History of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

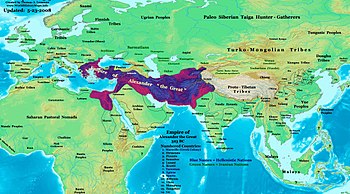

The

During the age of

Philip II came to power when his older brother

Macedonia continued its role as the dominant state of

Early history and legend

The

Very little is known about the

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers

After

Involvement in the Classical Greek world

Alexander I, who Herodotus claimed was entitled

War broke out in 433 BC when Athens, perhaps seeking additional cavalry and resources in anticipation of the

In 429 BC, Perdiccas II sent aid to the Spartan commander Cnemus in Acarnania, but the Macedonian forces arrived too late to enter the Battle of Naupactus, which ended in an Athenian victory.[41] In that same year, Sitalces, according to Thucydides, invaded Macedonia at the behest of Athens to aid them in subduing Chalcidice and to punish Perdiccas II for violating the terms of their peace treaty.[42] However, given Sitalces' huge Thracian invading force (allegedly 150,000 soldiers) and a nephew of Perdiccas II that he intended to place on the Macedonian throne after toppling the latter's regime, Athens must have become wary of acting on their supposed alliance since they failed to provide him with promised naval support.[43] Sitalces eventually retreated from Macedonia, perhaps due to logistical concerns: a shortage of provisions and harsh winter conditions.[44]

In 424 BC, Perdiccas began to play a prominent role in the Peloponnesian War by aiding the Spartan general

Perdiccas II was obliged to send aid to the Athenian general

Archelaus I maintained good relations with Athens throughout his reign, relying on Athens to provide naval support in his 410 BC siege of Pydna, and in exchange providing Athens with timber and naval equipment.[54] With improvements to military organization and building of new infrastructure such as fortresses, Archelaus was able to strengthen Macedonia and project his power into Thessaly, where he aided his allies; yet he faced some internal revolt as well as problems fending off Illyrian incursions led by Sirras.[55] Although he retained Aigai as a ceremonial and religious center, Archelaus I moved the capital of the kingdom north to Pella, which was then positioned by a lake with a river connecting it to the Aegean Sea.[56] He improved Macedonia's currency by minting coins with a higher silver content as well as issuing separate copper coinage.[57] His royal court attracted the presence of well-known intellectuals such as the Athenian playwright Euripides.[58]

Historical sources offer wildly different and confused accounts as to who assassinated Archelaus I, although it likely involved a

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus provided a seemingly conflicting account about Illyrian invasions occurring in 393 BC and 383 BC, which may have been representative of a single invasion led by

Amyntas III had children with two wives, but it was his eldest son by his marriage with

Rise of Macedon

Right: another bust of Philip II, a 1st-century AD Roman copy of a Hellenistic Greek original, now in the Vatican Museums

Philip II of Macedon (r. 359 – 336 BC), who spent much of his adolescence as a political hostage in Thebes, was twenty-four years old when he acceded to the throne and immediately faced crises that threatened to topple his leadership.[72] However, with the use of deft diplomacy, he was able to convince the Thracians under Berisades to cease their support of Pausanias, a pretender to the throne, and the Athenians to halt their backing of another pretender named Arg(a)eus (perhaps the same who had caused trouble for Amyntas III).[73] He achieved these by bribing the Thracians and their Paeonian allies and removing a garrison of Macedonian troops from Amphipolis, establishing a treaty with Athens that relinquished his claims to that city.[74] He was also able to make peace with the Illyrians who had threatened his borders.[75]

The exact date in which Philip II initiated reforms to radically transform the Macedonian army's organization, equipment, and training is unknown, including the formation of the Macedonian phalanx armed with long pikes (i.e. the sarissa). The reforms took place over a period of several years and proved immediately successful against his Illyrian and Paeonian enemies.[76] Confusing accounts in ancient sources have led modern scholars to debate how much Philip II's royal predecessors may have contributed to these military reforms. It is perhaps more likely that his years of captivity in Thebes during the Theban hegemony influenced his ideas, especially after meeting with the renowned general Epaminondas.[77]

Although Macedonia and the rest of Greece traditionally practiced

While Athens was preoccupied with the Social War (357–355 BC), Philip took this opportunity to retake Amphipolis in 357 BC, for which the Athenians later declared war on him, and by 356 BC, recaptured Pydna and Potidaea, the latter of which he handed over to the Chalcidian League as promised in a treaty of 357/356 BC.[84] In this year, he was also able to take Crenides, later refounded as Philippi and providing much wealth in gold, while his general Parmenion was victorious against the Illyrian king Grabos II of the Grabaei.[85] During the siege of Methone from 355 to 354 BC, Philip lost his right eye to an arrow wound, but was able to capture the city and was even cordial to the defeated inhabitants (unlike the Potidaeans, who had been sold into slavery).[86]

It was at this stage when Philip II involved Macedonia in the

After campaigning against the Thracian ruler

For the next few years Philip II was occupied with reorganizing the administrative system of Thessaly, campaigning against the Illyrian ruler

After the Macedonian victory at Chaeronea, Philip II imposed harsh conditions on Thebes, installing an

After his election by the League of Corinth as their

Empire

Right: Bust of Alexander the Great, a Roman copy of the Imperial Era (1st or 2nd century AD) after an original bronze sculpture made by the Greek sculptor Lysippos, Louvre, Paris

Before Philip II was assassinated in the summer of 336 BC, relations with his son Alexander had degenerated to the point where he excluded him entirely from his planned invasion of Asia, choosing instead for him to act as

In 335 BC, Alexander led a campaign against the Thracian tribe of the

Throughout his military career and kingship, Alexander won every battle that he personally commanded.

Despite his skills as a commander, Alexander perhaps undercut his own rule by demonstrating signs of

Meanwhile, in Greece the only disturbance to Macedonian rule was the attempt by the

When Alexander the Great died at Babylon in 323 BC, his mother Olympias immediately accused Antipater and his faction with poisoning him, although there is no evidence to confirm this.[138] With no official heir apparent, the loyalties of the Macedonian military command became split between one side proclaiming Alexander's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus (r. 323 – 317 BC) as king and another siding with Alexander's infant son with Roxana, Alexander IV (r. 323 – 309 BC).[139] Except for the Euboeans and Boeotians, the Greeks also immediately rose up in a rebellion against Antipater known as the Lamian War (323–322 BC).[140] When Antipater was defeated at the 323 BC Battle of Thermopylae, he fled to Lamia where he was besieged by the Athenian commander Leosthenes. Leonnatus rescued Antipater by lifting the siege.[141] Although Antipater ultimately subdued the rebellion, he died in 319 BC and left a vacuum of power wherein the two proclaimed kings of Macedonia became pawns in a power struggle between the diadochi, the former generals of Alexander's army who were now carving up his empire.[142]

A

Forming an alliance with Ptolemy, Antigonus, and Lysimachus, Cassander had his officer Nicanor capture the Munichia fortress of Athens' port town Piraeus in defiance of Polyperchon's decree that Greek cities should be free of Macedonian garrisons, sparking the Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC).[148] Given a string of military failures by Polyperchon, in 317 BC Philip III, by way of his politically-engaged wife Eurydice II of Macedon, officially replaced him as regent with Cassander.[149] Afterwards Polyperchon desperately sought the aid of Olympias, mother of Alexander III who still resided in Epirus.[149] A joint force of Epirotes, Aetolians, and Polyperchon's troops invaded Macedonia and forced the surrender of Philip III and Eurydice's army, allowing Olympias to execute the king and force his queen to commit suicide.[150] Olympias then had Nicanor killed along with dozens of leading Macedonian nobles, yet by the spring of 316 BC Cassander defeated her forces, captured her, and placed her on trial for murder before sentencing her to death.[151]

Cassander married Philip II's daughter

Hellenistic era

The beginning of

Cassander died in 297 BC and his sickly son

War broke out between Pyrrhus and Demetrius in 290 BC when

By 286 BC, Lysimachus was able to expel Pyrrhus and his forces from Macedonia altogether, yet in 282 BC, a new war erupted between Lysimachus and Seleucus I.

Beginning in 280 BC, Pyrrhus embarked on a campaign in

Pyrrhus lost much of his support among the Macedonians in 273 BC when his unruly Gallic mercenaries plundered the royal cemetery of

The Antigonid naval fleets docked at

However, in 251 BC,

Demetrius II's control of Greece diminished by the end of his reign, though, when he lost

Although the Achaean League had been fighting Macedonia for decades, Aratus sent an embassy to Antigonus III in 226 BC seeking an unexpected alliance now that the reformist king Cleomenes III of Sparta was threatening the rest of Greece in the Cleomenean War (229–222 BC).[190] In exchange for military aid, Antigonus III demanded the return of Corinth to Macedonian control, which Aratus finally agreed to in 225 BC.[191] Antigonus III's first move against Sparta was to capture Arcadia in the spring of 224 BC.[192] After reforming a Hellenic league in the same vein as Philip II's League of Corinth and hiring Illyrian mercenaries for additional support, Antigonus III managed to defeat Sparta at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC.[193] For the first time in Sparta's history, their city was then occupied by a foreign power, restoring Macedonia's position as the leading power in Greece.[194] Antigonus died a year later, perhaps from tuberculosis, leaving behind a strong Hellenistic kingdom for his successor Philip V.[195]

Conflict with Rome

In 215 BC, at the height of the

A year after the Aetolian League concluded a

While Philip V was ensnared in a conflict with several Greek maritime powers, Rome viewed these unfolding events as an opportunity to punish a former ally of Hannibal, come to the aid of its Greek allies, and commit to a war that perhaps required a limited amount of resources in order to achieve victory.

Although the Macedonians were able to successfully defend their territory for roughly two years,[217] the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus managed to expel Philip V from Macedonia in 198 BC with him and his forces taking refuge in Thessaly.[218] When the Achaean League abandoned Philip V to join the Roman-led coalition, the Macedonian king sued for peace, but the terms offered were considered too stringent and so the war continued.[218] In June 197 BC, the Macedonians were defeated at the Battle of Cynoscephalae.[219] Rome, dismissing the Aetolian League's demands to dismantle the Macedonian monarchy altogether, ratified a treaty that forced Macedonia to relinquish control of much of its Greek possessions, including Corinth, while allowing it to preserve its core territory, if only to act as a buffer against Illyrian and Thracian incursions into Greece.[220] Although the Greeks, especially the Aetolians, suspected Roman intentions of supplanting Macedonia as the new hegemonic power in Greece, Flaminius announced at the Isthmian Games of 196 BC that Rome intended to preserve Greek liberty by leaving behind no garrisons or exacting tribute of any kind.[221] This promise was delayed due to the Spartan king Nabis capturing Argos, necessitating Roman intervention and a peace settlement with the Spartans, yet the Romans finally evacuated Greece in the spring of 194 BC.[222]

Encouraged by the Aetolian League and their calls to liberate Greece from the Romans, the

While becoming increasingly entangled in Greek affairs and failing to please all sides in various disputes, the Roman Senate decided in 184/183 BC to force Philip V to abandon the cities of

Eumenes II came to Rome in 172 BC and delivered a speech to the Senate denouncing the alleged crimes and transgressions of Perseus.[232] This convinced the Roman Senate to declare the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC), although Klaus Bringmann asserts that negotiations with Macedonia were completely ignored due to Rome's "political calculation" that the Macedonian kingdom had to be destroyed in order to ensure the elimination of the "supposed source of all the difficulties which Rome was having in the Greek world".[233] Although Perseus' forces were victorious against the Romans at the Battle of Callinicus in 171 BC, the Macedonian army was defeated at the Battle of Pydna in June 168 BC.[234] Perseus fled to Samothrace but surrendered shortly afterwards, was brought to Rome for the triumph of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, and placed under house arrest at Alba Fucens where he died in 166 BC.[235]

The Romans formally disestablished the Macedonian monarchy by installing four separate allied

See also

- Ancient Macedonians

- Ancient Macedonian language

- Antigonid Macedonian army

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Government of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

- List of ancient Macedonians

- Macedonians (Greeks)

- Macednon

References

- ISBN 978-1597975193.

That sense of being one people allowed each Greek state and its citizens to contribute their values, experiences, traditions, resources, and talents to a new national identity and psyche. It was not until Philip's reign that a common sentiment of what it meant to be a Hellene reached all Greeks. Alexander took this culture of Hellenism with him to Asia, but it was Philip, as leader of the Greeks, who created it and in doing so made the Hellenistic Age possible.

- ISBN 978-1444334128.

He [Philip] also recognized the power of pan-hellenic sentiment when arranging Greek affairs after his victory at Chaironeia: a pan-hellenic expedition against Persia ostensibly was one of the main goals of the League of Corinth.

- ISBN 978-1551114323.

In the end, the Greeks would fall under the rule of a single man, who would unify Greece: Philip II, king of Macedon (360-336 BC). His son, Alexander the Great, would lead the Greeks on a conquest of the ancient Near East vastly expanding the Greek world.

- ^ a b King 2010, p. 376; Sprawski 2010, p. 127; Errington 1990, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Titus Livius, "The History of Rome", 45.9: "This was the end of the war between the Romans and Perseus, after four years of steady campaigning, and also the end of a kingdom famed over a large part of Europe and all of Asia. They reckoned Perseus as the twentieth after Caranus, who founded the kingdom."

- ^ Marcus Velleius Paterculus, "History of Rome", 1.6: "In this period, sixty-five years before the founding of Rome, Carthage was established by the Tyrian Elissa, by some authors called Dido. About this time also Caranus, a man of royal race, eleventh in descent from Hercules, set out from Argos and seized the kingship of Macedonia. From him Alexander the Great was descended in the seventeenth generation, and could boast that, on his mother's side, he was descended from Achilles, and, on his father's side, from Hercules.”

- ^ Justin, "Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus", 7.1.7: "But Caranus accompanied by a great multitude of Greeks, having been directed by an oracle to seek a settlement in Macedonia, and having come into Emathia, and followed a flock of goats that were fleeing from a tempest, possessed himself of the city of Edessa...”

- ^ Plutarch, “Alexander”, 2.1: "As for the lineage of Alexander, on his father's side he was a descendant of Heracles through Caranus, and on his mother's side a descendant of Aeacus through Neoptolemus; this is accepted without any question."

- ^ Pausanias, "Description of Greece", 9.40.8–9: "The Macedonians say that Caranus, king of Macedonia, overcame in battle Cisseus, a chieftain in a bordering country. For his victory Caranus set up a trophy after the Argive fashion, but it is said to have been upset by a lion from Olympus, which then vanished. Caranus, they assert, realized that it was a mistaken policy to incur the undying hatred of the non-Greeks dwelling around, and so, they say, the rule was adopted that no king of Macedonia, neither Caranus himself nor any of his successors, should set up trophies, if they were ever to gain the good-will of their neighbors. This story is confirmed by the fact that Alexander set up no trophies, neither for his victory over Dareius nor for those he won in India."

- ^ Errington 1990, p. 3.

- ^ King 2010, p. 376; Sprawski 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Badian 1982, p. 34; Sprawski 2010, p. 142.

- ^ King 2010, p. 376; Errington 1990, p. 251.

- ^ King 2010, p. 376.

- ^ Errington 1990, p. 2.

- ^ Lewis & Boardman 1994, pp. 723–724, see also Hatzopoulos 1996, pp. 105–108 for the Macedonian expulsion of original inhabitants such as the Phrygians.

- ^ Anson 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Anson 2010, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Thomas 2010, pp. 67–68, 74–78.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 343; Sprawski 2010, p. 134; Errington 1990, p. 8.

- Anthemousin 506 BC.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 343.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 343; Sprawski 2010, p. 136; Errington 1990, p. 10.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 344; Sprawski 2010, pp. 135–137; Errington 1990, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Sprawski 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 344; Errington 1990, p. 10.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, pp. 344–345; Sprawski 2010, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Sprawski 2010, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 345; Sprawski 2010, pp. 139–141; see also Errington 1990, pp. 11–12 for further details.

- ^ Sprawski 2010, pp. 141–142; Errington 1990, pp. 9, 11–12.

- ^ Sprawski 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 146; see also Errington 1990, pp. 13–14 for further details.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 146–147; Müller 2010, p. 171; Cawkwell 1978, p. 72; see also Errington 1990, pp. 13–14, 16 for further details.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 147; see also Errington 1990, p. 18 for further details.

- ^ a b Roisman 2010, p. 147.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 148.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 148; Errington 1990, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 149.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 149; Errington 1990, p. 20.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 149–150; Errington 1990, p. 20.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 150; Errington 1990, p. 20.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 150–151; Errington 1990, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 151–152; Errington 1990, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 152; Errington 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 152; Errington 1990, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 153; Errington 1990, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 153–154; see also Errington 1990, p. 23 for further details.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 154; see also Errington 1990, p. 23 for further details.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 154; Errington 1990, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 154–155; Errington 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 156; Errington 1990, p. 26.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 156–157; Errington 1990, p. 26.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 157–158; Errington 1990, p. 28.

- ^ a b Roisman 2010, p. 158; Errington 1990, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 158–159; see also Errington 1990, p. 30 for further details.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 159; see also Errington 1990, p. 30 for further details.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 159–160;

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 160; Errington 1990, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 161; Errington 1990, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 161–162; Errington 1990, p. 35.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 161–162; Errington 1990, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Roisman 2010, p. 162; Errington 1990, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Roisman 2010, pp. 162–163; Errington 1990, p. 36.

- ^ Roisman 2010, pp. 163–164; Errington 1990, p. 37.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 166–167; Buckley 1996, pp. 467–472.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 167–168; Buckley 1996, pp. 467–472.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 167–168; Buckley 1996, pp. 467–472; Errington 1990, pp. 38.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 167.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 168–169.

- Asia Minor (modern Turkey) soon after this wedding. Müller also suspects that this marriage was one of political convenience meant to ensure the loyalty of an influential Macedonian noble house.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 170; Buckler 1989, p. 62.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 170–171; Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 167, 169; Roisman 2010, p. 161.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 169, 173–174; Cawkwell 1978, p. 84; Errington 1990, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 171; Buckley 1996, pp. 470–472; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 172; Hornblower 2002, p. 272; Cawkwell 1978, p. 42; Buckley 1996, pp. 470–472.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 171–172; Buckler 1989, pp. 63, 176–181; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 185–187;

Cawkwell contrarily provides the date of this siege as 354–353 BC. - ^ Müller 2010, pp. 171–172; Buckler 1989, pp. 8, 20–22, 26–29.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 172–173; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 60, 185; Hornblower 2002, p. 272; Buckler 1989, pp. 63–64, 176–181;

Conversely, Buckler provides the date of this initial campaign as 354 BC, while affirming that the second Thessalian campaign ending in the Battle of Crocus Field occurred in 353 BC. - ^ Müller 2010, p. 173; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 62, 66–68; Buckler 1989, pp. 74–75, 78–80; Worthington 2008, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 173; Cawkwell 1978, p. 44; Schwahn 1931, col. 1193–1194.

- ^ Cawkwell 1978, p. 86.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 173–174; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 85–86; Buckley 1996, pp. 474–475.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 173–174; Worthington 2008, pp. 75–78; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 174; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 98–101.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 174–175; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 95, 104, 107–108; Hornblower 2002, pp. 275–277; Buckley 1996, pp. 478–479.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 175.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 175–176; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 114–117; Hornblower 2002, p. 277; Buckley 1996, p. 482; Errington 1990, p. 44.

- ^ Mollov & Georgiev 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 176; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 136–142; Errington 1990, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 176–177; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 143–148.

- ISBN 0-292-79142-9.

- ^ Müller 2010, p. 177; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 177–178; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 167–171; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 16 for further details.

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, pp. 348, 351

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, pp. 347–349

- ^ Olbrycht 2010, p. 351

- ^ Errington 1990, p. 227.

- ^ a b Müller 2010, pp. 179–180; Cawkwell 1978, p. 170.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 180–181; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 14 for further details.

- ^ Müller 2010, pp. 181–182; Errington 1990, p. 44; Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 186; see Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 3–5 for details of the arrests and judicial trials of other suspects in the conspiracy to assassinate Philip II of Macedon.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 189–190; Müller 2010, p. 183.

- F.W. Walbank discuss possible Macedonian as well as foreign suspects, such as Demosthenes and Darius III: Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 190; Müller 2010, p. 183; Renault 2001, pp. 61–62; Fox 1980, p. 72; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 3–5 for further details.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 186.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 190.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 190–191; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 15–16 for further details.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191; Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 34–38.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191; Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 40–47.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191; see also Errington 1990, p. 91 and Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 47 for further details.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 191–192; see also Errington 1990, pp. 91–92 for further details.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b c Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 193.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 193–194; Holt 2012, pp. 27–41.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 194; Errington 1990, p. 113.

- ^ a b Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 195.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Errington 1990, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Holt 1989, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 196.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 199; Errington 1990, p. 93.

- F.W. Walbank state that Alexander the Great left "Macedonia under the command of Antipater, in case there was a rising in Greece." Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 200–201; Errington 1990, p. 58.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 201.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 201–203.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 204; see also Errington 1990, p. 44 for further details.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 204; see also Errington 1990, pp. 115–117 for further details.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 204; Adams 2010, p. 209; Errington 1990, pp. 69–70, 119.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 204–205; Adams 2010, pp. 209–210; Errington 1990, pp. 69, 119.

- ^ Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 205; see also Errington 1990, p. 118 for further details.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 208–209; Errington 1990, p. 117.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 210–211; Errington 1990, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 211; Errington 1990, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 211–212; Errington 1990, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 207 n. #1, 212; Errington 1990, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 212–213; Errington 1990, pp. 124–126.

- ^ a b Adams 2010, p. 213; Errington 1990, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 213–214; Errington 1990, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 214; Errington 1990, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 215.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 216.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 216–217; Errington 1990, p. 129.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 217; Errington 1990, p. 145.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 217; Errington 1990, pp. 145–147; Bringmann 2007, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Adams 2010, p. 218.

- ^ a b Bringmann 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 218; Errington 1990, p. 153.

- ^ a b Adams 2010, pp. 218–219; Bringmann 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 219; Bringmann 2007, p. 61; Errington 1990, p. 155;

Conversely, Errington dates Lysimachus' reunification of Macedonia by expelling Pyrrhus of Epirus as 284 BC, not 286 BC. - ^ a b Adams 2010, p. 219; Bringmann 2007, p. 61; Errington 1990, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 219; Bringmann 2007, p. 63; Errington 1990, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Errington 1990, p. 160.

- ^ Errington 1990, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 219; Bringmann 2007, p. 63; Errington 1990, pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b Adams 2010, pp. 219–220; Bringmann 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 219–220; Bringmann 2007, p. 63; Errington 1990, p. 164.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 220; Errington 1990, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b Adams 2010, p. 220.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 220; Bringmann 2007, p. 63; Errington 1990, p. 167.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 220; Errington 1990, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 221; see also Errington 1990, pp. 167–168 about the resurgence of Sparta under Areus I.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 221; Errington 1990, p. 168.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 221; Errington 1990, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 221; Errington 1990, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 221.

- ^ a b Adams 2010, p. 222.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 221–222; Errington 1990, p. 172.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 222; Errington 1990, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 222; Errington 1990, p. 173.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 222; Errington 1990, p. 174.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 223; Errington 1990, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b Adams 2010, p. 223; Errington 1990, p. 174.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 223; Errington 1990, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 223; Errington 1990, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 223–224; Eckstein 2013, p. 314; see also Errington 1990, pp. 179–180 for further details.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 223–224; Eckstein 2013, p. 314; Errington 1990, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 224.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 224; Eckstein 2013, p. 314; Errington 1990, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 224; see also Errington 1990, p. 182 about the Macedonian military's occupation of Sparta following the Battle of Sellasia.

- ^ Adams 2010, p. 224; Errington 1990, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Eckstein 2010, p. 229; Errington 1990, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Eckstein 2010, p. 229; Errington 1990, pp. 185–186, 189.

- ^ Eckstein 2010, pp. 229–230; see also Errington 1990, pp. 186–189 for further details;

Errington seems less convinced that Philip V at this point had any intentions of invading southern Italy via Illyria once the latter was secured, deeming his plans to be "more modest", Errington 1990, p. 189. - ^ Eckstein 2010, p. 230; Errington 1990, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Eckstein 2010, pp. 230–231; Errington 1990, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 79; Eckstein 2010, p. 231; Errington 1990, p. 192; also mentioned by Gruen 1986, p. 19.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 80; see also Eckstein 2010, p. 231 and Errington 1990, pp. 191–193 for further details.

- ^ Errington 1990, pp. 191–193, 210.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 82; Errington 1990, p. 193.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 82; Eckstein 2010, pp. 232–233; Errington 1990, pp. 193–194; Gruen 1986, pp. 17–18, 20.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 83; Eckstein 2010, pp. 233–234; Errington 1990, pp. 195–196; Gruen 1986, p. 21; see also Gruen 1986, pp. 18–19 for details on the Aetolian League's treaty with Philip V of Macedon and Rome's rejection of the second attempt by the Aetolians to seek Roman aid, viewing the Aetolians as having violated the earlier treaty.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 85; see also Errington 1990, pp. 196–197 for further details.

- ^ Eckstein 2010, pp. 234–235; Errington 1990, pp. 196–198; see also Bringmann 2007, p. 86 for further details.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 85–86; Eckstein 2010, pp. 235–236; Errington 1990, pp. 199–201; Gruen 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 86; see also Eckstein 2010, p. 235 for further details.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 86; Errington 1990, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 87; see also Errington 1990, pp. 202–203: "Roman desire for revenge and private hopes of famous victories were probably the decisive reasons for the outbreak of the war."

- ^ Eckstein 2010, pp. 233–235.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 87–88; Errington 1990, pp. 199–200; see also Eckstein 2010, pp. 235–236 for further details.

- ^ Eckstein 2010, p. 236.

- ^ a b Bringmann 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 88; Eckstein 2010, p. 236; Errington 1990, p. 203.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 88; Eckstein 2010, pp. 236–237; Errington 1990, p. 204.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 88–89; Eckstein 2010, p. 237.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 89–90; see also Eckstein 2010, p. 237 and Gruen 1986, pp. 20–21, 24 for further details.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 90–91; Eckstein 2010, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 91; Eckstein 2010, p. 238.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 91–92; Eckstein 2010, p. 238; see also Gruen 1986, pp. 30, 33 for further details.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 92; Eckstein 2010, p. 238.

- Thraciancoast as 183 BC, while Eckstein dates it as 184 BC.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 97; see also Errington 1990, pp. 207–208 for further details.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 97; Eckstein 2010, pp. 240–241; see also Errington 1990, pp. 211–213 for a discussion about Perseus' actions during the early part of his reign.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 97–98; Eckstein 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 98; Eckstein 2010, p. 240; Errington 1990, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 98–99; Eckstein 2010, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 98–99; see also Eckstein 2010, p. 242, who says that "Rome ... as the sole remaining superpower ... would not accept Macedonia as a peer competitor or equal."

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 99; Eckstein 2010, pp. 243–244; Errington 1990, pp. 215–216; Hatzopoulos 1996, p. 43.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 99; Eckstein 2010, p. 245; Errington 1990, pp. 204–205, 216; see also Hatzopoulos 1996, p. 43 for further details.

- ^ a b Bringmann 2007, pp. 99–100; Eckstein 2010, p. 245; Errington 1990, pp. 216–217; see also Hatzopoulos 1996, pp. 43–46 for further details.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, p. 104; Eckstein 2010, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 104–105; Eckstein 2010, p. 247; Errington 1990, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Bringmann 2007, pp. 104–105; Eckstein 2010, pp. 247–248; Errington 1990, pp. 203–205, 216–217.

Sources

- Adams, Winthrop Lindsay (2010). "Alexander's Successors to 221 BC". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 208–224. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Anson, Edward M. (2010). "Why Study Ancient Macedonia and What This Companion is About". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Badian, Ernst (1982). "Greeks and Macedonians". Studies in the History of Art. 10, SYMPOSIUM SERIES I. National Gallery of Art: 33–51. JSTOR 42617918.

- Bringmann, Klaus (2007) [2002]. A History of the Roman Republic. Translated by Smyth, W. J. Cambridge & Malden: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-3371-8.

- Buckley, Terry (1996). Aspects of Greek History, 750–323 BC: A Source-based Approach. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09957-9.

- Buckler, John (1989). Philip II and the Sacred War. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09095-8.

- ISBN 0-571-10958-6.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2010). "Macedonia and Rome, 221–146 BC". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 225–250. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2013). "Polybius, Phylarchus, and Historiographical Criticism". Classical Philology. 108 (4). The S2CID 164052948.

- ISBN 0-520-06319-8.

- Fox, Robin Lane (1980). The Search for Alexander. Boston: Little Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-29108-0.

- Gilley, Dawn L.; Worthington, Ian (2010). "Alexander the Great, Macedonia and Asia". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 186–207. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- ISBN 0-520-05737-6.

- ISBN 0-19-814815-1.

- Hatzopoulos, M. B. (1996). Macedonian Institutions Under the Kings: a Historical and Epigraphic Study. Vol. 1. Athens & Paris: Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity, National Hellenic Research Foundation; Diffusion de Boccard. ISBN 960-7094-90-5.

- Holt, Frank L. (1989). Alexander the Great and Bactria: the Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia. Leiden, New York, Copenhagen, Cologne: ISBN 90-04-08612-9.

- Holt, Frank L. (2012) [2005]. Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan. Berkeley, Los Angeles, & London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27432-7.

- Hornblower, Simon (2002) [1983]. The Greek World, 479–323 BC. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16326-9.

- King, Carol J. (2010). "Macedonian Kingship and Other Political Institutions". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 373–391. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Lewis, D.M.; Boardman, John (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Fourth Century B.C. (Volume 6). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4.

- Mollov, Ivelin A.; Georgiev, Dilian G. (2015). "Plovdiv". In Kelcey, John G. (ed.). Vertebrates and Invertebrates of European Cities:Selected Non-Avian Fauna. New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, & London: Springer. pp. 75–94. ISBN 978-1-4939-1697-9.

- Müller, Sabine (2010). "Philip II". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 166–185. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Olbrycht, Marck Jan (2010). "Macedonia and Persia". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 342–370. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Renault, Mary (2001) [1975]. The Nature of Alexander the Great. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-139076-X.

- Roisman, Joseph (2010). "Classical Macedonia to Perdiccas III". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 145–165. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Schwahn, Walther (1931). "Sympoliteia". Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft(in German). Vol. Band IV, Halbband 7, Stoa–Symposion. col. 1171–1266.

- Sprawski, Slawomir (2010). "The Early Temenid Kings to Alexander I". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 127–144. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Thomas, Carol G. (2010). "The Physical Kingdom". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 65–80. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Worthington, Ian (2008). Philip II of Macedonia. New Haven, CT: ISBN 978-0-300-12079-0.

Further reading

- Fox, Robin Lane. 2011. Brill's Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies In the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC-300 AD. Leiden: Brill.

- King, Carol J. 2018. Ancient Macedonia. New York: Routledge.

- Roisman, Joseph, and Ian Worthington. 2010. A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

External links

- Ancient Macedonia Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine at Livius, by Jona Lendering

- Twilight of the Polis and the rise of Macedon on YouTube (Philip, Demosthenes and the Fall of the Polis). Yale University courses, Lecture 24. (Introduction to Ancient Greek History)

- Heracles to Alexander The Great: Treasures From The Royal Capital of Macedon, A Hellenic Kingdom in the Age of Democracy, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford