History of Guyana

| History of Guyana | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

|

||

|

||

|

| ||

The history of Guyana begins about 35,000 years ago with the arrival of humans coming from Eurasia. These migrants became the Carib and Arawak tribes, who met Alonso de Ojeda's first expedition from Spain in 1499 at the Essequibo River. In the ensuing colonial era, Guyana's government was defined by the successive policies of the French, Dutch, and British settlers. During the colonial period, Guyana's economy was focused on plantation agriculture, which initially depended on slave labor. Guyana saw major slave rebellions in

After his unexpected death in 1985, power was peacefully transferred to

Pre-colonial Guyana and first contacts

The first people to reach Guyana made their way from Siberia, perhaps as far back as 20,000 years ago. These first inhabitants were

Historians speculate that the Arawaks and Caribs originated in the South American

Colonial Guyana

Early colonization

The

In 1621 the government of the Netherlands gave the newly formed Dutch West India Company complete control over the trading post on the Essequibo. This Dutch commercial concern administered the colony, known as Essequibo, for more than 170 years. The company established a second colony, on the Berbice River southeast of Essequibo, in 1627.[7] Although under the general jurisdiction of this private group, the settlement, named Berbice, was governed separately. Demerara, situated between Essequibo and Berbice, was settled in 1741 and emerged in 1773 as a separate colony under the direct control of the Dutch West India Company. In these colonies, enslaved Africans produced "coffee, sugar and cotton...for the Dutch market."[10]

Although the Dutch colonizers initially were motivated by the prospect of trade in the Caribbean, their possessions became significant producers of crops. The growing importance of agriculture was indicated by the export of 15,000 kilograms of

The most famous uprising of the enslaved Africans, the

Transition to British Rule

Eager to attract more settlers, in 1746 the Dutch authorities opened the area near the Demerara River to British immigrants. British plantation owners in the Lesser Antilles had been plagued by poor soil and erosion, and many were lured to the Dutch colonies by richer soils and the promise of land ownership. The influx of British citizens was so great that by 1760 the English constituted a majority of the European population of Demerara. By 1786 the internal affairs of this Dutch colony were effectively under British control,[14] though two-thirds of the plantation owners were still Dutch.[15] Under the British, the colonies became a huge cotton producer. This was thanks to the groundwork laid "during the Dutch colonial era".[10]

As economic growth accelerated in Demerara and Essequibo, strains began to appear in the relations between the planters and the Dutch West India Company. Administrative reforms during the early 1770s had greatly increased the cost of government. The company periodically sought to raise taxes to cover these expenditures and thereby provoked the resistance of the planters. In 1781 a war broke out between the Netherlands and Britain, which resulted in the British occupation of Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara.[16] Some months later, France, allied with the Netherlands, seized control of the colonies. The French governed for two years, during which they constructed a new town, Longchamps, at the mouth of the Demerara River. When the Dutch regained power in 1784, they moved their colonial capital to Longchamps, which they renamed Stabroek. The capital was in 1812 renamed Georgetown by the British.[17]

The return of Dutch rule reignited conflict between the planters of Essequibo and Demerara and the Dutch West India Company. Disturbed by plans for an increase in the slave tax and a reduction in their representation on the colony's judicial and policy councils, the colonists petitioned the Dutch government to consider their grievances. In response, a special committee was appointed, which proceeded to draw up a report called the Concept Plan of Redress. This document called for far-reaching constitutional reforms and later became the basis of the British governmental structure. The plan proposed a decision-making body to be known as the Court of Policy. The judiciary was to consist of two courts of justice, one serving Demerara and the other Essequibo. The membership of the Court of Policy and of the courts of justice would consist of company officials and planters who owned more than twenty-five slaves. The Dutch commission that was assigned the responsibility of implementing this new system of government returned to the Netherlands with extremely unfavourable reports concerning the Dutch West India Company's administration. The company's charter, therefore, was allowed to expire in 1792 and the Concept Plan of Redress was put into effect in Demerara and Essequibo. Renamed the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo, the area then came under the direct control of the Dutch government. Berbice maintained its status as a separate colony.[18]

The catalyst for formal British takeover was the

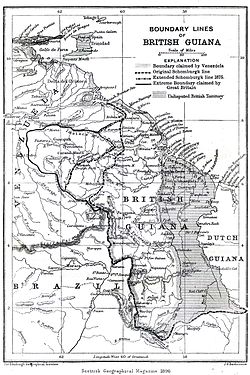

Origins of the border dispute with Venezuela

When Britain gained formal control over what is now Guyana in 1814,

The discovery of gold in the contested area in the late 1850s reignited the dispute. British settlers moved into the region and the British Guiana Mining Company was formed to mine the deposits. Over the years, Venezuela made repeated protests and proposed arbitration, but the British government was uninterested. Venezuela finally broke diplomatic relations with Britain in 1887 and appealed to the United States for help. The British at first rebuffed the United States government's suggestion of arbitration, but when President Grover Cleveland threatened to intervene according to the Monroe Doctrine, Britain agreed to let an international tribunal arbitrate the boundary in 1897.[25]

For two years, the tribunal consisting of two Britons, two Americans, and a Russian studied the case in Paris (France).[26] Their three-to-two decision, handed down in 1899, awarded 94 percent of the disputed territory to British Guiana. Venezuela received only the mouths of the Orinoco River and a short stretch of the Atlantic coastline just to the east. Although Venezuela was unhappy with the decision, a commission surveyed a new border in accordance with the award, and both sides accepted the boundary in 1905. The issue was considered settled for the next half-century.[27]

From 1990 to 2017, the

The early British Colony and the labor problem

Political, economic, and social life in the 19th century was dominated by a European planter class. Although the smallest group in terms of numbers, members of the

Colonial life was changed radically by the demise of slavery. Although the international slave trade was

For some plantation owners, Guyana had more "fertile territory"

Emancipation also resulted in the introduction of new ethnic and cultural groups into British Guiana.[7] The departure of the Afro-Guyanese from the sugar plantations soon led to labour shortages. After unsuccessful attempts throughout the 19th century to attract Portuguese workers from Madeira, the estate owners were again left with an inadequate supply of labour. Portuguese Guyanese had not taken to plantation work and soon moved into other parts of the economy, especially retail business, where they became competitors with the new Afro-Guyanese middle class. Some 14,000 Chinese came to the colony between 1853 and 1912. Like their Portuguese predecessors, the Chinese Guyanese forsook the plantations for the retail trades and soon became assimilated into Guianese society.[24]

Concerned about the plantations' shrinking labor pool and the potential decline of the

Political and social awakenings

Nineteenth-century British Guiana

The constitution of the British colony favoured the white and South Asian planters. Planter political power was based in the Court of Policy and the two courts of justice, established in the late 18th century under Dutch rule. The Court of Policy had both legislative and administrative functions and was composed of the governor, three colonial officials, and four colonists, with the governor presiding. The courts of justice resolved judicial matters, such as licensing and civil service appointments, which were brought before them by petition.[37] In addition, the first police force for the colony was established in July 1839.[38]

Raising and disbursing revenue was the responsibility of the Combined Court, which included members of the Court of Policy and six additional financial representatives appointed by the College of Electors. In 1855 the Combined Court also assumed responsibility for setting the salaries of all government officials. This duty made the Combined Court a centre of intrigues resulting in periodic clashes between the governor and the planters.[37]

Other Guyanese began to demand a more representative political system in the 19th century. By the late 1880s, pressure from the new Afro-Guyanese middle class was building for constitutional reform. In particular, there were calls to convert the Court of Policy into an assembly with ten elected members, to ease voter qualifications, and to abolish the College of Electors. Reforms were resisted by the planters, led by Henry K. Davson, owner of a large plantation. In London the planters had allies in the West India Committee and also in the West India Association of Glasgow, both presided over by proprietors with major interests in British Guiana. During this period, Indian migrants started to move to British Guiana and settle there.[39]

Constitutional revisions in 1891 incorporated some of the changes demanded by the reformers. The planters lost political influence with the abolition of the College of Electors and the relaxation of voter qualification. At the same time, the Court of Policy was enlarged to sixteen members; eight of these were to be elected members whose power would be balanced by that of eight appointed members. The Combined Court also continued, consisting, as previously, of the Court of Policy and six financial representatives who were now elected. To ensure that there would be no shift of power to elected officials, the governor remained the head of the Court of Policy; the executive duties of the Court of Policy were transferred to a new

Political changes were accompanied by social change and jockeying by various ethnic groups for increased power. The British and Dutch planters refused to accept the Portuguese as equals and sought to maintain their status as aliens with no rights in the colony, especially voting rights. The political tensions led the Portuguese to establish the Reform Association. After the anti-Portuguese riots of 1898, the Portuguese recognized the need to work with other disenfranchised elements of Guyanese society, in particular the Afro-Guyanese. By around the start of the 20th century, organizations including the Reform Association and the Reform Club began to demand greater participation in the colony's affairs. These organizations were largely the instruments of a small but articulate emerging middle class. Although the new middle class sympathized with the working class, the middle-class political groups were hardly representative of a national political or social movement. Indeed, working-class grievances were usually expressed in the form of riots.[41]

Political and social changes in the early twentieth century

1905

Even though World War I was fought far beyond the borders of British Guiana, the war altered Guyanese society. The Afro-Guyanese who joined the British military became the nucleus of an elite Afro-Guyanese community upon their return. World War I also led to the end of East Indian indentured service. British concerns over political stability in India and criticism by Indian nationalists that the program was a form of human bondage caused the British government to outlaw indentured labour in 1917.[41]

In the closing years of World War I, the colony's first trade union was formed. The

The second trade union, the British Guiana Workers' League, was established in 1931 by Alfred A. Thorne, who served as the League's leader for 22 years. The League sought to improve the working conditions for people of all ethnic backgrounds in the colony. Most workers were of West African, East Indian, Chinese and Portuguese descent, and had been brought to the country under a system of forced or indentured labor.[42]

After World War I, new economic interest groups began to clash with the Combined Court. The country's economy had come to depend less on sugar and more on rice and bauxite, and producers of these new commodities resented the sugar planters' continued domination of the Combined Court. Meanwhile, the planters were feeling the effects of lower sugar prices and wanted the Combined Court to provide the necessary funds for new drainage and irrigation programs.

To stop the bickering and resultant legislative paralysis, in 1928 the

The

In British Guiana, the

The Moyne Commission report in 1939 was a turning point for British Guiana. It urged extending the franchise to women and persons not owning land and encouraged the emerging trade union movement. However, none of the Moyne Commission's recommendations were immediately implemented because of the outbreak of World War II.[44] The country's rice industry, which had stagnated between the two World Wars, expanded, with Guyana gaining a "virtual monopoly of the West Indies market" by the war's end.[45]

With the fighting far away, and the country as part of

Pre-independence government

Development of political parties

At the end of World War II, political awareness and demands for independence grew in all segments of society. The immediate postwar period witnessed the founding of Guyana's major political parties. The

Cheddi Jagan

Jagan returned to British Guiana in October 1943 and was soon joined by his American wife, the former

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham

Born in 1923,

The social strata of the urban Afro-Guyanese community of the 1930s and 1940s included a mulatto or "coloured" elite, a black professional middle class, and, at the bottom, the black working class. Unemployment in the 1930s was high. When war broke out in 1939, many Afro-Guyanese joined the military, hoping to gain new job skills and escape poverty. When they returned home from the war, however, jobs were still scarce and discrimination was still a part of life.

Founding of the PAC and PPP

The springboard for Jagan's political career was the Political Affairs Committee (PAC), formed in 1946 as a discussion group. The new organization published the

In the November 1947 general elections, the PAC put forward several members as independent candidates. The PAC's major competitor was the newly formed

After the PAC, Jagan's next major step was the founding of the

The PPP's initial leadership was multi-ethnic and left of centre, but hardly revolutionary. Jagan became the leader of the PPP's parliamentary group, and Burnham assumed the responsibilities of party chairman. Other key party members included Janet Jagan, Brindley Benn[54] and Ashton Chase, both PAC veterans. The new party's first victory came in the 1950 municipal elections, in which Janet Jagan won a seat. Cheddi Jagan and Burnham failed to win seats, but Burnham's campaign made a favourable impression on many Afro-Guyanese citizens.[55]

From its first victory in the 1950 municipal election, the PPP gathered momentum.

A British commission in 1950 recommended universal adult suffrage and the adoption of a

The first PPP government

Once the new constitution was adopted, elections were set for

The PPP's first administration was brief. The legislature opened on May 30, 1953. Already suspicious of Jagan and the PPP's radicalism, conservative forces in the business community were further distressed by the new administration's program of expanding the role of the state in the economy and society.[57] The PPP also sought to implement its reform program at a rapid pace, which brought the party into confrontation with the governor and with high-ranking civil servants who preferred more gradual change. The issue of civil service appointments also threatened the PPP, in this case from within. Following the 1953 victory, these appointments became an issue between the predominantly Indo-Guyanese supporters of Jagan and the largely Afro-Guyanese backers of Burnham. Burnham threatened to split the party if he were not made sole leader of the PPP.[60] A compromise was reached by which members of what had become Burnham's faction received ministerial appointments.

The PPP's introduction of the

Following this action, Britain would keep Guyana under

The second PPP government

The

The 1957 elections were convincingly won by

Jagan's veto of British Guiana's participation in the West Indies Federation, favored by the British colonial authorities,[65][66] caused his party to lose significant Afro-Guyanese support.[67] In the late 1950s, the British Caribbean colonies had been actively negotiating establishment of a West Indies Federation. The PPP had pledged to work for the eventual political union of British Guiana with the Caribbean territories. The Indo-Guyanese, who constituted a majority in Guyana, were apprehensive of becoming part of a federation in which they would be outnumbered by people of African descent.

Burnham learned an important lesson from the 1957 elections. He could not win if supported only by the lower-class, urban Afro-Guyanese. He needed

Following the 1957 elections, Jagan rapidly consolidated his hold on the Indo-Guyanese community. Though candid in expressing his admiration for

PPP re-election and aftermath

The 1961 elections were a bitter contest between the PPP, the PNC, and the United Force (UF), a conservative party representing big business, the

Jagan's administration became increasingly friendly with communist and leftist regimes; for instance, Jagan refused to observe the United States embargo on communist

Jagan would become others harbored suspicions of him. Although he would even meet with President Kennedy in October 1962, he would believe that the CIA had fomented riots earlier that year when he introduced an austerity budget which increased a tax increase which "fell mainly on Guiana's African and mixed population".

From 1961 to 1964, Jagan was confronted with a destabilization campaign conducted by the PNC and UF. In addition to domestic opponents of Jagan, an important role was played by the

To counter the MPCA with its link to Burnham, the PPP formed the

By early 1963, the diplomatic representation of the U.S. in Georgetown changed to general consulate, which included a "CIA communications backchannel". Through that backchannel, Burham provided assurances to the CIA about what his political program would be, resulting in the agency sending him financial assistance.[49] He had become the "CIA's instrument" against Jagan. At the same time, Burham supported proportional representation, as did D'Augilar, which the government resisted, leading to more discord.[49] Before the election in 1964 began, the British unilaterally imposed a "proportional representation electoral format" in Guyana.[7] McCabe met with the unionists in the country, the CIA proposed a paper which reportedly outlined "a project to influence that election". In addition, the CIA would start a political party to draw off the PPP's support.[49] Jagan retained no desire to make a coalition government with Burnham and the PPP.[73]

Jagan's ouster and Burnham's victory

The PPP government responded to the strike in March 1964 by publishing a new Labour Relations Bill almost identical to the 1953 legislation that had resulted in British intervention. Regarded as a power play for control over a key labor sector, introduction of the proposed law prompted protests and rallies throughout the capital.[77] Riots broke out on April 5; they were followed on April 18 by a general strike. By May 9, the governor was compelled to declare a state of emergency. Nevertheless, the strike and violence continued until July 7,[57] when the Labour Relations Bill was allowed to lapse without being enacted. To bring an end to the disorder, the government agreed to consult with union representatives before introducing similar bills. These disturbances exacerbated tension and animosity between the two major ethnic communities and made a reconciliation between Jagan and Burnham, who had different political outlooks,[78] an impossibility.

Jagan's term had not yet ended when another round of labor unrest rocked the colony. The pro-PPP GIWU, which had become an umbrella group of all labor organizations, called on sugar workers to strike in January 1964.[43] To dramatize their case, Jagan led a march by sugar workers from the interior to Georgetown. This demonstration ignited outbursts of violence that soon escalated beyond the control of the authorities.[79] On May 22, the governor finally declared another state of emergency. The situation continued to worsen, and in June the governor assumed full powers, rushed in British troops to restore order, and proclaimed a moratorium on all political activity. By the end of the turmoil, 160 people were dead and more than 1,000 homes had been destroyed.[50]

In an effort to quell the turmoil, the country's political parties asked the British government to modify the constitution to provide for more proportional representation. The colonial secretary proposed a fifty-three member unicameral legislature. Despite opposition from the ruling PPP, all reforms were implemented and new elections set for October 1964.[80] As Jagan feared, the PPP lost the general elections of 1964.[49] The politics of aapan jaat, Guyanese Hindustani for "vote for your own kind", were becoming entrenched in Guyana. The PPP won 46 percent of the vote and twenty-four seats, which made it the largest single party but short of an overall majority. However, the PNC, which won 40 percent of the vote and twenty-two seats, and the UF, which won 11 percent of the vote and seven seats, formed a coalition. The socialist PNC and unabashedly capitalist UF had joined forces to keep the PPP out of office for another term.[59] Jagan called the election fraudulent and refused to resign as prime minister. The constitution was amended to allow the governor to remove Jagan from office.[50][57]

Burnham became prime minister on December 14, 1964.[43] Following this, the U.S. began a strong working relationship with the country. The U.S. later encouraged loans and economic assistance from the International Monetary Fund to limit Cuban and Soviet influence and promote the country's economic development.[48] Following his victory, Burham would retain a "firm grip" on the country until his death in 1985, which involved constitutional changes, elevating the PPP, tight media control, "state violence to suppress dissent," while those of Indian descent experienced systemic discrimination. The British and Americans believed he was an "lesser evil" as compared to Jagan, who was sidelined for "three decades" because he was described as a Marxist.[50] The U.S.-British effort, which began in 1953, to force Chagan out of office had been successful.[81] Some scholars described Burnham's victory as the beginning of a "long, repressive era" in the country's history.[59]

Independence and the Burnham era

Burnham in power

In the first year under Forbes Burnham, conditions in the colony began to stabilize. The new coalition administration broke diplomatic ties with Cuba and implemented policies that favoured local investors and foreign industry. This included the establishment of the Bank of Guyana in October 1965.[82] The colony applied the renewed flow of Western aid to further development of its infrastructure. A constitutional conference was held in London; the conference set May 26, 1966 as the date for the colony's independence from the United Kingdom. The sitting of the country's first Parliament happened on May 26, 1966, when the Guyana Independence Act came into effect,[83] and day of the country's independence.[84] The country also joined the Commonwealth of Nations in 1966.[7]

The newly independent Guyana at first sought to improve relations with its neighbours. For instance, in December 1965 the country had become a charter member of the

The Central Intelligence Agency later argued that following independence in 1966, the country has been "ruled mostly by socialist-oriented governments."[5] In February 1967, Guyana would begin a standby arrangement with the International Monetary Fund. Such arrangements would continue, off-and-on until 1979.[89]

Another challenge to the newly independent government came at the beginning of January 1969, with the

The cooperative republic

The

After the 1968 elections, Burnham's policies, despite a continued CIA subsidy,

On February 23, 1970, Guyana declared itself a "cooperative republic" and cut all ties to the

In the early 1970s, electoral fraud became blatant in Guyana. PNC victories always included overseas voters, who consistently and overwhelmingly voted for the ruling party.[7] The police and military intimidated the Indo-Guyanese. The army was accused of tampering with ballot boxes.[100] Some scholars have noted that opposition, at the time, to the Guyanese government was multiracial. Also, it was said that in 1973, the overseas vote was "padded" while real people were disenfranchised, even recognized by U.S. Embassy officials.[50]

Considered a low point in the democratic process, the

Government

Burnham's consolidation of power in Guyana was not total; opposition groups were tolerated within limits. For instance, in 1973 the Working People's Alliance (WPA) was founded.[104] Opposed to Burnham's authoritarianism, the WPA was a multi-ethnic combination of politicians and intellectuals that advocated racial harmony, free elections, and democratic socialism. Although the WPA did not become an official political party until 1979, it evolved as an alternative to Burnham's PNC and Jagan's PPP.[7]

Jagan's political career continued to decline in the 1970s. Outmaneuvered on the parliamentary front, the PPP leader tried another tactic. In April 1975, the PPP ended its boycott of parliament with Jagan stating that the PPP's policy would change from noncooperation and civil resistance to critical support of the Burnham regime. Soon after, Jagan appeared on the same platform with Prime Minister Burnham at the celebration of ten years of Guyanese independence, on May 26, 1976.[105] The following year, workers in the Guyanese sugar industry would strike "135 days for economic justice", ending their action on January 5, 1978.[106] Despite Jagan's conciliatory move, Burnham had no intention of sharing powers and continued to secure his position.

The PNC postponed the 1978 elections, opting instead for a referendum to be held in July 1978,.

Jonestown and the 1978 massacre

Burnham's control over Guyana began to weaken when the

The People's Temple of Christ was regarded by members of the Guyanese government as a model agricultural community that shared its vision of settling the hinterland and its view of cooperative socialism. The fact that the People's Temple was well equipped with openly flaunted weapons hinted that the community had the approval of members of the PNC's inner circle.Complaints of abuse by leaders of the cult prompted United States congressman Leo Ryan to fly to Guyana to investigate.[117][118] The San Francisco-area representative was shot and killed by members of the People's Temple as he was boarding an airplane in Port Kaituma to return to Georgetown. Fearing further publicity, Jones and more than 900 of his followers died in a massive communal murder and suicide.[119][120]

The November 1978 Jonestown massacre suddenly put the Burnham government under intense foreign scrutiny, especially from the United States. Investigations into the massacre led to allegations that the Guyanese government had links to the People's Temple.[121][122][123] Originally, the U.S. government wanted to bury the bodies from the massacre in a mass grave, but the Guyanese government insisted they be removed, with Jonestown Memorial Fund member Rebecca Moore arguing it was "an American problem dumped in their laps".[112]

Burnham's last years

Although the bloody memory of Jonestown faded, Guyanese politics experienced a violent year in 1979. Some of this violence was directed against the WPA, which had emerged as a vocal critic of the state and of Burnham in particular. One of the party's leaders, Walter Rodney, and several professors at the University of Guyana were arrested on arson charges. The professors were soon released, and Rodney was granted bail. WPA leaders then organized the alliance into Guyana's most vocal opposition party.[50] The events in Jonestown were also said to increase opposition to the government, with the "authoritarian nature" of the government said to cause "loss of both foreign and domestic supporters."[124] Even so, the Guyanese government would begin an extended fund faculty with the International Monetary Fund, which would continue until July 1980. That aid would then be replaced by a similar financial instrument, which lasted to July 1982.[89]

As 1979 wore on, the level of violence continued to escalate. In October Minister of Education Vincent Teekah was mysteriously shot to death. The following year, Rodney was killed by a car bomb. The PNC government quickly accused Rodney of being a terrorist who had died at the hands of his own bomb and charged his brother Donald with being an accomplice. Later investigation implicated the Guyanese government, however. Rodney was a well-known leftist, and the circumstances of his death damaged Burnham's image with many leaders and intellectuals in less-developed countries who earlier had been willing to overlook the authoritarian nature of his government.[125] Although Burham's government was backed by the United States, privately, diplomats were skeptical, and believed that the Guyanese authorities had "covered up evidence" in Rodney's assassination. Even so, the United States continued to support the country's economy as part of U.S. "Cold War policy in the Caribbean and Central and South America."[48] A commission on his death was later convened by the PPP government in 2014.[50]

A new constitution was promulgated in 1980. The old ceremonial post of president was abolished, and the

The economic crisis facing Guyana in the early 1980s deepened considerably, accompanied by the rapid deterioration of public services, infrastructure, and overall quality of life. The country became "one of the poorest" in the region.[127] Blackouts occurred almost daily, and water services were increasingly unsatisfactory. The litany of Guyana's decline included shortages of rice and sugar (both produced in the country), cooking oil, and kerosene. While the formal economy sank, the black market economy in Guyana thrived.[128] Richard Dwyer, deputy chief of mission in Guyana described the country as "riddled by corruption" and said the Burnham government had politics which had become "increasingly unsavory." Later, George B. Roberts Jr., then the U.S. ambassador to Guyana, found Burham distasteful, but called Cheddi Jagan "still unacceptable" to the U.S.[48]

In the 1980s, the "largely untouched forests" of Guyana were logged after the Burnham government implemented a

In 1983, Burnham urged

Hoyte to present

Hoyte and economic liberalization

Despite concerns that the country was about to fall into a period of political instability, the transfer of power went smoothly. Vice President Desmond Hoyte became the new executive president and leader of the PNC. His initial tasks were threefold: to secure authority within the PNC and national government, to take the PNC through the December 1985 elections, and to revitalize the stagnant economy. The State Department would later stated that the Guyanese government sought to improve diplomatic relations with the U.S., coupled with a shift "toward political nonalignment" and away from "state socialism and one-party control" to expanded freedom of assembly and press and a market economy.[132] In 1986, his government would submit a letter of intent to the IMF and World Bank, indicating commitment and willingness to economic policy reform.[133]

Hoyte's first two goals were easily accomplished. The new leader took advantage of factionalism within the PNC to quietly consolidate his authority. The December 1985 elections gave the PNC 79 percent of the vote and forty-two of the fifty-three directly elected seats.[134] Eight of the remaining eleven seats went to the PPP, two went to the UF, and one to the WPA. Charging fraud, the opposition boycotted the December 1986 municipal elections. With no opponents, the PNC won all ninety-one seats in local government.[7]

Revitalizing the economy proved more difficult. As a first step, Hoyte gradually moved to embrace the private sector, which would manifest in "significant privatization" in many economic sectors by the 1990s.[135] Hoyte's administration lifted all curbs on foreign activity and ownership in 1988.[citation needed] Although the Hoyte government did not completely abandon the authoritarianism of the Burnham regime, it did make certain political reforms. Hoyte abolished overseas voting and the provisions for widespread proxy and postal voting. Independent newspapers were given greater freedom, and political harassment abated considerably.[citation needed] A law passed in 1991, later amended in 1995, allowing individuals to "establish business enterprises", and dispose, or acquire or interest.[135] The Hayte government would also renew aid arrangements with the IMF. From July 1990 to December 1991, the country would have a Standby Arrangement with the IMF, in conjunction with an Extended Credit Facility which lasted until December 1993.[89][136] As one scholar, noting Canadian involvement in the country's economy, put it, "to say that structural adjustment was harsh would be an understatement".[137]

Jagan's years in power

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter visited Guyana to lobby for the resumption of free elections. On October 5, 1992, a new National Assembly and regional councils were elected in the first Guyanese election since 1964 to be internationally recognized as free and fair. Cheddi Jagan of the PPP was elected and sworn in as president on October 9, 1992.[49][5][59] This reversed the monopoly Afro-Guyanese traditionally had over Guyanese politics. The poll was marred by violence however.

Before Jagan took office, a new International Monetary Fund Structural Adjustment programme was introduced which led to an increase in the GDP whilst also eroding real incomes and hitting the middle-classes hard.[138][139] Jagan's government debated whether to continue to implement the IMF programme agreed to under the former administration, and decided to stick with the programme, while Jagan argued publicly that the working class of the country were harmed by these programmes.[140] The country would join the World Trade Organization in 1995. The previous year, Guyana had joined the World Intellectual Property Organization.[135] Guyana would also continue economic arrangements with the IMF. From July 1994 to April 1998, the country would have an Extended Credit Facility with the IMF, which continued, almost uninterrupted until September 2005.[89]

When President Jagan died of a heart attack in March 1997, Prime Minister

The Jadgeo years

In 2000, Guyana would be described in The 21st Century World Atlas

In December 2002, Hoyte died, with

The PPP/C would win re-election in 2006. However, a political opposition party, Alliance for Change, formed by those who had defected from the PPP/C and the PNC, performed "surprisingly well", gaining it six seats in the country's parliament.[59] Previously, scholars had argued that the country had suffered from violence and rioting during the election campaigns in 1996 and 2001.[143]

Severe flooding following torrential rainfall wreaked havoc in Guyana beginning in January 2005. The downpour, which lasted about six weeks, inundated the coastal belt, caused the deaths of 34 people, and destroyed large parts of the rice and sugarcane crops.[59] The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated in March that the country would need $415 million for recovery and rehabilitation. About 275,000 people—37% of the population—were affected in some way by the floods. In 2013, the Hope Canal was completed to address the flooding.[144]

In May 2008, President Bharrat Jagdeo was a signatory to the UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations. On February 12, 2010, Guyana ratified its membership in the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR).[145][146]

Coalitions, oil drilling, and political instability

In December 2011, President Bharrat Jagdeo was succeeded by

Guyana began a contract with

In May 2015, David Granger of A Partnership for National Unity and Alliance for Change (APNU+AFC) narrowly won the elections. He represented the alliance of Afro-Guyanese parties, which had a slim parliamentary majority.[152][59] Granger was later sworn is as the new President of Guyana.[153][5] The following year, the country celebrated its 50 years of independence, with huge celebrations attended by Guyanese and Guyanese expatriates living in other countries.[154]

In December 2018, the government had been defeated by a

Disputed elections, ethnic conflict, and territorial disputes

In August 2020, the 75-year-old incumbent David Granger lost narrowly and he did not accept the result.

In September 2020, after the election, Nafeeza Yahya-Sakur and Anatoly Kurmanaev of the

Following the discovery of oil reserves in

The referendum's questions were condemned by the Guyanese government,[170] the Commonwealth of Nations Secretary-General Patricia Scotland,[171] and Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), Luis Almagro.[172] Also, the leadership of the Caribbean Community voiced support for Guyana,[173] and Brazil increased its military presence along its northern border, in response to the escalating tensions in the region.[174] Within Venezuela, the Episcopal Conference of Venezuela called for resolving the conflict between Guyana and Venezuela peacefully,[175][176] and the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV) described the referendum as the "old strategy of the bourgeoisie [that tries] to instill patriotic and chauvinist feelings in a good part of the population (...) making people believe that in our country there is no more important problem to solve".[177] Some speculated that the dispute has "raised fears of US intervention in the region" due to U.S. backing of the Guyanese government.[178]

See also

- British colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of the Americas

- History of the British West Indies

- History of South America

- History of the Caribbean

- Politics of Guyana

- List of governors of British Guiana

- List of governors-general of Guyana

- List of presidents of Guyana

- List of prime ministers of Guyana

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

References

- ^ ISBN 0-7230-1005-6.

- ^ S2CID 247587603. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 4.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Guyana". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on June 19, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ CARICOM. Archivedfrom the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bocinski, Jessica (November 3, 2021). "Guyana: An Introduction". This Land Is Your Land. Chapman University. Archived from the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 6.

- ^ Thompson 1991, pp. 13.

- ^ a b c d "The forgotten history of Dutch slavery in Guyana". Leiden University. February 26, 2020. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Thompson 1991, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Thompson 1991, pp. 14–15, 18, 20.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1993, pp. 7.

- ^ Kreeke, Frank van de (2013). Essequebo en Demerary, 1741-1781: beginfase van de Britse overname (PDF) (Masters). Leiden University. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Shameerudeen 2020, pp. 149.

- ^ "History of Georgetown". M&CC Georgetown, Guyana. 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1993, pp. 9.

- ^ a b Thompson 1991, pp. 19.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 151.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 150.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 152.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1993, pp. 10.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 10–11.

- ^ "Award regarding the Boundary between the Colony of British Guiana and the United States of Venezuela" (PDF). United Nations. October 3, 1899. pp. 331–340. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2023.

- ^ a b "Border Controversy between Guyana and Venezuela". Political and Peacebuilding Affairs. United Nations. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Arbitral Award of 3 October 1899 (Guyana v. Venezuela)". International Court of Justice. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Singh, Yvonne (April 16, 2019). "How Scotland erased Guyana from its past". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Révauger 2008, pp. 105–106.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Ward 1991, pp. 81.

- ^ Ward 1991, pp. 85.

- ^ Shameerudeen 2020, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Shameerudeen 2020, pp. 146.

- ^ Mangru, Basdeo (April 1986). "Indian Labour in British Guiana". History Today. 36 (4). Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1993, pp. 11.

- ^ "History Of the Guyana Police Force". Guyana Police Force. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 101.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 1993, pp. 13.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "British Guiana (1928-1966)". University of Central Arkansas. Archived from the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ MacDonald 1993, pp. 14–15.

- ^ "History of Rice in Guyana". Guyana Rice Development Board. 14 September 2016. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 104–105.

- JSTOR 27861568.

- ^ a b c d e Curry, Mary E. (February 3, 2022). "The Walter Rodney Murder Mystery in Guyana 40 Years Later". Briefing Book # 784. National Security Archive. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Prados, John; Jimenez-Bacardi, Arturo (April 6, 2020). "CIA Covert Operations: The 1964 Overthrow of Cheddi Jagan in British Guiana". Briefing Book # 700. National Security Archive. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Foreign Policy. Archivedfrom the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- University of Maryland Center for International Development and Conflict Management. Archivedfrom the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Black 2005, pp. 153.

- Parliament of Guyana. pp. 45–46. Archived(PDF) from the original on January 1, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Former Deputy Prime Minister Brindley Benn dies at 86". Guyana Chronicle. December 12, 2009. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- People's Progressive Party. Archived from the originalon July 7, 2006. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Remembering Janet Jagan". Cheddi Jagan Research Centre. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Wilson Center. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "MI5 files reveal details of 1953 coup that overthrew British Guiana's leaders". The Guardian. Associated Press. August 25, 2011. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ . Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- U.S. State Department. 2008. Archivedfrom the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Guyanese President Cheddi Jagan dies". CNN. 6 March 1997. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Bahadur, Gaiutra (October 30, 2020). "In 1953, Britain openly removed an elected government, with tragic consequences | Gaiutra Bahadur". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Blum 2000, pp. 133, 171.

- ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- JSTOR 20668810. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-135-20515-7.

- JSTOR 165891. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Long, William R. (August 7, 1985). "Guyana's President Burnham Dies at 62". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Palash R., Ghosh (28 November 2011). "Guyana Elections Expected to Break Down According to Racial Lines". International Business Times. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- JSTOR 40393870.

- ^ David J. Carroll; Robert A. Pastor (June 1993). Moderating Ethnic Tensions by Electoral Mediation (PDF) (Report). Carter Center. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Biography of Dr. Cheddi Jagan". Cheddi Jagan Research Centre. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Government Publishing Office. p. iv. Archived from the original(PDF) on April 24, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Paris, France: Spokesman Books.Excerpts

- ISBN 978-92-3-103359-9.

- New York Times. June 16, 1964. Archivedfrom the original on November 3, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- JSTOR 20668810. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- S2CID 154080206. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-64259-678-6.

- ^ Blum 2000, pp. 133, 171, 296.

- ^ "Brief History". Bank of Guyana. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "History of Parliament". Parliament of the Co-Operative Republic of Guyana. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Guyana country profile". BBC News. October 2012. Archived from the original on March 16, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Raúl Leoni paró en seco a Guyana en la Isla Anacoco (documento)". La Patilla. September 26, 2011. Archived from the original on December 2, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8419-0961-8.

- ^ "Ankoko Island". Hansard 1803-2005. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on July 12, 2023. HC Deb 22 October 1968 vol 770 cc1075-6

- Department of State. Archivedfrom the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Guyana: History of Lending Commitments as of April 30, 2003". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-000-30689-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4931-2655-2.

- ^ Briceño Monzón, Claudio A.; Olivar, José Alberto; Buttó, Luis Alberto (2016). La Cuestión Esequibo: Memoria y Soberanía. Caracas, Venezuela: Universidad Metropolitana. p. 145.

- ^ GONZÁLEZ, Pedro. La Reclamación de la Guayana Esequiba. Caracas: Miguel A. García e hijo S.R.L. 1991.

- ^ "Guyana: De Rupununi a La Haya" [Guyana: From Rupununi to The Hague]. En El Tapete (in Spanish). 4 July 2020. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ González, Pedro (1991). La Reclamación de la Guayana Esequiba. Caracas.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "President Granger reissues book on the Rupununi Rebellion of 1969". Office of the President of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana. January 17, 2019. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "The State under Burnham". Guyana Times International. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Moves of Nonaligned Countries". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan). Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "About Guyana". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Cooperative Republic of Guyana. January 3, 2014. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-78533-993-6.

- ^ "The Guyana National Service". Stabroek News. December 10, 2008. Archived from the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "History". High Commission of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana in South Africa. Archived from the original on May 7, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- S2CID 145724717.

- ^ "Working People's Alliance (WPA)". Archives Research Center. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Guyanese sugar workers strike 135 days for economic justice, 1977", Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College, January 31, 2011, archived from the original on October 26, 2021, retrieved July 12, 2023

- ^ Ishmael, Odeen (April 2006). "The Rigged Referendum of 1978". Guyana Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ "Guyana, 10 July 1978: Constitutional amendments of the Parliament". Direct Democracy (in German). 10 July 1978. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023.

- ^ Nohlen, p365

- ^ Kinzer 2006, pp. 226.

- ^ Rolling Stone. Archivedfrom the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on January 4, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Grainger, Sarah (November 18, 2011). "Jonestown: Guyana ponders massacre site's future". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 23, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

We don't want to bring back the association with Jonestown and tragedy," Mr Haralsingh says. "So it's not our priority.

- ^ Conray, J. Oliver (November 17, 2018). "An apocalyptic cult, 900 dead: remembering the Jonestown massacre, 40 years on". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Effron, Lauren; Delarosa, Monica (September 26, 2018). "40 years after Jonestown massacre, ex-members describe Jim Jones as a 'real monster'". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- History.com. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Jonestown". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- History.com. April 19, 2022. Archivedfrom the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- Rolling Stone. Archivedfrom the original on June 14, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Jonestown". FBI Records: The Vault. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Scheeres, Julia (November 19, 2021). "Jonestown: How Jim Jones Betrayed All His Followers". Newsweek. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- Washington Post. Archivedfrom the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Merrill, Tim (1993). "Introduction". In Merrill, Tim (ed.). Guyana and Belize: country studies (PDF) (second ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress Federal Research Division. p. xx. ALT URL

- ^ Report of the Commission of Inquiry Appointed to Enquire and Report on the Circumstances Surrounding the Death in an Explosion of the Late Dr. Walter Rodnsey on the Thirteenth Day of Jone, One Thousand Nine Hundred and Eighty in Georgetown. Atlanta University Center (Report). Commission of Inquiry. 2014. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- UPI. Archivedfrom the original on July 12, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Blum 2000, pp. 133.

- ^ Hayword, Susanna (May 28, 1989). "Guyana Has Gold, Diamonds and Poverty: Despite Rich Natural Resources, Country's Economy Is in Shambles". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 13, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-58367-151-1.

- ^ Kinzer 2006, pp. 223.

- Washington Post. Archivedfrom the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- U.S. State Department. Archivedfrom the original on June 19, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Hollis 2005, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Guyana (PDF) (Report). Inter-Parliamentary Union. pp. 1–2. Chron. XX (1985-1986). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ U.S. State Department. 2022. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Downes, Andrew S. (1993). "Structural Adjustment Policies in the Caribbean". La Educación. 116 (3). Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- S2CID 261960655. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Philippe Egoumé-Bossogo; Ebrima Faal; Raj Nallari; Ethan Weisman (March 19, 2003). "Introduction and Background". Guyana: Experience with Macroeconomic Stabilization, Structural Adjustment,and Poverty Reduction (Report). International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Meeker-Lowry, Susan (Summer 1995). "Guyana Takes On The IMF". Context Institute. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Hollis 2005, pp. 112–117.

- ^ "Guyana / Guyana". Political Database of the Americas. Georgetown University. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-888777-92-5.

- ^ "Curbing electoral violence in Guyana". Centre for Public Impact. March 27, 2016. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Good Hope Canal releasing water from EDWC". Stabroek News. December 29, 2016. Archived from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "UNASUR indifference to Guyana". Guyana Chronicle. December 8, 2016. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "History". Embassy of Guyana in Brussels. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Guyana governing party's Donald Ramotar wins presidency". BBC News. December 2, 2021. Archived from the original on February 6, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (November 7, 2021). "Guyana is a poor country that was a green champion. Then Exxon discovered oil". NPR. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Nte, Oluka, Feartherstone, "Small States, Statescraft and the Challenges of National Security: The Case of Guyana", 93

- ^ "Guyana". ExxonMobil. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- The World Bank Group. Archivedfrom the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Ex-general David Granger wins Guyana election". BBC News. May 15, 2021. Archived from the original on February 6, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Granger sworn in as President". Stabroek News. May 16, 2015. Archived from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Noel, Melissa (May 27, 2016). "Guyana Jubilee: Celebrating 50 Years of Independence". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Guyana swears in Irfaan Ali as president after long stand-off". BBC News. August 3, 2020. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Guyana turns attention to racism". BBCCaribbean.com. BBC News. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Hookumchand, Gabrielle; Seenarine, Moses (May 8, 2000). "Conflict between East Indians and Blacks". Guyana News and Information. Archived from the original on August 1, 2005. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "Essequibo: Venezuelans vote to claim Guyana-controlled oil region". BBC News. 2023-12-04. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ "FOTOS | Se registra poca afluencia de electores en el referendo no vinculante sobre el Esequibo". Monitoreamos. 2023-12-03.

- ^ "Referéndum consultivo comienza con una escasa afluencia de electores en los centros". Runrunes. 2023-12-03.

- ^ "Poca afluencia de venezolanos en el referendo del Esequibo convocado por Maduro". ABC. 2023-12-03.

- ^ "Poca afluencia de votantes domina el referendo por el Esequibo". Diario Las Américas. 2023-12-03.

- ^ "Capriles cifra en 89,8% la abstención en el referendo sobre disputa con Guyana". El Nacional (in Spanish). 4 December 2023.

- Swissinfo(in Spanish). 2023-12-04. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ Shortell, David (December 4, 2023). "Venezuelans approve takeover of oil-rich region of Guyana in referendum". CNN. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- Venezuela Analysis. Archivedfrom the original on November 26, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- Venezuela Analysis. Archivedfrom the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "Guyana Summons Venezuelan Ambassador In Border Spat". Barrons. AFP-Agence France Presse. 24 September 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Statement by the Commonwealth Secretary-General on the escalation of the Guyana-Venezuela border dispute". Commonwealth. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ Peralta, Patricio (27 October 2023). "Crece tensión entre Guyana y Venezuela por cuestionado referendo sobre el Esequibo". France 24. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ "Caricom urges respect for international law". Jamaica Observer. 2023-10-26. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ "Brazil increases northern border military presence amid Venezuela-Guyana spat -ministry". Reuters. 29 November 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Rodríguez Rosas, Ronny (2023-11-24). "Obispos piden "no manipular" con referendo del Esequibo". Efecto Cocuyo. Retrieved 2023-12-03.

- ^ "Obispos de Venezuela: No manipular el referéndum con fines políticos o de presión". Vatican News. 2023-11-23. Retrieved 2023-12-03.

- ^ "PCV se pronunció ante el referendo consultivo sobre el territorio Esequibo". Aporrea. 28 November 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- Venezuela Analysis. December 4, 2023. Archivedfrom the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

Sources

- Black, Jeremy, ed. (2005). World History Atlas: Mapping the Human Journey (second ed.). ISBN 978-1-4053-0267-8.

- ISBN 978-1-56751-195-6.

- Hollis, France (2005). "Continunity or Change: Structural Adjustment Decision-Making in Guyana (1988-1997) The Hoyte and Jagan Years". JSTOR 27866406.

- Kinzer, Stephen (2006). "Our Days of Weakness are Over". Overthrow: America's History of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq (first ed.). ISBN 978-0-8050-7861-9.

- MacDonald, Scott (1993). "Guyana Historical Setting". In Merrill, Tim (ed.). Guyana and Belize: country studies (PDF) (second ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress Federal Research Division. ALT URL

- ISBN 978-2-13-057110-0. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Shameerudeen, Clifmond (2020). "Christian History of East Indians of Guyana". Journal of Adventist Mission Studies. 16 (2): 146–171. . Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Thompson, Alvin O. (1991). "Amerindian-European Relations in Dutch Guyana". In Beckles, Hilary; Shepard, Verene (eds.). Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (first ed.). New York: ISBN 1-56584-086-0.

- Ward, J.R. (1991). "The Profitability of Sugar Planting in the British West Indies". In Beckles, Hilary; Shepard, Verene (eds.). Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (first ed.). New York: ISBN 1-56584-086-0.

Further reading

- Aneiza Ali, Grace, ed. (2020). Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora. OBP collection. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 979-10-365-6515-1. EAN9791036565151.

- Calix, Jasmine Jennilee (2008). Eeconomic and Societal Effects of Structural Adjustment in Guyana (PDF) (Masters). University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Daly, Vere T. (1974). The Making of Guyana. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-14482-4. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Daly, Vere T. (1975). A Short History of The Guyanese People. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-18304-5. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Henry, Paget; Stone, Carl (1983). The Newer Caribbean: Decolonization, Democracy, and Development. Volume 4 of Inter-American politics series. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues. ISBN 0-89727-049-5. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Hoonhout, Bram (2022). Borderless Empire: Dutch Guiana in the Atlantic World, 1750–1800. Georgia: ISBN 9-780-8203-6258-8.

- Hope, Kempe Ronald (1985). Guyana: Politics and Development in an Emergent Socialist State. Oakville, Ont: Mosaic Press. ISBN 0-88962-302-3. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2006). U.S. Intervention in British Guiana: A Cold War Story. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5639-0. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Ross, Ivan A. (2021). The Cultural and Political History of Guyana: President John F. Kennedy's Interference in the Country's Democracy. Bloomington, Indiana: Archway Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6657-0938-5. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Spinner, Thomas J. (1984). A Political and Social History of Guyana, 1945–1983. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-852-2. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Sued-Badillo, Jalil, ed. (2003). General History of the Caribbean: Volume I: Autochthonous Societies. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 0-333-72453-4.