History of Iraq

| History of Iraq |

|---|

|

|

|

Iraq during antiquity witnessed some of the world's earliest

This era of self-rule lasted until 539 BC, when the

Over the next 700 years, the regions forming modern Iraq came under

Ottoman rule ended with World War I, after which the

Prehistory

During 1957–1961 Shanidar Cave was excavated by Ralph Solecki and his team from Columbia University, and nine skeletons of Neanderthal man of varying ages and states of preservation and completeness (labelled Shanidar I–IX) were discovered dating from 60,000 to 80,000 years BP. A tenth individual was recently discovered by M. Zeder during examination of a faunal assemblage from the site at the Smithsonian Institution. The remains seemed to Zeder to suggest that Neanderthals had funeral ceremonies, burying their dead with flowers (although the flowers are now thought to be a modern contaminant), and that they took care of injured and elderly individuals.

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops and the development of cursive script, Mathematics, Astronomy and Agriculture."[6]

Ancient Mesopotamia

Bronze Age

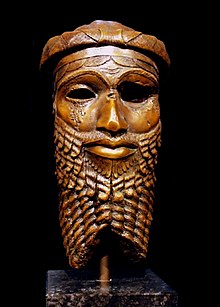

The north of Mesopotamia had become the Akkadian-speaking state of Assyria by the late 25th century BC. Along with the rest of Mesopotamia it was ruled by Akkadian kings from the late 24th to mid 22nd centuries BC, after which it once again became independent.[7]

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC,[9] but Sumerian continued to be used as a written or ceremonial language in Mesopotamia well into the period of classical antiquity.

Babylonia emerged from the Amorite dynasties (c. 1900 BC) when Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BC), unified the territories of the former kingdoms of Sumer and Akkad. During the early centuries of what is called the "Amorite period", the most powerful city-states were Isin and

Assyria was an Akkadian (East Semitic) kingdom in Upper Mesopotamia, that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur (Akkadian Aššūrāyu).

Of the early history of the kingdom of Assyria, little is positively known. In the

Assyria had a period of empire from the 19th to 18th centuries BC. From the 14th to 11th centuries BC Assyria once more became a major power with the rise of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

Iron Age

The

The

The Neo-Babylonian period ended with the reign of Nabonidus in 539 BC. To the east, the Persians had been growing in strength, and eventually Cyrus the Great established his dominion over Babylon.

-

The Assyrian Empire at its greatest extent

-

The Neo-Babylonian Empire at its greatest extent

Classical Antiquity

Achaemenid and Seleucid rule

Mesopotamia was conquered by the Achaemenid Persians under Cyrus the Great in 539 BC, and remained under Persian rule for two centuries.

The Persian Empire fell to

Parthian and Roman rule

At the beginning of the 2nd century AD, the Romans, led by emperor Trajan, invaded Parthia and conquered Mesopotamia, making it an imperial province. It was returned to the Parthians shortly after by Trajan's successor, Hadrian.

Sassanid Empire

In the 3rd century AD, the Parthians were in turn succeeded by the

and Lower Media. The term Iraq is widely used in the medieval Arabic sources for the area in the center and south of the modern republic as a geographic rather than a political term, implying no greater precision of boundaries than the term "Mesopotamia" or, indeed, many of the names of modern states before the 20th century.There was a substantial influx of Arabs in the Sassanid period.

Until 602, the desert frontier of the Persian Empire had been guarded by the Arab

Middle Ages

Islamic conquest

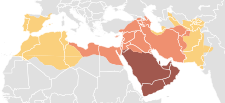

The first organized conflict between invading Arab tribes and occupying Persian forces in Mesopotamia seems to have been in 634, when the Arabs were defeated at the Battle of the Bridge. There was a force of some 5,000

The Islamic expansions constituted the largest of the Semitic expansions in history. These new arrivals did not disperse and settle throughout the country; instead they established two new garrison cities, at

Abbasid Caliphate

The city of Baghdad was built in the 8th century and became the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate. Baghdad soon became the primary cultural center of the Muslim world during the centuries of the incipient "Islamic Golden Age" of the 8th to 9th centuries.

In the 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate entered a period of decline. During the late 9th to early 11th centuries, a period known as the "

Mongol invasion

In the later 11th century, Iraq fell under the rule of the

Turco-Mongol rule

Iraq now became a province on the southwestern fringes of the Ilkhanate and Baghdad would never regain its former importance.

The

Ottoman and Mamluk rule

During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Qara Qoyunlu or Black Sheep Turkmens ruled the area now known as Iraq. In 1466, the Aq Qoyunlu or White Sheep defeated the Qara Qoyunlu and took control. Later, the Aq Qoyunlu were defeated by the Safavid dynasty, who took control over Mesopotamia for some time and asserted their hegemony over Iraq in the periods 1508–1533, ending with the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555), and 1622–1638, ending with the Ottoman–Safavid War (1623–1639).

In the 16th century, most of the territory of present-day Iraq came under the control of

- Mosul Province

- Baghdad Province

- Basra Province

During the years 1747–1831, Iraq was ruled by

20th century

British mandate of Mesopotamia

Ottoman rule over Iraq lasted until

Britain imposed a

Although the monarch

Independent Kingdom of Iraq

Establishment of Arab Sunni domination in Iraq was followed by Assyrian, Yazidi and Shi'a unrests, which were all brutally suppressed. In 1936, the first military coup took place in the Kingdom of Iraq, as Bakr Sidqi succeeded in replacing the acting Prime Minister with his associate. Multiple coups followed in a period of political instability, peaking in 1941.

During

In 1945, Iraq joined the United Nations and became a founding member of the Arab League. At the same time, the Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani led a rebellion against the central government in Baghdad. After the failure of the uprising, Barzani and his followers fled to the Soviet Union.

In 1948, massive violent protests known as the Al-Wathbah uprising broke out across Baghdad with partial communist support, having demands against the government's treaty with Britain. Protests continued into spring and were interrupted in May when martial law was enforced as Iraq entered the failed 1948 Arab–Israeli War along with other Arab League members.

In February 1958, King

Republic of Iraq

Inspired by

Qasim's vision of nationalism involved the recognition of an Iraqi identity stemming from ancient Mesopotamia including its civilizations of Sumer, Akkad, Babylonia and Assyria.[24]

In 1961, Kuwait gained independence from Britain and Iraq claimed sovereignty over Kuwait. A period of considerable instability followed.

The same year,

Ba'athist Iraq

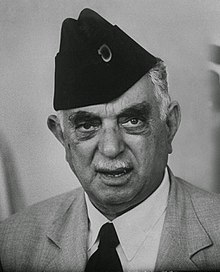

Qāsim was assassinated in February 1963, when the Ba'ath Party took power under the leadership of General Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr (prime minister) and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif (president). In June 1963, Syria, which by then had also fallen under Ba'athist rule, took part in the Iraqi military campaign against the Kurds by providing aircraft, armoured vehicles and a force of 6,000 soldiers. Several months later, `Abd as-Salam Muhammad `Arif led a successful coup against the Ba'ath government. Arif declared a ceasefire in February 1964 which provoked a split among Kurdish urban radicals on one hand and Peshmerga (Freedom fighters) forces led by Barzani on the other.

On April 13, 1966, President Abdul Salam Arif died in a helicopter crash and was succeeded by his brother, General

In the aftermath of the

Under Saddam Hussein

In July 1979, President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr was forced to resign by Saddam Hussein, who assumed the offices of both President and Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. Saddam then purged his opponents including those from within the Baath party.

- Iraq's Territorial Claims to Neighboring Countries

Iraq's territorial claims to neighboring countries were largely due to the plans and promises of the

Territorial disputes with

The war began when Iraq invaded Iran, launching a simultaneous invasion by air and land into Iranian territory on 22 September 1980, following a long history of

The war came at a great cost in lives and economic damage—half a million Iraqi and Iranian soldiers, as well as civilians, are believed to have died in the war with many more injured—but it brought neither reparations nor change in borders. The conflict is often compared to

A long-standing territorial dispute was the ostensible reason for Iraq's

In March 1991 revolts in the

On 6 August 1990, after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the U.N. Security Council adopted

The effects of the sanctions on the civilian population of Iraq have been disputed.

Iraqi cooperation with UN weapons inspection teams was questioned on several occasions during the 1990s.

U.S. invasion and the aftermath (2003–present)

2003 U.S. invasion

After the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington in the United States in 2001 were linked to the group formed by the multi-millionaire Saudi Osama bin Laden, American foreign policy began to call for the removal of the Ba'ath government in Iraq. Neoconservative think-tanks in Washington had for years been urging regime change in Baghdad. On August 14, 1998, President Clinton signed Public Law 105–235, which declared that ‘‘the Government of Iraq is in material and unacceptable breach of its international obligations.’’ It urged the President ‘‘to take appropriate action, in accordance with the Constitution and relevant laws of the United States, to bring Iraq into compliance with its international obligations.’’ Several months later, Congress enacted the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998 on October 31, 1998. This law stated that it "should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime." It was passed 360 - 38 by the United States House of Representatives and 99–0 by the United States Senate in 1998.

The US urged the

In March 2003, the United States and the United Kingdom, with military aid from other nations, invaded Iraq.

Over the following years in the

Occupation (2003–11)

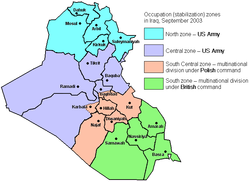

In 2003, after the American and British invasion, Iraq was occupied by U.S.-led

Terrorism emerged as a threat to Iraq's people not long after the invasion of 2003.

Reported acts of violence conducted by an uneasy tapestry of insurgents steadily increased by the end of 2006.

Insurgency and war (2011–2017)

The

The

On 30 April 2016,

Continued ISIL insurgency and protests (2017–present)

By 2018, violence in Iraq was at its lowest level in ten years.[54]

In November 2021, Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi survived a failed assassination attempt.[56]

Cleric Muqtada al-Sadr's

In October 2022, Abdul Latif Rashid was elected as the new President of Iraq after winning the parliamentary election against incumbent Barham Salih, who was running for a second term. The presidency is largely ceremonial and is traditionally held by a Kurd.[59] On 27 October 2022, Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, close ally of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, took the office to succeed Mustafa al-Kadhimi as new Prime Minister of Iraq.[60]

See also

References

- ^ "Baghdad's Treasure: Lost To The Ages", Time, 28 April 2003, archived from the original on March 7, 2008, retrieved 4 May 2010

- )

- ^ D. Gershon Lewental, "QĀDESIYA, BATTLE OF," Encyclopædia Iranica Online, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/qadesiya-battle Archived 2020-10-04 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on 21 July 2014).

- ISBN 978-1576071861.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian.

- ^ Milton-Edwards, Beverley (May 2003). "Iraq, past, present and future: a thoroughly-modern mandate?". History & Policy. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b George Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ^ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ^ [Woods C. 2006 "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S.L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91–120 Chicago [1] Archived 2013-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Assyrian King Listand Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, p. 187.

- ^ Aberbach 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Düring 2020, p. 133.

- ^ "Black Obelisk, K. C. Hanson's Collection of Mesopotamian Documents". K.C. Hansen. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-534-62164-3.

The Greco-Macedonian Elite. The Seleucids respected the cultural and religious sensibilities of their subjects but preferred to rely on Greek or Macedonian soldiers and administrators for the day-to-day business of governing. The Greek population of the cities, reinforced until the second century BCE by immigration from Greece, formed a dominant, although not especially cohesive, elite.

- OCLC 585939.

In addition to the court and the army, Syrian cities were full of Greek businessmen, many of them pure Greeks from Greece. The senior posts in the civil service were also held by Greeks. Although the Ptolemies and the Seleucids were perpetual rivals, both dynasties were Greek and ruled by means of Greek officials and Greek soldiers. Both governments made great efforts to attract immigrants from Greece, thereby adding yet another racial element to the population.

- name of Iraq.

- ^ Thomas T. Allsen Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia, p.84

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 132–135.

- ^ Bayne Fisher, William "The Cambridge History of Iran", p.3: "(From then until the Timur's invasion of the country, Iran was under the rule of various rival petty princes of whom henceforth only the Jalayirids could claim Mongol)

- ^ The History Files Rulers of Persia Archived 2021-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Iraq. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 October 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online Archived 2007-12-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "How Mesopotamia Became Iraq (and Why It Matters)". Los Angeles Times. 1990-09-02. Archived from the original on 2022-10-05. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ISBN 9781841769912.

- ^ Reich, Bernard. Political leaders of the contemporary Middle East and North Africa: A Bibliographical Dictionary. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press, Ltd, 1990. Pp. 245.

- ^ G.S. Harris, Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, pp.118–120, 1977

- ^ "Introduction : GENOCIDE IN IRAQ: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds (Human Rights Watch Report, 1993)". Hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ Tyler, Patrick E. "Officers Say U.S. Aided Iraq in War Despite Use of Gas" Archived 2017-06-30 at the Wayback Machine New York Times August 18, 2002.

- ^ a b Molavi, Afshin (2005). "The Soul of Iran". Norton: 152.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fathi, Nazila (14 March 2003). "Threats And Responses: Briefly Noted; Iran-Iraq Prisoner Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge, 2008, p.171

- ^ Findlay, Justin (6 October 2017). "What Was Operation Desert Storm?". WorldAtlas. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "UN Security Council Resolution 687 -1991". www.mideastweb.org. Archived from the original on 2018-05-12. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ Iraq surveys show 'humanitarian emergency' Archived 2009-08-06 at the Wayback Machine UNICEF Newsline August 12, 1999

- ^ Rubin, Michael (December 2001). "Sanctions on Iraq: A Valid Anti-American Grievance?". 5 (4). Middle East Review of International Affairs: 100–115. Archived from the original on 2012-10-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Significance. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- PMID 29225933.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein said sanctions killed 500,000 children. That was 'a spectacular lie.'". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-08-04. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ^ Richard Butler, Saddam Defiant, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2000, p. 224

- ^ Timeline–Rise, fall and spread of the Islamic State, archived from the original on February 8, 2021, retrieved December 14, 2020

- nytimes.com. Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Ibrahim, Ellen Knickmeyer and K. I. (23 February 2006). "Bombing Shatters Mosque In Iraq". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Logan, Joseph (December 18, 2011). "Last U.S. troops leave Iraq, ending war". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ "John Kerry holds talks in Iraq as more cities fall to ISIS militants". CNN. 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Al Qaeda-linked militants capture Fallujah during violent outbreak". Fox News. 4 January 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Militants kill 21 Iraqi leaders, capture 2 border crossings". NY Daily News. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Iraq Update #42: Al-Qaeda in Iraq Patrols Fallujah; Aims for Ramadi, Mosul, Baghdad". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ "Isis seizes Ramadi". The Independent. May 18, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Iraq: Shiite Gov't faces Mammoth Task in taking Sunni al-Anbar from ISIL". Informed Comment. 19 April 2015. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Islamic State overruns Camp Speicher, routs Iraqi forces". Long War Journal. 19 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Insurgents in Iraq Overrun Mosul Provincial Government Headquarters". Voanews.com. Reuters. 2014-06-09. Archived from the original on 2015-12-26. Retrieved 2014-07-31. "Iraqi city of Mosul falls to jihadists". CBS. 10 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Mostafa, Nehal (9 December 2017). "Iraq announces end of war against IS, liberation of borders with Syria: Abadi". Iraqi News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Thousands of protesters storm Iraq parliament green zone". AFP. 16 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Violence in Iraq at Lowest Level in 10 years". Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Alkhshali, Hamdi; Tawfeeq, Mohammed; Qiblawi, Tamara (5 October 2019). "Iraq Prime Minister calls protesters' demands 'righteous,' as 93 killed in demonstrations". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Iraq PM says his would-be assassins have been identified". BBC News. 8 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Iraq's Surprise Election Results". Crisis Group. 16 November 2021. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Iraqi leaders vow to move ahead after dozens quit parliament". The Independent. 2022-06-13. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ National, The (14 October 2022). "Who are Iraq's new president Abdul Latif Rashid and PM nominee Mohammed Shia Al Sudani?". The National. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Iraq gets a new government after a year of deadlock – DW – 10/28/2022". dw.com. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

Sources

- Aberbach, David (2003). Major Turning Points in Jewish Intellectual History. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1403917669.

- Düring, Bleda S. (2020). The Imperialisation of Assyria: An Archaeological Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108478748.

Further reading

- Broich, John. Blood, Oil and the Axis: The Allied Resistance Against a Fascist State in Iraq and the Levant, 1941 (Abrams, 2019).

- de Gaury, Gerald. Three Kings in Baghdad: The Tragedy of Iraq's Monarchy, (IB Taurus, 2008). ISBN 978-1-84511-535-7

- Elliot, Matthew. Independent Iraq: British Influence from 1941 to 1958 (IB Tauris, 1996).

- Fattah, Hala Mundhir, and Frank Caso. A brief history of Iraq (Infobase Publishing, 2009).

- Franzén, Johan. "Development vs. Reform: Attempts at Modernisation during the Twilight of British Influence in Iraq, 1946–1958," Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37#1 (2009), pp. 77–98

- Kriwaczek, Paul. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Atlantic Books (2010). ISBN 978-1-84887-157-1

- Murray, Williamson, and Kevin M. Woods. The Iran-Iraq War: A military and strategic history (Cambridge UP, 2014).

- Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books (1992). ISBN 0-14-012523-X

- Silverfarb, Daniel. Britain's informal empire in the Middle East: a case study of Iraq, 1929-1941 ( Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Silverfarb, Daniel. The twilight of British ascendancy in the Middle East: a case study of Iraq, 1941-1950 (1994)

- Silverfarb, Daniel. "The revision of Iraq's oil concession, 1949–52." Middle Eastern Studies 32.1 (1996): 69-95.

- Simons, Geoff. Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam (Springer, 2016).

- Tarbush, Mohammad A. The role of the military in politics: A case study of Iraq to 1941 (Routledge, 2015).

- Tripp, Charles R. H. (2007). A History of Iraq 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press.

Historiography

- Bashkin, Orit (2015). "Deconstructing Destruction: The Second Gulf War and the New Historiography of Twentieth-Century Iraq". The Arab Studies Journal. 23 (1): 210–234. JSTOR 44744905.