History of Jerusalem

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

| History of Israel | |

|---|---|

| |

| 538–333 BCE | |

| Hellenistic period | 333–164 BCE |

| Hasmonean dynasty | 164–37 BCE |

| Herodian dynasty | 37 BCE–6 CE |

| Roman Judaea

Jewish-Roman Wars ) | 6 CE–136 CE |

During its long history,

Given the city's central position in both

Ancient period

Proto-Canaanite period

Archaeological evidence suggests that the first settlement was established near

Canaanite and Egyptian period

Archaeological evidence suggests that by the 17th century BCE, the

By c. 1550–1400 BCE, Jerusalem had become a vassal to Egypt after the Egyptian

The power of the Egyptians in the region began to decline in the 12th century BCE, during the

Israelite period

According to the Bible, the

Later, according to the biblical narrative, King

When the Kingdom of Judah split from the larger Kingdom of Israel (which the Bible places near the end of the reign of Solomon, c. 930 BCE, though Israel Finkelstein and others dispute the very existence of a unified monarchy to begin with[21]), Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Judah, while the Kingdom of Israel located its capital at Shechem in Samaria. Thomas L. Thompson argues that it only became a city and capable of acting as a state capital in the middle of the 7th century.[22] However, Omer Sergi argues that recent archaeological discoveries at the City of David and the Ophel seem to indicate that Jerusalem was already a significant city by the Iron Age IIA.[23]

Both the Bible and regional archaeological evidence suggest the region was politically unstable during the period 925–732 BCE. In 925 BCE, the region was invaded by Egyptian Pharaoh

The Bible records that shortly after this battle, Jerusalem was sacked by

Two decades later, most of Canaan including Jerusalem was conquered by

By the end of the First Temple Period, Jerusalem was the sole acting religious shrine in the kingdom and a centre of regular pilgrimage; a fact which archaeologists generally view as being corroborated by the evidence,[citation needed] though there remained a more personal cult involving Asherah figures, which are found spread throughout the land right up to the end of this era.[21]

Assyrian and Babylonian periods

Jerusalem was the capital of the Kingdom of Judah for some 400 years. It had survived an

The

Persian (Achaemenid) period

According to the Bible, and perhaps corroborated by the

During this period, Aramaic-inscribed "Yehud coinage" were produced – these are believed to have been minted in or near Jerusalem, although none of the coins bear a mint mark.

Classical antiquity

Hellenistic period

Ptolemaic and Seleucid province

When

Under the Seleucids many Jews had become

Hasmonean period

As a result of the Maccabean Revolt, Jerusalem became the capital of the autonomous and eventually independent Hasmonean state which lasted for over a century. After Judas' death, his brothers Jonathan Apphus and Simon Thassi were successful in creating and consolidating the state. They were succeeded by John Hyrcanus, Simon's son, who won independence, enlarged Judea's borders, and began minting coins. Hasmonean Judea became a kingdom and continued to expand under his sons kings Aristobulus I and subsequently Alexander Jannaeus. When his widow Salome Alexandra died in 67 BCE her sons Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II fought among themselves over who would succeed her. In order to resolve their dispute, the parties involved turned to Roman general Pompey, who paved the way for a Roman takeover of Judea.[27]

Pompey supported Hyrcanus II over his brother Aristobulus II who then controlled Jerusalem, and the city was soon under siege. Upon his victory, Pompey desecrated the Temple by entering the Holy of Holies, which could only be done by the High Priest. Hyrcanus II was restored as High Priest, stripped of his royal title but recognized as an ethnarch in 47 BCE. Judea remained an autonomous province but still with a significant amount of independence. The last Hasmonean king was Aristobulus' son, Antigonus II Matityahu.

Early Roman period

In 37 BCE,

Herod also built

In the 1st century CE, Jerusalem became the birthplace of

By the end of the Second Temple period, Jerusalem's size and population had reached a peak that would not be broken until the 20th century. There were about 70,000- 100,000 people living in the city at that time, according to modern estimations.[31]

Jewish–Roman Wars

In 66 CE, the Jewish population in the

Jerusalem was later re-founded and rebuilt as the

Late antiquity

Late Roman period

Aelia Capitolina of the Late Roman period was a

A Roman legionary tomb at Manahat, the remains of Roman villas at Ein Yael and Ramat Rachel, and the Tenth Legion's kilns found close to Giv'at Ram, all within the borders of modern-day Jerusalem, are all signs that the rural area surrounding Aelia Capitolina underwent a romanization process, with Roman citizens and Roman veterans settling in the area during the Late Roman period.[45] Jews were still banned from the city throughout the remainder of its time as a Roman province.

Byzantine period

Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire, Jerusalem prospered as a hub of Christian worship. After allegedly seeing a vision of a cross in the sky in 312,

In the Siege of Jerusalem of 614, after 21 days of relentless siege warfare, Jerusalem was captured. Byzantine chronicles relate that the Sassanids and Jews slaughtered tens of thousands of Christians in the city, many at the Mamilla Pool,[49][50] and destroyed their monuments and churches, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This episode has been the subject of much debate between historians.[51] The conquered city would remain in Sassanid hands for some fifteen years until the Byzantine emperor Heraclius reconquered it in 629.[52]

Medieval period

Early Muslim period

Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates

Jerusalem was one of the

Under the early centuries of Muslim rule, especially during the

The

Geographers

Fatimid period

The early Arab period was also one of religious tolerance.[

The Haram Area (Noble Sanctuary) lies in the eastern part of the city; and through the bazaar of this (quarter) you enter the Area by a great and beautiful gateway (Dargah)... After passing this gateway, you have on the right two great colonnades (Riwaq), each of which has nine-and-twenty marble pillars, whose capitals and bases are of colored marbles, and the joints are set in lead. Above the pillars rise arches, that are constructed, of masonry, without mortar or cement, and each arch is constructed of no more than five or six blocks of stone. These colonnades lead down to near the Maqsurah.[59]

Seljuk period

Under Az-Zahir's successor

In 1086, the Seljuk emir of Damascus, Tutush I, appointed Artuk Bey governor of Jerusalem. Artuk died in 1091, and his sons Sökmen and Ilghazi succeeded him. In August 1098, while the Seljuks were distracted by the arrival of the First Crusade in Syria, the Fatimids under vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah appeared before the city and laid siege to it. After six weeks, the Seljuk garrison capitulated and was allowed to leave for Damascus and Diyar Bakr. The Fatimid takeover was followed by the expulsion of most of the Sunnis, in which many of them were also killed.

Crusader/Ayyubid period

The time span consisting of the 12th and 13th centuries is sometimes referred to as the medieval period, or the Middle Ages, in the history of Jerusalem.[60]

First Crusader kingdom (1099–1187)

Fatimid control of Jerusalem ended when it was captured by

Christian settlers from the West set about rebuilding the principal shrines associated with the life of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was ambitiously rebuilt as a great Romanesque church, and Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount (the Dome of the Rock and the

Ayyubid control

The Kingdom of Jerusalem lasted until 1291; however, Jerusalem itself was recaptured by

In 1173

In 1243 Jerusalem came again into the power of the Christians, and the walls were repaired. The

Mamluk period

In 1250 a crisis within the Ayyubid state led to the rise of the Mamluks to power and a transition to the

Jerusalem was a significant site of

Jewish presence

Latin presence

The first provincial or superior of the Franciscan religious order, founded by Francis of Assisi, was Brother Elia from Assisi. In the year 1219 the founder himself visited the region in order to preach the Gospel to the Muslims, seen as brothers and not enemies. The mission resulted in a meeting with the sultan of Egypt, Malik al-Kamil, who was surprised by his unusual behaviour. The Franciscan Province of the East extended to Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, and the Holy Land. Before the taking over of Acre (on 18 May 1291), Franciscan friaries were present at Acre, Sidon, Antioch, Tripoli, Jaffa, and Jerusalem.[citation needed]

From

The friars, coming from any of the Order's provinces, under the jurisdiction of the father guardian (superior) of the monastery on Mount Zion, were present in Jerusalem, in the Cenacle, in the church of the

The monastery on Mount Zion was used by Brother Alberto da Sarteano for his papal mission for the union of the Oriental Christians (

In 1482, the visiting

Early modern period

Early Ottoman period

In 1516, Jerusalem was

Latin presence

In 1551 the Friars were expelled by the Turks[71] from the Cenacle and from their adjoining monastery. However, they were granted permission to purchase a Georgian monastery of nuns in the northwest quarter of the city, which became the new center of the Custody in Jerusalem and developed into the Latin Convent of Saint Saviour (known as Dayr al Ātīn دير الاتين دير اللاتين Arabic)[72]).[73]

Jewish presence

In 1700, Judah HeHasid led the largest organized group of Jewish immigrants to the Land of Israel in centuries. His disciples built the Hurva Synagogue, which served as the main synagogue in Jerusalem from the 18th century until 1948, when it was destroyed by the Arab Legion.[Note 6] The synagogue was rebuilt in 2010.

Local vs. central power

In response to the onerous taxation policies and military campaigns against the city's hinterland by the governor Mehmed Pasha Kurd Bayram, the notables of Jerusalem, allied with the local peasantry and Bedouin, rebelled against the Ottomans in what became known as the Naqib al-Ashraf revolt and took control of the city in 1703–1705 before an imperial army reestablished Ottoman authority there. The consequent loss of power of Jerusalem's al-Wafa'iya al-Husayni family, which led the rebellion, paved the way for the al-Husayni family becoming one of the city's leading families.[75][76] Thousands of Ottoman troops were garrisoned in Jerusalem in the aftermath of the revolt, which caused a decline in the local economy.[77]

Late modern period

Late Ottoman period

In the mid-19th century, with the decline of the Ottoman Empire, the city was a backwater, with a population that did not exceed 8,000. Nevertheless, it was, even then, an extremely heterogeneous city because of its significance to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The population was divided into four major communities – Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Armenian – and the first three of these could be further divided into countless subgroups, based on precise religious affiliation or country of origin. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was meticulously partitioned between the

At the time, the communities were located mainly around their primary shrines. The Muslim community surrounded the

Several changes with long-lasting effects on the city occurred in the mid-19th century: their implications can be felt today and lie at the root of the

By the 1860s, the city, with an area of only one square kilometer, was already overcrowded. Thus began the construction of the New City, the part of Jerusalem outside of the city walls. Seeking new areas to stake their claims, the Russian Orthodox Church began constructing a complex, now known as the

In 1882, around 150 Jewish families arrived in Jerusalem from Yemen. Initially they were not accepted by the Jews of Jerusalem and lived in destitute conditions supported by the Christians of the Swedish-American colony, who called them Gadites.[78] In 1884, the Yemenites moved into Silwan.

British Mandate period

The British were victorious over the Ottomans in the Middle East during

By the time General Allenby took Jerusalem from the Ottomans in 1917, the new city was a patchwork of neighborhoods and communities, each with a distinct ethnic character. This continued under British rule, as the New City of Jerusalem grew outside the old city walls, and the Old City of Jerusalem gradually emerged as little more than an impoverished older neighborhood.

The British had to deal with a conflicting demand that was rooted in Ottoman rule. Agreements for the supply of water, electricity, and the construction of a tramway system—all under concessions granted by the Ottoman authorities—had been signed by the city of Jerusalem and a Greek citizen, Euripides Mavromatis, on 27 January 1914. Work under these concessions had not begun and, by the end of the war the British occupying forces refused to recognize their validity. Mavromatis claimed that his concessions overlapped with the Auja Concession that the government had awarded to Rutenberg in 1921 and that he had been deprived of his legal rights. The Mavromatis concession, in effect despite earlier British attempts to abolish it, covered Jerusalem and other localities (e.g., Bethlehem) within a radius of 20 km (12 mi) around the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[82]

In 1922, the

On 29 November 1947, the

-

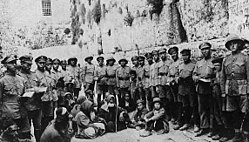

Jewish Legion soldiers at the Western Wall after taking part in 1917 British conquest of Jerusalem

-

Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem during 1944 British demolition of recent construction obscuring the historic city walls

-

Main residential areas of Jerusalem in 1947

-

The Jerusalem boundary in 1947 and the proposed boundary of a Corpus Separatum.

War and partition between Israel and Jordan (1948–1967)

1948 war

After partition, the fight for Jerusalem escalated, with heavy casualties among both fighters and civilians on the British, Jewish, and Arab sides. By the end of March 1948, just before the British withdrawal, and with the British increasingly reluctant to intervene, the roads to Jerusalem were cut off by Arab irregulars, placing the Jewish population of the city under siege. The siege was eventually broken, though massacres of civilians occurred on both sides,[citation needed] before the 1948 Arab–Israeli War began with the end of the British Mandate in May 1948.

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War led to massive displacement of Arab and Jewish populations. According to Benny Morris, due to mob and militia violence on both sides, 1,500 of the 3,500 (mostly ultra-Orthodox) Jews in the Old City evacuated to west Jerusalem as a unit.[87] See also Jewish Quarter. The comparatively populous Arab village of Lifta (today within the bounds of Jerusalem) was captured by Israeli troops in 1948, and its residents were loaded on trucks and taken to East Jerusalem.[87][88][89] The villages of Deir Yassin, Ein Karem and Malcha, as well as neighborhoods to the west of Jerusalem's Old City such as Talbiya, Katamon, Baka, Mamilla and Abu Tor, also came under Israeli control, and their residents were forcibly displaced;[citation needed] in some cases, as documented by Israeli historian Benny Morris and Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, among others, expulsions and massacres occurred.[87][90]

In May 1948 the US Consul,

Division between Jordan and Israel (1948–1967)

The

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Jerusalem was divided. The Western half of the New City became part of the newly formed state of Israel, while the eastern half, along with the Old City, was occupied by Jordan. According to David Guinn,

Concerning Jewish holy sites, Jordan breached its commitment to appoint a committee to discuss, among other topics, free access of Jews to the holy sites under its jurisdiction, mainly in the Western Wall and the important Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, as provided in the Article 8.2 of the Cease Fire Agreement between it and Israel dated April 3, 1949. Jordan permitted the paving of new roads in the cemetery, and tombstones were used for paving in Jordanian army camps. The Cave of Shimon the Just became a stable.[91]

According to Gerald M. Steinberg, Jordan ransacked 57 ancient synagogues, libraries and centers of religious study in the Old City Of Jerusalem, 12 were totally and deliberately destroyed. Those that remained standing were defaced, used for housing of both people and animals. Appeals were made to the United Nations and in the international community to declare the Old City to be an 'open city' and stop this destruction, but there was no response.[92] (See also Hurva Synagogue)

On 23 January 1950, the Knesset passed a resolution that stated Jerusalem was the capital of Israel.[citation needed]

State of Israel

Most Jews celebrated the event as a liberation of the city; a new Israeli holiday was created,

Under Israeli control, members of all religions are largely granted access to their holy sites. The major exceptions being security limitations placed on some Arabs from the West Bank and Gaza Strip from accessing holy sites due to their inadmissibility to Jerusalem, as well as limitations on Jews from visiting the Temple Mount due to both politically motivated restrictions (where they are allowed to walk on the Mount in small groups, but are forbidden to pray or study while there) and religious edicts that forbid Jews from trespassing on what may be the site of the Holy of the Holies. Concerns have been raised about possible attacks on the al-Aqsa Mosque after a serious arson attack on the mosque in 1969 (started by Denis Michael Rohan, an Australian fundamentalist Christian found by the court to be insane). Riots broke out following the opening of an exit in the Arab Quarter for the Western Wall Tunnel on the instructions of the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which prior Prime Minister Shimon Peres had instructed to be put on hold for the sake of peace (stating "it has waited for over 1000 years, it could wait a few more").

Conversely, Israeli and other Jews have showed concerns over excavations being done by the Waqf on the Temple Mount that could harm Temple relics, particularly excavations to the north of Solomon's Stables that were designed to create an emergency exit for them (having been pressured to do so by Israeli authorities).[94] Some Jewish sources allege that the Waqf's excavations in Solomon's Stables also seriously harmed the Southern Wall; however an earthquake in 2004 that damaged the eastern wall could also be to blame.

The status of East Jerusalem remains a

Since Israel gained control over East Jerusalem in 1967, Jewish settler organizations have sought to establish a Jewish presence in neighborhoods such as

See Jewish Quarter (Jerusalem).

Graphical overview of Jerusalem's historical periods (by rulers)

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "No city in the world, not even Athens or Rome, ever played as great a role in the life of a nation for so long a time, as Jerusalem has done in the life of the Jewish people."[4]

- ^ "For three thousand years, Jerusalem has been the center of Jewish hope and longing. No other city has played such a dominant role in the history, culture, religion and consciousness of a people as has Jerusalem in the life of Jewry and Judaism. Throughout centuries of exile, Jerusalem remained alive in the hearts of Jews everywhere as the focal point of Jewish history, the symbol of ancient glory, spiritual fulfillment and modern renewal. This heart and soul of the Jewish people engenders the thought that if you want one simple word to symbolize all of Jewish history, that word would be 'Jerusalem.'"[5]

- Arabic culture."[6]

- Canaanites before them. Acutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian history, the Palestinians saw themselves as the heirs of its rich associations."[7]

- ^ "When Judea was converted into a Roman province in 6 CE, Jerusalem ceased to be the administrative capital of the country. The Romans moved the governmental residence and military headquarters to Caesarea. The centre of government was thus removed from Jerusalem, and the administration became increasingly based on inhabitants of the Hellenistic cities (Sebaste, Caesarea and others)."[30]

- ^ "This was not done in the heat of battle, but by official order. Explosives were placed carefully and thoughtfully under the springing points of the domes, of the great Hurva synagogue."[74]

Citations

- ^ "Do We Divide the Holiest Holy City?". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.. According to Eric H. Cline's tally in Jerusalem Besieged.

- ^ "What is the oldest city in the world?". The Guardian. 16 February 2015.

- ^ a b Azmi Bishara. "A brief note on Jerusalem". Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ David Ben-Gurion, 1947

- ISBN 9780944029077.

- ^ Ali Qleibo, Palestinian anthropologist

- ^ Walid Khalidi, 1984, Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians, 1876–1948. Institute for Palestine Studies

- ^ Eric H. Cline. "How Jews and Arabs Use (and Misuse) the History of Jerusalem to Score Points". Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Eli E. Hertz. "One Nation's Capital Throughout History" (PDF). Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8225-3218-7

- ISBN 0-385-04843-2

- ^ "'Massive' ancient wall uncovered in Jerusalem". CNN. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, 1992 pp. 268, 270.

- ^ 2 Samuel 24:23, which literally has "Araunah the King gave to the King [David]".

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Review, Reading David in Genesis, Gary A. Rendsburg.

- ^ Peake's commentary on the Bible.

- ^ Rainbow, Jesse. "From Creation to Babel: Studies in Genesis 1–11" (PDF). RBL. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Asaf Shtull-Trauring (6 May 2011). "The Keys to the Kingdom". Haaretz.

- ^ Amihai Mazar (2010). "Archaeology and the Biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy". In Reinhard G. Kratz and Hermann Spieckermann (ed.). One God, One Cult, One Nation (PDF). De Gruyter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2010.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein (2010). "A Great United Monarchy?". In Reinhard G. Kratz and Hermann Spieckermann (ed.). One God, One Cult, One Nation (PDF). De Gruyter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013.

- ^ ISBN 9780743223386.

- ISBN 978-0-224-03977-2p. 207

- ISBN 978-1-62837-345-5.

- ISBN 0-06-130102-7.

- ^ Jan Assmann: Martyrium, Gewalt, Unsterblichkeit. Die Ursprünge eines religiösen Syndroms. In: Jan-Heiner Tück (Hrsg.): Sterben für Gott – Töten für Gott? Religion, Martyrium und Gewalt. [Deutsch]. Herder Verlag, Freiburg i. Br. 2015, 122–147, hier: S. 136.

- ^ Morkholm 2008, p. 290.

- ^ "John Hyrcanus II". www.britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. 18 March 2024.

- OCLC 840438627.

- ISBN 3-11-018964-X

- ^ A History of the Jewish People, ed. by H. H. Ben-Sasson, 1976, p. 247.

- OCLC 52847163.

- OCLC 1170143447.

The historical description is consistent with the archeological finds. Collapses of massive stones from the walls of the Temple Mount were exposed lying over the Herodian street running along the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. The residential buildings of the Ophel and the Upper City were destroyed by great fire. The large urban drainage channel and the Pool of Siloam in the Lower City silted up and ceased to function, and in many places the city walls collapsed. [...] Following the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE, a new era began in the city's history. The Herodian city was destroyed and a military camp of the Tenth Roman Legion established on part of the ruins. In around 130 CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian founded a new city in place of Herodian Jerusalem next to the military camp. He honored the city with the status of a colony and named it Aelia Capitolina and possibly also forbidding Jews from entering its boundaries

- ISSN 0022-2097.

- S2CID 164199980.

- OCLC 1294393934.

- ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (22 February 2007). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1996). "Judaism to Mishnah: 135–220 AD". In Hershel Shanks (ed.). Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism: A Parallel History of their Origins and Early Development. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society. p. 196.

- ISBN 978-90-04-41707-6.

- ^ Jacobson, David. "The Enigma of the Name Īliyā (= Aelia) for Jerusalem in Early Islam". Revision 4. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-02-865931-2.

- S2CID 162644246.

The phenomenon was most prominent in Judea, and can be explained by the demographic changes that this region underwent after the second Jewish revolt of 132-135 C.E. The expulsion of Jews from the area of Jerusalem following the suppression of the revolt, in combination with the penetration of pagan populations into the same region, created the conditions for the diffusion of Christians into that area during the fifth and sixth centuries. [...] This regional population, originally pagan and during the Byzantine period gradually adopting Christianity, was one of the main reasons that the monks chose to settle there. They erected their monasteries near local villages that during this period reached their climax in size and wealth, thus providing fertile ground for the planting of new ideas.

- ^ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, page 334: "Jews were forbidden to live in the city and were allowed to visit it only once a year, on the Ninth of Ab, to mourn on the ruins of their holy Temple."

- ^ Virgilio Corbo, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- ^ Zissu, Boaz [in Hebrew]; Klein, Eitan (2011). "A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 61 (2): 196–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, p. 144, at Google Books, Oxford University Press 2014 p. 144.

- ISBN 9781107036567.

- ^ Conybeare, Frederick C. (1910). The Capture of Jerusalem by the Persians in 614 AD. English Historical Review 25. pp. 502–17.

- ^ Hidden Treasures in Jerusalem Archived 6 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, the Jerusalem Tourism Authority

- ^ Jerusalem blessed, Jerusalem cursed: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy City from David's time to our own. By Thomas A. Idinopulos, I.R. Dee, 1991, p. 152

- ^ Horowitz, Elliot. "Modern Historians and the Persian Conquest of Jerusalem in 614". Jewish Social Studies. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Rodney Aist, The Christian Topography of Early Islamic Jerusalem, Brepols Publishers, 2009 p. 56: 'Persian control of Jerusalem lasted from 614 to 629'.

- S2CID 159680405. Archived from the originalon 9 December 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Khalek, N. (2011). Jerusalem in Medieval Islamic Tradition. Religion Compass, 5(10), 624–630. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2011.00305.x. "One of the most pressing issues in both medieval and contemporary scholarship related to Jerusalem is weather the city is explicitly referenced in the text of the Qur'an. Sura 17, verse 1, which reads [...] has been variously interpreted as referring to the miraculous Night Journey and Ascension of Muhammad, events recorded in medieval sources and known as the isra and miraj. As we will see, this association is a rather late and even a contested one. [...] The earliest Muslim work on the Religious Merits of Jerusalem was the Fada'il Bayt al-Maqdis by al-Walid ibn Hammad al-Ramli (d. 912 CE), a text which is recoverable from later works. [...] He relates the significance of Jerusalem vis-a-vis the Jewish Temple, conflating 'a collage of biblical narratives' and comments pilgrimage to Jerusalem, a practice which was controversial in later Muslim periods."

- ^ "Miʿrād̲j̲". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 7 (New ed. 2006 ed.). Brill. 2006. pp. 97–105.

For this verse, tradition gives three interpretations: The oldest one, which disappears from the more recent commentaries, detects an allusion to Muhammad's Ascension to Heaven. This explanation interprets the expression al-masjid al-aksa, "the further place of worship" in the sense of "Heaven" and, in fact, in the older tradition isra is often used as synonymous with miradj (see Isl., vi, 14). The second explanation , the only one given in all the more modern commentaries, interprets masjid al-aksa as "Jerusalem" and this for no very apparent reason. It seems to have been an Umayyad device intended to further the glorification of Jerusalem as against that of the holy territory (cf. Goldziher, Muh. Stud., ii, 55-6; Isl, vi, 13 ff), then ruled by Abd Allah b. al-Zubayr. Al-Tabarl seems to reject it. He does not mention it in his History and seems rather to adopt the first explanation.

- ^ Silverman, Jonathan (6 May 2005). "The opposite of holiness". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 12 September 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ISBN 90-411-8843-6.

- ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- ^ "The travels of Nasir-i-Khusrau to Jerusalem, 1047 C.E." Homepages.luc.edu. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ Weksler-Bdolah, Shlomit (2011). Galor, Katharina; Avni, Gideon (eds.). Early Islamic and Medieval City Walls of Jerusalem in Light of New Discoveries. Eisenbrauns. p. 417. Retrieved 7 January 2018 – via Offprint posted at academia.edu.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bréhier, Louis Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291) Catholic Encyclopedia 1910, accessed 11 March 2008

- ^ Seder ha-Dorot, 1878, p. 252.

- ^ Epstein, in Monatsschrift, vol. xlvii, p. 344; Jerusalem: Under the Arabs.

- ^ ISBN 9780905035338.

- ^ ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-77155-2. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "cenacle - definition of cenacle by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Custodia Terræ Sanctæ". Custodia.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "The Palestinian – Israel Conflict » Felix Fabri". Zionismontheweb.org. 9 September 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Palestine Pilgrims Text Society, Vol. 9–10, pp. 384–91

- ^ "Holy Land Custody". Fmc-terrasanta.org. 30 November 1992. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Role of Franciscans

- ^ "The Custody". Custodia.org. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ISBN 9780395353752. p. 62.

- .

- ISBN 9780863568015.

- ISBN 9781438424750.

- ^ Tudor Parfitt (1997). The road to redemption: the Jews of the Yemen, 1900–1950. Brill's series in Jewish Studies, vol 17. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 53.

- ISBN 0-8050-6884-8.

- ^ Amos Elon, "Jerusalem: City of Mirrors". New York: Little, Brown 1989.

- S2CID 195011405.

- ^ Shamir, Ronen (2013) Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- ^ "Chart of the population of Jerusalem". Focusonjerusalem.com. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Tamari, Salim (1999). "Jerusalem 1948: The Phantom City". Jerusalem Quarterly File (3). Archived from the original (Reprint) on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ Eisenstadt, David (26 August 2002). "The British Mandate". Jerusalem: Life Throughout the Ages in a Holy City. Bar-Ilan University Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies. Archived from the original on 16 December 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ "History". The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, Revisited, Cambridge, 2004

- ^ Krystall, Nathan. "The De-Arabization of West Jerusalem 1947–50", Journal of Palestine Studies (27), Winter 1998

- ^ Al-Khalidi, Walid (ed.), All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, (Washington DC: 1992), "Lifta", pp. 300–03

- ^ Al-Khalidi, Walid (ed.), All that remains: the Palestinian villages occupied and depopulated by Israel in 1948, (Washington DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992)

- ISBN 0-521-86662-6

- ^ Jerusalem – 1948, 1967, 2000: Setting the Record Straight by Gerald M. Steinberg (Bar-Ilan University)

- ^ Anwar Abu Eisheh. Sacred Space in Israel and Palestine:Religion and Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 78.

- ^ Temple Mount destruction stirred archaeologist to action, 8 February 2005 | by Michael McCormack, Baptist Press "Temple Mount destruction stirred archaeologist to action - Baptist Press". Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Turner, Ashley (17 May 2018). "After US embassy makes controversial move to Jerusalem, more countries follow its lead". CNBC.

- ^ "Letter dated October 16, 1987, from the Permanent Representative of Jordan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General"[permanent dead link] UN General Assembly Security Council

- ^ "Elad in Silwan: Settlers, Archaeologists and Dispossession". mathaba.net. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- ^ Meron Rapoport.Land lords Archived 20 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine; Haaretz, 20 January 2005

- ^ Yigal Bronner. "Archaeologists for hire: A Jewish settler organisation is using archaeology to further its political agenda and oust Palestinians from their homes"; The Guardian, 1 May 2008

- ^ Ori Kashti and Meron Rapoport."Settler group refuses to vacate land slated for school for the disabled"; Haaretz, 15 January 2008

- ^ "The Other Israel: America-Israel Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace newsletter". Archived from the original on 8 July 2008.

- ^ Seth Freedman (26 February 2008). "Digging into trouble". The Guardian.

- ^ "Group 'Judaizing' East Jerusalem accused of withholding donation sources". Haaretz. 21 November 2007.

- ^ "11 Jewish families move into J'lem neighborhood of Silwan". Haaretz. 1 April 2004.

Sources

- ISBN 0-679-43596-4.

- Morkholm, Otto (2008). "Antiochus IV". In William David Davies; Louis Finkelstein (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 2, The Hellenistic Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–291. ISBN 978-0-521-21929-7.

Further reading

- Avci, Yasemin, Vincent Lemire, and Falestin Naili. "Publishing Jerusalem's ottoman municipal archives (1892-1917): a turning point for the city's historiography." Jerusalem Quarterly 60 (2014): 110+. online

- Emerson, Charles. 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War (2013) compares Jerusalem to 20 major world cities; pp 325–46.

- Lemire, Vincent. Jerusalem 1900: The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities (U of Chicago Press, 2017).

- Mazza, Roberto. Jerusalem from the Ottomans to the British ( 2009)

- Millis, Joseph. Jerusalem: The Illustrated History of the Holy City (2012) excerpt

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag. Jerusalem: The Biography (2012) excerpt

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Jerusalem (71–1099) – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Jerusalem, Latin Kingdom of (1099–1291) – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Jerusalem (After 1291) – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- 4,000-year-old cemetery uncovered in Jerusalem (8 November 2006)

- Jerusalem Through Coins