History of Filipino Americans

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| This article is part of a series on the | |

| History of the United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1981–1991 | |

| 1991–2008 | |

| Post-Cold War Era | 1991–2008 |

| 2008–present | |

| Modern Era | 2008–present |

The history of Filipino Americans begins in the 16th century when Filipinos first arrived in what is now the United States. The first Filipinos came to what is now the United States due to the Philippines being part of New Spain. Until the 19th century, the Philippines continued to be geographically isolated from the rest of New Spain in the Americas but maintained regular communication across the Pacific Ocean via the Manila galleon. Filipino seamen in the Americas settled in Louisiana, and Alta California, beginning in the 18th century. By the 19th century, Filipinos were living in the United States, fighting in the Battle of New Orleans and the American Civil War, with the first Filipino becoming a naturalized citizen of the United States before its end. In the final years of the 19th century, the United States went to war with Spain, ultimately annexing the Philippine Islands from Spain. Due to this, the history of the Philippines merged with that of the United States, beginning with the three-year-long Philippine–American War (1899–1902), which resulted in the defeat of the First Philippine Republic, and the attempted Americanization of the Philippines.

Mass migration of Filipinos to the United States began in the early 20th century due to Filipinos being U.S. nationals. These included Filipinos who enlisted as sailors of the United States Navy, pensionados, and laborers. During the Great Depression, Filipino Americans became targets of race-based violence, including race riots such as the one in Watsonville. The Philippine Independence Act was passed in 1934, redefining Filipinos as aliens for immigration; this encouraged Filipinos to return to the Philippines and established the Commonwealth of the Philippines. During World War II, the Philippines were occupied leading to resistance, the formation of segregated Filipino regiments, and the liberation of the islands.

After World War II, the Philippines gained independence in 1946. Benefits for most Filipino veterans were rescinded with the Rescission Act of 1946. Filipinos, primarily war brides, immigrated to the United States; further immigration was set to 100 persons a year due to the Luce–Celler Act of 1946, this though did not limit the number of Filipinos able to enlist into the United States Navy. In 1965, Filipino agricultural laborers, including Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, began the Delano grape strike. That same year the 100-person per year quota of Filipino immigrants was lifted, which began the current immigration wave; many of these immigrants were nurses. Filipino Americans began to become better integrated into American society, achieving many firsts. In 1992, the enlistment of Filipinos in the Philippines into the United States ended. By the early 21st century, Filipino American History Month was recognized.

Immigration history

Migration patterns of immigration of Filipinos to the U.S. have been recognized as occurring in four significant waves.

The second wave was during the period when the Philippines were a territory of the United States; as U.S. nationals, Filipinos were unrestricted from immigrating to the U.S. by the Immigration Act of 1917 that restricted other Asians.[1][8] This wave of immigration has been referred to as the manong generation.[9] Filipinos of this wave came for different reasons, but the majority were laborers, predominantly Ilocano and Visayans.[1] This wave of immigration was distinct from other Asian Americans, due to American influences, and education, in the Philippines; therefore they did not see themselves as aliens when they immigrated to the United States.[10] By 1920, the Filipino population in the mainland U.S. rose from nearly 400 to over 5,600. Then in 1930, the Filipino American population exceeded 45,000, including over 30,000 in California and 3,400 in Washington.[7] During the early 20th century, anti-miscegenation laws began to impact Filipino Americans attempting to marry non-Filipinos, with some able to legalize their unions, and others not; in 1933 California amended its laws to specify that Filipinos could not marry Whites.[11][12]

During the Great Depression, Filipino Americans were also affected, losing jobs, and being the target of race-based violence.[13] This wave of immigration ended due to the Philippine Independence Act in 1934, which restricted immigration to 50 persons a year.[1] Beginning in 1901, Filipinos were allowed to enlist in the U.S. Navy.[14] While serving, Filipino sailors would bring over their spouse from the Philippines, or marry a spouse in the U.S., parenting and raising children who would be part of a distinct Navy-related Filipino American immigrant community.[15][16] Before the end of World War I, Filipino sailors were allowed to serve in a number of ratings; however, due to a rules change during the interwar period, Filipino sailors were restricted to officers' stewards and mess attendants.[17] Filipinos who immigrated to the United States, due to their military service, were exempt to quota restrictions placed on Filipino immigration at the time.[18] This ended in 1946, following the independence of the Philippines from the U.S., but resumed in 1947 due to language inserted into the Military Base Agreement between the U.S. and the Republic of the Philippines.[14] In 1973, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt removed the restrictions on Filipino sailors, allowing them to enter any rate they qualified for;[19] in 1976 there were about 17,000 Filipinos serving in the U.S. Navy.[14] Navy based immigration of Philippine citizens stopped with the expiration of the Military Bases Agreement in 1992.[20]

The third wave of immigration followed the events of World War II.[21] Filipinos who had served in World War II were given the option of becoming U.S. citizens, and many took the opportunity,[22] over 10,000 according to Barkan.[23][24] Filipina war brides were allowed to immigrate to the U.S. due to the War Brides Act and Alien Fiancées and Fiancés Act, with approximately 16,000 Filipinas entering the U.S. in the years following the war.[21][25] This immigration was not limited to Filipinas and children; between 1946 and 1950, one Filipino groom was granted immigration under the War Brides Act.[26] A source of immigration was opened up with the Luce–Celler Act, that gave the Philippines a quota of 100 persons a year; yet records show that 32,201 Filipinos immigrated between 1953 and 1965.[27] The laws prevented interracial marriage with Filipinos continued until 1948 in California;[11] this extended nationally in 1967 when anti-miscegenation laws were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court by Loving v. Virginia.[28] This wave ended in 1965.[1]

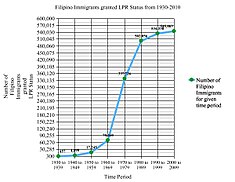

The fourth and present wave of immigration began in 1965 with the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. It ended national quotas, and provided an unlimited number of visas for family reunification.[1] By the 1970s and 1980s, the immigration of Filipina wives of service members reached annual rates of five to eight thousand.[29] The Philippines became the largest source of legal immigration to the U.S. from Asia.[18] Many Filipinas of this new wave of migration have migrated here as professionals due to a shortage in qualified nurses;[30] from 1966 until 1991, at least 35,000 Filipino nurses immigrated to the U.S.[15] As of 2005[update], 55% of foreign-trained registered nurses taking the qualifying exam administered by the Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools (CGFNS) were educated in the Philippines.[31] Although Filipinos made up 24 percent of foreign physicians entering the U.S. in 1970, Filipino physicians experienced widespread underemployment in the 1970s due to the requirement of passing the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) exam to practice in the U.S.[32]Immigrants experience a culture shock once arriving to the new country, in which adapting skills are necessary to survive in society. Although, with the past English education taught in the Philippines, many Filipinos are already educated in English and can efficiently talk fluently.[33]

In 2016, 50,609 Filipinos obtained their lawful permanent residency, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.[34] Of those Filipinos receiving their lawful permanent residency status in 2016, 66% were new arrivals, while 34% were immigrants who adjusted their status within the U.S.[35] In 2016, data collected from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security found that the categories of admission for Filipino immigrants were composed mainly of immediate relatives, that is 57% of admissions.[35] This makes the admission of immediate relatives for Filipinos higher than the overall average lawful permanent resident immigrants, which is composed of only 47.9%.[36] Following immediate relative admission, family sponsored and employment-based admission make up the next highest means of entry for Philippine immigration, with 28% and 14% respectively.[35] Like immediate relative admission, both of these categories are higher than that of the overall U.S. lawful permanent resident immigrants. Diversity, refugees and asylum, and other categories of admission make up less than one percent of Filipino immigrants granted lawful permanent resident status in 2016.[35]

Timeline

- 1573–1811, Between roughly 1556 and 1813, Spain engaged in the galleon trade between Manila and Acapulco. The galleons were built in the shipyards of Cavite, outside Manila, by Filipino craftsmen. The trade was funded by Chinese traders, manned by Filipino sailors and "supervised" by Mexico City officials. During this time, Spain recruited Mexicans to serve as soldiers in Manila. Likewise, they drafted Filipinos to serve as soldiers in Mexico. Once drafted and posted to the Americas, Filipino soldiers were frequently not returned home.[37]

- 1587,

- 1595, Filipino were among the crew aboard the San Augustine when it wrecked near Point Reyes, California.[40]

- 1763, First permanent Filipino settlements established in North America near Barataria Bay in southern Louisiana.[41][4][42]

- 1769, Filipino sailors aboard the San Carlos die aboard ship in San Diego Bay during the Portolá expedition, and are buried ashore.[43]

- 1779, A Filipino mariner, of the San Jose received their confirmation at Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo;[44] the confirmation was conducted by Fr. Junípero Serra.[45]

- 1781, Antonio Miranda Rodriguez was chosen as a member of the first group of settlers to establish the City of Los Angeles, California. He and his daughter fell sick with smallpox while en route, and remained in Baja California for an extended period to recuperate. When they finally arrived in Alta California, it was realised that Miranda Rodriguez was a skilled gunsmith and he was reassigned in 1782 to the Presidio of Santa Barbara as an armorer.[46][47] When he died, he was buried at the presidio's chapel.[48]

- 1796, The first American trading ship reaches Manila, the Astrea, under the command of Captain Henry Prince.[49]

- 1814, During the War of 1812, Filipinos residing in Louisiana, referred to as "Manilamen" residing near the city of New Orleans, including the Manila Village, were among the "Baratarians", a group of men who fought with Jean Lafitte and Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. The battle was fought after the Treaty of Ghent was signed.[50][51]

- 1861–1865, Approximately 100 Filipinos and Chinese enlist during the American Civil War into the Union Army and Navy, as well as serving, in smaller numbers, in the armed forces of the Confederate States of America.[52]

- 1870, Filipinos mestizos studying in New Orleans form the first Filipino Association in the United States, the "Sociedad de Beneficencia de los Hispanos Filipinos".[53]

- 1888, José Rizal arrives at the port of San Francisco for his trip through the United States.[44]

- 1898, on May 1, the United States Navy decisively defeated Spain in the Battle of Manila Bay, the first battle of the Spanish–American War, beginning the American Colonial Era in the Philippines.[54] On June 12, Filipino revolutionaries declare independence from Spain in Kawit, Cavite.[54] Prior to this year, Ramon Reyes Lala becomes the first naturalized Filipino American.[55]

- 1899, Philippine–American War begins.[54]

- 1901, United States Navy begins recruiting Filipinos.[56]

- 1902, Philippine–American War ends.[54][57] Philippine Bill of 1902 passed by the U.S. Congress.[58]

- 1903, First Pensionados, Filipinos invited to attend college in the United States on American government scholarships, arrive.[59]

- 1906, First Filipino laborers migrate to the United States to work on the Hawaiian sugarcane and pineapple plantations, California and Washington asparagus farms, Washington lumbercamps and Alaska salmon canneries.[8] About 200 Filipino "pensionados" are brought to the U.S. to get an American education.[60]

- 1907, Benito Legarda and Pablo Ocampo, become the first Resident Commissioners from the Philippines, in the United States House of Representatives.[61]

- 1910, First Filipino, Vicente Lim, attends West Point.[62][63]

- 1911, José B. Nísperos becomes the first Asian American to be awarded the Medal of Honor.[50][64] Nevada became the first state to include Filipinos, referring to them as "Malays", in their miscegenation law.[65]

- 1912, Filipino Association of Philadelphia (now known as Filipino American Association of Philadelphia, Inc., or FAAPI) is founded by Agripino Jaucian; it is perhaps the oldest Filipino organization in continuous existence in the United States. The name change came about to include the growing number of American wives.[66][67]

- 1913, Several months after the Battle of Bud Bagsak, armed resistance ended, finishing the Moro Rebellion.[68]

- 1915, Telesforo Trinidad becomes the only Asian American sailor, as of 2010[update], to earn the Medal of Honor.[69]

- 1917, Philippine National Guard mustered into federal service[70]

- 1919, USS Rizal is commissioned into the United States Navy.[71] On August 31 lawyer and community leader Pablo Manlapit organizes the Filipino Labor Federation to demand higher wages and better working conditions for sakadas.[72]

- 1920s, Filipino labor leaders organize unions and strategic strikes to improve working and living conditions.[73] Among the union organizers there were individuals who had harbored communist sentiments, as well as those who were nationalistic and anti-communist.[74]

- 1924, during a labor strike in Hawaii, as a result of violence by Visayans strikers against Ilocano non-strikers, 16 strikers and four law enforcement officials were killed during the Hanapepe massacre.[75]

- 1927, Anti-Filipino riots occur in the Yakima Valley, Washington.[76][77]

- 1928, Filipino Businessman Pedro Flores opens Flores yo-yos, which is credited with starting the yo-yo craze in the United States. He came up with and copyrighted the word "yo-yo".[78] He also applied for and received a trademark for the Flores Yo-yo, which was registered on July 22, 1930.[78] His company went on to become the foundation of the later Duncan yo-yo company.[78] Anti-Filipino riots occur in the Wenatchee Valley.[76][79]

- 1929, An anti-Filipino riot occurs in Exeter, California.[77]

- 1930, Anti-Filipino riots break out in Watsonville and other California rural communities, in part because of Filipino men having intimate relations with white women, which was in violation of the California anti-miscegenation laws of the time.[77][80] The Filipino Federation of America building in Stockton was bombed.[81] A Filipino labor camp was bombed in the Imperial Valley.[82]

- 1933, After the Supreme Court of California found in Roldan v. Los Angeles County that existing laws against marriage between white persons and "Mongoloids" did not bar a Filipino man from marrying a white woman,[83] California's anti-miscegenation law, Civil Code Section 60 was amended to prohibit marriages between white persons and members of the "Malay race" (e.g. Filipinos).[84]

- 1934, The Tydings–McDuffie Act, known as the Philippine Independence Act, limited Filipino immigration to the U.S. to 50 persons a year (not to apply to persons coming or seeking to come to the Territory of Hawaii);[85] A Filipino Labor Union Incorporated camp was attacked in Salinas after a failed strike.[86]

- 1935, Philippines becomes self-governing with the Commonwealth of the Philippines inaugurated.[87]

- 1936, Fe del Mundo continues her education at Harvard Medical School.[88]

- 1941, Washington Supreme Court rules unconstitutional the Anti-Alien Land Law of 1937 which banned Filipino Americans from owning land.[89][90]

- Early 1942, Filipinos communities in the United States began to designate themselves as Filipinos to avoid anti-Japanese discrimination[91][92]

- April 1942, First and Second Filipino Regiments formed in the U.S. composed of Filipino agricultural workers.[22][93]

- May 1942, After the fall of Bataan and Coregidor to the Japanese, the U.S. Congress passes a law which grants U.S. citizenship to Filipinos and other aliens who served under the U.S. Armed Forces.[94]

- 1946, Rescission Act of 1946, taking away the veterans benefits pledged to Filipino service members during world War II.[95] Only four thousand service members were able to gain citizenship during this period.[94][96] The United States recognizes Philippine Independence through the Treaty of Manila.[97] America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan published.[98] Filipino Naturalization Act allows naturalization of Filipino Americans,[99] granted citizenship to those who arrived prior to March 1943.[100]

- 1948, Vicki Draves wins two Olympic gold medals; as of 2010[update] is the only Filipino to have won a gold medal.[101] California Supreme Court rules California's anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional in the case of Perez v. Sharp,[102] ending racially based prohibitions on marriage in the state (although it wasn't until Loving v. Virginia in 1967 that interracial marriages were legalized nationwide). Celestino Alfafara wins California Supreme Court decision allowing aliens the right to own property.[103]

- 1955, Peter Aduja becomes first Filipino American elected to office as a member of the Hawaii Territorial House of Representatives.[104]

- 1956, Bobby Balcena becomes first Asian American to play Major League baseball, playing for the Cincinnati Reds.[105]

- 1965, Congress passes the Immigration and Nationality Act which facilitates entry for skilled Filipino workers.[106] Delano grape strike begins when members of Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee led by Philip Vera Cruz, Larry Dulay Itliong, Benjamin Gines, Andy Imutan and Pete Velasco with mostly Filipino farm workers.[107] The last Filipino village, Manila Village, in the Louisiana Bayou is destroyed by Hurricane Betsy.[42][108]

- 1967, The Philippine (now Pilipino) American Collegiate Endeavor (PACE) founded at San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University).[109][110]

- 1969, Filipino Students Association (FSA) founded by Filipino American students at University of California, Berkeley during the Third World Movement; later renamed the Pilipino American Alliance.[111] Dr. Antonio Ragadio, President of the Filipino Dental Association of Northern California, and Estrella Salaver, President and Founder of the Philippine American Cultural Foundation, work with Assemblyman Willie Brown and Senator Milton Marks to pass bill allowing Filipino and other foreign dentists to take the California qualifying examinations to practice in California.[112]

- 1972, United States Coast Guard discontinued its program to enlist Filipinos from the Philippines.[113]

- 1973, Larry Asera becomes the first Filipino American elected in the Continental United States, being elected to the city council of Vallejo.[114]

- 1974, Benjamin Menor appointed first Filipino American in a state's highest judiciary office as Justice of the Hawaii State Supreme Court.[115] Thelma Buchholdt is the first Filipino American, and first Asian American, woman elected to a state legislature in the United States, in the Alaska House of Representatives.[116][117]

- 1975, Kauai's Eduardo Malapit elected first Filipino American mayor in the United States.[118]

- 1977, Evictions are carried out of elderly Filipinos from the International Hotel in Manilatown, San Francisco, effectively ending the community.[119]

- 1978, Alfred Laureta becomes the first Filipino American federal judge, serving on the District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands.[117][120]

- 1981, Filipino American labor activists Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes are both assassinated June 1, 1981, inside a Seattle downtown union hall.[121] International Hotel in Manilatown, San Francisco is demolished.[122]

- 1983, California Governor Jerry Brown appoints Ronald Quidachay as first Filipino-American judge to the San Francisco Municipal Court.[123]

- 1990, David Mercado Valderrama becomes first Filipino American elected to a state legislature in the Continental United States, serving Prince George's County in Maryland.[124][125] Immigration reform Act of 1990 is passed by the U.S. Congress granting U.S. citizenship to Filipino World War II veterans;[126] more than 20,000 veterans naturalized due to the act.[127]

- 1992, Velma Veloria becomes first Asian American elected to the Washington State Legislature.[128] Bobby Scott becomes the first person with Filipino heritage elected to the United States House of Representatives.[124][129][130] Eleanor Mariano becomes the first female Physician to the President; later Mariano becomes the first female director of the White House Medical Unit (1994), and the first Filipino American flag officer (2000).[50][131] The United States Navy ends its program to enlist Filipinos from the Philippines, due to the end of the Military Base Agreement.[132]

- 1994, Benjamin J. Cayetano becomes the first Filipino American governor in the United States.[133]

- 1995, The nation's largest Filipino mural, Gintong Kasaysayan, Gintong Pamana (Filipino Americans: A Glorious History, A Golden Legacy) in Los Angeles is unveiled and dedicated with over 600 people attending.[134] Edward Soriano becomes the first Filipino American general officer.[135]

- 1999, U.S. postal worker Joseph Ileto was murdered in a hate crime in Chatsworth, California, and whose death is often overlooked outside of the Filipino American community.[136] The Carlos Bulosan Memorial Exhibit opens in Seattle's Eastern Hotel in the International District, honoring the Filipino novelist and poet Carlos Bulosan.[137] A street on Fort Sam Houston is named after Medal of Honor recipient Jose Calugas.[138]

- 2000, Robert Bunda elected Hawaii Senate President, the First Filipino American to hold the position.[139] Angela Perez Baraquio becomes first Filipino American crowned as Miss America.[139] John Ensign, who has a Filipino great-grandparent, is elected to the United States Senate.[129][140]

- 2002, in April, the Bataan Death March Memorial, is dedicated in Las Cruces, New Mexico; it is the first, and only, federally funded memorial for the Bataan Death March.[141][142] In August, Historic Filipinotown is designated by Los Angeles[143]

- 2003, Philippine Republic Act No. 9225, also known as the Citizenship Retention and Re-Acquisition Act of 2003 enacted, allowing natural-born Filipinos naturalized in the United States and their unmarried minor children to reclaim Filipino nationality and hold dual citizenship.[144][145]

- 2005, Hurricane Katrina impacts New Orleans, damaging or destroying the work of Marina Espina, research of Filipino history in New Orleans dating back to the 18th century; it also displaced many Filipino American families that lived in the area for over 7 generations.[146]

- 2006, first monument dedicated to Filipino soldiers who fought for the United States in World War II unveiled in Historic Filipinotown, Los Angeles, California.[147] A portion of California State Route 54 is named the Filipino-American Highway.[148][149] Congress passes legislation that commemorates 100 Years of Filipino Migration to the United States.[150] Hawaii celebrates the centennial of Filipinos in Hawaii.[151]

- 2007, First American public park built with Filipino themed design features unveiled in LA's Historic Filipinotown.[152]

- 2008, Bruce Reyes-Chow, 3rd generation Filipino and Chinese American was Elected Moderator of Presbyterian Church (USA).[153]

- 2009, Filipino American History Month is recognized in California.[154] Steve Austria becomes "the first, first-generation Filipino to be elected to the United States Congress."[129][155] Mona Pasquil becomes first Filipino American, and first Asian American, lieutenant governor of California.[156]

- 2011, Amado Gabriel Esteban becomes the first Filipino American president of a university, Seton Hall University, in the United States.[157]

- 2012, Lorna G. Schofield becomes a Filipino American federal judge.[158] Rob Bonta, becomes the first Filipino American elected to the California State Legislature.[159]

- 2013, California passed legislation that required that Filipino contributions to the state's history be included in the curriculum.[160]

- 2014, an overpass on the Filipino-American Highway is named Itliong-Vera Cruz Memorial Bridge,[148][161] named for two prominent Filipino American leaders of the Delano Grape Strike, Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz[162]

- 2015, Ralph Deleon, who was later highlighted in a 2016 speech about immigration by then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, is convicted of provide material support to terrorists.[163] Itliong-Vera Cruz Middle School, in Union City, California becomes the first school in the United States named for a Filipino American.[162][164]

- 2017, Oscar A. Solis becomes the first Filipino American Catholic diocesan bishop in the United States;[165] he was elevated to a bishop in Los Angeles in 2004, being the first Filipino American bishop.[166]

- 2018, Academy, Emmy, Grammy, and Tony Awards winner (EGOT).[168]

- 2019, Darren Criss becomes the first Filipino American to win a Golden Globe.[169]

- 2020, Dozens of Filipino American healthcare workers have died due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the New Jersey-New York area,[170] and elsewhere.[171] Of all nurses who died with a COVID-19 infection nationally in 2020, almost a third were Filipino Americans.[172]

See also

- History of Asian Americans

- Filipino American history in San Diego

- Filipino American military history in World War II

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4129-0948-8. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-118-01977-1.

- ISBN 978-1-59884-219-7.

- ^ a b Welch, Michael Patrick (October 27, 2014). "NOLA Filipino History Stretches for Centuries". New Orleans & Me. The Arts Council of New Orleans. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ^ Eloisa Gomez Borah (1997). "Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1989" (PDF). Anderson School of Management. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- ^ "Ramon Reyes Lala". Los Angeles Herald. September 11, 1898. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

Everybody's Magazine. North American Company. 1900. pp. 381–388.

The American Magazine. Crowell-Collier Publishing Company. 1900. p. 97.

Josephus Nelson Larned; Philip Patterson Wells (1902). The Literature of American History: A Bibliographical Guide, in which the Scope, Character, and Comparative Worth of Books in Selected Lists are Set Forth in Brief Notes by Critics of Authority. American Library Association. p. 272.

Gomez, Buddy (March 30, 2018). "OPINION: The first naturalized Filipino-American". ABS CBN News. Philippines. Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018. - ^ a b Takaki 1998, p. 315.

- ^ JSTOR 3002046.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-0948-8. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

Included in this group were Pensionados, Sakadas, Alaskeros, and Manongs primarily from the Illocos and Visayas regions.

- ISBN 978-0-19-515377-4. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

They were, however, officially under the protection of the United States, which governed the Philippines, and herein they took a distinctive characteristics. First of all, they had been inculcated in the Philippines, through the American-sponsored education system and through the general point of view of a colonial society strongly under American influence, in the belief that all men were created equal, in fact and under the law, and that included them. Second, they spoke English, excellently in many cases, thanks once again to the American sponsored educational system in the Philippines. Filipino migrant workers did not see themselves as aliens.

- ^ ISBN 9780814709214.

- ^ Volpp, Leti (1999–2000). "American Mestizo: Filipinos andAntimiscegenation Laws in California" (PDF). U.C. Davis Law Review. 33: 795–835. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-0646-6. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

Filipinos immigrants urban.

- ^ a b c Hooker, J.S. (July 7, 2006). "Filipinos in the United States Navy". Navy Department Library. United States Navy. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-986047-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8135-5326-9.

- ISBN 9780520235274. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Espiritu, Yen Le; Wolf, Diane L. (1999). "The Paradox of Assimilation: Children of Filipino Immigrants in San Diego -- Yen Espiritu". Research & Seminars. University of California, Davis. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ Ramon J. Farolan (July 21, 2003). "From Stewards to Admirals: Filipinos in the U.S. Navy". Asian Journal. Archived from the original on March 24, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ MC3 Rialyn Rodrigo (March 1, 2009). "Philippine Enlistment Program Sailors Reflect on Heritage". Navy News Service. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ PMID 12282604.

- ^ a b "California's Filipino Infantry". The California State Military Museum. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-313-29742-7. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

Leyte 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment.

- JSTOR 27500294.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-9109-7. Archivedfrom the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-931112-99-4. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-231-12082-1. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ Martyn, Byron Curti (June 1979). Racism in the United States: A history of the anti-miscegenation legislation and litigation (Dissertation). University of Southern California. pp. 1260–1261. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-0556-5. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- .

- ^ "Philippine Nurses in the U.S.—Yesterday and Today". Minority Nurse. Springer. March 30, 2013. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ Takaki 1998, pp. 434–436.

- ISSN 0739-3148.

- ^ "Legal Permanent Residents (LPRs): Philippines". Department of Homeland Security. July 29, 2015. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Yearbook 2016". Department of Homeland Security. May 16, 2017. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ Kandel, William A. (February 9, 2018). "U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Peterson, Andrew (Spring 2011). "What Really Made the World go Around?: Indio Contributions to the Acapulco-Manila Galleon Trade" (PDF). Explorations. 11 (1): 3–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2018.

Sionil Jose, F.; Mercene, Floro L.; Quiazon, Serafin D. (June 3, 2007). "Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the 16th century". Asian Journal. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018. - ^ "Historic Site, During the Manila". Michael L. Baird. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

Eloisa Gomez Borah (1997). "Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1989" (PDF). Anderson School of Management. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

Contreras, Shirley (November 6, 2016). "Marking Filipino-American history on Central Coast". Santa Maria Times. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. - ISBN 978-0-679-74072-8.

- ISBN 978-0-307-79526-7.on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

Sobredo, James (July 1999). "Filipino Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area, Stockton, and Seattle". Asian American Studies. California State University, Sacramento. Archived from the original - ISBN 978-971-542-529-2.

- ^ a b Westbrook, Laura (2008). "Mabuhay Pilipino! (Long Life!): Filipino Culture in Southeast Louisiana". Louisiana Folklife Program. Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-317-13365-0.. T.Y. Crowell. p. 65.

Once the San Carlos reached San Diego, Vila recorded by names and dates the deaths of three additional crewmen: Fernandez de Medina, Philpppine seaman (died 5 May); Manuel Sanchez, cabin Boy (died 10 May); and Matheo Francisco, Philippine seaman (died 10 May). These three presumably were buried ashore at San Diego.

Pourade, Richard F. (1960). "Expeditions by Sea". The History of San Diego: v.1 The Explorers, 1492-1774. San Diego: Copley Newspapers.

Rolle, Andrew F. (1969). California: A History - ^ ISBN 978-0-8147-3297-7.

- ISBN 978-971-542-529-2.

- ^ "Original Settlers (Pobladores) of El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles, 1781". laalmanac.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

"Art exhibit on arrival of first Filipino in Los Angeles opens". Philippine Daily Inquirer. May 10, 2014. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018. - ISBN 978-1-4381-0711-0.

- ^ Acena, Albert A. (Summer 2008). ""Invisible Minority" No More: Filipino Americans in San Mateo County" (PDF). La Peninsula. XXXVII (1): 3–41. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-61423-790-7.

- ^ a b c "Asian American and Pacific Islander Fact Sheet" (PDF). Center for Minority Veterans. United States Department of Veterans Affairs. March 17, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ISBN 978-971-542-529-2.(PDF) (Report). Corps of Engineers, New Orleans District. p. 294. Southeast/Southwest Team. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation (1977). Jean Lafitte National Park: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, United States Senate, Ninety-fourth Congress, Second Session, on S. 3546 ... December 6, 1976. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 80–81.

Hinton, Matthew (October 23, 2019). "From raised houses to dried shrimp recipes, Filipinos have made lasting effects on the local culture". Very Local New Orleans. Hearst Television Inc. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

Greene, Jerome A.; Clemenson, A Berle; Paige, John C.; Stuart, David R.; Van Horn, Lawrence F. (May 1984). Mississippi River Cultural Resources Survey, A Comprehensive Study, Phase I, Component A: Thematic historical overview - ISBN 978-971-542-529-2.(PDF) from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

Foenander, Terry; Milligan, Edward (March 2015). "Asian and Pacific Islanders in the Civil War" (PDF). The Civil War. National Park Service. Archived - ISBN 978-0-19-022118-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7006-0990-1.

- ^ "Ramon Reyes Lala, Only Filipino in America". Los Angeles Herald. September 11, 1898. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection, University of California, Riverside.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-7535-6.. Compilation of navy: annotated. [Letters from the acting secretary of the navy transmitting pursuant to Senate resolution no. 262, Sixty-third Congress, a compilation of laws relating to the navy, Navy department, and Marine corps, in force March 4, 1921, with annotations, showing how such laws have been construed and applied by the Navy department, the comptroller of the Treasury, the attorney general, or the courts ... ]. Govt. print. off. p. 856.

United States; United States. Judge-advocate-general's dept. (Navy); United States. Navy. Office of the Judge Advocate General (1922). "General Order No. 40" - ^ Fisher, Max (July 4, 2012). "The One Other Country That Celebrates the Fourth of July (Sort Of)". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

Though American forces effectively defeated the Filipinos in April 1902, President Teddy Roosevelt waited until July 4, 1902, to declare victory.

- ^ United States (1914). Compiled Statutes of the United States, 1913: Embracing the Statutes of the United States of a General and Permanent Nature in Force December 31, 1913, Incorporating Under the Headings of the Revised Statutes the Subsequent Laws, Together with Explanatory and Historical Notes. West publishing Company. pp. 1529–1563.

"Chronology for the Philippine Islands and Guam in the Spanish–American War". The World of 1898: The Spanish–American War. United States: Library of Congress. June 22, 2011. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018. - ISBN 978-0-230-60011-9. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- (14 December 2005)

- ISBN 978-1-4798-3851-6.. Bureau of printing. p. 95.

Philippines. Legislature. Philippine Commission; William Howard Taft (1908). Journal of the Philippine commission: being the inaugural session of the first Philippine Legislature, begun and held at the city of Manila October 16, 1907 [to February 1, 1908] - ^ Annual report of the Secretary of War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1915. p. 11. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ Marc Lawrence. "Filipino Martial Arts in the United States" (PDF). South Bay Filipino Martial Arts Club. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

In 1910 the U.S. began sending one outstanding Filipino soldier per year to West Point, and by 1941 some of these men had risen to the rank of senior officers.

- ISBN 978-0-8103-9193-2. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-19-509463-3.

- ^ "Filipino American Association of Philadelphia, Inc". Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Filipino-American Association of Philadelphia Inc". Asian Journal. February 1, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

The organization drafted its constitution and by-laws and became charted in the city of Philadelphia and incorporated in the State of Pennsylvania in 1917. FAAPI is the oldest ongoing organization of Filipinos and Filipino-Americans in the Delaware Valley and perhaps in the U.S.

- ^ Miller, Daniel G. (2009). American Military Strategy During the Moro Insurrection in the Philippines 1903-1913 (PDF) (thesis for Master of Military Art and Science). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-317-47645-0.from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

"Telesforo Trinidad". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. February 20, 2015. Archived - New York Times. December 7, 1921. p. 1.

- ISBN 978-0-8078-2985-1.from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

Akers, Regina T. (April 2017). "Asian Americans in the U.S. Military with an emphasis on the U.S. Navy". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. Archived - ISBN 978-0944081044. Archivedfrom the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- . Mona Palmer. 1920. p. 166.

- ^ A. F. Hinriehs (1945). Labor Unionism in American Agriculture (Report). United States Department of Labor. p. 129. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018 – via Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-0890-7.

- ^ a b "IV. Timeline: Asian Americans in Washington State History". Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7425-4651-6. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c Lucky Meisenheimer, MD. "Pedro Flores". nationalyoyo.org. Archived from the original on December 19, 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-405-09508-5. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-19-991062-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7385-5624-6.

- ISBN 978-0-8135-5326-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-0556-5

- JSTOR 3476961., citing Cal. Stats. 1933, p. 561.from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

Association of American Law Schools (1950). Selected essays on family law. Foundation Press. pp. 279. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2016.The second disttinct change came in 1933 when the word "Malay" was added to the prohibited class,. Cal. Stats. 1933, p. 561.

University of California, Berkeley. School of Law; University of California, Berkeley School of Jurisprudence (1944). California law review. School of Jurisprudence of the University of California. pp. 272. ArchivedAll marriages of white persons with Negros, Mongolians, members of the Malay race, of mulattos are illegal and void.

- ^ "The Philippine Independence Act (Tydings-McDuffie Act)". Chanrobles Law Library. March 24, 1934. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ^ A. F. Hinriehs (1945). Labor Unionism in American Agriculture (Report). United States Department of Labor. pp. 129–130. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018 – via Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

"Salinas Scene of Race Riots with Filipinos: None Hurt as Angry Crowd Routs Islanders". Healdsburg Tribune. United Press. September 22, 1934. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection, University of California, Riverside. - ISBN 978-3-643-80169-2.

- ISBN 978-0-399-57887-8.

- ^ "Filipino Americans". Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ^ Mark L. Lazarus III. "An Historical Analysis of Alien Land Law: Washington Territory & State 1853–1889". Seattle University School of Law. Seattle University. Archived from ""washington+supreme+Court"+unconstitutional+Filipino+"Alien+Land+Law"" the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

Finally, the only other reported case on alien land rights went before the Washington Supreme Court in early 1941. The court held that a 1937 amendment to the alien land law was unconstitutional inasmuch as it might disable citizens of the Philippines.30'

- ISBN 978-1-56639-096-5. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-316-83130-7. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

Liz Megino recalled how Filipinos had to distinguish themselves from Japanese shortly after the beginning of the war: "My mother told me to make sure you say you're not Japanese if they ask you who you are. Filipinos wore buttons saying, 'I am Filipino'."

- ^ "An Untold Triumph". Asian American Studies. California State University, Sacramento. Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

Facing discrimination and hard times here in California and all along the west coast, thousands of Filipinos worked in agricultural fields, in the service industry, and in other low paying jobs. The war provided the opportunity for Filipinos to fight for the United States and prove their loyalty as Americans.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-56639-317-1. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- doi:10.15779/Z38129V. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Rodis, Rodel (February 19, 2016). "70th anniversary of the infamous Rescission Act of 1946". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Guillermo, Emil (February 18, 2016). "Forgotten: The Battle Thousands of WWII Veterans Are Still Fighting". NBC News. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Conclara, Rommel (February 22, 2016). "Fight for Filvets' benefits continues on 70th anniversary of Rescission Act". ABS CBN News. Archived - ^ "8 FAM 302.5 Special Citizenship Provisions Regarding the Philippines". Foreign Affairs Manual and Handbook. United States Department of State. May 15, 2020. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

Not until August, 1946, did the INS designate a new section 702 official for the Philippines, who naturalized approximately 4,000 Filipinos before the December 31, 1946, expiration date of the 1940 act.

- ^ "Treaty of General Relations Between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines. Signed at Manila, on 4 July 1946" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ^ "Author, Poet, and Worker: The World of Carlos Bulosan". Digital Collections. University of Washington. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-56639-779-7. Archivedfrom the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ "20th Century – Post WWII". Asian American Studies. Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on October 30, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

Filipino Naturalization Act grants US citizenship to filipinos who had arrived before March 24, 1943.

- ^ Cabanilla, Devin Israel (December 15, 2016). "Media fail to give REAL first Asian American Olympic gold medalist her due". The Seattle Globalist. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

Guillermo, Emil (October 9, 2015). "First Asian-American Woman to Win Olympic Gold Medal Gets New Recognition". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

McLellan, Dennis (April 29, 2010). "Victoria Manalo Draves dies at 85; Olympic gold medal diver". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

Light, Claire (March 14, 2010). "Women's History Month Profile: Victoria Manalo Draves". Hyphen. Asian Americans for Civil Rights and Equality. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

Rodis, Rodel (October 16, 2015). "The Olympic triumph of Vicki Manalo Draves". Philippine Daily Inquirer. La Paz, Makati City, Philippines. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.Victoria Manalo Draves, or Vicki as she liked to be called, made history as the first American woman to win two gold medals for diving and as the first, and still only Filipino, to win an Olympic gold medal and she won two of them in springboard and platform diving at the 1948 Olympics in London.

- ^ "Perez vs. Sharp – End to Miscegenation Laws in California". Los Angeles Almanac. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-4651-6. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Borreca, Richard (February 22, 2007). "Lawmaker first U.S. Filipino to hold office: Peter Aduja / 1920-2007". Honolulu Star Bulletin. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-3291-2.

- ISBN 978-0-313-29742-7.

- ^ Filipino Memorial Project (April 25, 2011). Remembering the Leadership of Filipino Farmworkers in the 1965 Delano Grape Strike: A Memorial to their Dedication and Legacy (PDF) (Report). City of Milpitas. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Galila, Wilfred (November 16, 2017). "Children's book on Fil-Am labor hero Larry Itliong is in the works". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

"Historical society pans 'Cesar Chavez' film for inaccuracies". Philippine Daily Inquirer. April 1, 2014. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Ardis, Kelly (September 1, 2015). "Filipino-Americans: The forgotten leaders of '65 grape strike". The Bakersfield Californian. TBC Media. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Berestein Rojas, Leslie (April 1, 2011). "The forgotten history of the Filipino laborers who worked with Cesar Chavez". SCPR. Pasadena. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2020. - ^ Soong, Tina (September 14, 2016). "Filipino American culture celebrations coming New Orleans-wide Oct. 8-9". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-305-85560-1.

- ISBN 978-0738581316.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-1-59213-729-9. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

Many Filipino student organizations have histories that coincide with the political awakenings of students on college campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s, For example, San Francisco Statue University's Pilipino American Collegiate Endeavor (PACE) was founded in 1967; the Pilipino American Alliance (PAA) at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, was funded in 1969; Samahang Pilipino at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), was founded in 1972; and Kababayan at the University of California, Irvine, was founded in 1974.

- ^ Almazol, Susan (February 23, 1969). "Change Comes to S.F. Filipino Community". S.F. Chronicle & Examiner. S.F. Chronicle & Examiner.

- ^ 1986 Congressional Record, Vol. 132, Page 9943 (May 7)

- ^ "First Fil-Am elected in the US Mainland: Larry Asera". Asian Journal. August 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-313-28902-6.(PDF) from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

"Family Connections, February Issue" (PDF). Hawaii State Bar Association. February 2015. Archived - ISBN 978-0-429-97648-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-47644-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8133-4716-5.

- ^ Yu, Brandon (August 11, 2017). "A community lost, a movement born". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Harrell, Ashley (April 30, 2011). "The International Hotel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Franko, Kantele (August 4, 2007). "I-Hotel, 30 years later – Manilatown legacy honored". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

Habal, Estella (2015). "San Francisco's International Hotel". Temple University Press. Temple University. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2018. - ^ "The Judge". News. Fordham Law. September 24, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

In June 1978, Laureta was confirmed as the first federal judge of Filipino ancestry in U.S. history.

Fujimoto, Dennis (June 23, 2017). "This judge still rules". The Garden Island. Kauai. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Bernardo, Rosemarie (November 22, 2005). "Far from home, nursing course offers chance for a new life". Star Bulletin. Honolulu. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Rueda, Nimfa U. (December 14, 2012). "US Senate confirms first Fil-Am federal judge". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Philippines. Retrieved February 8, 2020.Schofield shares a place in history with Judge Alfred Laureta, a Filipino-American who served as judge for the District of the Northern Mariana Islands from 1978 to 1988.

- ISBN 978-0-295-99190-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4053-9041-5.

- ^ "Ronald Quidachy, Longest-Serving Superior Court Judge, Retires". sfgate.com. Bay City News Service. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4381-0711-0. Archivedfrom the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-429-97648-3.from the original on January 12, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

"David M. Valderrama". Former Delegates. Maryland State Archives. September 29, 2015. Archived - ^ Ramos, George (December 18, 1990). "Long Fight Over for Filipino Vets : Citizenship: The promise of recognition made by President Franklin D. Roosevelt is finally fulfilled for guerrillas who fought alongside U.S. troops in World War II". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

2007 Congressional Record, Vol. 153, Page S13622 (23 May 2007) - ^ Berestein, Leslie (May 28, 1995). "A Debt Unpaid : In 1946, the U.S. Reneged on a Wartime Promise of Citizenship and Full Veterans' Benefits to Filipino Soldiers Who Played a Crucial Role Fighting With American Troops in the Pacific. When Congress Did Finally Grant Citizenship in 1990, More Than 20,000 Men Left the Philippines and Came to This Country--Many Settling In L.A. Here, They Continue to Wait for What Is Due Them. Poor and Too Old to Find Work, They Live Together in Cramped Apartments, Surviving on Meager Social Security Checks. Their Hope Is That One Day They Will Be Reunited With Their Loved Ones From Their Homeland". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4399-0543-2.from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

"Velma Veloria". Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. University of Washington. 2004. Archived - ^ a b c South, Garry (October 27, 2013). "The Fil-Am Community in California: Political Influence Doesn't Match the Numbers". Asian Journal. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018 – via Garry South Group.

- ISBN 978-0-16-080194-5.

- ^ Mariano, Connie; Martin, Michel (July 22, 2010). The White House Doctor. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

"Former White House Physician Connie Mariano Visits Stevens, Inspires Future Women Leaders". Campus & Community. Stevens Institute of Technology. March 1, 2018. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

"E. Connie Mariano, MD, FACP". American Medical Women's Association. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

Desselle, John R. (April 28, 2016). "Celebrating Asian American and Pacific Islanders in Naval History". The Sextant. United States Navy. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018. - ^ H.G., Reza (February 27, 1992). "Navy to Stop Recruiting Filipino Nationals : Defense: The end of the military base agreement with the Philippines will terminate the nearly century-old program". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

Rowe, Peter (July 27, 2015). "Deep ties connect Filipinos, Navy and San Diego". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on August 17, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018. - ISBN 978-0-7613-4089-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4408-2865-2.on September 25, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

"Sunday, 24 April 2011 Login Edit Feedback Historic Filipinotown With Mural/ Adobo Nation's La Chika". TFC. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

"Famous Fil Am Muralist Returns to Filipinotown". INQUIRER. June 22, 2006. Archived from the original - ^ Fortuna, Julius F. (August 23, 2007). "Yano takes over Philippine Army". The Manila Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

"Lieutenant General EDWARD SORIANO". Fort Riley. United States Army. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

Hackett, Gerald A. (September 23, 1994). "Executive Calendar" (PDF). United States Senate. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018. - doi:10.15779/Z38HS1B. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

Initially, nobody in the California state legislature knew of Joseph Ileto. When part of the legislature held an event about gun control two weeks after Joseph Ileto was killed, they talked about the Jewish kids, but they did not mention Joseph Ileto.

- ^ "Seattle to mark Carlos Bulosan's 100th with memorial events". Philippine Daily Inquirer. November 6, 2014. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

De Leon, Ferdinand M. (August 8, 1999). "Carlos Bulosan, In The Heart -- 'He Was An Integral Part Of Seattle ... And Of The Filipino Community'". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018. - ^ John A. Patterson (May 11, 2007). "Philippine Scout Heroes of WWII". History. Philippine Scouts Heritage Society. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ a b Aquino, Belinda (2005). "Filipinos in Hawaii". The Honolulu Advisor. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-107-37803-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7565-4095-1.

- ^ "Bataan Death March Memorial". las-cruces-media.org. Visit Las Cruces. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

The country's first federally funded monument honoring American and Filipino veterans of the Bataan Death March is on display at Veteran's Park in Las Cruces, NM. The monument was dedicated on April 13, 2002, marking the 60th anniversary of the march.

- ISBN 978-1-4408-2865-2.

- ^ "Citizenship Retention and Re-acquisition Act of 2003". Philippine Government, Bureau of Immigration. August 29, 2003. Archived from the original on February 8, 2005. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ "Implementing Rules and Regulations for R.A. 9225". Philippine Government, Bureau of Immigration. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-8032-0985-5.

- ^ "Garcetti Unveils Nation's First Filipino Veterans Memorial" (PDF) (Press release). Eric Garcetti, President, Los Angeles city council. November 13, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 20, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ^ a b 2014 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California (PDF) (Report). California Department of Transportation. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Amparo, Malou (June 5, 2012). "The First Filipino-American Highway in the U.S." Bakit Why. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "109th Congress, H.CON.RES.218, Recognizing the centennial of sustained immigration from the Philippines to the United States ..." U.S. Library of Congress. December 15, 2005. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Filipino Century Beyond Hawaii". Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawaii at Manoa. December 13–17, 2006. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7385-6954-3.

- ^ Johnson, Julie (August 9, 2008). "Stockton native to lead church". Recordnet.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Filipino-American History MOnth". California Teachers Association. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

"California Declares Filipino American History Month". San Francisco Business Times. September 10, 2009. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

"Filipino American History Month". San Diego Continuing Education. San Diego Community College District. April 21, 2017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018.

Ang, Walter (October 26, 2017). "Some books on Filipino American history". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018. - ISBN 978-0-691-14156-5.

- ^ "Mona Pasquil named interim Lt. Governor of CA". Asian Pacific Americans for Progress. November 6, 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Jan. 10: A. Gabriel Esteban is first Filipino American president of an American university". Northwest Asian Weekly. Seattle. February 3, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Marek, Lynne (March 8, 2018). "A layperson to lead DePaul University". Chicago Business. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Moral, Cheche V. (January 8, 2012). "A. Gabriel Esteban–the first Filipino (and lay) president of a major American university". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Makati City, Philippines. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

"Filipino-American named Seton Hall University President". Asian Journal. San Diego. February 18, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2020.[permanent dead link]

"Fil-Am UP grad is new Seton Hall University president". GMA News. Philippines. October 20, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2020. - ISBN 978-1-4671-2308-2.from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

Pastor, Christina DC (February 24, 2018). "First Fil-Am Federal Judge Lorna Schofield: 'I had no Filipino consciousness growing up'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

"CAPAC Leaders Applaud Schofield Nomination" (Press release). United States House of Representatives. Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus. April 25, 2012. Archived - ISBN 978-1-317-81391-0.. Balitang America. Daly City. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Constante, Agnes (April 19, 2018). "In California, Asian Americans find growing political power". NBC News. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Angeles, Steve (January 24, 2013). "The Filipino Champion: Rob Bonta, Making History in California" - ^ Pimentel, Joseph (October 9, 2013). "California writing Filipino Americans into the history books". Public Radio International. Minneapolis, Minnesota. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ "Six of Weber's 2014 Bills Signed by Governor". Dr. Shirley Weber. California State Assembly Democratic Caucus. October 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ a b Guillermo, Emil (December 18, 2015). "California School to Bear Names of Filipino-American Labor Leaders Itliong, Vera Cruz". NBC News. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

Revilla, Linda (October 7, 2015). "Remembering Our Manongs And The Delano Grape Strike". Positively Filipino. Burlingame, California. Retrieved February 19, 2020. - ^ Rocha, Veronica (February 23, 2015). "2 Inland Empire men sentenced in terrorist plot to kill Americans". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

Angeles, Steve (September 26, 2014). "SoCal Jury finds Filipino Terror Suspect Guilty". Balitang America. ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

Fernandez, Alexia (August 9, 2016). "Philippine lawmaker wants to ban Trump from the country". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Johnson, Jenna (August 5, 2016). "Donald Trump now says even legal immigrants are a security threat". Washington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Oriel, Christina M. (August 19, 2016). "Trump: 'Extreme vetting' needed for immigrants to US". Asian Journal. San Francisco. Retrieved February 19, 2020. - ^ Parr, Rebecca (August 11, 2016). "Union City school first in nation named for Filipino-Americans". Mercury News. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

"Union City school to be first named after Filipino-Americans in US". KGO. San Francisco. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018. - ^ Lam, Charles (March 6, 2017). "First Filipino-American Bishop to Lead Diocese to Be Installed". NBC News. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

Mikita, Caoline (March 7, 2017). "Oscar Solis is the first Filipino American Catholic Bishop, a Northern Utah congregation celebrates". KSL. Salt Lake City. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

Brockhaus, Hannah (January 11, 2017). "First Filipino-Born Bishop Will Head a U.S. Diocese". EWTN. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018 – via National Catholic Register. - ^ Sciaudone, Christiana (February 11, 2004). "Filipino American Bishop Is the First". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Bureau, INQUIRER.net US. "Fil-Am writer wins top U.S. prize for children's novel | INQUIRER.net". usa.inquirer.net. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Burlingame, Jon (March 5, 2018). "'Remember Me' Songwriter Robert Lopez Becomes First-Ever 'Double EGOT' Winner". Variety. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

Gibbs, Alexandra (March 6, 2018). "Songwriter Robert Lopez becomes double EGOT winner after Oscars success". CNBC. United States. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ Ramos, Dino-Ray; Tartaglione, Nancy (January 6, 2019). "Darren Criss Says "It's A Great Privilege" To Be First First Filipino American To Win Golden Globe". Deadline. Los Angeles. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

"Darren Criss the first Filipino-American to win Golden Globe". Asia Times. Hong Kong. January 7, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

"What it means for Darren Criss to be first Fil-Am Golden Globe winner". ABS-CBN News. Philippines. January 8, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2020. - ^ "How COVID-19 has taken a toll on Filipino-American healthcare workers". WNYW. New York City. May 22, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

Martin, Nina; Yeung, Bernice (May 3, 2020). ""Similar to Times of War": The Staggering Toll of COVID-19 on Filipino Health Care Workers". ProPublica. New York City. Retrieved May 31, 2020. - ^ Orecchio-Egresitz, Haven; Canales, Katie; Lee, Yeji Jesse (May 3, 2020). "American hospitals have lost dozens of medical workers to the coronavirus. Here are some of their stories". Business Insder. New York City. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

Huang, Jose (May 8, 2020). "A Fifth Of California's Nurses Are Filipino. Their Burden Of The Coronavirus Pandemic Is Fast Emerging". LAist. Pasadena: Southern California Public Radio. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

"Filipina Nurse Who Died from COVID-19 Honored By Community". Balitang America. Redwood City, California. May 7, 2020. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

"Lost On The Frontline". Kaiser Health News. San Francisco. The Guardian. May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

Wong, Tiffany (July 21, 2020). "Little noticed, Filipino Americans are dying of COVID-19 at an alarming rate". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

Constante, Agnes (December 7, 2020). "Filipino Americans have been hit hard by COVID-19, but the available data masks the impact". Center for Health Journalism. USC Annenberg. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

Constante, Agnes (June 4, 2021). "Filipino American nurses, reflecting on disproportionate Covid toll, look ahead". NBC News. Retrieved October 22, 2021. - ^ Srikrishnan, Maya (December 6, 2021). "The First Year of COVID: Filipinos Were Among Hardest Hit, But Hidden by Data". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

This reflected a nationwide trend. A September 2020 report from National Nurses United, the country's largest nursing union, found that even though Filipino nurses make up only 4 percent of the nursing population nationwide, nearly a third of nurses who have died from the coronavirus in the country are Filipino.

Further reading

- Fred Cordova (1983). Filipinos, Forgotten Asian Americans: A Pictorial Essay, 1763-circa 1963. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8403-2897-7.

- Filipino Oral History Project (1984). Voices, a Filipino American oral history. Filipino Oral History Project.

- ISBN 978-0-7910-2187-3.

- Takaki, Ronald (1998) [1989]. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (Updated and revised ed.). New York: Back Bay Books. ISBN 0-316-83130-1.

- John Wenham (1994). Filipino Americans: Discovering Their Past for the Future (VHS). Filipino American National Historical Society.

- Joseph Galura; Emily P. Lawsin (2002). 1945-1955 : Filipino women in Detroit. OCSL Press, University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-9638136-4-0.

- Choy, Catherine Ceniza (2003). Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History. ISBN 9780822330899.

Filipinos Texas.

- Bautista, Veltisezar B. (2008). The Filipino Americans: (1763–present) : their history, culture, and traditions. ISBN 9780931613173.

Filipino American National Historical Society books published by Arcadia Publishing

- Estrella Ravelo Alamar; Willi Red Buhay (2001). Filipinos in Chicago. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-1880-0.

- Mel Orpilla (2005). Filipinos in Vallejo. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2969-1.

- Mae Respicio Koerner (2007). Filipinos in Los Angeles. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4729-9.

- Carina Monica Montoya (2008). Filipinos in Hollywood. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5598-0.

- Evelyn Luluguisen; Lillian Galedo (2008). Filipinos in the East Bay. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5832-5.

- Dawn B. Mabalon, Ph.D.; Rico Reyes; Filipino American National Historical So (2008). Filipinos in Stockton. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5624-6.

- Carina Monica Montoya (2009). Los Angeles's Historic Filipinotown. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6954-3.

- Florante Peter Ibanez; Roselyn Estepa Ibanez (2009). Filipinos in Carson and the South Bay. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7036-5.

- Rita M. Cacas; Juanita Tamayo Lott (2009). Filipinos in Washington. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6620-7.

- Dorothy Laigo Cordova (2009). Filipinos in Puget Sound. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7134-8.

- Judy Patacsil; Rudy Guevarra, Jr.; Felix Tuyay (2010). Filipinos in San Diego. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-8001-2.

- Tyrone Lim; Dolly Pangan-Specht; Filipino American National Historical Society (2010). Filipinos in the Willamette Valley. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-8110-1.

- Theodore S. Gonzalves; Roderick N. Labrador (2011). Filipinos in Hawai'i. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7608-4.

- Filipino American National Historical Society; Manilatown Heritage Foundation; Pin@y Educational Partnerships (February 14, 2011). Filipinos in San Francisco. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-2524-8.

- Elnora Kelly Tayag (May 2, 2011). Filipinos in Ventura County. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-2429-6.

- Eliseo Art Arambulo Silva (2012). Filipinos of Greater Philadelphia. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9269-5.

- Kevin L. Nadal; Filipino-American National Historical Society (March 30, 2015). Filipinos in New York City. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4396-5056-1.

External links

- Filipino Home

- History of Filipino Americans in Seattle

- "City of Los Angeles declares Historic Filipinotown". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- Filipino Cannery Unionism Across Three Generations 1930s–1980s, Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

- Manilamen: The Filipino Roots in America (archived from the original on 2008-05-14)

- Pinoy in the War of 1812

- Filipino Veterans of War of 1812 and American Civil War (archived from the original on 2007-02-06)

- History of Filipino Americans in Chicago

- Census 2000 Brief: The Asian Population: 2000