History of Laos

| History of Laos | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Muang city-states era | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Lan Xang era | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Regional kingdoms era | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Colonial era | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Independent era | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| See also | ||||||||

Evidence of modern human presence in the northern and central highlands of

Laos exists in truncated form from the thirteenth-century Lao kingdom of

Limitations and current state of research

Archaeological exploration in Laos has been limited due to rugged and remote topography, a history of twentieth century conflicts which have left over two million tons of

Prehistory

An early tradition is discernible in the Hoabinhian, the name given to an industry and cultural continuity of stone tools and flaked cobble artifacts that appears around 10,000 BP in caves and rock shelters first described in Hòa Bình, Vietnam and later also in Laos.[10][11]

Neolithic migrations

The earliest inhabitants of Laos—

Subsequent Neolithic immigration waves are considered dynamic, very complex and are intensely debated. Researchers resort to linguistic terms and argumentation for group identification and classification.[12]

Agriculture and bronze production

Wet-rice and millet farming techniques were introduced from the Yangtze River valley in southern China since around 2,000 years BC. Hunting and gathering remained an important aspect of food provision; particularly in forested and mountainous inland areas.

Plain of Jars

From the 8th century BCE to as late as the 2nd century CE, an inland trading society emerged on the

Early Indianised kingdoms

Funan kingdom

The first indigenous kingdom to emerge in

Champa kingdom

By the 2nd century CE, Austronesian settlers had established an Indianised kingdom known as

Chenla kingdom

The capital of early

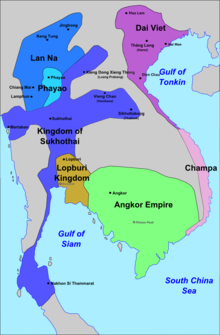

By the 8th century CE, Chenla had divided into "Land Chenla" located in Laos, and "Water Chenla" founded by Mahendravarman near Sambor Prei Kuk in Cambodia. Land Chenla was known to the Chinese as "Po Lou" or "Wen Dan" and dispatched a trade mission to the Tang dynasty court in 717 CE. Water Chenla, would come under repeated attack from Champa, the Mataram sea kingdoms in Indonesia based in Java, and finally pirates. From the instability the Khmer emerged.[21]

Dvaravati city-state kingdoms

In the area that is modern northern and central Laos and northeast Thailand, the

Tai migrations

There have been many theories proposing the origin of the

.James R. Chamberlain (2016) proposes that Tai-Kadai (Kra-Dai) language family was formed as early as the 12th century BCE in the middle Yangtze basin, coinciding roughly with the establishment of the

The Tai, from their new home in Southeast Asia, were influenced by the Khmer and the Mon and most importantly Buddhist India. The Tai

The Legend of Khun Borom

The history of the Tai migrations into Laos were preserved in myth and legends. The Nithan Khun Borom or "Story of

Lan Xang (1353–1707)

Lan Xang (1353–1707) was one of the largest kingdoms in Southeast Asia. Also known as the "Land of a million elephants under the white parasol" the kingdom's name alludes to the power of the kingship and formidable war machine of the early kingdom. The founding of Lan Xang was recorded in 1353, after a series of conquests by

Lan Xang existed as a sovereign kingdom for over 350 years. The first serious foreign invasion came from the

The Burmese Toungoo dynasty began a series of expansions during the late 1550s which culminated under King Bayinnaung. Setthathirath moved the capital of Lan Xang from Luang Prabang to Vientiane in 1560, to better defend against the threat of Burma and to more ably administer the central and southern provinces. Bayinnaung subjugated the Kingdom of Lanna and went on to destroy the kingdom and city of Ayutthaya in 1564. King Setthathirath fought two successful guerilla campaigns against the Burmese invasions, leaving Lan Xang the only independent Tai kingdom until his death in 1572, while on campaign against the Khmer. The Burmese succeeded with the third invasion of Lan Xang around 1573, and Lan Xang became a vassal state until 1591 when the son of Setthathirath, Nokeo Koumane, was able to successfully reassert independence.

Lan Xang recovered and reached the apex of its political and economic power during the seventeenth century under King Sourigna Vongsa, who became the longest reigning of Lan Xang's monarchs (1637–1694) after defeating four rival claimants to the throne. Foreign relations was managed successfully during his reign and the king was known as a firm and just ruler. In the 1640s the first European explorers to leave a detailed account of the kingdom arrived looking to establish trade and secure Christian converts, both were ultimately largely unsuccessful. However, these European visitors reported on the capital's (Vientiane) prosperity and imposing religious buildings. King Sourigna Vongsa was known to uphold the law stricty, an episode exemplified this when he did not intervene when his son (and successor) was sentenced to death when it was found that he seduced the wife of a senior court official. Upon the death of Sourigna Vongsa a succession dispute as well as exploitation by both Ayutthaya and Dai Viet, led to the kingdom of Lan Xang being ultimately divided into constituent kingdoms in 1707.[15][16][34]

Regional kingdoms (1707–1779)

Beginning in 1707 the Lao kingdom of

The Kingdom of Luang Prabang was the first of the regional kingdoms to emerge in 1707, when King Xai Ong Hue of Lan Xang was challenged by Kingkitsarat, the grandson of

In 1713, the southern Lao nobility continued the rebellion against Xai Ong Hue under

rivers on the Khorat Plateau. Although less populous than either Luang Prabang or Vientiane, Champasak occupied an important position for regional power and international trade via the Mekong River.Throughout the 1760s and 1770s the kingdoms of Siam and

Siam and suzerainty (1779–1893)

By 1779, General

However, by 1782 Taksin had been deposed and

Siribunnyasan the last independent king of Vientiane had died by 1780, and his sons Nanthasen, Inthavong, and

Anouvong's and Lao nationalism

Anouvong is a symbolic and controversial figure even today, his short lived rebellion against Siam from 1826 to 1829 ultimately proved futile and led to the total annihilation of

The history of forced population transfers, corvee labor projects, loss of national symbols and prestige (most notably the Emerald Buddha) formed the backdrop to specific actions taken by

In 1819, a rebellion in Champasak provided Anouvong with opportunity, and he dispatched an army under his son Nyo who managed to suppress the conflict. In exchange Anouvong successfully made the case that his son be crowned as king in Champasak, which was confirmed by Bangkok. Anouvong had successfully expanded his influence throughout Vientiane, Isan, Xieng Khouang and now Champasak. Anouvong dispatched a number of diplomatic missions to Luang Prabang, which were viewed suspiciously in light of his growing regional influence.

By 1825 Rama II had died, and Rama III was consolidating his position against prince Mongkut (Rama IV). In the ensuing power struggle before the accession of Rama III one of Anouvong's grandsons was killed. When Anouvong arrived for the funerary services, he made several requests of the king Rama III which were dismissed including the return of his sister who had been captured in 1779, and Lao families which had been relocated to Saraburi near Bangkok. Before returning to Vientiane, Anouvong's son Ngau, the crown prince, was forced to perform manual labor during which he was beaten.

Early in his reign, Rama III ordered a census of all peoples on the Khorat Plateau, the census involved the forced tattooing of each villager's census number and name of their village. The aim of the policy was to more tightly administer Lao territories from Bangkok and was facilitated by the nobility Siam had installed in the newly created cities throughout the region. Popular resentment against the forced tattooing and increased taxes became casus belli for rebellion.

Toward the end of 1826 Anouvong was making military preparations for armed rebellion. Anouvong's strategy involved three objectives, first was to repatriate all ethnic Lao living in Siam to the right bank of the Mekong and execute any Siamese engaged in the tattooing of Lao, the second objective was to consolidate Lao power by forging an alliance with Chiang Mai and Luang Prabang, the third and final goal was to gain international support from either the Vietnamese, Chinese, Burmese or British. In January hostilities commenced, and the Lao armies were sent from Vientiane to capture Nakhon Ratchasima,

Anouvong's forces pushed south eventually to

Aftermath and Vietnamese intervention

Following the Anouvong's rebellion Siam and Vietnam were increasingly at odds over control of the

In the aftermath of Vientiane's destruction the Siamese divided the

Population transfers and slavery

Population transfers of ethnic Lao to Siam began in 1779 with Siamese suzerainty. Artisans and members of the court were forcibly moved to Saraburi near Bangkok, and several thousand farmers and peasant who were transported throughout

Although slavery existed in Lao areas before the rebellion in 1828, the defeat and subsequent removal of most ethnic Lao left a depopulated and vulnerable position for the remaining people of the East Bank of the Mekong. Lao Theung hill tribes which had little involvement in the 1828 rebellion bore the brunt of organized slave raids into Laos and became known collectively and pejoratively in Thai and Lao as kha or "slaves." Lao Theung were hunted or sold into slavery frequent organized raiding parties from Vietnam, Cambodia, Siam, Laos and China. Larger tribes of Lao Theung, such as the Brao, would conduct slave raids against weaker tribes. The raids continued throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, a Siamese military campaign in Laos in 1876 was described by a British observer as having been "transformed into slave-hunting raids on a large scale".

The population transfers and slave raids ameliorated toward the end of the nineteenth century when European observers and anti-slavery groups made their presence increasingly difficult for the Bangkok elite. In 1880, both slave raiding and trading became illegal, although debt slavery would persist until 1905 by decree of King

Haw Wars

In the 1840s, sporadic rebellions, slave raids, and movement of refugees throughout the areas that would become modern Laos left whole regions politically and militarily weak. In China the Qing dynasty was pushing south to incorporate hill peoples into the central administration, at first floods of refugees and later bands of rebels from the Taiping Rebellion pushed into Lao lands. The rebel groups became known by their banners and included the Yellow (or Striped) Flags, Red Flags and the Black Flags. The bandit groups rampaged throughout the countryside, with little response from Siam.

During the early and mid-nineteenth century the first

By the 1860s, the first French explorers were pushing north charting the path of the Mekong River, with hope of a navigable waterway to southern China. Among the early French explorers was an expedition led by Francis Garnier, who was killed during an expedition by Haw rebels in Tonkin. The French would increasingly conduct military campaigns against the Haw in both Laos and Vietnam (Tonkin) until the 1880s.[15][16]

Colonial period

Origins of French colonialism in Laos

French colonial interests in Laos began with the exploratory missions of

Pavie and French auxiliaries arrived in Luang Prabang in 1887 in time to witness an attack on Luang Prabang by Chinese and Tai bandits who hoped to liberate the brothers of their leader

The French were aware that the east-bank territories of the Mekong were "a depopulated, devastated country"—the Siamese forced population transfers following the

1893–1939

The

As part of

Under French rule, the Vietnamese were encouraged to migrate to Laos, which was seen by the French colonists as a rational solution to a practical problem within the confines of an Indochina-wide colonial space.[35] By 1943, the Vietnamese population stood at nearly 40,000, forming the majority in the largest cities of Laos and enjoying the right to elect their own leaders.[36] As a result, 53% of the population of Vientiane, 85% of

The Lao response to French colonialism was mixed, although the French were viewed as preferable to the Siamese by the nobility, the majority of

In 1914, the

By 1920, the majority of

World War II

Developing Lao national identity gained importance in 1938 with the rise of the ultranationalist prime minister

Yet the wider impact of World War II had little effect on Laos until February 1945, when a detachment from the

Lao Issara and independence

1945 was a watershed year in the history of Laos. Under Japanese pressure, King

Kingdom of Laos and the Lao Civil War (1953–1975)

Elections were held in 1955, and the first coalition government, led by Prince

A second Geneva conference, held in 1961–62, provided for the independence and

Shortly after the

Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–present)

The new communist government led by Kaysone Phomvihane imposed centralized economic decision-making and incarcerated many members of the previous government and military in "re-education camps" which also included the Hmong. While nominally independent, the communist government was for many years effectively little more than a puppet regime run from Vietnam.

The government's policies prompted about 10 percent of the Lao population to leave the country. Laos depended heavily on Soviet aid channeled through Vietnam up until the Soviet collapse in 1991. In the 1990s the communist party gave up centralised management of the economy but still has a monopoly of political power.[16][39]

Explanatory notes

References

Citations

- ISBN 9781119251545.

- ^ a b Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014). Layers of Chinese loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, Special Issue No 20: 47–64.

- ^ "Origins of Ethnolinguistic Identity in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Roger Blench. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Laos Brief History". Asia Web Direct. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Laos History". The National Assembly of Laos. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Lao People's Democratic Republic History Timeline". Worldatlas Com. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Oldest bones from modern humans in Asia discovered". CBSNews. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Marwick, Ben; Bouasisengpaseuth, Bounheung (2017). "History and Practice of Archaeology in Laos". In Habu, Junko; Lape, Peter; Olsen, John (eds.). Handbook of East and Southeast Asian Archaeology. Springer.

- PMID 25849125.

- .

- . Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-66369-4. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Charles Higham. "Hunter-Gatherers in Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to the Present". Digitalcommons. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- S2CID 162300712. Retrieved 11 February 2017 – via Researchgate.net.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Maha Sila Viravond. "History of laos" (PDF). Refugee Educators' Network. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p M.L. Manich. "History of Laos (including the history of Lonnathai, Chiangmai)" (PDF). Refugee Educators' Network. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- OCLC 57054139.

- . Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8248-0843-3.

- ^ National Library of Australia. Asia's French Connection : George Coedes and the Coedes Collection Archived 21 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations by Charles F. W. Higham – Chenla – Chinese histories record that a state called Chenla..." (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam", p. 67. In Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 104, 2016.

- ^ Baker, Chris and Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). "A History of Ayutthaya", p. 27. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Du Yuting; Chen Lufan (1989). "Did Kublai Khan's Conquest of the Dali Kingdom Give Rise to the Mass Migration of the Thai People to the South?" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 77.1c (digital). Siam Heritage Trust. image 7 of p. 39. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

The Thai people in the north as well as in the south did not in any sense "migrate en masse to the south" after Kublai Khan's conquest of the Dali Kingdom.

- ^ a b c Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam", pp. 27–77. In Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 104, 2016.

- ^ Grant Evans. "A Short History of Laos – The land in between" (PDF). Higher Intellect – Content Delivery Network. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ a b Baker 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b Taylor 1991, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d Baker & Phongpaichit 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 239–249.

- ^ "Complete mitochondrial genomes of Thai and Lao populations indicate an ancient origin of Austroasiatic groups and demic diffusion in the spread of Tai–Kadai languages" (PDF). Max Planck Society. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "A Short History of South East Asia Chapter 3. The Repercussions of the Mongol Conquest of China ...The result was a mass movement of Thai peoples southwards..." (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- S2CID 165680758.

- ^ Church, Peter (2017). A Short History of South-East Asia (6 ed.). Singapore: Wiley. p. 77.

- ISBN 978-8-776-94023-2.

- ^ a b c d

Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge University Press, p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-59746-3.

- ^ Wiseman, Paul (11 December 2003). "30-year-old bombs still very deadly in Laos". Usatoday.Com. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- ^ Martin Stuart-Fox. "Politics and Reform in the Lao People's Democratic Republic)" (PDF). University of Queensland. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

Works cited

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017), A History of Ayutthaya, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4

- Baker, Chris (2002), "From Yue To Tai" (PDF), Journal of the Siam Society, 90 (1–2): 1–26

- Taylor, Keith W. (1991), The Birth of Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0

Further reading

- Conboy, K. The War in Laos 1960–75 (Osprey, 1989)

- Dommen, A. J. Conflict in Laos (Praeger, 1964)

- Gunn, G. Rebellion in Laos: Peasant and Politics in a Colonial Backwater (Westview, 1990)

- Kremmer, C. Bamboo Palace: Discovering the Lost Dynasty of Laos (HarperCollins, 2003)

- Pholsena, Vatthana. Post-war Laos: The politics of culture, history and identity (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006).

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. "The French in Laos, 1887–1945." Modern Asian Studies (1995) 29#1 pp: 111–139.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. A history of Laos (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- Stuart-Fox, M. (ed.). Contemporary Laos (U of Queensland Press, 1982)

External links

- Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts – an online library of historical Lao manuscripts and related background information

- Laos Travel Guide History of Laos

- Andrea Matles Savada, ed. (1994). "Laos: A Country Study". GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 8 August 2011.