History of Trier

Trier in Rhineland-Palatinate, whose history dates to the Roman Empire, is the oldest city in Germany. Traditionally it was known in English by its French name of Treves.

Prehistory

The first traces of human settlement in the area of the city show evidence of

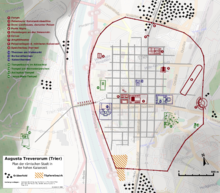

Roman Empire

The

Trier rose in importance during the

A

From 318 onwards Trier was the seat of the

From 367 under

Roman Trier had been subjected to attacks by

Middle Ages

By the end of the 5th century, Trier was under

Many

Medieval legend, recorded in 1105 in the Gesta Treverorum, makes Trebeta son of Ninus the founder of Trier.[20] Also of medieval date is the inscription at the facade of the Red House of Trier market,

- ANTE ROMAM TREVIRIS STETIT ANNIS MILLE TRECENTIS.

- PERSTET ET ÆTERNA PACE FRVATVR. AMEN.

- ("Thirteen hundred years before Rome, Trier stood / may it stand on and enjoy eternal peace, amen.")

being mentioned in the Codex Udalrici of 1125.

From 902, when power passed into the hands of the archbishops, Trier was administered by the

Elected in 1307 when he was only 22 years old, Baldwin was the most important Archbishop and Prince-Elector of Trier in the Middle Ages. He was the brother of the German King and Emperor Henry VII and his grandnephew Charles would later become German King and Emperor as Charles IV. He used his family connections to add considerable territories to the Electorate of Trier and is also known to have built many castles in the region. When he died in 1354, Trier was a prospering city.[22]

The status of Trier as an archbishopric city was confirmed in 1364 by Emperor Charles IV and by the Reichskammergericht; the city's dream of self-rule came definitively to an end in 1583. Until the demise of the old empire, Trier remained the capital of the electoral Archbishopric of Trier, although not the residence of its head of state, the Prince-Elector. At its head was a court of lay assessors, which was expanded in 1443 by Archbishop Jacob I to include bipartisan mayors.[23]

The Dombering (curtain wall of the cathedral) having been secured at the end of the 10th century, Archbishop

Modern age

In 1473, Emperor

From 1581 until 1593, intense witch persecutions, involving nobility as well as commoners, abounded throughout this region, leading to mass executions of hundreds of people.

In the 17th century, the Archbishops and Prince-Electors of Trier relocated their residences to

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) did initially not touch Trier. Warfare reached the city as part of the French–Habsburg rivalry and the conflict between townspeople and the archbishop Philipp Christoph von Sötern. The city asked the Spanish government in Luxemburg for help against the bishop's absolutist tendencies in 1630. While Spain sent troops and installed a garrison, the bishop used the aid of French troops to regain Trier two times in 1632 and 1645, interrupted by a surprise Spanish attack in 1635 and 10 years of Spanish occupation and imprisonment of the bishop, an event that served as a pretext to start the Franco-Spanish War. The cathedral chapter finally disempowered the bishop in 1649 using mercenaries and Lorrain troops against the bishop's French auxiliary forces.[26]

Trier experienced peace until 1673 when

During the

With the peace treaties of

In 1814, the French era ended suddenly as Trier was taken by

The influential philosopher and revolutionary

From 1840 on, the situation of Trier began to improve as the neighbouring state of

During the

Second World War

In September 1944 during the

According to research by the historian Adolf Welter, at least 420 people were killed in the December 1944 attacks on Trier. Numerous buildings were damaged. During the entire war, 1,600 houses in the city were completely destroyed.

On March 2, 1945, the city surrendered to the

Postwar period

At the end of April 1969, the old Roman road at the Porta Nigra was uncovered. Shortly afterward, on May 12, 1969, the open-air wildlife enclosure in the Weisshaus forest was opened. The University of Trier was reestablished in 1970, initially as part of the combined university of Trier-Kaiserslautern. The evolution of Trier as a university city took a further step forward with the opening on April 1, 1974, of the Martinskloster student residence halls. In 1975, the university once more became independent.[31]

Other significant events of the 1970s include the discontinuation of the 99-year-old "Trierische Landeszeitung" newspaper on March 31, 1974, and the reopening of the restored

From May 24 to 27 1984, Trier officially celebrated its 2,000th anniversary. In 1986, Roman Trier (the

From April 22 to October 24, 2004, the State Garden Show was held on the Petrisberg heights and attracted 724,000 visitors.[33]

A new discovery of Roman remains was made in April 2006, when traces of building walls were unearthed during demolition works in the city centre.

A large exhibition on the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great was the largest exhibition in Trier up to date. It ran from the 2nd of June to the 4th of November 2007. Some 1,600 pieces lend by 160 museums in 20 countries were on exhibit in three museums in Trier. In all 353,974 tickets were sold and all three museums counted 799,034 visitors, making it one of the most successful exhibitions in Germany.[34] The Ehrang/Quint district of Trier was heavily damaged and flooded during the July 16, 2021 floods of Germany, Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Incorporation of municipalities

Formerly autonomous municipalities and territories that have been incorporated into the city of Trier. Some localities had already formed part of the urban area between 1798 and 1851. In 1798, the city area covered a total of 8.9 square kilometres.[35]

| Year | Localities |

|---|---|

| 1888 | St. Paulin, Maar, Zurlauben, Löwenbrücken, St. Barbara |

| 1888 | Separation of Heiligkreuz and Olewig |

| 1912 | Pallien (southern part), Heiligkreuz, St. Matthias, St. Medard, Feyen (with Weismark) |

| 1930 | Euren, Biewer, Pallien (northern part), Kürenz, Olewig |

| June 7, 1969 | Ehrang-Pfalzel (formed on March 1, 1968, through unification of the two previously autonomous municipalities) |

| June 7, 1969 | Eitelsbach, Filsch, Irsch, Kernscheid, Ruwer, Tarforst, Zewen |

Population development

At the beginning of the 4th century AD, Trier was the residence of the Roman Emperor and, with an estimated 80,000 inhabitants, the largest city north of the

The Second World War cost Trier roughly 35% of its population (30,551 people) and the number of inhabitants had dropped to 57,000 by 1945. Only through the incorporation of several surrounding localities into the city on June 7, 1969, did the population once more reach its prewar level. This reorganisation in fact pushed the number of inhabitants beyond the 100,000 mark, which accorded the city of Trier Großstadt status. On June 30, 2005, the population of Trier according to official records of the Rhineland-Palatinate state authorities was 99,685 (registered only by Hauptwohnsitz and after comparison with other regional authorities).

The following overview illustrates the city's different population levels, according to the current size of the city area. Up until 1801, these figures are mostly estimates; after this date they have been sourced from census results or official records of state authorities. From 1871 onwards, these statistics correspond to the "present population", from 1925 to the "resident population" and from 1987 to the "population resident at main domicile". Prior to 1871, the population was recorded using inconsistent survey methods.

|

|

|

¹ Census figure[36]

Notes

- ^ See: Heinen, pp. 1-12.

- ^ See: Heinen, pp. 30-55.

- ^ Paul Stephenson, Constantine, Roman Emperor, Christian Victor 2010: :"Trier" 124ff.

- ^ a b Stephenson 2010:124.

- ^ See: Heinen, pp. 327-347.

- ^ See: Heinen, pp. 211-265.

- ^ See: Kuhnen, pp. 135-142.

- ^ A coin of 314 was found in a construction trench (Stephenson 2010:125).

- ^ See: Dehio, p. 1031.

- ^ See: Kuhnen, pp. 114-121. See also: Dehio, pp. 1033-1051.

- ^ Preserved in Trier's Diocesan Museum; Stephenson 2010:125 and fig. 25.

- ^ ISBN 9789077922736. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ See: Heinen, pp. 366-384.

- ^ Romance speakers in Mosella valley & Trier; p.14 (in Italian)

- ^ See: Anton / Haverkamp, pp. 22-67.

- ^ See: Dehio, pp. 1054-1057.

- ^ See: Dehio, pp. 1057-1063.

- ISBN 978-1-349-61839-2.

- ^ See: Petzold, pp. 36-39.

- ^ See: Petzold, p. 82.

- ^ See: Anton / Haverkamp, pp. 239-293.

- ^ See: Anton / Haverkamp, pp. 295-315.

- ^ See: Anton / Haverkamp, pp. 570-579.

- ^ See: Petzold, p. 43.

- ^ See: Anton / Haverkamp, pp. 531-552.

- ^ Wagner, Paul (1888), "Philipp Christoph v. Sötern", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 26, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 50–69

- ^ See: Petzold, pp. 101-103.

- ^ See: Petzold, pp. 73-96.

- ^ See: Petzold, pp. 128-131; See also: Welter, 1939-1945 pp. 115-119 and the site on historicum.net listed under external links

- ^ See: Christoffel, pp. 468-511; See also: Welter, Neue Forschungsergebnisse, pp. 41-83 and the site on historicum.net listed under external links

- ^ See: Heise, pp. 107-192.

- ^ Stadt Trier - City of Trier - La Ville de Trèves Archived 2012-07-13 at archive.today

- ^ Landesgartenschau Trier 2004

- ^ Konstantin-Ausstellung

- ^ See: Petzold, pp. 137-157.

- ^ StLA RLP - Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz Archived 2010-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

Literature

- Christoffel, Edgar: Krieg am Westwall 1944/45. Trier, Akademische Buchhandlung 1989. ISBN 3-88915-033-0

- Clemens, Gabriele; Clemens; Lukas: Geschichte der Stadt Trier. Munich 2007, ISBN 3-406-55618-3.

- Dehio, Georg: Handbuch der deutschen Kunstdenkmäler: Rheinland-Pfalz, Saarland. 2nd revised edition, Munich, ISBN 3-422-00382-7

- Gwatkin, William E. Jr. (October 1933). "Roman Trier". The Classical Journal. 29 (1): 3–12.

- Heise, Karl A.: Die alte Stadt und die neue Zeit. Stadtplanung und Denkmalpflege Triers im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Trier, Paulinus 1999. ISBN 3-87760-107-3

- King, Anthony: Roman Gaul and Germany (Exploring the Roman World). University of California Press 1990. ISBN 0-520-06989-7

- Kuhnen, Hans-Peter (ed.): Das roemische Trier. Stuttgart, Konrad Theiss 2001. ISBN 3-923319-85-1

- Monz, Heinz (ed.): Trierer biographisches Lexikon. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier 2000. ISBN 3-88476-400-4

- Petzold, Hans (ed.): Trier - 2000 Jahre Stadtentwicklung. Katalog zur Ausstellung Tuchfabrik Weberbach 6.5. - 10.11.1984. Ed. by Baudezernat der Stadt Trier. Trier, City printing office 1984.

- Resmini, Bertram: Das Erzbistum Trier (Germania Sacra, Vol. 31). Walter De Gruyter Inc. 1993. ISBN 3-11-013657-0

- Schnitzius, Sebastian: Entwicklung der Eisenbahn im Trierer Raum. Trier, Deutsche Bundesbahn 1984.

- Trier. Augustusstadt der Treverer. Stadt und Land in vor- und fruehroemischer Zeit. 2nd ed. Mainz 1984, ISBN 3-8053-0792-6.

- Universitaet Trier: 2000 Jahre Trier. 3 volumes, Spee-Verlag, Trier.

- Heinz Heinen: Trier und das Trevererland in roemischer Zeit. 1985, ISBN 3-87760-065-4.

- Hans-Hubert Anton / ISBN 3-87760-066-2.

- Kurt Duewell / Franz Irsigler (ed.): Trier in der Neuzeit. 1988, ISBN 3-87760-067-0.

- Heinz Heinen: Trier und das Trevererland in roemischer Zeit. 1985,

- Welter, Adolf: Die Luftangriffe auf Trier 1939-1945. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Trierer Landes. Trierer Muenzfreunde 1995. ISBN 3-923575-13-0

- Welter, Adolf: Die Luftangriffe auf Trier im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Trierer Muenzfreunde 2001. ISBN 3-923575-19-X

- Welter, Adolf: Trier 1939-1945. Neue Forschungsergebnisse zur Stadtgeschichte. Trier 1998

- Welter, Adolf: Bild-Chronik Trier in der Besatzungszeit 1918-1930. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Trierer Landes. Trierer Muenzfreunde 1992. ISBN 3-923575-11-4

- Welter, Adolf: Der Flugplatz Trier-Euren. Vom kaiserlichen Exerzierfeld zum heutigen Industriegebiet. Trierer Muenzfreunde 2004. ISBN 3-923575-20-3

- Wightman, Edith M.: Roman Trier and the Treveri. London, Brecon 1970. ISBN 0-246-63980-6

- Zenz, Emil: Die Stadt Trier im 20. Jahrhundert, 1. Haelfte 1900-1950. Trier, Spee 1981. ISBN 3-87760-608-3

- Zuche, Thomas (ed.): Stattfuehrer – Trier im Nationalsozialismus. 3rd ed. 1997. ISBN 3-87760-057-3

There is not much literature in English on Trier. The three volumes on Trier's history published by the history department of the University of Trier between 1985 and 1996 represent a complete history including all researches up to the time when they were published. Clemens' 2007 book (Clemens is a history professor of Trier University, earlier he worked at the Roman Museum in Trier) can be viewed as an update.

External links

- Official website of the City of Trier with some historical information

- History of the diocese of Trier (in German)

- The Bombings of Trier 1943-1945 at historicum.net (in German)

- website of the Roman Museum (Landesmuseum Trier) (in German)

- website of the Municipal Museum Simeonstift (Stadtmuseum Simeonstift Trier) (in German and French)

- website of the museum of the diocese of Trier (Bischoefliches Dom- und Dioezesanmuseum) (in German)

- website of the Karl-Marx-House museum

- website of the Toys Museum (Spielzeugmuseum Trier) (in German)