History of the United States Merchant Marine

| Part of a series on |

| U.S. Maritime History |

|---|

The maritime history of the United States is a broad theme within the history of the United States. As an academic subject, it crosses the boundaries of standard disciplines, focusing on understanding the United States' relationship with the oceans, seas, and major waterways of the globe. The focus is on merchant shipping, and the financing and manning of the ships. A merchant marine owned at home is not essential to an extensive foreign commerce. In fact, it may be cheaper to hire other nations to handle the carrying trade than to participate in it directly. On the other hand, there are certain advantages, particularly during time of war, which may warrant an aggressive government encouragement to the maintenance of a merchant marine.[1]

History

Early history

The

The 18th century

As British colonists before 1776, American merchant vessels had enjoyed the protection of the Royal Navy. Major ports in the Northeast began to specialize in merchant shipping. The main cargoes included tobacco, as well as rice, indigo and naval stores from the Southern colonies. From the other colonies exports included horses, wheat, fish and lumber. By the 1760s New England was the center of a flourishing shipbuilding industry. Imports included all manner of manufactured goods.[3]

Revolutionary War

The first war that an organized United States Merchant Marine took part in was the

1783–1790

By 1783, however, with the end of the Revolution, America became solely responsible for the safety of its own commerce and citizens. Without the means or the authority to field a naval force necessary to protect their ships in the Mediterranean against the

Also in 1784, Boston navigators sailed to the Pacific Northwest and opened the U.S. fur trade.[5]

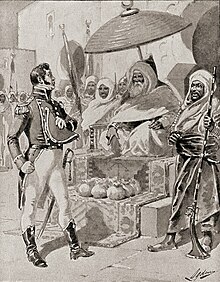

In 1785, the Dey of Algiers took two American ships hostage and demanded US$60,000 in ransom for their crews. Then-ambassador to France Thomas Jefferson argued that conceding the ransom would only encourage more attacks. His objections fell on the deaf ears of an inexperienced American government too riven with domestic discord to make a strong show of force overseas. The U.S. paid Algiers the ransom, and continued to pay up to $1 million per year over the next 15 years for the safe passage of American ships or the return of American hostages. Payments in ransom and tribute to the privateering states amounted to 20 percent of United States government annual revenues in 1800.[4]

Jefferson continued to argue for cessation of the tribute, with rising support from George Washington and others. With the recommissioning of the American navy in 1794 and the resulting increased firepower on the seas, it became more and more possible for America to say "no", although by now the long-standing habit of tribute was hard to overturn. A largely successful undeclared war with French privateers in the late 1790s showed that American naval power was now sufficient to protect the nation's interests on the seas.[4] These tensions led to the First Barbary War in 1801.

The only clause in the treaty of peace (1783) concerning commerce was a stipulation guaranteeing that the navigation of the Mississippi should be forever free to the United States. John Jay at this time had tried to secure some reciprocal trade provisions with Great Britain, but without result. Pitt in 1783 introduced a bill into the British Parliament providing for free trade between the United States and the British colonies, but instead of passing this bill Parliament enacted the British Navigation Act of 1783 which admitted only British-built ships and crewed ships to the ports of the West Indies and imposed heavy tonnage dues upon American ships in other British ports. This was amplified in 1786 by another act designed to prevent the fraudulent registration of American vessels, and by still another in 1787 which prohibited the importation of American goods by way of foreign islands. The favorable features of the old Navigation Acts which had granted bounties and reserved the English markets in certain cases to colonial products were gone; the unfavorable alone were left. The British market was further curtailed by the depression there after 1783. Although the French treaty of 1778 had promised "perfect equality and reciprocity" in commercial relations, it was found impossible to make a commercial treaty upon this basis. Spain demanded as her price for reciprocal trading relations that the United States surrender for twenty-five years the right of navigating the Mississippi, a price which the New England merchants would have been glad to pay. France (1778) and the Dutch Republic (1782) made treaties, but not on even terms; Portugal refused the U.S. advances. Only Sweden (1783) and Prussia (1785) made treaties guaranteeing reciprocal commercial privileges.[6]

The weakness of Congress under the Articles of Confederation prevented retaliation by the central government. Power was repeatedly asked to regulate commerce, but was refused by the states, upon whom rested the carrying out of such commercial treaties as Congress might negotiate. Eventually the states themselves attempted retaliatory measures, and during the years 1783–88, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia levied tonnage dues upon British vessels or discriminating tariffs upon British goods. Whatever effect these efforts might have had were neutralized by the fact that the duties were not uniform, varying in different states from no tariffs whatever to duties of 100 percent. This simply drove British ships to the free or cheapest ports and their goods continued to flood the market. Commercial war between the states followed and turned futility into chaos.[6]

The effect of this trade policy upon American shipping was detrimental. After the passage of the U.S. Constitution in 1789 the congress was petitioned for relief. On June 5, 1789, a petition from the tradesmen and manufacturers of Boston was sent to the Congress which stated "that the great decrease of American manufactures, and almost total stagnation of American ship-building, urge us to apply to the sovereign Legislature of these States for their assistance to promote these important branches, so essential to our national wealth and prosperity. It is with regret we observe the resources of this country exhausted for foreign luxuries, our wealth expended for various articles which could be manufactured among ourselves, and our navigation subject to the most severe restrictions in many foreign ports, whereby the extensive branch of American ship-building is essentially injured, and a numerous body of citizens, who were formerly employed in its various departments, deprived of their support and dependence.... ""[7] The congress responded with passage of the Tariff of 1789 which established tonnage rates favorable to American carriers by charging them lower cargo fees than those imposed on foreign boats importing similar goods. Coastal trade was reserved exclusively for American flag vessels.

In 1789, when the Constitution was adopted, the registered tonnage of the United States engaged in foreign trade was 123,893. During the next succeeding eight years it increased 384 percent.[8] I

The 1790s

In 1790, federal legislation was enacted pertaining to seamen and desertion.

Although tangential to American maritime history, 1799 saw the fall of a colossus of the world's maritime history. The Dutch East India Company, established on March 20, 1602, when the Estates-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia, formerly the world's largest company, became bankrupt, partly due to the rise of competitive free trade.

The 19th century

During the wars with France (1793 to 1815) the Royal Navy aggressively reclaimed British deserters on board ships of other nations, both by halting and searching merchant ships, and in many cases, by searching American port cities. The Royal Navy did not recognize naturalized American citizenship, treating anyone born a British subject as "British" — as a result, the Royal Navy impressed over 6,000 sailors who were claimed as American citizens as well as British subjects. This was one of the major factors leading to the War of 1812 in North America.

Commercial

As a result of rising tensions with Great Britain, a number of laws collectively known as the Embargo Act of 1807 were enacted. Britain and France were at war; the U.S. was neutral and trading with both sides. Both sides tried to hinder American trade with the other. Jefferson's goal was to use economic warfare to secure American rights, instead of military warfare. Initially, these acts sought to punish Great Britain for its violation of American rights on the high seas; among these was the impressment of those sailors off American ships, sailors who claimed to be American citizens but not in the opinion or to the satisfaction of the Royal Navy, ever on the outlook for deserters. The later Embargo Acts, particularly those of 1807–1808 period, were passed in an attempt to stop Americans, and American communities, that sought to, or were merely suspected of possibility wanting to, defy the embargo. These Acts were ultimately repealed at the end of Jefferson's second, and last, term. A modified version of these Acts would return for a brief time in 1813 under the presidential administration of Jefferson's successor, James Madison.[10]

The African slave trade became illegal on January 1, 1808.[11]

By 1807 the tonnage registered in the United States engaged in foreign trade had increased to 848,307.[8]

The War of 1812

The United States declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812, for a combination of reasons – outrage at the impressment (seizure) of thousands of American sailors, frustration at British restrictions on neutral trade while Britain warred with France, and anger at British military support for hostile tribes in the Ohio-Indiana-Michigan area. After war was declared Britain offered to withdraw the trade restrictions, but it was too late for the American "War Hawks", who turned the conflict into what they called a "second war for independence." Part of the American strategy was deploying several hundred privateers to attack British merchant ships, which hurt British commercial interests, especially in the West Indies.

Clipper ships

In the

Clippers were built for seasonal trades such as tea, where an early cargo was more valuable, or for passenger routes. The small, fast ships were ideally suited to low-volume, high-profit goods, such as spices, tea, people, and mail. The values could be spectacular. The Challenger returned from Shanghai with "the most valuable cargo of tea and silk ever to be laden in one bottom." The competition among the clippers was public and fierce, with their times recorded in the newspapers. The ships had low expected lifetimes and rarely outlasted two decades of use before they were broken up for salvage. Given their speed and maneuverability, clippers frequently mounted cannon or carronade and were often employed as pirate vessels, privateers, smuggling vessels, and in interdiction service.

1815–1830

During the 18th century, ships carrying cargo, passengers and mail between Europe and America would sail only when they were full, but in the early 19th century, as trade with America became more common, schedule regularity became a valuable service. Starting in 1818, ships of the

Because of the influence of whaling and several local droughts, there was substantial migration from Cape Verde to America, most notably to New Bedford, Massachusetts. This migration built strong ties between the two locations, and a strong packet trade between New England and Cape Verde developed during the early to mid-19th century. The Erie Canal was started in 1817 and finished in 1825, encouraging inland trade and strengthening the position of the port of New York.[12]

Although the amount of tonnage registered in foreign trade did not equal that of the years 1815-17 or the figures of the next two decades, the proportion of American carriage in the foreign trade reached 92.5 percent in 1826, a larger percentage than has been attained before or since. Not only were we carrying practically all of our own goods, but the reputation of Yankee ship builders for turning out models which surpassed in speed, strength, and durability any vessels to be found, brought about the sale between 1815 and 1840 of 540,000 tons of shipping to foreigners. Not withstanding higher wages, it cost less to run an American vessel, for a smaller crew was carried. Of the world's total whaling fleet in 1842, it was estimated that of 882 ships 652 were American vessels.[13]

The 1830s

In 1832, Secretary of the Treasury Louis McLane ordered in writing for revenue cutters to conduct winter cruises to assist mariners in need, and Congress made the practice an official part of regulations in 1837. This was the beginning of the lifesaving mission that the later U.S. Coast Guard would be best known for worldwide. The side-wheel paddle steamer SS Great Western was the first purpose-built steamship to initiate regularly scheduled trans-Atlantic crossings, starting in 1838.

The record times of these steam ships (the Atlantic crossing to New York in thirteen and a half days) proved that steamers could make the trip in shorter time than the fastest sailing packet. The British government was farsighted enough to realize that the motive power of the immediate future was steam, and in 1839 heavily subsidized the

The 1840s

The first regular steamship service from the west to the east coast of the

The years leading up to the Civil War were characterized by extremely rapid production in ship building. The 538,136 tons registered in foreign trade in 1831 had increased to 1,047,454 in 1847 and to 2,496,894 in 1862, a figure which represented the culmination of our shipbuilding tonnage until surpassed in WW I. From 1848 to 1858 ship building had been maintained at an average of 400,000 tons a year. This construction was caused by two conditions, the development of the clipper ship after 1845 and the increased demand for shipping.

Designed for speed, the clipper was built on sharp lines and carried a maximum of canvas and was the culmination of the intense rivalry between steam and canvas. It was intended primarily for long voyages, and was used especially for the California and Far Eastern trade. Given a fair breeze, a clipper ship could outdistance a steamship. It was not uncommon for a clipper to sail over 300 miles a day; the Flying Cloud (clipper) on a ninety-day run to San Francisco made 374 miles in one day. The Comet (clipper), on an eighty-day voyage from San Francisco to New York averaged 210 miles a day. It appeared that the American ship builder, before he relinquished his supremacy, was intent upon demonstrating to what heights of efficiency and speed a sailing ship could attain.[16]

The increased demand for shipping was the result of several factors. The discovery in 1848 of gold in California was a major cause along with the wars between Great Britain and China in 1840–42 and 1856–60 threw a part of the China trade into American hands. The revolutionary outbreaks of 1848 interrupted European trade, with a resultant benefit to Americans, while the Crimean War, which occupied many European boats in transporting troops and supplies, gave new openings to American ships. In addition the natural growth in population, wealth, and production necessitated increased shipping.[17]

The volume of mail between the United States and Europe increased substantially during this period, and the capacity of the sailboat to deliver this mail efficiently and within a reasonable time was uncertain. Following the precedent established by England and other maritime nations, the federal government began its aid to ocean shipping with the overseas mail service. On March 3, 1845, Congress authorized the Postmaster General to invite bids on contracts to carry mail between the United States and abroad. Regular subsidized service between New York and Bremen, Havre, Liverpool and Panama was established under the Act of 1845. Subsidy payments averaged between $19,250 and $35,000 per round trip, and aggregated government expenditures to 1858 amounted to $14,400,000.[18]

This development led to the formation of the U.S. Mail Steamship Company and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company.

The 1850s

Almost as revolutionary as the gradual substitution of steam for sailing vessels was the very gradual substitution of iron and later steel ships for those of wood. With an abundance of coal and iron close to the sea, with skilled mechanics and cheap labor, Great Britain forged ahead from the start. Already by 1853 one-fourth of the tonnage built in Great Britain were steamships and more than one-fourth were built of iron. In the same year 22 percent of American tonnage was constructed for steamships, but scarcely any iron ships were built here. The Yankee ship builder, overconfident in the recognized superiority of his inimitable clipper ship, was blinded to the fact that the future of the sea was for the nation which could build the cheapest and the best iron steamships.

There was a decidedly unhealthy element to this remarkable activity in ship building. In the first place the demand from Europe because of the Crimean War was abnormal; between 1854 and 1859 the European nations were buying 50,000 tons of shipping as against 10,000 tons in normal years. Unfortunately, this increase in the building of sailing ships came at a time when their days were numbered, for between 1850 and 1860 the share of ocean freight carried by steamers increased from 14 to 28 percent. When the abnormal demand for sailing ships should let up, as it did in 1858, it meant that shipyards built and equipped for the production of wooden ships and shipwrights trained for a type no longer wanted would be idle, while foreign shipyards already engaged in the building of the iron steamship would be in a decidedly superior position. The panic of 1857 precipitated the crash. In 1858 ship building, which had been maintained for the preceding years at an average of 400,000 tons a year dropped to 244,000 and in 1859 to 156,000. At that time the combined imports and exports carried in American bottoms was steadily declining, only 65.2 percent being carried in 1861 as against 92.5 percent in 1826. Another factor in the decline of American ship building was a fundamental economic change in progress throughout the United States. Capital was finding new and more profitable fields for investment. Manufacturing, which grew rapidly after the War of 1812, absorbed some of it; while considerable amounts were drawn into such internal improvements as canals and railways. Between 1820 and 1838 the states contracted debts of over $110,000,000 for the building of roads, canals, and railroads; from 1830 to 1860 over 30,000 miles of railroad were built, most of the capital coming from private investors. The minds of the venturous and ambitious turned from the sea to the unexploited West, and capital turned from ship building to the development of natural resources.[19]

In 1852, the lighthouse board established and published first

Decline in the use of clippers started with the economic slump following the Panic of 1857 and continued with the gradual introduction of the steamship. Although clippers could be much faster than the early steamships, clippers were ultimately dependent on the vagaries of the wind, while steamers could reliably keep to a schedule. The steam clipper was developed around this time, and had auxiliary steam engines which could be used in the absence of wind. An example of this type was the Royal Charter, built in 1857 and wrecked on the coast of Anglesey in 1859.

In 1859, the "

The 1860s

The final blow to clipper ships came in the form of the Suez Canal, opened in 1869, which provided a huge shortcut for steamships between Europe and Asia, but which was difficult for sailing ships to use.

Civil War era

Merchant shipping was a key target in the U.S. Civil War. For example, the CSS Alabama, a Confederate sloop-of-war commissioned on 24 August 1862, spent months capturing and burning ships in the North Atlantic and intercepting grain ships bound for Europe. Other Confederate commerce raiders included the CSS Sumter, CSS Florida, and CSS Shenandoah.

The elements contributing to the decline of the merchant marine were already operative before the Civil War, and the result would undoubtedly have been the same if that conflict had not come. The war, however, accentuated a tendency already existing and dealt a blow from which the merchant marine failed to recover until artificially revived during World War I. In 1861 registered American tonnage in foreign trade amounted to 2,496,894 tons and in 1865 to 1,518,350, while the percent of imports and exports carried in American ships dropped in the same years from 66.2 to 27.7. The decrease of tonnage in these years of some 900,000 tons was chiefly due to two causes. The first of these was the loss sustained from Confederate cruisers such as the Alabama built and fitted out in England contrary to the laws of warfare. The second and most important was the sale during the four years 1862–65 of 751,595 tons of shipping abroad, occasioned by (1) lack of confidence, decline in profits due to continual Confederate captures and high insurance rates, and (2) decline in export business due to the cessation of cotton shipments abroad.[20]

A second round of ocean-mail contracts was authorized by Congress on May 28, 1864. Pursuant to the provisions of this Act, the United States and Brazil entered into a ten-year contract for monthly voyages between the United States and South America. Of the $250,000 annual subsidy requirement, the United States contributed $150,000 and Brazil $100,000. Subsequent subsidies to various individual American flag lines amounted to approximately $6,500,000 between 1864 and 1877.[18] Efforts by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company to increase its subsidies and the political scandals that grew out of these efforts, caused the Government to abrogate all subsidies to the Lines. Little more was done by the Government until the passage of the Ocean Mail Act in 1891.[21]

1866–1870

First West Coast attempt at unionizing merchant seamen with the "Seamen's Friendly Union and Protective Society." The union quickly dissolves.[5]

The Civil War dealt the merchant marine a blow from which it never recovered except for the assistance of government intervention in World War I and later. Destruction by Confederate privateers and large sales abroad decreased the amount of tonnage. Delay in adopting iron steam-driven ships gave British builders an advantage which they continued to hold. But more important than all else was the fact that more profitable investments in internal transportation and the exploration of raw materials in the great industrial age which dawned after the war drew capital away from the sea. Lack of government interest helped complete the downfall of American shipping.

The five years following the Civil War showed a slight revival but the forces tending to a decline continued operative. American shipping in foreign trade and the fisheries, which amounted to 2,642,628 tons in 1870, had dropped to 826,694 tons in 1900. In 1860 the percentage of imports and exports carried in American ships was 66.5, but this dropped in 1870 to 35.6, in 1880 to 13, in 1890 to 9.4, in 1900 to 7.1.[22]

The 1870s

By 1870, a number of inventions, such as the

The 1880s

In 1880, passenger steamship

The 1890s

In 1891, a maritime school now known as The Massachusetts Maritime Academy opened up in Buzzards Bay Massachusetts.

The Ocean Mail Act of 1891 provided for mail-subsidy payments to various classes of steamships and inaugurated a trade-route system which remained basically unchanged up to the present day. Under the Act's directive to "subserve and promote the postal and commercial interest of the United States," the Postmaster General invited bids under which contracts were subsequently awarded on routes which varied in number from four to nine. The Act remained in effect until 1923, and total subsidy in the form of mail payments totaled $29,630,000.[18]

The early 20th century

In 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or "the Wobblies") was founded, representing mainly unskilled workers. "The Wobblies," a force in American labor only for about 15 years, were largely routed by the Palmer Raids after World War I. In 1908, Andrew Furuseth became president of the International Seamen's Union and served in that office until 1938.[28]

The 1910s

During this period, Andrew Furuseth successfully pushed for legislative reforms that eventually became the Seamen's Act.[28] During World War I there was a shipping boom and ISU's membership included more than 115,000 dues-paying members.[29] However, when the boom ended, the ISU's membership shrunk to 50,000.[29]

. In 1915, the Seamen's Act of 1915

- abolished the practice of imprisonment for seamen who deserted their ship

- reduced the penalties for disobedience

- regulated a seaman's working hours both at sea and in port

- established a minimum quality for ship's food

- regulated the payment of seamen's wages

- required specific levels of safety, particularly the provision of lifeboats

- required a minimum percentage of the seamen aboard a vessel to be qualified Able Seamen

- required a minimum of 75 percent of the seamen aboard a vessel to understand the language spoken by the officers

Laws like the Seaman's Act put U.S.-flagged vessels at an economic disadvantage against countries lacking such safeguards.

President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the act to create the United States Coast Guard on January 28, 1915. This Act effectively combined the Revenue Cutter Service with the Lifesaving Service and formed the new United States Coast Guard. Gradually the Coast Guard would grow to incorporate the United States Lighthouse Service in 1939 and the Navigation and Steamboat Inspection Service in 1942.

World War I

Shipbuilding became a major wartime industry, focused on merchant ships and tankers.[33] Merchant ships were often sunk until the convoy system was adopted using British and Canadian naval escorts, Convoys were slow but were effective in stopping U-boat attacks.[34] The troops were shipped over on fast passenger liners that could easily outrun submarines.[35]

In the First World War, Britain, as an island nation, was heavily dependent on foreign trade and imported resources. Germany found that their submarines, or

By 1915, Germany was attempting to use submarines to maintain a naval blockade of Britain by sinking cargo ships, including many passenger vessels. Submarines, however, depending on stealth and incapable of withstanding a direct attack by a surface ship (possibly a

Over time, the use of defended convoys of merchant ships allowed the Allies to maintain shipping across the Atlantic, in spite of heavy loss. The Royal Navy had conducted convoys in the Napoleonic Wars and they had been used effectively to protect troopships in the current war, but the idea of using them to protect merchant shipping had been debated for several years. Nobody was sure if convoys were Britain's salvation or ruin. Consolidating merchant ships into convoys might just provide German U-boats with a target-rich environment, and packing ships together might lead to collisions and other accidents. It was potentially a logistical nightmare as well, and allied officers judged it too much so.

With the ability to replace losses, the dilemma of using convoys was not as painful. After experiments through the early months of 1917 that proved successful, the first formal convoys were organized in late May. By the autumn the convoy system had become very well organized, and losses for ships in convoy fell drastically, with 2% losses for ships in convoy compared to 10% losses for ships traveling on their own. The convoy loss rate dropped to 1% in October. However, convoy was not mandatory, and monthly loss rates did not fall below their 1916 levels until August 1918.

The need for administering the merchant marine during wartime was demonstrated during the First World War.[37] Commerce warfare, carried on by submarines and merchant raiders, had a disastrous effect on the Allied merchant fleet.[38] With the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, U-boats sank ships faster than replacements could be built.[38]

1919–1930

Another of ISU's successes was the strike of 1919, which resulted in wages that were "an all-time high for deep sea sailors in peacetime."[29] However, ISU had its shortcomings and failures, too. After a round of failed contract negotiations, ISU issued an all-ports strike on May 1, 1921. The strike lasted only two months and failed, with resulting wage cuts of 25 percent.[29] The ISU, as with all AFL unions, was criticized as being too conservative. For example, in 1923 the Industrial Workers of the World publication The Marine Worker referred to the ISU's "pie-cards" (paid officials) as "grafters and pimps."[39] In 1929, the California Maritime Academy established.[9]

1930–1941

In 1933,

West Coast sailors deserted ships in support of the

The merchant marine in the United States was in a state of decline in the mid-1930s.

The commission realized that a trained merchant marine work force was vital to the national interest. At the request of Congress, the chairman of the Maritime Commission, VADM

Joseph P. Kennedy named head of

NMU formation

In 1936, an ISU

Believing it was time to abandon the conservative ISU, Curran began recruiting members for a new rival union. The level of organizing was so intense that hundreds of ships delayed sailing as seamen listened to organizers and signed union cards.[47] The ISU's official publication, The Seamen's Journal, suggested Curran's "sudden disenchantment" with the ISU was odd, since he'd only been a "member of the union for one year during his seafaring career."[29]

In May 1937, Curran and other leaders of his Seamen's Defense Committee reconstituted the group as the National Maritime Union. Holding its first convention in July, approximately 30,000 seamen switched their membership from the ISU to the NMU and Curran was elected president of the new organization.[42][43][45] Within a year, the NMU had more than 50,000 members and most American shippers were under contract.[45][47]

SIU formation

In August 1937,

The 1940s

World War II

As with the other military services, the entry of the United States into the Second World War necessitated the immediate growth of the merchant marine and the Coast Guard.[38] The Maritime Commission spawned the War Shipping Administration in early February 1942. This new agency received a number of functions considered vital to the war effort, including maritime training. Several weeks after the creation of the new agency, however, the Maritime Service was transferred again to the Coast Guard.[38] The transfer allowed the War Shipping Administration to concentrate on organizing American merchant shipping, building new ships, and carrying cargoes where they were needed most.[38]

The United States intended to meet this crisis with large numbers of mass-produced freighters and transports.[38] When World War II loomed, the Maritime Commission began a crash shipbuilding program utilizing every available resource.[38] The experienced shipyards built complicated vessels, such as warships.[38] New shipyards, which opened almost overnight around the country, generally built less sophisticated ships such as the emergency construction "Liberty ships".[38] By 1945 the shipyards had completed more than 2,700 "Liberty" ships and hundreds of "Victory ships", tankers and transports.[38]

All of these new ships needed trained officers and crews to operate them.

Training ships crewed by the Coast Guard included the Maritime Commission steamships American Seaman,

Licensed and unlicensed merchant marine personnel enrolled in the service.[38] The ranks, grades, and ratings for the Maritime Service were based on those of the Coast Guard.[38] Training for experienced personnel lasted three months; while inexperienced personnel trained for six months.[38] Pay was based on the person's highest certified position in merchant service.[38] New students received cadet wages.[38] American citizens at least 19 years old, with one year of service on American merchant vessels of more than 500 gross tons, were eligible for enrollment.[38] Coast Guard training of merchant mariners was vital to winning the war.[38] Thousands of the sailors who crewed the new American merchant fleet trained under the watchful eyes of the Coast Guard.[38]

The Coast Guard only continued the administration of the Maritime Service for ten months after the United States entered the war.[38] Merchant marine training and most aspects of merchant marine activity transferred to the newly created War Shipping Administration on September 1, 1942.[38] The transfer allowed the Coast Guard to take a more active role in the war and concentrated government administration of the merchant marine in one agency.[38] However, just as the transfer removed the merchant marine training role from the Coast Guard, the service assumed the role of licensing seamen and inspecting merchant vessels.[38]

The

Several ships were torpedoed within sight of East Coast cities such as New York and Boston; indeed, some civilians sat on beaches and watched battles between U.S. and German ships.[citation needed]

Once convoys and air cover were introduced, sinking numbers were reduced and the U-boats shifted to attack shipping in the Gulf of Mexico, with 121 losses in June. In one instance, the tanker Virginia was torpedoed in the mouth of the Mississippi River by the German submarine U-507 on May 12, 1942, killing 26 crewmen. There were 14 survivors. Again, when defensive measures were introduced, ship sinkings decreased and U-boat sinkings increased.

The cumulative effect of this campaign was severe; a quarter of all wartime sinkings—3.1 million tons. There were several reasons for this. The naval commander, Admiral

In 2017, Sadie O. Horton, who spent World War II working aboard a coastwise U.S. Merchant Marine barge, posthumously received official veteran's status for her wartime service, becoming the first recorded female Merchant Marine veteran of World War II.[49]

Wartime issues

During the Second World War, the merchant service sailed and took orders from naval officers. Some were uniformed, and some were trained to use a gun. However, they were formally considered volunteers and not members of the military. Walter Winchell, the famous newspaper columnist and radio commentator, and columnist Westbrook Pegler both described the National Maritime Union and the merchant seamen generally as draft dodgers, criminals, riffraff, Communists, and other derogatory names.

It came to a head in the middle of the war with the writing of a column in the

What was ignored, say the

The biggest supporter of the merchant sailors was President

Roosevelt, while the war was under way, proclaimed "Mariners have written one of its most brilliant chapters. They have delivered the goods when and where needed in every theater of operations and across every ocean in the biggest, the most difficult and dangerous job ever undertaken. As time goes on, there will be greater public understanding of our merchant's fleet record during this war."

But it wasn't to be, for with Roosevelt's death in 1945, the Merchant Marine lost its staunchest supporter and any chance to share in the accolades afforded others who served. The War Department, the same government branch that recruited them, opposed the Seaman's Bill of Rights in 1947 (see below) and managed to kill the legislation in congressional committee, effectively ending any chance for seamen to reap the thanks of a nation. For 43 years, the U.S. government denied them benefits ranging from housing to health care until Congress awarded them veterans' status in 1988, too late for 125,000 mariners, roughly half of those who had served.

Today there are shrine and memorial reminders of mariners' heroism such as The

Since the

In the late 1940s, the Liberian open registry was formed as the brainchild of

On 11 March 1949, Greek shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos registered the first ship under the Liberian flag of convenience, the World Peace. When Stettinius died in 1950, ownership of the registry passed to the International Bank of Washington, led by General George Olmsted.[52] Within 18 years, Liberia grew to surpass the United Kingdom as the world's largest register.[52]

The 1950s

The

Korean War

During the Korean War there were few severe sealift problems other than the need to re-mobilize forces following post–World War II demobilization. About 700 ships were activated from the NDRF for services to the Far East. In addition, a worldwide tonnage shortfall between 1951 and 1953 required the reactivation of over 600 ships to lift coal to Northern Europe and grain to India during the first years of the Cold War. The commercial merchant marine formed the backbone of the bridge of ships across the Pacific. From just six ships under charter when the war began, this total peaked at 255. According to the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS), 85 percent of the dry cargo requirements during the Korean War were met through commercial vessels – only five percent were shipped by air. More than $475 million, or 75 percent of the MSTS operating budget for calendar year 1952, was paid directly to commercial shipping interests. In addition to the ships assigned directly to MSTS, 130 laid-up Victory ships in the NDRF were broken out by the Maritime Administration and assigned under time-charters to private shipping firms for charter to MSTS.

Ships of the MSTS not only provided supplies but also served as naval auxiliaries. When the

Merchant ships played an important role in the evacuation of

Privately owned American merchant ships helped deploy thousands of U.S. troops and their equipment, bringing high praise from the commander of U.S. Naval Forces in the Far East, Admiral Charles T. Joy. In congratulating Navy Captain A.F. Junker, Commander of the Military Sea Transportation Service for the western Pacific, Admiral Joy noted that the success of the Korean campaign was dependent on the Merchant Marine. He said, "The Merchant Mariners in your command performed silently, but their accomplishments speak loudly. Such teammates are comforting to work with."

Government owned merchant vessels from the National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) have supported emergency shipping requirements in seven wars and crises. During the Korean War, 540 vessels were activated to support military forces. From 1955 through 1964, another 600 ships were used to store grain for the Department of Agriculture. Another tonnage shortfall following the Suez Canal closing in 1956 caused 223 cargo ship and 29 tanker activations from the NDRF.[54]

1953–1960

In 1953 at the Sixth Biennial Convention of the SIUNA the BME gained autonomy, which would allow it to adopt its first constitution and elect officers for the first time.[55] The first constitution was drafted by Edward Reisman, Rudolph Wunsch, James Wilde, Everett Landers, Peter Geipi, and William Lovvorn,[56] who "wanted to craft a document that would provide for free and fair elections, set the terms of office for official positions, specify the duties of union officials, provide for charges, trials, and appeals, permit rank and file membership inspection of the union's financial records, and permit amendments by rank and file vote."[56] The constitution, allowing for the election of a president, two vice-presidents, and a secretary-treasurer, was adopted with 96 percent of the membership voting to adopt it.[56] Wilbur Dickey was elected first president on December 15, 1953. In September 1954, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) recognized the fledgling union, by granting it "exclusive jurisdiction within the federation over 'licensed engine room personnel on self-propelled vessels.'"[57]

The BME Welfare Plan was growing at an impressive rate under the care of Director of Welfare and Special Services Ray McKay. In August 1954, he reported its assets to be in excess of $100,000.[58] The plan offered a number of progressive benefits, such as full surgery coverage for members and their families, and full coverage for seeing a physician. In February 1955, the union began pursuing the "first pension plan ever for U.S. merchant marine officers," which was well underway by November 1955.[58]

In 1955, Joseph Curran was named a vice-president of the

The late 20th century

1960s

In 1960, after an internal reorganization of MEBA, American Maritime Officers became known as "District 2 MEBA."

Vietnam War

During the

The 1970s

In 1970, the Merchant Marine Act authorized a subsidized shipbuilding program.

The 1980s

In 1981, the

The 1990s

In 1992, while functioning as an autonomous union within MEBA, "District 2" reverted to its original name of "American Maritime Officers."[53] In 1993, Raymond T. McKay died, his son Michael McKay replaced him as American Maritime Officers president. AMO finally withdrew from MEBA in 1994[53] and resultingly lost its AFL-CIO affiliation[62] This was restored after approximately a decade, on March 12, 2004, when Michael Sacco presented AMO with a charter from SIUNA.[62]

Two RRF tankers, two RO/RO ships and a troop transport ship were needed in

The 2000s

On October 22, 2001, the Merchant Marine Act of 2001 was enacted, providing for the construction of 300 ships in a span of ten years.[63] In 2003, 40 RRF ships were used in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. This RRF contribution was significant and included sealifting equipment and supplies into the theatre of combat operations, which included combat support equipment for the Army, Navy Combat Logistics Force, and USMC Aviation Support equipment. By the beginning of May 2005, RRF cumulative support included 85 ship activations that logged almost 12,000 ship operating days, moving almost 25% of the equipment needed to support the U.S. Armed Forces liberation of Iraq.[54] MSC is also involved in the current Iraq War, having delivered 61 million square feet (5.7 km2) of cargo and 1.1 billion US gallons (4,200,000 m3) of fuel by the end of the first year alone. Merchant mariners are being recognized for their contributions in Iraq. For example, in late 2003, Vice Adm. David Brewer III, commander of Military Sealift Command, awarded the officers and crewmembers of MV Capt. Steven L. Bennett the Merchant Marine Expeditionary Medal.[64]

On January 8, 2007, Tom Bethel was appointed by the AMO national executive committee to fulfil the term of former president Michael McKay.[65] The RRF was called upon to provide humanitarian assistance to gulf coast areas following Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita landfalls in August and September, respectively, of 2005. The Federal Emergency Management Agency requested a total of eight vessels to support relief efforts. Messing and berthing was provided for refinery workers, oils spill response teams, longshoremen. One of the vessels provided electrical power.[54]

In 2020, Congress passed the Merchant Mariners of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act to recognize the merchant mariners for their courage and contributions during the war. During World War II, nearly 250,000 civilian merchant mariners served as part of the U.S. military and delivered supplies and armed forces personnel by ship to foreign countries engulfed in the war. Between 1939 and 1945, 9,521 merchant mariners died – a higher proportion than those killed than in any military branch, according to the National WWII Museum.[66]

"President Franklin D. Roosevelt called their mission the most difficult and dangerous transportation job ever undertaken," House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said at the ceremony, which was held at the U.S. Capitol and attended by congressional and military leaders.[66]

The Congressional Gold Medal will be displayed at the

Two of the World War II mariners – Charles Mills, 101, of Baltimore, Maryland, and Dave Yoho, 94, of Vienna, Virginia – attended the ceremony at the U.S. Capitol.[66]

See also

- Awards and decorations of the United States Merchant Marine

- Maritime history

- Jones Act

- Liberty ship

- Navy Reserve Merchant Marine Badge

- Sailortown (dockland)

- History of slavery in the United States

- United States Maritime Service

- United States Merchant Marine

- United States Merchant Marine Academy

Notes

- ^ Harold Underwood Faulkner, American Economic History, Harper & Brothers Publishers, Copyright 1938, p. 672

- ^ Hough, Benjamin Olney (1916). Ocean Traffic and Trade. LaSalle Extension University.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783–1860 (1921) excerpt and text search

- ^ a b c d See First Barbary War.

- ^ a b c "The Lookout of the Labor Movement" (PDF). Sailors Union of the Pacific. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ a b Harold Underwood Faulkner, American Economic History, Harper & Brothers, 1938, p. 182

- ISBN 0-89453-153-0p. 113

- ^ a b Hough, Benjamin Olney (1916). Ocean Traffic and Trade. LaSalle Extension University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "American Merchant Marine Timeline, 1789–2005". Barnard's Electronic Archive and Teaching Library. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ See Embargo Act of 1807.

- ^ See Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6th ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/Bartleby.com.

1808

. - ^ See Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6th ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/Bartleby.com.

1825

. - ^ Faulkner, pp. 280–281

- ^ p. 332 https://books.google.com/books?id=rzIuAAAAYAAJ

- ^ Faulkner, pp. 282–283

- ^ Faulkner, p. 283

- ^ Faulkner, p. 284

- ^ a b c http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1916&context=flr [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Faulkner, pp. 284–285

- ^ Faulkland, pp. 285–286

- ^ p. 336 https://books.google.com/books?id=rzIuAAAAYAAJ

- ^ Faulkner, pp. 672–673

- ^ Jehl, Francis Menlo Park reminiscences : written in Edison's restored Menlo Park laboratory, Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Whitefish, Mass, Kessinger Publishing, 2002, p. 564

- ^ Dalton, Anthony A long, dangerous coastline : shipwreck tales from Alaska to California Heritage House Publishing Company, 2011, 128 pp.

- ^ Swann, p. 242.

- ^ "Lighting A Revolution: 19th Century Promotion". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ "Chapter I: The Lookout of the Labor Movement" (PDF). SUP History. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Andrew Furuseth". Norwegian American Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "SIU & Maritime History". seafarers.org. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ a b "Glossary". The Samuel Gompers Papers. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ a b DeSombre 2006, p. 75.

- ^ a b DeSombre 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Beamish and March (1919). America's Part in the World War. John C. Winston Company. pp. 359–66.

- ^ Brian Tennyson, and Roger Sarty. "Sydney, Nova Scotia and the U-boat War, 1918." Canadian Military History 7.1 (2012): 4+ online

- ^ Holger H. Herwig, and David F. David. "The Failure of Imperial Germany's Undersea Offensive Against World Shipping, February 1917–October 1918." Historian (1971) 33#4 pp: 611–636.

- ^ "History Associates Cofounder Rodney Carlisle Authors New Book on World War I", History Associates (www.historyassociates.com), retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ^ "Training Merchant Marines For War: The Role of the United States Coast Guard", United States Coast Guard U.S. Department of Homeland Security (www.uscg.mil), retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar United States Coast Guard (January 2001). "Training Merchant Mariners for War: The Role of the United States Coast Guard". Retrieved May 26, 2007. [dead link]

- ^ "Wobbly Protest". Time magazine. July 23, 1923. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ "Harry Bridges: Rank-and-File Leader". The Nation. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ a b "Chapter VIII: Twilight of Freedom" (PDF). Sailor's Union of the Pacific History. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2007. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Barbanel, "Joseph Curran, 75, Founder of National Maritime Union," The New York Times, August 15, 1981.

- ^ a b c Kempton, Part of Our Time: Some Monuments and Ruins of the Thirties, 1998 (1955).

- ^ "Retired Union Boss Joseph Curran Dies," Associated Press, August 14, 1981.

- ^ a b c d Schwartz, Brotherhood of the Sea: The Sailors' Union of the Pacific, 1885–1985, 1986.

- ^ "Politics and Pork Chops," Time, June 17, 1946.

- ^ a b "C.I.O. Goes to Sea," Time, July 19, 1937.

- ^ "SIU & Maritime History". SIU History. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ "Horton first woman to earn veteran status as WWII merchant mariner". Daily Advance. 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Flag Archived July 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d DeSombre 2006, p. 74.

- ^ a b Pike, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "The Beginning". AMO Past and Present. Archived from the original on April 26, 2007. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The National Defense Reserve Fleet" (PDF). United States Maritime Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ "1953: Union Defies Skeptics With Democratic Procedures, Organizing, Contracts". AMO History. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c "SIUNA Grants BME Autonomy". AMO History. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ "AFL Recognizes BME As A Stable Force In Maritime Labor". AMO History. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "First-Ever Ship Officers' Pension Plan Was Among BME's Benefit Triumphs". AMO History. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ "The Early Years: New Union Elects First Administration". AMO History. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ "'57: BME, MEBA Agree On Merger". AMO History. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ National Maritime Day, 2002

- ^ a b "Charter from SIUNA means new security, opportunity for AMO". American Maritime Officer. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6th ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/Bartleby.com.

Merchant Marine Act of 2001

- ^ "AMO members serve in military operations, exercises". American Maritime Officer magazine. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ "Bethel pledges to work with membership and new officials to "right the AMO ship"" (PDF). American Maritime Officer. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2007. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Cronk, TerryiMoon (May 19, 2022). "WWII Merchant Mariners Receive Congressional Gold Medal". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

References

- De La Pedraja, René. Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Merchant Marine and Shipping Industry: Since the Introduction of Steam (1994) online

- DeSombre, Elizabeth (2006). Flagging Standards : Globalization and Environmental, Safety, and Labor Regulations at Sea. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54190-9. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- Gibson, E. Kay (2006). Brutality on Trial: Hellfire Pedersen, Fighting Hansen, And the Seaman's Act of 1915. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 225. ISBN 0-8130-2991-0. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- Herbert, Brian. "review of The Forgotten Heroes: The Heroic Story of the United States Merchant Marine". Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- Pike, John (2008). "History of Liberian Ship Registry". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- Pro, Joanna (May 30, 2004). "Unsung Heroes of World War II: Seamen of the Merchant Marine still struggle for recognition". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- "The Merchant Marines in the Korean War". United States Army. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- Thomas, Guy. "A Maritime Traffic-Tracking System: Cornerstone of Maritime Homeland Defense". Naval War College Regiew. Archived from the original on May 17, 2006. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- Thomas, Michelle. "Lost at Sea and Lost at Home: The Predicament of Seafaring Families" (PDF). Seafarers International Research Centre. Cardiff University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

External links

General information

- Sea History at the National Maritime Historical Society

- American Merchant Marine at War

- United States Merchant Marine in history

- Casualty statistics World War II

- Recipients of Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal

- Seafarers International Union – War's Forgotten Heroes

- Heave Ho – The United States Merchant Marine Anthem (lyrics only)

- Fairplay The International Shipping Weekly

- The Nautical Institute

- A Maritime Tracking System: Cornerstone of Maritime Homeland Defense