History of botany

The history of botany examines the human effort to understand life on Earth by tracing the historical development of the discipline of botany—that part of natural science dealing with organisms traditionally treated as plants.

Rudimentary botanical science began with empirically based plant lore passed from generation to generation in the oral traditions of

In Europe, botanical science was soon overshadowed by a

In Europe, the

Progressively more sophisticated scientific technology has aided the development of contemporary botanical offshoots in the plant sciences, ranging from the applied fields of economic botany (notably agriculture, horticulture and forestry), to the detailed examination of the structure and function of plants and their interaction with the environment over many scales from the large-scale global significance of vegetation and plant communities (biogeography and ecology) through to the small scale of subjects like cell theory, molecular biology and plant biochemistry.

Introduction

Within botany, there are a number of sub-disciplines that focus on particular plant groups, each with their own range of related studies (anatomy, morphology etc.). Included here are:

Ancient knowledge

Nomadic hunter-gatherer societies passed on, by oral tradition, what they knew (their empirical observations) about the different kinds of plants that they used for food, shelter, poisons, medicines, for ceremonies and rituals etc. The uses of plants by these pre-literate societies influenced the way the plants were named and classified—their uses were embedded in folk-taxonomies, the way they were grouped according to use in everyday communication.[4] The nomadic life-style was drastically changed when settled communities were established in about twelve centres around the world during the Neolithic Revolution which extended from about 10,000 to 2500 years ago depending on the region. With these communities came the development of the technology and skills needed for the domestication of plants and animals and the emergence of the written word provided evidence for the passing of systematic knowledge and culture from one generation to the next.[5]

Plant lore and plant selection

During the Neolithic Revolution, plant knowledge increased most obviously through the use of plants for food and medicine. All of today's

It is also from the Neolithic, in about 3000 BC, that we glimpse the first known illustrations of plants

Early botany

Ancient India

An early example of ancient Indian plant classification is found in the

Classical antiquity

Classical Greece

Ancient Athens, of the 6th century BC, was the busy trade centre at the confluence of

Theophrastus and the origin of botanical science

Foremost among the scholars studying botany was Theophrastus of Eressus (Greek: Θεόφραστος; c. 371–287 BC) who has been frequently referred to as the "Father of Botany". He was a student and close friend of Aristotle (384–322 BC) and succeeded him as head of the Lyceum (an educational establishment like a modern university) in Athens with its tradition of peripatetic philosophy. Aristotle's special treatise on plants — θεωρία περὶ φυτῶν — is now lost, although there are many botanical observations scattered throughout his other writings (these have been assembled by Christian Wimmer in Phytologiae Aristotelicae Fragmenta, 1836) but they give little insight into his botanical thinking.[15] The Lyceum prided itself in a tradition of systematic observation of causal connections, critical experiment and rational theorizing. Theophrastus challenged the superstitious medicine employed by the physicians of his day, called rhizotomi, and also the control over medicine exerted by priestly authority and tradition.[16] Together with Aristotle, he had tutored Alexander the Great whose military conquests were carried out with all the scientific resources of the day, the Lyceum garden probably containing many botanical trophies collected during his campaigns as well as other explorations in distant lands.[17] It was in this garden where he gained much of his plant knowledge.[18]

Enquiry into Plants and Causes of Plants

Theophrastus's major botanical works were the :

We must consider the distinctive characters and the general nature of plants from the point of view of their morphology, their behaviour under external conditions, their mode of generation and the whole course of their life.

— Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants

The Enquiry is 9 books of "applied" botany dealing with the forms and

Pedanius Dioscorides

A full synthesis of ancient Greek pharmacology was compiled in De Materia Medica c. 60 AD by Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40-90 AD) who was a Greek physician with the Roman army. This work proved to be the definitive text on medicinal herbs, both oriental and occidental, for fifteen hundred years until the dawn of the European Renaissance being slavishly copied again and again throughout this period.[24] Though rich in medicinal information with descriptions of about 600 medicinal herbs, the botanical content of the work was extremely limited.[25]

Ancient Rome

The Romans contributed little to the foundations of botanical science laid by the ancient Greeks, but made a sound contribution to our knowledge of applied botany as agriculture. In works titled De Re Rustica, four Roman writers contributed to a compendium Scriptores Rei Rusticae, published from the Renaissance on, which set out the principles and practice of agriculture. These authors were Cato (234–149 BC), Varro (116–27 BC) and, in particular, Columella (4–70 AD) and Palladius (4th century AD).[26]

Pliny the Elder

Roman encyclopaedist

Ancient China

In

Medieval knowledge

Medicinal plants of the early Middle Ages

In Western Europe, after Theophrastus, botany passed through a bleak period of 1800 years when little progress was made and, indeed, many of the early insights were lost. As Europe entered the Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries), China, India and the Arab world enjoyed a golden age.

Medieval China

Chinese philosophy had followed a similar path to that of the ancient Greeks. Between 100 and 1700 AD, many new works on pharmaceutical botany were produced. The 11th century scientists and statesmen Su Song and Shen Kuo compiled learned treatises on natural history, emphasising herbal medicine.[29] Among the pharmaceutical botany works were encyclopaedic accounts and treatises compiled for the Chinese imperial court. These were free of superstition and myth with carefully researched descriptions and nomenclature; they included cultivation information and notes on economic and medicinal uses — and even elaborate monographs on ornamental plants. But there was no experimental method and no analysis of the plant sexual system, nutrition, or anatomy.[30]

Medieval India

In India, simple artificial plant classification systems of the

Islamic Golden Age

The 400-year period from the 9th to 13th centuries AD was the

The Silk Road

Following the fall of Constantinople (1453), the newly expanded Ottoman Empire welcomed European embassies in its capital, which in turn became the sources of plants from those regions to the east which traded with the empire. In the following century, twenty times as many plants entered Europe along the Silk Road as had been transported in the previous two thousand years, mainly as bulbs. Others were acquired primarily for their alleged medicinal value. Initially, Italy benefited from this new knowledge, especially Venice, which traded extensively with the East. From there, these new plants rapidly spread to the rest of Western Europe.[35] By the middle of the sixteenth century, there was already a flourishing export trade of various bulbs from Turkey to Europe.[36]

The Age of Herbals

In the European

The authors of the oldest herbals of the 16th century, Brunfels, Fuchs, Bock, Mattioli and others, regarded plants mainly as the vehicles of medicinal virtues. ... Their chief object was to discover the plants employed by the physicians of antiquity, the knowledge of which had been lost in later times. The corrupt texts of Theophrastus, Dioscorides, Pliny and Galen had been in many respects improved and illustrated by ... Italian commentators of the 15th and ... early part of the 16th century; but there was one imperfection which no criticism could remove,—the highly unsatisfactory descriptions of the old authors or the entire absence of descriptions.[38]

It was moreover at first assumed that the plants described by the Greek physicians must grow wild in Germany also, and generally in the rest of Europe; each author identified a different native plant with some one mentioned by Dioscorides or Theophrastus or others, and thus there arose [in] the 16th century a confusion of nomenclature.[38]

However, the need for accurate and detailed plant descriptions meant that some herbals were more botanical than medicinal.

A great advance was made by the first German composers of herbals, who went straight to nature, described the wild plants growing around them and had figures of them carefully executed in wood. Thus was made the first beginning of a really scientific examination of plants, though the aims pursued were not yet truly scientific, for no questions were proposed as to the nature of plants, their organisation or mutual relations; the only point of interest was the knowledge of individual forms and of their medicinal virtues.[39]

— Julius von Sachs, History of Botany

German Otto Brunfels's (1464–1534) Herbarum Vivae Icones (1530) contained descriptions of about 47 species new to science combined with accurate illustrations. His fellow countryman Hieronymus Bock's (1498–1554) Kreutterbuch of 1539 described plants he found in nearby woods and fields and these were illustrated in the 1546 edition.[40] However, it was Valerius Cordus (1515–1544) who pioneered the formal botanical description that detailed both flowers and fruits, some anatomy including the number of chambers in the ovary, and the type of ovule placentation. He also made observations on pollen and distinguished between inflorescence types.[40] His five-volume Historia Plantarum was published about 18 years after his early death aged 29 in 1561–1563. In England, William Turner (1515–1568) in his Libellus De Re Herbaria Novus (1538) published names, descriptions and localities of many native British plants[41] and in Holland Rembert Dodoens (1517–1585), in Stirpium Historiae (1583), included descriptions of many new species from the Netherlands in a scientific arrangement.[42]

Herbals contributed to botany by setting in train the science of plant description, classification, and botanical illustration. Up to the 17th century, botany and medicine were one and the same but those books emphasising medicinal aspects eventually omitted the plant lore to become modern pharmacopoeias; those that omitted the medicine became more botanical and evolved into the modern compilations of plant descriptions we call Floras. These were often backed by specimens deposited in a herbarium which was a collection of dried plants that verified the plant descriptions given in the Floras. The transition from herbal to Flora marked the final separation of botany from medicine.[43]

The Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment (1550–1800)

The revival of learning during the European Renaissance renewed interest in plants. The church, feudal aristocracy and an increasingly influential merchant class that supported science and the arts, now jostled in a world of increasing trade. Sea voyages of exploration returned botanical treasures to the large public, private, and newly established botanic gardens, and introduced an eager population to novel crops, drugs and spices from Asia, the East Indies and the New World.

The number of scientific publications increased. In England, for example, scientific communication and causes were facilitated by learned societies like Royal Society (founded in 1660) and the

During the 18th century, botany was one of the few sciences considered appropriate for genteel educated women. Around 1760, with the popularization of the Linnaean system, botany became much more widespread among educated women who painted plants, attended classes on plant classification, and collected herbarium specimens although emphasis was on the healing properties of plants rather than plant reproduction which had overtones of sexuality. Women began publishing on botanical topics and children's books on botany appeared by authors like

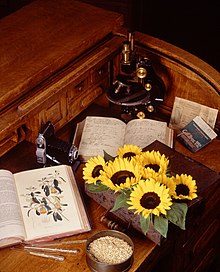

Botanical gardens and herbaria

Public and private gardens have always been strongly associated with the historical unfolding of botanical science.[51] Early botanical gardens were physic gardens, repositories for the medicinal plants described in the herbals. As they were generally associated with universities or other academic institutions, the plants were also used for study. The directors of these gardens were eminent physicians with an educational role as "scientific gardeners" and it was staff of these institutions that produced many of the published herbals.

The botanical gardens of the modern tradition were established in northern Italy, the first being at Pisa (1544), founded by Luca Ghini (1490–1556). Although part of a medical faculty, the first chair of materia medica, essentially a chair in botany, was established in Padua in 1533. Then in 1534, Ghini became Reader in materia medica at Bologna University, where Ulisse Aldrovandi established a similar garden in 1568 (see below).[52] Collections of pressed and dried specimens were called a hortus siccus (garden of dry plants) and the first accumulation of plants in this way (including the use of a plant press) is attributed to Ghini.[53][54] Buildings called herbaria housed these specimens mounted on card with descriptive labels. Stored in cupboards in systematic order, they could be preserved in perpetuity and easily transferred or exchanged with other institutions, a taxonomic procedure that is still used today.

By the 18th century, the physic gardens had been transformed into "order beds" that demonstrated the classification systems that were being devised by botanists of the day — but they also had to accommodate the influx of curious, beautiful and new plants pouring in from voyages of exploration that were associated with European colonial expansion.

From Herbal to Flora

Plant classification systems of the 17th and 18th centuries now related plants to one another and not to man, marking a return to the non-anthropocentric botanical science promoted by Theophrastus over 1500 years before. In England, various herbals in either Latin or English were mainly compilations and translations of continental European works, of limited relevance to the British Isles. This included the rather unreliable work of Gerard (1597).[55] The first systematic attempt to collect information on British plants was that of Thomas Johnson (1629),[56][57] who was later to issue his own revision of Gerard's work (1633–1636).[58]

However, Johnson was not the first apothecary or physician to organise botanical expeditions to

In France, Clusius journeyed throughout most of

This approach coupled with the new Linnaean system of binomial nomenclature resulted in plant encyclopaedias without medicinal information called Floras that meticulously described and illustrated the plants growing in particular regions.[66] The 17th century also marked the beginning of experimental botany and application of a rigorous scientific method, while improvements in the microscope launched the new discipline of plant anatomy whose foundations, laid by the careful observations of Englishman Nehemiah Grew[67] and Italian Marcello Malpighi, would last for 150 years.[68]

Botanical exploration

More new lands were opening up to European colonial powers, the botanical riches being returned to European botanists for description. This was a romantic era of botanical explorers, intrepid

Classification and morphology

By the middle of the 18th century, the botanical booty resulting from the era of exploration was accumulating in gardens and herbaria – and it needed to be systematically catalogued. This was the task of the taxonomists, the plant classifiers.

Plant classifications have changed over time from "artificial" systems based on general habit and form, to pre-evolutionary "natural" systems expressing similarity using one to many characters, leading to post-evolutionary "natural" systems that use characters to infer evolutionary relationships.[70]

Italian physician

To sharpen the precision of description and classification,

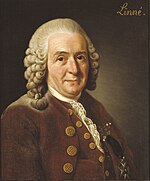

Above all it was Swedish

18th century plant taxonomy bequeathed to the 19th century a precise binomial nomenclature and botanical terminology, a system of classification based on natural affinities, and a clear idea of the ranks of family, genus and species — although the taxa to be placed within these ranks remains, as always, the subject of taxonomic research.

Anatomy

In the first half of the 18th century, botany was beginning to move beyond descriptive science into experimental science. Although the

Physiology

In plant physiology, research interest was focused on the movement of sap and the absorption of substances through the roots.

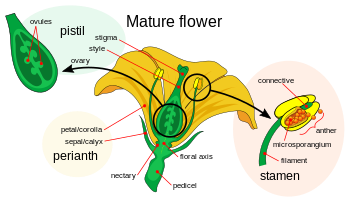

Plant sexuality

It was Rudolf Camerarius (1665–1721) who was the first to establish plant sexuality conclusively by experiment. He declared in a letter to a colleague, dated 1694 and titled De Sexu Plantarum Epistola, that "no ovules of plants could ever develop into seeds from the female style and ovary without first being prepared by the pollen from the stamens, the male sexual organs of the plant".[86]

Some time later, the German academic and natural historian