History of North Macedonia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| History of North Macedonia |

|---|

|

| Chronological |

|

| Topical |

| Related |

| Lists and outlines |

|

|

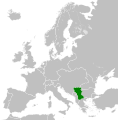

The history of North Macedonia encompasses the history of the territory of the modern state of North Macedonia.

Prehistory

Ancient period

Paeonians and other tribes

In antiquity, most of the territory that is now

Persian rule

In the late 6th century BC, the

Macedon and Rome

In 336 BC Philip II of Macedon fully annexed Upper Macedonia, including its northern part and southern Paeonia, which both now lie within North Macedonia.[11] Philip's son Alexander the Great conquered most of the remainder of the region, incorporating it in his empire, with exclusion of Dardania. The Romans included most of the Republic in their province of Macedonia, but the northernmost parts (Dardania) lay in Moesia; by the time of Diocletian, they had been subdivided, and the Republic was split between Macedonia Salutaris and Moesia prima.[12] Little is known about the Slavs before the 5th century CE.

Medieval period

Migration Period

At this period the area divided from the

In the late 7th century

Contested between various realms

Use of the name "Sklavines" as a nation on its own was discontinued in Byzantine records after circa 836 as those Slavs in the Macedonia region became a population in the

At the end of the 10th century, much of what is now

Dobromir Chrysos rebelled against the emperor and after an unsuccessful imperial campaign in autumn 1197, the emperor sued for peace and recognized Dobromir-Chrysus' rights to lands between the Strymon and Vardar, including Strumica and the fortress of Prosek.[15]

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Byzantine control was punctuated by periods of

During the period in the 12th, 13th and early 14th century, parts of modern western North Macedonia were under the rule of the Albanian Noble Gropa family, which ruled territories between Ohrid and Debar. The city of Debar and some other territories after the ending rule of Gropa Noble family, were ruled by the Albanian Royal House of Kastrioti which ruled the Principality of Kastrioti during the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century. After the death of the Albanian Prince Gjon Kastrioti in 1437, many parts of his domains were conquered by the Ottoman Empire and shortly after this, during the 15th century were again restored into the Albanian rule of League of Lezhë led by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. During this period, western territories of modern North Macedonia became battleground between the Albanian and Ottoman armies. Some of the battles that took place in the territory of Macedonia were the Battle of Polog, Battle of Mokra, Battle of Ohrid, Battle of Otonetë, Battle of Oranik and many others. Skanderbeg's Campaign into Macedonia also took place. With the death of Skanderbeg on 17 January 1468 the Albanian Resistance began to fall. After the death of Skanderbeg the Albanian League was led by Lekë Dukagjini, but it did not have the same success as before and the last Albanian strongholds were conquered in 1479 in the Siege of Shkodër.

Ottoman period

Conquered by the Ottoman army at the end of the 14th century,

During the period of Ottoman rule the region gained a substantial

During the period of Bulgarian National Revival (1762–1878), many Bulgarians from Vardar Macedonia supported the struggle for creation of Bulgarian cultural educational and religious institutions, including the Bulgarian Exarchate. The subsequent Macedonian Struggle (1893–1908) remained inconclusive.

Karađorđević period (1912–1944)

Balkan Wars and World War I

The region was captured by the

-

Skopje after being captured by Albanian revolutionaries who defeated the Ottoman forces holding the city in August 1912.

-

The Kingdom of Serbia in 1914, on the eve of World War I

-

Map showing Yugoslavia in 1919 in the aftermath of World War I before the treaties of Neuilly, Trianon and Rapallo[24]

-

Provinces of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1920–1922

Royal Yugoslav period

After World War I (1914–1918) the Slavs in Serbian Macedonia ("

In 1925,

On 6 January 1929, king Alexander I Karađorđević committed a coup d'état and installed the so-called 6 January Dictatorship, abolishing the Vidovdan Constitution and renaming the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It was divided into provinces called banovinas. The territory of Vardar Banovina had Skopje as its capital and it included what eventually became modern North Macedonia (plus some lands north of it that are now part of Serbia and Kosovo). Alexander's dictatorship effectively ruined parliamentary democracy, and after growing popular resentment against the king's autocratic rule, he was assassinated in 1934 in France by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).

World War II

During World War II, the Vardar Banovina was occupied between 1941 and 1944 by Italian-ruled Albania, which annexed the Albanian-populated western regions, and pro-German Bulgaria, which occupied the remainder. The occupying powers persecuted those inhabitants of the province who opposed the regime; this prompted some of them to join the Communist resistance movement of Josip Broz Tito. However, the Bulgarian army was well received by most of the population when it entered Macedonia[26] and it was able to recruit from the local population, which formed as much as 40% to 60% of the soldiers in certain battalions.

Socialist Yugoslav period

1944–1949

Following World War II, Yugoslavia was reconstituted as a federal state under the leadership of Tito's

Greece was concerned by the initiatives of the Yugoslav government, as they were seen as a pretext for future territorial claims against the Greek region of

During the

1950–1990

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

Independence

1990s

In 1990, the form of

On 8 September 1991, the country held an

Following the

Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the new Macedonian state under its constitutional name. However, international recognition of the new country was delayed by Greece's objection to the use of what it considered a Hellenic name and national symbols, as well as controversial clauses in the Republic's constitution, a controversy known as the Macedonia naming dispute. To compromise, the country was admitted to the United Nations under the provisional name of "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" on 8 April 1993.[30]

Greece was still dissatisfied and it imposed a trade blockade in February 1994. The sanctions were lifted in September 1995 after Macedonia changed its flag and aspects of its constitution that were perceived as granting it the right to intervene in the affairs of other countries. The two neighbours immediately went ahead with normalizing their relations, but the state's name remains a source of local and international controversy. The usage of each name remains controversial to supporters of the other.

After the state was admitted to the United Nations under the temporary reference "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", other international organisations adopted the same convention. More than half of the UN's member states have recognized the country as the Republic of Macedonia, including the United States of America while the rest use the temporary reference "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" or have not established any diplomatic relations with the country.

In 1999, the

In end the war, Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević reached an agreement with NATO which allowed refugees to return under UN protection. However, the war increased tensions, and relations between Macedonians and the Albanian minority became strained. On the positive side, Athens and Ankara presented a united front of 'non-involvement'. In Greece, there was a strong reaction against NATO and the United States.

2000s

In the spring of 2001, ethnic Albanian insurgents calling themselves the National Liberation Army (some of whom were former members of the Kosovo Liberation Army) took up arms in the north and northwest of the Republic of Macedonia. They demanded that the constitution be rewritten to enshrine certain Albanian minority interests such as language rights. The guerillas received support from Albanians in NATO-controlled Kosovo and Albanian guerrillas in the demilitarized zone between Kosovo and the rest of Serbia. The fighting was concentrated in and around Tetovo, the fifth largest city in the country, and in the wider regions of Skopje, the capital, and Kumanovo, the third largest city.

After a joint NATO-Serb crackdown on Albanian guerrillas in Kosovo, European Union (EU) officials were able to negotiate a cease-fire in June. The government would give to the citizens of Albanian descent greater civil rights, and the guerrilla groups would voluntarily relinquish their weapons to NATO monitors. This agreement was a success, and in August 2001 3,500 NATO soldiers conducted "Operations Essential Harvest" to retrieve the arms. Directly after the operation finished in September the NLA officially dissolved itself. Ethnic relations have since improved significantly, although hardliners on both sides have been a continued cause for concern and some low level violence continues particularly directed against police.

On 26 February 2004, President

In March 2004, the country submitted an application for membership of the European Union, and on 17 December 2005 was listed by the EU Presidency conclusions as an accession candidate (as "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia"). However, accession proceedings were delayed due to opposition by Greece until the 2018 resolution of the Macedonia naming dispute, and later by Bulgaria due to unresolved differences between the two countries on the history of the region and what is perceived as "anti-Bulgarian ideology".[31][32]

2010s–2020s

In June 2017, Zoran Zaev of Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) became new Prime Minister six months after early elections. The new center-left government ended 11 years of conservative VMRO-DPMNE rule led by former Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski.[33]

In June 2018, the

Stevo Pendarovski (SDSM) was sworn in as North Macedonia's new president in May 2019.[35] The early parliamentary elections took place on 15 July 2020.[36] Zoran Zaev has served as the Prime Minister of the Republic of North Macedonia again since August 2020.[37] Prime Minister Zoran Zaev announced his resignation after his party, the Social Democratic Union, suffered losses in local elections in October 2021.[38] After internal party leadership elections, Dimitar Kovačevski succeeded him as leader of the SDSM on 12 December 2021,[39] and was sworn in as Prime Minister of North Macedonia on 16 January 2022, securing a 62–46 confidence vote in Parliament for his new SDSM-led coalition cabinet.[40]

See also

- Breakup of Yugoslavia

- History of Albania

- History of the Balkans

- History of Bulgaria

- History of Europe

- History of Greece

- History of Kosovo

- History of Serbia

- History of Turkey

- History of Yugoslavia

- Macedonia (region)

- Macedonian nationalism

- United Macedonia

- Military history of North Macedonia

- Independent State of Macedonia

- League of Communists of Yugoslavia

- President of the Republic of North Macedonia

- List of prime ministers of North Macedonia

- List of presidents of Yugoslavia

- List of prime ministers of Yugoslavia

- Politics of North Macedonia

References

- ISBN 0-8108-3336-0.

- Brown, Keith (2003). The Past in Question : Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- Dalibor Jovanovski, "Greek Historiography and the Balkan Wars", On Macedonian Matters. From the partition and annexation of Macedonia in 1913 to the present (Verlag Otto Sagner: Munich, Berlin, 2015). http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/38056455/dalibor_statija.pdf [archive]

Notes

- ISBN 0-393-05974-X, page 518: "... Italy; to the north, Thracian tribes known collectively as the Paeonians."

- ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 49.

- ISBN 0-520-03177-6.

- ISBN 1-84162-186-2, p. 13

- ISBN 0-691-00880-9, pp. 74-75.

- ISBN 0-521-23348-8, pp. 723-724.

- ISBN 0-521-23447-6, page 284

- ISBN 9781930053564. p. 239

- ISBN 9781444351637. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Persian influence on Greece (2)". Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ISBN 1-85065-534-0, p. 14.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica — Scopje

- ^ "Archived copy". img53.exs.cx. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ http://assets.cambridge.org/97805217/70170/excerpt/9780521770170_excerpt.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Paul Stephenson, Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204, Cambridge University Press, 29 iun. 2000, p.307

- ISBN 1443888494, p. 2.

- ^ "North Macedonia | History, Geography, & Points of Interest". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- )

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica – Rumelia at Encyclopædia Britannica.com

- ^ The Encyclopædia Britannica, or, Dictionary of arts, sciences ..., Volume 19. 1859. p. 464.

- ^ Walter Pohl. (p. 13-24 in: Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings, Ed. Lester K. Little and Barbara H. Rosenwein, Blackwell Publishers, 1998)Ethnic boundaries are not static, and even less so in a period of migrations. It is possible to change one's ethnicity... Even more frequently, in the Early Middle Ages, people lived under circumstances of ethnic ambiguity.

- ISBN 0-472-11414-X. Pg 3 most South Slavs mentioned with specific national-type names mentioned in our sources were such by political affiliation, namely that the individuals named so served the given state's ruler, and cannot be considered ethnic Serbs, Croats or whatever

- ^ Note that this map does not reflect any internationally established borders or armistice lines – it only reflect opinion of the researchers from London Geographical Institute about issue how final borders should look after the Paris Peace Conference.

- ^ The British Foreign Office and Macedonian National Identity, 1918-1941, Andrew Rossos' Slavic Review, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), pp. 369-394 [1]

- ^ Marshall Lee Miller, Bulgaria During the Second World War, Stanford University Press, 1975, p.123

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Faculty of Law, University of Skopje Archived 30 June 2012 at archive.today (in Macedonian)

- President of the Republic of Macedonia – The Official Site of The President of the Republic of Macedonia Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A/RES/47/225. Admission of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to membership in the United Nations". Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Marusic, Sinisa Jakov (10 October 2019). "Bulgaria Sets Tough Terms for North Macedonia's EU Progress Skopje". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Bulgaria sends memorandum to the Council on North Macedonia". Radio Bulgaria. 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Macedonia gets new government six months after elections | DW | 01.06.2017". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "North Macedonia name change enters force | DW | 12.02.2019". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "North Macedonia's new president Stevo Pendarovski takes office". 12 May 2019.

- ^ "EM North Macedonia: Review of the 2020 parliamentary elections in North Macedonia".

- ^ "President of the Government of the Republic of North Macedonia – Zoran Zaev". 11 May 2018.

- ^ "North Macedonia Prime Minister Zoran Zaev resigns | DW | 31.10.2021". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "North Macedonia Ruling Party Elects Dimitar Kovacevski as Leader". Balkan Insight. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "North Macedonia's Lawmakers Elect Dimitar Kovacevski As New PM". Radio Free Europe. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

Further reading

- Mattioli, Fabio (2020). Dark Finance: Illiquidity and Authoritarianism at the Margins of Europe. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-1294-5.

External links

- The Mariovo in Macedonia, 1564: Mariovo People and Macedonia.

- New Power – Federated Yugoslavia

- History of Macedonia: Primary Documents

- Discover Macedonia – Discover North Macedonia on Facebook

![Map showing Yugoslavia in 1919 in the aftermath of World War I before the treaties of Neuilly, Trianon and Rapallo[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Jugo-slavia%2C_1919.png/115px-Jugo-slavia%2C_1919.png)