History of Mumbai

This article's lead section may be too long. (June 2022) |

The islands suffered the

In 1960, following protests from the

Early history

Prehistoric period

Geologists believe that the coast of western India came into being around 100 to 80

Age of Dynastical Empires

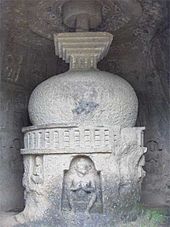

The islands were incorporated into the

The

Islamic period

The islands were under Muslim rule from 1348 to 1391. After the establishment of the Gujarat Sultanate in 1391, Muzaffar Shah I was appointed viceroy of north Konkan.[31] For the administration of the islands, he appointed a governor for Mahim. During the reign of Ahmad Shah I (1411–1443), Malik-us-Sharq was appointed governor of Mahim, and in addition to instituting a proper survey of the islands, he improved the existing revenue system of the islands. During the early 15th century, the Bhandaris seized the island of Mahim from the Sultanate and ruled it for eight years.[32] It was reconquered by Rai Qutb of the Gujarat Sultanate.[33] Firishta, a Persian historian, recorded that by 1429 the seat of government of the Gujarat Sultanate in north Konkan had transferred from Thane to Mahim.[34] On Rai Qutb's death in 1429–1430, Ahmad Shah I Wali of the Bahmani Sultanate of Deccan captured Salsette and Mahim.[35][36]

Ahmad Shah I retaliated by sending his son

In 1526, the Portuguese established their factory at Bassein.[43] During 1528–29, Lopo Vaz de Sampaio seized the fort of Mahim from the Gujarat Sultanate, when the King was at war with Nizam-ul-mulk, the emperor of Chaul, a town south of the islands.[44][45][46] Bahadur Shah had grown apprehensive of the power of the Mughal emperor Humayun and he was obliged to sign the Treaty of Bassein with the Portuguese on 23 December 1534. According to the treaty, the islands of Mumbai and Bassein were offered to the Portuguese.[47] Bassein and the seven islands were surrendered later by a treaty of peace and commerce between Bahadur Shah and Nuno da Cunha, Viceroy of Portuguese India, on 25 October 1535, ending the Islamic rule in Mumbai.[46]

Portuguese period

The Portuguese were actively involved in the foundation and growth of their religious orders in Bombay. The islands were leased to

The Portuguese encouraged intermarriage with the local population, and strongly supported the Roman Catholic Church.

The annexation of Portugal by

British period

Struggle with native powers

On 19 March 1662,

In 1737,

In 1782,

City development

The educational and economic progress of the city began with the Company's military successes in the Deccan. The

In 1838, the islands of

The

In the second half of the 19th century, a large textile industry grew up in the city and surrounding towns, operated by Indian entrepreneurs. Simultaneously a labour movement was organized. Starting with the Factory Act of 1881, state government played an increasingly important role in regulating the industry. The Bombay presidency set up a factory inspection commission in 1884. There were restrictions on the hours of children and women. An important reformer was Mary Carpenter, who wrote factory laws that exemplified Victorian modernization theory of the modern, regulated factory as vehicle of pedagogy and civilizational uplift. Laws provided for compensation for workplace accidents.[130]

Indian freedom movement

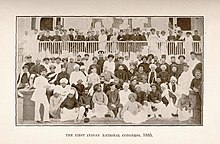

The growth of political consciousness started after the establishment of the Bombay Presidency Association on 31 January 1885.

The

Following World War I, which saw large movement of India troops, supplies, arms and industrial goods to and from Bombay, the city life was shut down many times during the

Independent India

20th century

After the

In the early 1960s, the

21st century

During the 21st century, the city suffered several bombings. On 6 December 2002, a bomb placed under a seat of an empty BEST (

Mumbai was lashed by torrential rains on

See also

- Bombay Before the British

- Growth of Mumbai

- Mumbai bombings

- List of forts in Mumbai

- List of governors of Bombay Presidency

- Timeline of Mumbai events

Notes

- ^ a b c d "History of Mumbai: Check Brief History, Origin, Colonial Reigns!". Testbook. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "NIRC". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Bombay: History of a City". British Library. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Geology

- ^ Ghosh 1990, p. 25

- ^ a b Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Geography

- ^ a b Ring, Salkin & Boda 1994, p. 142

- Daily News & Analysis. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 40

- ^ "Kanheri Caves". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ Abhilash Gaur (24 January 2004). "Pay dirt: Treasure amidst Mumbai's trash". The Tribune. India. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Ancient Period

- ^ Thana — Places of Interest 2000, Sopara

- Time Out Mumbai (6). 14 November 2008. Archived from the originalon 26 September 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 23

- ^ David 1973, p. 11

- ^ "The Slum and the Sacred Cave" (PDF). Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory (Columbia University). p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ a b Da Cunha 1993, p. 184

- ^ "World Heritage Sites — Elephanta Caves". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- Daily News & Analysis. Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ David 1973, p. 12

- ^ Nairne 1988, p. 15

- Express Group. Archived from the originalon 16 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- Express Group. Archived from the originalon 13 January 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, Early History

- ^ a b Da Cunha 1993, p. 34

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 36

- ^ O'Brien 2003, p. 3

- ^ Singh et al. 2004, p. 1703

- ^ a b Da Cunha 1993, p. 42

- ^ Prinsep, Thomas & Henry 1858, p. 315

- ^ Edwardes 1902, p. 54

- ^ a b c Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Muhammedan Period

- ^ Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Mediaeval Period

- ^ Misra 1982, p. 193

- ^ a b Misra 1982, p. 222

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 77

- ^ Edwardes 1902, p. 55

- ^ Edwardes 1902, p. 57

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1997, p. 110

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1997, p. 111

- ^ "The West turns East". Hindustan Times. India. Retrieved 12 August 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Maharashtra State Gazetteer 1977, p. 153

- ^ Edwardes 1993, p. 65

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 74

- ^ a b c d Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Portuguese Period

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 88

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 97

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Churches

- ^ a b Burnell 2007, p. 15

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 96

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 100

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 283

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 183

- ^ Baptista 1967, p. 25

- ^ a b c d e f Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 26

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, St. Andrews Church

- ^ Leonard 2006, p. 359

- ^ "The First Englishmen in Bombay". Department of Theoretical Physics (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research). Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Express Group. Archived from the originalon 24 July 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Catherine of Bragança (1638–1705)". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, Portuguese (1500–1670)

- ^ Malabari 1910, p. 98

- ^ Malabari 1910, p. 99

- ^ "12-Amazing Facts About Mumbai". Dozenfacts. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 272

- ^ a b Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, British Period

- ^ David 1973, p. 135

- ^ Murray 2007, p. 79

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 17

- ^ Shroff 2001, p. 169

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 31

- ^ a b Yimene 2004, p. 94

- ^ Colin C.Ganley (2007). "Security, the central component of an early modern institutional matrix; 17th century Bombay's Economic Growth" (PDF). International Society for New Institutional Economics (ISNIE): 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ Carsten 1961, p. 427

- ^ Hughes 1863, p. 227

- ^ Anderson 1854, p. 115

- Express Group. Archived from the originalon 12 April 2003. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Anderson 1854, p. 116

- Governor of Maharashtra. Archived from the originalon 23 September 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, St. Thomas Cathedral

- ^ Mehta 1940, p. 16

- ^ a b "Historical Perspective". Indian Navy. Retrieved 7 November 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, The Marathas

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 27

- ^ "The Wadias of India: Then and Now". Vohuman. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 32

- ^ "Fortifying colonial legacy". The Indian Express. 15 June 1997. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 28

- ^ Calcutta Magazine and Monthly Register 1832, p. 596

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, Acquisition, Changes, and Staff (Acquisition, 1774–1817

- ^ Kippis et al. 1814, p. 148

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 81

- ^ Segesta 2006, p. 32

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Journalism

- Express Group. Retrieved 2 February 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b Thana District Gazetteer 1984, Roads (Causeways)

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, English

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 54

- ^

"Battle of Khadki". Centre for Modeling and Simulation (University of Pune). Archived from the originalon 1 April 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Shona Adhikari (20 February 2000). "A mute testimony to a colourful age". The Tribune. India. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b c Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Growth of Bombay

- Asiatic Society of Bombay. Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "History". Elphinstone College. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Kanakalatha Mukund (3 April 2007). "Insight into the progress of banking". The Hindu. India. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Early Issues". Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "BMC allots Rs 14 cr to upgrade Mahim Causeway". The Times of India. India. 25 October 2008. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Grant Medical College and Sir J.J. Gr.of Hospitals. Archived from the originalon 20 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ a b Palsetia 2001, p. 189

- ^ Kidambi 2007, p. 163

- ^ "The South's first station". The Hindu. India. 26 February 2003. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "A City emerges". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 128

- University of Bombay. Archived from the originalon 23 October 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Banking

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Stock Exchange

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Jijamata Udyan

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 64

- ^ "Bombay Port Trust is 125". The Indian Express. 26 June 1997. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 131

- ^ "Tram-Car arrives". Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "History". Bombay Gymkhana. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Introduction". Bombay Stock Exchange. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Electricity arrives in Bombay". Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport (BEST). Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ "The Society". Bombay Natural History Society. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ a b "India Time Zones (IST)". Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ Sutherland & Shiffer 1884, p. 141

- ^ Aditya Sarkar, Trouble at the Mill: Factory Law and the Emergence of Labour Question in Late Nineteenth-Century Bombay (2017).

- ^ Banerjee 2006, p. 82

- ^ "Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit, first Baronet, 1823–1901". Vohuman. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Congress foundation day celebrated". The Hindu. India. 29 December 2006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ]

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 109

- ^ Dalal & Shah 2002, p. 30

- PDF, 124 KB). 139. Manushi: 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.)

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help - ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 74

- Time Out. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kidambi 2007, p. 118

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Municipal Corporation

- ^ "History". Haffkine Institute. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, pp. 175–7

- ^ Bagchi 2000, p. 233

- PDF, 163 KB) on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Agrawal & Bhatnagar 2005, p. 124

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 160

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Home Rule Movement

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Dawn of Gandhian Era

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Non Co-operation Movement

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Back Bay Scandal

- ^ Lalitha Sridhar (21 April 2001). "On the right track". The Hindu. India. Archived from the original on 21 January 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Daily News & Analysis. Archivedfrom the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Congress Session (of 1934)

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Businessmen and Civil Disobedience

- ^ Lala 1992, p. 98

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Economic Conditions (1933–1939)

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Outbreak of the War

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Quit India Movement

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Naval Mutiny

- ^ "A New Bombay, A new India". Hindustan Times. India. Archived from the original on 26 March 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Dawn of Independence

- ^ Alexander 1951, p. 65

- Mumbai Suburban District. Archived from the originalon 21 November 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ "The battle for Bombay". The Hindu. India. 13 April 2003. Archived from the original on 14 May 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Samyukta Maharashtra". Government of Maharashtra. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. Archivedfrom the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "Sons of soil: born, reborn". The Indian Express. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Gangadharan 1970, p. 123

- ^ Geeta Desai (13 May 2008). "BMC will give jobs to kin of Samyukta Maharashtra martyrs". Mumbai Mirror. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Sena fate: From roar to meow". The Times of India. India. 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "To the Present". Hindustan Times. India. Archived from the original on 26 March 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Banerjee 2005, p. 101

- ^ Heras Institute of Indian History and Culture 1983, p. 113

- ^ "Nehru Centre, Mumbai". Nehru Science Centre. Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "About Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA)". Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "General Information". Nehru Science Centre. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "About Navi Mumbai (History)". Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC). Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "The Great Mumbai Textile Strike... 25 Years On". Rediff.com India Limited. 18 January 2007. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Hansen 2001, p. 77

- ^ "Profile of Jawaharlal Nehru Custom House (Nhava Sheva)". Jawaharlal Nehru Custom House. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Naunidhi Kaur (5–18 July 2003). "Mumbai: A decade after riots". Frontline; the Hindu. 20 (14). India. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "1993: Bombay hit by devastating bombs". BBC. 12 March 1993. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Monica Chadha (12 September 2006). "Victims await Mumbai 1993 blasts justice". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Mumbai Travel Guide". Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Sheppard 1917, pp. 38, 104–105

- ^ William Safire (6 July 2006). "Mumbai Not Bombay". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Express Group. Retrieved 6 February 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Blast outside Ghatkopar station in Mumbai, 2 killed". rediff.com India Limited. 6 December 2002. Archived from the original on 11 August 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "1992: Mob rips apart mosque in Ayodhya". BBC. 6 December 1992. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "1 killed, 25 hurt in Vile Parle blast". The Times of India. India. 28 January 2003. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Fear after Bombay train blast". BBC. 14 March 2003. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Vijay Singh; Syed Firdaus Ashra (29 July 2003). "Blast in Ghatkopar in Mumbai, 4 killed and 32 injured". rediff.com India Limited. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "2003: Bombay rocked by twin car bombs". BBC. 25 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Maharashtra monsoon 'kills 200'". BBC. 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "At least 174 killed in Indian train blasts". CNN. 11 July 2006. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "India: A major terror target". The Times of India. India. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Rs 50, 000 not enough for injured". The Indian Express. 21 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "India police: Pakistan spy agency behind Mumbai bombings". CNN. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Daily News & Analysis. 16 February 2008. Archived from the originalon 3 June 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "North Indian taxi drivers attacked in Mumbai". NDTV. 29 March 2008. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "HM announces measures to enhance security" (Press release). Press Information Bureau (Government of India). 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- CNN-IBN. 13 July 2011. Archived from the originalon 14 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Mumbai-blasts-Death-toll-rises-to-26". Hindustan Times. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Death toll in Mumbai terror blasts rises to 19". NDTV. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

References

- Alexander, Horace Gundry (1951), New Citizens of India, Indian Branch, Oxford University Press

- Anderson, Philip (1854). The English in Western India. Smith and Taylor. ISBN 978-0-7661-8695-8. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- Bagchi, Amiya Kumar (2000). Private Investment in India, 1900–1939: Evolution of International Business, 1800–1945. Vol. V. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-19012-1. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Banerjee, Anil Chandra (2006). Indian Constitutional Documents −1757-1939. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-0792-2. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Banerjee, Sikata (2005). Make Me A Man!: Masculinity, Hinduism, And Nationalism in India. Suny Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6367-3. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Burnell, John (2007). Bombay in the Days of Queen Anne – Being an Account of the Settlement Also: Being an Account of the Settlement. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-5547-3. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Calcutta Magazine and Monthly Register. Vol. 33–36. S. Smith & Co. 1832. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- Carsten, F. L. (1961). The New Cambridge Modern History (Volume V: The ascendancy of France 1648–88). Vol. V. Cambridge University Press Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-04544-5. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Da Cunha, J.Gerson (1993). Origin of Bombay. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0815-1. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Dalal, Shilpa; Aparna Kaji Shah (2002). Bombay!. BPI (India). ISBN 978-81-7693-005-5.

- David, M. D. (1973), History of Bombay, 1661–1708, University of Bombay

- Dwivedi, Sharada; Rahul Mehrotra (1995), Bombay: The Cities Within, Eminence Designs

- Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth (1902). The Rise of Bombay: A Retrospect. Times of India Press.

- Baptista, Elsie Wilhelmina (1967), The East Indians: Catholic Community of Bombay, Salsette and Bassein, Bombay East Indian Association

- Gangadharan, K. K. (1970), Sociology of Revivalism: A Study of Indianization, Sanskritization, and Golwalkarism, Kalamkar Prakashan

- Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09264-8. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Greater Bombay District Gazetteer, Maharashtra State Gazetteers, vol. 27, Government of Maharashtra, 1960, archived from the original on 6 September 2008, retrieved 13 August 2008

- Greater Bombay District Gazetteer, Maharashtra State Gazetteers, vol. III, Government of Maharashtra, 1986, archived from the original on 9 March 2008, retrieved 15 August 2008

- Hansen, Thomas Blom (2001). Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08840-2. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Heras Institute of Indian History and Culture (1983), Indica, vol. 20, St. Xavier's College (Bombay)

- Hughes, William (1863), The geography of British history, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, retrieved 15 January 2009

- Sutherland, Joseph Myers; Richard J. Shiffer (1884). "International Conference Held at Washington for the Purpose of Fixing a Prime Meridian and a Universal Day. October, 1884 Protocols of the Proceedings". Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- Kidambi, Prashant (2007). The Making of an Indian Metropolis: Colonial Governance and Public Culture in Bombay, 1890–1920. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-5612-8. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Kippis, Andrew; William Godwin, George Robinson, G. G. and J. Robinson (1813). The New Annual Register, Or General Repository of History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1813. Pater-noster-Row. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lala, R. M (1992). Beyond the Last Blue Mountain: A Life of J.R.D. Tata. Viking. ISBN 9788184753318. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Leonard, Thomas M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-97662-6. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- Malabari, Phiroze B.M. (1910). Bombay in the making : Being mainly a history of the origin and growth of judicial institutions in the Western Presidency, 1661–1726 (PDF). London: T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- Mehta, Ashok (1940). "Indian Shipping: A Case Study of the Working of Imperialism" (PDF). N.t.Shroff Company Limited. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- "Portuguese Settlements on the Western Coast" (PDF). Maharashtra State Gazetteer. Government of Maharashtra. 1977. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Misra, Satish Chandra (1982), The Rise of Muslim Power in Gujarat: A History of Gujarat from 1298 to 1442, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers

- Murray, Sarah Elizabeth (2007). Moveable Feasts: From Ancient Rome to the 21st century, the Incredible Journeys of the Food We Eat. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-35535-7. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Nairne, Alexander Kyd (1988). History of the Konkan. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0275-5. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- O'Brien, Derek (2003). The Mumbai Factfile. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-302947-2.

- Palsetia, Jesse S. (2001). The Parsis of India: Preservation of Identity in Bombay City. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12114-0. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Prinsep, James; Henry Thoby Prinsep (1858). Essays on Indian Antiquities, Historic, Numismatic, and Palæographic, of the Late James Prinsep. Vol. 2. J. Murray. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Ring, Trudy; Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Segesta, Editrice (2006), Abitare

- Singh, K. S.; Bhanu, B. V.; Bhatnagar, B. R.; Bose, D. K.; Kulkarni, V. S.; Sreenath, J., eds. (2004). Maharashtra. Vol. XXX. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7991-102-0. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Sheppard, Samuel T (1917). Bombay Place-Names and Street-Names:An excursion into the by-ways of the history of Bombay City. Bombay, India: The Times Press. ASIN B0006FF5YU.

- Shroff, Zenobia E. (2001), The Contribution of Parsis to Education in Bombay City, 1820–1920, Himalaya Publishing House

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1997). The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64629-4. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Thana District Gazetteer, Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, vol. XIII, Government of Maharashtra, 1984 [1882], archived from the original on 12 August 2007, retrieved 10 November 2008

- Thana District Gazetteer, Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, vol. XIII, Government of Maharashtra, 1986 [1882], archived from the original on 14 February 2009, retrieved 15 August 2008

- Thana — Places of Interest, Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, vol. XIV, Government of Maharashtra, 2000 [1882], archived from the original on 9 August 2008, retrieved 14 August 2008

- Yimene, Ababu Minda (2004). An African Indian Community in Hyderabad: Siddi Identity, Its Maintenance and Change. Cuvillier Verlag. ISBN 3-86537-206-6. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Jagdish (1998). Bombay — Mumbai: A Picture Book. Wilco Publishing House. ISBN 81-87288-35-3.

- Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan. "Workers' politics and the mill districts in Bombay between the wars." Modern Asian Studies 15.3 (1981): 603-647 Online.

- Chaudhari, K.K (1987). "History of Bombay". Modern Period Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Contractor, Behram (1998). From Bombay to Mumbai. Oriana Books.

- Cox, Edmund Charles (1887). "Short History of Bombay Presidency". Thacker & Company.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Douglas, James (1900). Glimpses of old Bombay and western India, with other papers. Sampson Low, Marston & Co., London.

- ISBN 81-7223-216-0.

- Kooiman, Dick. "Jobbers and the emergence of trade unions in Bombay city." International Review of Social History 22.3 (1977): 313–328. online

- MacLean, James Mackenzie (1876). "A Guide to Bombay". Bombay Gazette Steam Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 978-0-375-40372-9.

- Morris, Morris David. The emergence of an industrial labor force in India: A study of the Bombay cotton mills, 1854-1947 (U of California Press, 1965).

- Patel, Sujata; Alice Thorner (1995). Bombay, Metaphor for Modern India. ISBN 0-19-563688-0.

- ISBN 0-670-88869-9.

- Sarkar, Aditya. Trouble at the Mill: Factory Law and the Emergence of Labour Question in Late Nineteenth-Century Bombay (Oxford UP, 2017) online review

- Sheppard, Samuel T. (1917). Bombay Place-names and Street-names: An excursion into the by-ways of the history of Bombay City. Times Press, Bombay.

- Tindall, Gillian (1992). City of Gold. ISBN 0-14-009500-4.

- Upadhaya, Sashibushan. Existence, Identity, and Mobilization: The Cotton Millworkers of Bombay, 1890-1919 (New Delhi: Manohar, 2004).

- Handbook of the Bombay Presidency: With an account of Bombay city. John Murray, London. 1881.

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Volume XXI). Government Central Press. 1884.

External links

- Portuguese India History: The Northern Province: Bassein, Bombay-Mumbai, Damao, Chaul from Dutch Portuguese Colonial History

- Century City Time Line – Bombay from Tate

- A collection of pages on Mumbai's History from Time Out(Mumbai)

- The Mumbai Project from Hindustan Times