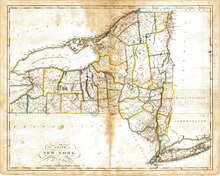

History of New York (state)

The history of New York begins around 10,000 B.C. when the first people arrived. By 1100 A.D. two main cultures had become dominant as the Iroquoian and Algonquian developed. European discovery of New York was led by the Italian Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524 followed by the first land claim in 1609 by the Dutch. As part of New Netherland, the colony was important in the fur trade and eventually became an agricultural resource thanks to the patroon system. In 1626, the Dutch thought they had bought the island of Manhattan from Native Americans.[1] In 1664, England renamed the colony New York, after the Duke of York and Albany, brother of King Charles II. New York City gained prominence in the 18th century as a major trading port in the Thirteen Colonies.

New York hosted significant transportation advancements in the 19th century, including the first

Due to New York City's trade ties to the South, there were numerous southern sympathizers in the early days of the

During the 19th century, New York City became the main entry point for European immigrants to the United States, beginning with a wave of Irish during their

The buildup of defense industries for World War II turned around the state's economy from the Great Depression, as hundreds of thousands worked to defeat the Axis powers. Following the war, the state experienced significant suburbanization around all the major cities, and most central cities shrank. The Thruway system opened in 1956, signaling another era of transportation advances.

Following a period of near-

Prehistory

The first peoples of New York are estimated to have arrived around 10,000 BC. Around AD 800,

The Iroquois established dominance over the fur trade throughout their territory, bargaining with European colonists. Other New York tribes were more subject to either European destruction or assimilation within the Iroquoian confederacy.[5] Situated at major Native trade routes in the Northeast and positioned between French and English zones of settlement, the Iroquois were intensely caught up with the onrush of Europeans, which is also to say that the settlers, whether Dutch, French or English, were caught up with the Iroquois as well.[6] Algonquian tribes were less united among their tribes; they typically lived along rivers, streams, or the Atlantic Coast.[7] But, both groups of natives were well-established peoples with highly sophisticated cultural systems; these were little understood or appreciated by the European colonists who encountered them. The natives had "a complex and elaborate native economy that included hunting, gathering, manufacturing, and farming...[and were] a mosaic of Native American tribes, nations, languages, and political associations."[3] The Iroquois usually met at an Onondaga in Northern New York, which changed every century or so, where they would coordinate policies on how to deal with Europeans and strengthen the bond between the Five Nations.

Tribes who have managed to call New York home have been the Iroquois, Mohawk,

Pre-colonial period

In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer in the service of the French crown, explored the Atlantic coast of North America between the Carolinas and Newfoundland, including New York Harbor and Narragansett Bay. On April 17, 1524, Verrazzano entered New York Bay, by way of the Strait now called the Narrows. He described "a vast coastline with a deep delta in which every kind of ship could pass" and he adds: "that it extends inland for a league and opens up to form a beautiful lake. This vast sheet of water swarmed with native boats". He landed on the tip of Manhattan and perhaps on the furthest point of Long Island.[10]

In 1535,

Dutch and British colonial period

On April 4, 1609, Henry Hudson, in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, departed Amsterdam in command of the ship Halve Maen (Half Moon). On September 3 he reached the estuary of the Hudson River.[12] He sailed up the Hudson River to about Albany near the confluence of the Mohawk River and the Hudson. His voyage was used to establish Dutch claims to the region and to the fur trade that prospered there after a trading post was established at Albany in 1614.

In 1614, the Dutch under the command of Hendrick Christiaensen, built Fort Nassau (now Albany) the first Dutch settlement in North America and the first European settlement in what would become New York.[13] It was replaced by nearby Fort Orange in 1623.[14] In 1625, Fort Amsterdam was built on the southern tip of Manhattan Island to defend the Hudson River.[15] This settlement grew to become the city New Amsterdam.

The British conquered New Netherland in 1664;[Note 1] Lenient terms of surrender most likely kept local resistance to a minimum. The colony and New Amsterdam were both renamed New York (and "Beverwijck" was renamed Albany) after its new proprietor, James II later King of England, Ireland and Scotland, who was at the time Duke of York and Duke of Albany[Note 2] The population of New Netherland at the time of English takeover was 7,000–8,000.[2][18]

Province of New York (1664–1776)

Thousands of poor German farmers, chiefly from the Palatine region of Germany, migrated to upstate districts after 1700. They kept to themselves, married their own, spoke German, attended Lutheran churches, and retained their own customs and foods. They emphasized farm ownership. Some mastered English to become conversant with local legal and business opportunities. They ignored the Indians and tolerated slavery (although few were rich enough to own a slave).[19]

Large

New York in the American Revolution

New York played a pivotal role in the Revolutionary War. The colony verged on revolt following the Stamp Act of 1765, advancing the New York City–based Sons of Liberty to the forefront of New York politics. The Act exacerbated the depression the province experienced after unsuccessfully invading Canada in 1760.[21] Even though New York City merchants lost out on lucrative military contracts, the group sought common ground between the King and the people; however, compromise became impossible as of April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord. In that aftermath the New York Provincial Congress on June 9, 1775, for five pounds sterling for each hundredweight of gunpowder delivered to each county's committee.[22]

Two powerful families had for decades assembled colony-wide coalitions of supporters. With few exceptions, members long associated with the DeLancey faction went along when its leadership decided to support the crown, while members of the Livingston faction became Patriots.[23][24]

New York's strategic central location and port made it key to controlling the colonies. The British assembled the century's largest fleet: at one point 30,000

In October 1777, American General Horatio Gates won the Battle of Saratoga, later regarded as the war's turning point. Had Gates not held, the rebellion might well have broken down: losing Saratoga would have cost the entire Hudson–Champlain corridor, which would have separated New England from the rest of the colonies and split the future union.[25]

Statehood to the Civil War

Upon war's end, New York's borders became well–defined: the counties east of Lake Champlain became Vermont

Many Iroquois supported the British (typically fearing future American ambitions). Many were killed during the war; others went into exile with the British. Those remaining lived on twelve reservations; by 1826 only eight reservations remained, all of which survived into the 21st century.

The state adopted

In 1785, New York City became the national capital and continued as such on and off until 1790; George Washington was

In the early 19th century, New York became a center for advancement in transportation. In 1807, Robert Fulton initiated a steamboat line from New York to Albany, the first successful enterprise of its kind.[28] By 1815, Albany was the state's turnpike center,[29] which established the city as the hub for pioneers migrating west to Buffalo and the Michigan Territory.[30]

In 1825 the

Advancing transportation quickly led to settlement of the fertile Mohawk and Gennessee valleys and the Niagara Frontier. Buffalo and Rochester became boomtowns. Significant migration of New England "Yankees" (mainly of English descent) to the central and western parts of the state led to minor conflicts with the more settled "Yorkers" (mainly of German, Dutch, and Scottish descent). More than 15% of the state's 1850 population had been born in New England [citation needed]. The western part of the state grew fastest at this time. By 1840, New York was home to seven of the nation's thirty largest cities.[Note 4]

During this period, towns established academies for education, including for girls. The western area of the state was a center of progressive causes, including support of abolitionism, temperance, and women's rights. Religious enthusiasms flourished and the Latter Day Saint movement was founded in the area by Joseph Smith and his vision. Some supporters of abolition participated in the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves reach freedom in Canada or in New York.

In addition, in the early 1840s the state legislature and Governor William H. Seward expanded rights for free blacks and fugitive slaves in New York: in 1840 the legislature passed laws protecting the rights of African Americans against Southern slave-catchers.[33] One guaranteed alleged fugitive slaves the right of a jury trial in New York to establish whether they were slaves, and another pledged the aid of the state to recover free blacks kidnapped into slavery,[34] (as happened to Solomon Northup of Saratoga Springs in 1841, who did not regain freedom until 1853.) In 1841 Seward signed legislation to repeal a "nine-month law" that allowed slaveholders to bring their slaves into the state for a period of nine months before they were considered free. After this, slaves brought to the state were immediately considered freed, as was the case in some other free states. Seward also signed legislation to establish public education for all children, leaving it up to local jurisdictions as to how that would be supplied (some had segregated schools).[35]

New York culture bloomed in the first half of the 19th century: in 1809

New York in the American Civil War

A civil war was not in the best interest of business, because New York had strong ties to the Deep South, both through the port of New York and manufacture of cotton goods in upstate textile mills. Half of New York City's exports were related to cotton before the war. Southern businessmen so frequently traveled to the city that they established favorite hotels and restaurants. Trade was based on moving Southern goods. The city's large Democrat community feared the impact of Abraham Lincoln's election in 1860 and the mayor urged secession of New York.

By the time of the 1861 Battle of Fort Sumter, such political differences decreased and the state quickly met Lincoln's request for soldiers and supplies. More soldiers fought from New York than any other Northern state. While no battles were waged in New York, the state was not immune to Confederate conspiracies, including one to burn various New York cities and another to invade the state via Canada.[39]

In January 1863, Lincoln issued the

End of the Civil War to 1901

In the following decades, New York strengthened its dominance of the

Immigration increased throughout the latter half of the 19th century. Starting with refugees from the

New York's political pattern changed little after the mid–19th century. New York City and its metropolitan area was already heavily Democrat; Upstate was aligned with the Republican Party and was a center of abolitionist activists. In the 1850s, Democratic

1901 through the Great Depression

By 1901, New York was the richest and most populous state. Two years prior, the

The state was serviced by over a dozen major railroads and at the start of the 20th century and electric Interurban rail networks began to spring up around Syracuse, Rochester and other cities in New York during this period.[48][49]

In the late 1890s governor Theodore Roosevelt and fellow Republicans such as Charles Evans Hughes worked with many Democrats such as Al Smith to promote Progressivism.[50] They battled trusts and monopolies (especially in the insurance industry), promoted efficiency, fought waste, and called for more democracy in politics. Democrats focused more on the benefits of progressivism for their own ethnic working class base and for labor unions.[51][52]

Democratic political machines, especially Tammany Hall in Manhattan, opposed woman suffrage because they feared that the addition of female voters would dilute the control they had established over groups of male voters. By the time of the New York State referendum on women's suffrage in 1917, however, some wives and daughters of Tammany Hall leaders were working for suffrage, leading it to take a neutral position that was crucial to the referendum's passage.[53][54]

Following a sharp but short-lived Depression at the beginning of the decade,

World War II and the modern era

As the largest state, New York again supplied the most resources during

World War II constituted New York's last great industrial era. At its conclusion, the defense industry shrank and the economy shifted towards producing services rather than goods. Returning soldiers disproportionately displaced female and minority workers who had entered the industrial workforce only when the war left employers no other choice.[60] Companies moved to the south and west, seeking lower taxes and a less costly, non–union workforce. Many workers followed the jobs.[61] The

Larger cities stopped growing around 1950. Growth resumed only in New York City, in the 1980s. Buffalo's population fell by half between 1950 and 2000. Reduced immigration and worker migration led New York State's population to decline for the first time between 1970 and 1980. California and Texas both surpassed it in population.[citation needed]

New York entered its third era of massive transportation projects by building

The

Last decades of 20th century

In the late 20th century,

This in turn led to a surge in culture. New York City became, once again, "the center for all things chic and trendy".

New York City increased its already large share of

Upstate did not fare as well as downstate; the major industries that began to reinvigorate New York City did not typically spread to other regions. The number of farms in the state had fallen to 30,000 by 1997. City populations continued to decline while suburbs grew in area, but did not increase proportionately in population.

21st century (2001–present day)

In 2001, New York entered a new era following the

Following the attacks, plans were announced to rebuild the World Trade Center site. 7 World Trade Center became the first World Trade Center skyscraper to be rebuilt in five years after the attacks. One World Trade Center, four more office towers, and a memorial to the casualties of the September 11 attacks are under construction as of 2011. One World Trade Center opened on November 3, 2014.[64]

On October 29 and 30, 2012,

See also

- Historical outline of New York

- History of New York City

- History of the mid-Atlantic states

Notes

- ^ The takeover is commonly said to have been part of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. But, this war was not officially declared until 1665; the Dutch and British were at peace when the attack was made.[16]

- ^ James Stuart (1633–1701), brother and successor of Charles II, was both the Duke of York and Duke of Albany before being crowned James II of England and James VII of Scotland in 1685.[17]

- Anglicized form of the Dutch Rensselaerswijck. The patroonship was confirmed as an English manor by Charles II in 1664.[20]

- ^ New York City (1st at 312,710), Brooklyn (7th at 36,233), Albany (9th at 33,721), Rochester (19th at 20,191), Troy (21st at 19,334), Buffalo (22nd at 18,213), Utica (29th at 12,782).[32]

- ^ By comparison, New York's population in 1890 was just over 5 million.[44]

References

- ISBN 9780738509143.

- ^ a b Eisenstadt 2005, p. xx

- ^ a b Klein 2001, p. 3

- ^ Horatio Gates Spafford, LL.D. A Gazetteer of the State of New-York, Embracing an Ample Survey and Description of Its Counties, Towns, Cities, Villages, Canals, Mountains, Lakes, Rivers, Creeks and Natural Topography. Arranged in One Series, Alphabetically: With an Appendix… (1824), at Schenectady Digital History Archives, selected extracts, accessed 28 December 2014

- ^ Klein 2001, pp. 6–7

- ^ Nash, Gary B. Red, White and Black: The Peoples of Early North America Los Angeles 2015. Chapter 1, p. 8

- ^ Klein 2001, p. 7

- ^ "EARLY INDIAN MIGRATION IN OHIO". GenealogyTrails.com. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Pritzker 441

- ^ Centro Studi Storici Verrazzano Archived 2009-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0-7565-0122-9

- ^ Nevius, Michelle and James, "New York's many 9/11 anniversaries: the Staten Island Peace Conference", Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2012-9-24.

- ^ "One of America's First Cities: Colonial Albany". Albany Institute of History and Art. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Cuyler (1906). Albany Chronicles: A History of the City Arranged Chronologically. J.B. Lyon Company. p. 18.

fort nassau albany.

- ^ Goodwin, Maud Wilder (1897). Fort Amsterdam in the days of the Dutch. New York: The Knickerbocker press. pp. 239–240.

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, p. 1053 (article: "New Netherland")

- ^ "James II". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ a b c "New York". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- ^ Philip Otterness, Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York (2004)

- ^ Reynolds, Cuyler (1906). Albany Chronicles: A History of the City Arranged Chronologically, From the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. Albany: J. B. Lyon Company. p. 66.

- ^ Klein (2001), p. 202

- ^ Middletown Times-Press, March 19, 1918, page 4

- ^ N. E. H. Hull, Peter C. Hoffer and Steven L. Allen, "Choosing Sides: A Quantitative Study of the Personality Determinants of Loyalist and Revolutionary Political Affiliation in New York," Journal of American History, (1978) 65#2 pp. 344–366 in JSTOR esp. pp 347, 354, 365

- ^ Joyce D. Goodfriend, Who Should Rule at Home?: Confronting the Elite in British New York City (Cornell University Press, 2017).

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. xxi–xxii

- ^ a b c Eisenstadt 2005, p. xxii

- ^ Lamb, Martha J., ed. (1886). The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Vol. XV. New York City: Historical Publication Co. p. 124. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ McEneny 2006, p. 92

- ^ McEneny 2006, p. 75

- ^ Albany. (2010). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 10, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "History of Railroads in New York State". New York State Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (1840). "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1840". United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ISBN 978-0-684-82490-1.

- Project MUSE.

- ^ Finkelman, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, p. 798 (article: "Irving, Washington")

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, p. 359 (article: "Cole, Thomas")

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, p. xxiv

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 335–337 (article: "Civil War")

- ISBN 978-0-226-31774-8. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Eisenstadt 2005, p. xxv

- ISBN 978-0-345-47639-5.

- ^ a b Eisenstadt 2005, p. 498 (article: "Ellis Island")

- 2000 United States Census. United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved 2010-09-18. (page 1 of the document, page 31 of the file)

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, p. 1473 (article: "Statue of Liberty")

- ^ a b Eisenstadt 2005, p. xxvi

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 1417–1418 (article: "Skyscrapers")

- ^ Beauchamp, Rev. William Martin (1908). Past and present of Syracuse and Onondaga county, New York (Volume 1). New York: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1908, pg. 489. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ "Certification Review" (PDF). Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council, November 2002. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Richard L. McCormick, From Realignment to Reform: Political Change in New York State, 1893–1910 (1981).

- ^ Robert F. Wesser, A response to progressivism: The Democratic Party and New York politics, 1902–1918 (1986).

- ^ Irwin Yellowitz, Labor and the Progressive Movement in New York State, 1897–1916 (1965).

- ^ Eleanor Flexner Century of Struggle (1959), pp. 247, 282, 290

- ^ Ronald Schaffer, "The New York City Woman Suffrage Party, 1909–1919." New York History (1962): 269-287. in JSTOR

- ^ Vernon, J.R. (July 1991). "The 1920–21 deflation: the role of aggregate supply". Economic Inquiry. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 1102–1103 (article: "New York Stock Exchange")

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 1334–1335 (article: "Roosevelt, Franklin Delano")

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.111

- ^ "World War 2 Casualty Statistics". Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 1726–1728 (article: "World War II")

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eisenstadt 2005, p. xxvii

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 1100–1102

- ^ Eisenstadt 2005, pp. 1395–1401 (article: "September 11th, 2001")

- ^ "One World Trade Center". The Skyscraper Center. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ Jeff Stone & Maria Gallucci (October 29, 2014). "Hurricane Sandy Anniversary 2014: Fortifying New York—How Well Armored Are We For The Next Superstorm?". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ Robert S. Eshelman (November 15, 2012). "ADAPTATION: Political support for a sea wall in New York Harbor begins to form". E&E Publishing, LLC. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

Bibliography

- Broxmeyer, Jeffrey D. Electoral Capitalism: The Party System in New York's Gilded Age. of Pennsylvania Press, 2020) covers city and state.

- Curran, Robert Emmett, ed. Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915 (2012) excerpt and text search

- Dearstyne, Bruce W., The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History (Albany: Excelsior Editions, 2015). xxiv, 359 pp.

- Eisenstadt, Peter, ed. (2005). The Encyclopedia of New York State. Syracuse, New York: ISBN 0-8156-0808-X.

- Ellis, David M.; James A. Frost; Harold C. Syrett; Harry J. Carman (1967) [1957]. A History of New York State. LCCN 67020587..

- Fox, Dixon Ryan. The decline of aristocracy in the politics of New York (1918) online.

- Ingalls, Robert P. Herbert H. Lehman and New York's Little New Deal (1975) on 1930s online

- Kammen, Michael (1996) [1975]. Colonial New York: a History. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510779-9.

- Klein, Milton M. (ed.) and the ISBN 0-8014-3866-7.

- Otterness, Philip. Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York (2004) 235 pp.

- Wesser, Robert F. A response to progressivism : the Democratic Party and New York politics, 1902-1918 (1986) online

Regions and cities

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (1998), 1300 of highly detailed scholarly history

- Goldman, Mark. High Hopes: The Rise and Decline of Buffalo, New York (Suny Press, 1983)

- ISBN 1-892724-53-7.