of good character would be able to find enough people to swear to his innocence that his case would prosper.

Anglo-Saxon society was also decidedly patriarchal, but women were in some ways better off than they would be in later times. A woman could own property in her own right. She could and did rule a kingdom if her husband died. She could not be married without her consent, and any personal goods, including lands, that she brought into a marriage remained her own property. If she were injured or abused in her marriage, her relatives were expected to look after her interests.[234]

Law

The most noticeable feature of the Anglo-Saxon legal system is the apparent prevalence of legislation in the form of law codes. The early Anglo-Saxons were organised in various small kingdoms often corresponding to later shires or counties. The kings of these small kingdoms issued written laws, one of the earliest of which is attributed to Ethelbert, king of Kent, ca.560–616.[235] The Anglo-Saxon law codes follow a pattern found in mainland Europe where other groups of the former Roman Empire encountered government dependent upon written sources of law and hastened to display the claims of their own native traditions by reducing them to writing. These legal systems should not be thought of as operating like modern legislation, rather they are educational and political tools designed to demonstrate standards of good conduct rather than act as criteria for subsequent legal judgment.[236]

Although not themselves sources of law, Anglo-Saxon charters are a most valuable historical source for tracing the actual legal practices of the various Anglo-Saxon communities. A charter was a written document from a king or other authority confirming a grant either of land or some other valuable right. Their prevalence in the Anglo-Saxon state is a sign of sophistication. They were frequently appealed to and relied upon in litigation. Making grants and confirming those made by others was a major way in which Anglo-Saxon kings demonstrated their authority.[237]

The royal council or witan played a central but limited role in the Anglo-Saxon period. The main feature of the system was its high degree of decentralisation. The interference by the king through his granting of charters and the activity of his witan in litigation are exceptions rather than the rule in Anglo-Saxon times.[238] The most important court in the later Anglo-Saxon period was the shire court. Many shires (such as Kent and Sussex) were in the early days of the Anglo-Saxon settlement the centre of small independent kingdoms. As the kings first of Mercia and then of Wessex slowly extended their authority over the whole of England, they left the shire courts with overall responsibility for the administration of law.[239] The shire met in one or more traditional places, earlier in the open air and then later in a moot or meeting hall. The meeting of the shire court was presided over by an officer, the shire reeve or sheriff, whose appointment came in later Anglo-Saxon times into the hands of the king but had in earlier times been elective. The sheriff was not the judge of the court, merely its president. The judges of the court were all those who had the right and duty of attending the court, the suitors. These were originally all free male inhabitants of the neighbourhood, but over time suit of court became an obligation attached to particular holdings of land. The sessions of a shire court resembled more closely those of a modern local administrative body than a modern court. It could and did act judicially, but this was not its prime function. In the shire court, charters and writs would be read out for all to hear.[240]

Below the level of the shire, each county was divided into areas known as hundreds (or wapentakes in the north of England). These were originally groups of families rather than geographical areas. The hundred court was a smaller version of the shire court, presided over by the hundred bailiff, formerly a sheriff's appointment, but over the years many hundreds fell into the private hands of a local large landowner. Little is known about hundred court business, which was likely a mix of the administrative and judicial, but they remained in some areas an important forum for the settlement of local disputes well into the post-Conquest period.[241]

The Anglo-Saxon system put an emphasis upon compromise and arbitration: litigating parties were enjoined to settle their differences if possible. If they persisted in bringing a case for decision before a shire court, then it could be determined there. The suitors of the court would pronounce a judgment which fixed how the case would be decided: legal problems were considered to be too complex and difficult for mere human decision, and so proof or demonstration of the right would depend upon some irrational, non-human criterion. The normal methods of proof were oath-helping or the ordeal.[242] Oath-helping involved the party undergoing proof swearing to the truth of his claim or denial and having that oath reinforced by five or more others, chosen either by the party or by the court. The number of helpers required and the form of their oath differed from place to place and upon the nature of the dispute.[243] If either the party or any of the helpers failed in the oath, either refusing to take it or sometimes even making an error in the required formula, the proof failed and the case was adjudged to the other side. As "wager of law," it remained a way of determining cases in the common law until its abolition in the 19th century.[244]

The ordeal offered an alternative for those unable or unwilling to swear an oath. The two most common methods were the ordeal by hot iron and by cold water. The former consisted in carrying a red-hot iron for five paces: the wound was immediately bound up, and if on unbinding, it was found to be festering, the case was lost. In the ordeal by water, the victim, usually an accused person, was cast bound into water: if he sunk he was innocent, if he floated he was guilty. Although for perhaps understandable reasons, the ordeals became associated with trials in criminal matters. They were in essence tests of the truth of a claim or denial of a party and appropriate for trying any legal issue. The allocation of a mode of proof and who should bear it was the substance of the shire court's judgment.[242]

Literature

Old English literary works include genres such as

This literature is remarkable for being in the vernacular (Old English) in the early medieval period: almost all other written literature in Western Europe was in Latin at this time, but because of Alfred's programme of vernacular literacy, the oral traditions of Anglo-Saxon England ended up being converted into writing and preserved. Much of this preservation can be attributed to the monks of the tenth century, who made – at the very least – the copies of most of the literary manuscripts that still exist. Manuscripts were not common items. They were expensive and hard to make.

There are four great poetic codices of

Rather than being organized around rhyme, the poetic line in Anglo-Saxon is organised around alliteration, the repetition of stressed sounds; any repeated stressed sound, vowel or consonant, could be used. Anglo-Saxon lines are made up of two half-lines (in old-fashioned scholarship, these are called hemistiches) divided by a breath-pause or caesura. There must be at least one of the alliterating sounds on each side of the caesura.

hreran mid hondum hrimcealde sæ[i]