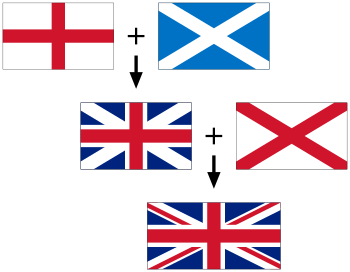

Formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2012) |

The formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland has involved personal and political union across Great Britain and the wider British Isles. The United Kingdom is the most recent of a number of sovereign states that have been established in Great Britain at different periods in history, in different combinations and under a variety of polities. Historian Norman Davies has counted sixteen different states over the past 2,000 years.[1]

By the start of the 16th century, the number of states in Great Britain had been reduced to two: the

The Acts of Union 1800 united the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland, which had been gradually brought under English control between 1541 and 1691, to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. Independence for the Irish Free State in 1922 followed the partition of the island of Ireland two years previously, with six of the nine counties of the province of Ulster remaining within the UK, which then changed to the current name in 1927 of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

In the 20th century, the rise of Welsh and Scottish nationalism and resolution of the Troubles in Ireland resulted in the establishment of devolved parliaments or assemblies for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Background

England's conquest of Wales

Through internal struggles and dynastic marriage alliances, the Welsh became more united until

In 1282, following another rebellion,

Initially, the Crown had only indirect control over much of Wales because the

There was no major uprising except that led by Owain Glyndŵr a century later, against Henry IV of England. In 1404 Glyndŵr was crowned Prince of Wales in the presence of emissaries from France, Spain, and Scotland; he went on to hold parliamentary assemblies at several Welsh towns, including Machynlleth. The rebellion was ultimately to founder, however. Glyndŵr went into hiding in 1412, and peace was more or less restored in Wales by 1415.

The power of the Marcher lords was ended in 1535, when the political and administrative union of England and Wales was completed. The

English Conquest of Ireland

By the 12th century,

With the authority of the papal bull Henry landed with a large fleet in 1171 and claimed sovereignty over the island. A peace treaty followed in 1175, with the Irish High King keeping lands outside Leinster, which had passed to Henry on the expected death of both Diarmait and de Clare. When the High King lost his authority Henry awarded his Irish territories to his younger son

There was a resurgence of Gaelic power as rebellious attacks stretched Norman resources. Politics and events in Gaelic Ireland also served to draw the settlers deeper into the orbit of the Irish. When the Black Death arrived in Ireland in 1348 it hit the English and Norman inhabitants who lived in towns and villages far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the countryside again. The English-controlled area shrunk back to the Pale, a fortified area around Dublin.

Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords adopted the Irish language and customs. Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and generally stayed Catholic after the

In 1532,

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England. In 1541, he upgraded Ireland from a lordship to a full kingdom. Henry was proclaimed

From the mid-16th and into the early 17th century, Crown governments carried out a policy of

Personal Union: Union of the Crowns

In August 1503

James had the idealistic ambition of building on the personal union of the crowns of Scotland and England so as to establish a permanent Union of the Crowns under one monarch, one parliament, and one law. He insisted that English and Scots should "join and coalesce together in a sincere and perfect union, as two twins bred in one belly, to love one another as no more two but one estate". James's ambitions were greeted with very little enthusiasm, as one by one members of parliament rushed to defend the ancient name and realm of England. All sorts of legal objections were raised: all laws would have to be renewed and all treaties renegotiated. For James, whose experience of parliaments was limited to the stage-managed and semi-feudal Scottish variety, the self-assurance – and obduracy – of the English version, which had long experience of upsetting monarchs, was an obvious shock. The Scots were no more enthusiastic than the English because they feared being reduced to the status of Wales or Ireland. In October 1604, James assumed the title "King of Great Britain" by proclamation rather than statute, although Sir Francis Bacon told him he could not use the title in "any legal proceeding, instrument or assurance". The two realms continued to maintain separate parliaments. The Union of the Crowns had begun a process that would lead to the eventual unification of the two kingdoms. However, in the ensuing hundred years, strong religious and political differences continued to divide the kingdoms, and common royalty could not prevent occasions of internecine warfare.

James did not create a

Ruling over the diverse kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland proved difficult for James and his successor

In 1625, James was succeeded by his son

Alienated by British Protestant domination and frightened by the rhetoric of the English and Scottish Parliaments, a small group of Irish conspirators launched the Irish Rebellion of 1641, ostensibly in support of the "King's Rights". The rising was marked by widespread assaults on the British Protestant communities in Ireland, sometimes culminating in massacres. Rumours spread in England and Scotland that the killings had the King's sanction and that this was a foretaste of what was in store for them if the King's Irish troops landed in Britain. As a result, the English Parliament refused to pay for a royal army to put down the rebellion in Ireland and instead raised its own armed forces. The King did likewise, rallying those Royalists (some of them members of Parliament) who believed that loyalty to the legitimate King was the most important political principle.

The

After the end of the second English Civil War, the victorious Parliamentary forces, now commanded by Oliver Cromwell, invaded Ireland and crushed the Royalist-Confederate alliance there in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. Their alliance with the Scottish Covenanters had also broken down, and the Scots crowned Charles II as king. Cromwell therefore embarked on a conquest of Scotland in 1650–51. By the end of the wars, the Three Kingdoms were a unitary state called the English Commonwealth, ostensibly a republic but having many characteristics of a military dictatorship.

While the Wars of the Three Kingdoms pre-figured many of the changes that would shape modern Britain, in the short term it resolved little. The

Ireland and Scotland were occupied by the New Model Army during the Interregnum. In Ireland, almost all lands belonging to Irish Catholics were confiscated as punishment for the rebellion of 1641; harsh

Under the

When

Formation of the Union

Acts of Union 1707

Deeper political integration was a key policy of

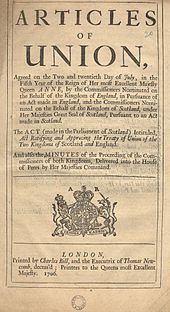

In 1707, the Acts of Union received their

However, certain aspects of the former independent kingdoms remained separate. Examples of Scottish and English institutions that were not merged into the British system include

Acts of Union 1800

After the

The legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland was completed by the Acts of Union 1800 passed by each parliament, uniting the two kingdoms into one, called "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland".[7] The twin Acts were passed in the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland with substantial majorities achieved in Ireland in part (according to contemporary documents) through bribery, namely the awarding of peerages and honours to critics to get their votes.[8]

Under the terms of the union, there was to be but one Parliament of the United Kingdom.[9] Ireland sent four lords spiritual (bishops) and twenty-eight lords temporal to the House of Lords and one hundred members to the House of Commons at Westminster. The lords spiritual were chosen by rotation, and the lords temporal were elected from among the peers of Ireland.

Part of the arrangement as a trade-off for Irish Catholics was to be the granting of

Table of historic merging of territories within the UK

| Date | Statute/Act etc. | Territories included | Name | Notes | Not included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1284 | - | - | - | - | Separate countries in/of England / Ireland / Scotland / Wales |

| 1284 | Statute of Rhuddlan | England & Wales | England | Principality of Wales annexed to the Crown of England | Kingdom of Scotland / Lordship of Ireland since 1171 |

| 1536 | Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 | England & Wales | Kingdom of England | Wales fully incorporated into the Kingdom of England | Kingdom of Scotland / Lordship of Ireland, shortly to become Kingdom of Ireland in Crown of Ireland Act 1542 |

| 1603 | Union of the Crowns | England, Scotland & Wales (under a common king) | Great Britain | James VI and I titled "King of Great Brittaine, France, and Ireland" although he did not actually rule France; Ireland effectively a subject nation | Kingdom of Ireland (Since 1541/42) |

| 1707 | Acts of Union 1707 | England, Scotland & Wales (merging of parliaments) | Kingdom of Great Britain | See Monarchy of Scotland -personal union between the Crown of Scotland and the British Crown becomes a political union |

Kingdom of Ireland |

| 1801 | Acts of Union 1800 | England, Ireland, Scotland & Wales | United Kingdom of Great Britain & Ireland |

Parliament of Ireland approved political union of monarchies of Ireland and Great Britain | - |

| 1921 | Anglo-Irish Treaty | England, Northern Ireland, Scotland & Wales | United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland |

establishment of the Irish Free State | Irish Free State, later Republic of Ireland or Éire (see Names of the Irish state) |

See also Documents relevant to personal and legislative unions of the

The "disuniting" of the United Kingdom

Irish alienation and independence

The 19th century saw the

The 19th century and early 20th century saw the rise of

The Irish Free State was initially a

The "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland" continued in name until 1927 when it was renamed the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" by the

Despite increasing political independence from each other from 1922, and complete political independence since 1949, the union left the two countries intertwined with each other in many respects. Ireland used the

Northern Ireland remains part of the United Kingdom. Since 1922, it has sometimes enjoyed self-government, and at other times has been ruled directly from Westminster. However, even while governing itself, it has always kept its representation in the United Kingdom Parliament, and has formed part of the country which, since 1927, has included "Northern Ireland" in its name.

Devolution

Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Assembly in its current guise was first elected on 25 June 1998 and first met on 1 July 1998. However, it only existed in "shadow" form until 2 December 1999 when full powers were devolved to the Assembly. The Assembly's composition and powers are laid down in the Northern Ireland Act 1998. The Assembly has both legislative powers and responsibility for electing the Northern Ireland Executive.

The Assembly has authority to legislate in a field of competences known as "transferred matters". These matters include any competence not explicitly retained by the Parliament at Westminster. Powers reserved by Westminster are divided into "excepted matters", which it retains indefinitely, and "reserved matters", which may be transferred to the competence of the Northern Ireland Assembly at a future date.

Scotland

A Scottish Parliament was convened by the Scotland Act 1998, following a referendum in 1997, in which the Scottish electorate voted for devolution. The first meeting of the new Parliament took place on 12 May 1999. It has the power to legislate in all areas that are not explicitly reserved to Westminster. The British Parliament retains the ability to amend the terms of reference of the Scottish Parliament, and can extend or reduce the areas in which it can make laws.

Wales

The

In November 2019, the Assembly voted to change its name to Senedd Cymru or the Welsh Parliament, referred simply as the Senedd in both Welsh and English,[13] a name change that took effect from 6 May 2020.[14]

Future

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Prospect of Scottish independence

In 2014, 55% of Scottish voters rejected leaving the UK in an independence referendum. However, after the 2016 European Union membership referendum, in which Scotland, as well as Northern Ireland, voted to remain in the EU while England and Wales voted to leave, there is the prospect of a second Scottish independence referendum. With some polls on support for Scottish independence being in the majority in 2020, however, polls have a margin of error and many do not include 16-17-year-olds like in the 2014 referendum.

Prospect of Welsh independence

Wales voted to leave in the EU referendum. However, historically the support for Welsh independence has predominantly been low, ranging between 10% in 2013 and 24% in 2019. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, however, popular support has risen. One poll in March 2021 showed that, with "don't knows" removed, nearly 40% of Welsh people were in favour of independence.[15]

Prospect of Irish reunification

In 1973, Northern Ireland had a referendum on Irish reunification, though the result was in favour of the United Kingdom and the poll was boycotted by Nationalists. The 1998 Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement referendum was then held to approve the Good Friday Agreement, which among other things, included a clause which states that a border poll on Irish reunification must be held if public opinion is shown to have changed in favour of a United Ireland.

See also

- Constitution of the United Kingdom

- History of the Constitution of the United Kingdom

Notes

- ^

Notwithstanding any other provision of this Constitution, a person born in the island of Ireland, which includes its islands and seas, who does not have, at the time of the birth of that person, at least one parent who is an Irish citizen or entitled to be an Irish citizen is not entitled to Irish citizenship or nationality, unless provided for by law. This section shall not apply to persons born before the date of the enactment of this section

— 27th Amendment to the Constitution of Ireland; Article 9 (Section 2, 1°)

References

- ISBN 0-333-69283-7).

- ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- ISBN 0-19-821732-3

- ISBN 0-300-07209-0)

- ^ Articles of Union with Scotland 1707 Archived 3 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine www.parliament.uk

- ^ Laws in Ireland for the Suppression of Popery Archived 3 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine at University of Minnesota Law School

- ^ Article I, Treaty of Union 1800

- ^ Alan J. Ward, The Irish Constitutional Tradition p.28.

- ^ Article III, Treaty of Union 1800

- Eire's ceasing to be a member of the Commonwealth"

- ^ British National Archives, Catalogue Reference:CAB/129/32 (Memorandum by PM Attlee to Cabinet appending Working Party Report)

- ^ Book (eISB), electronic Irish Statute. "electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB)". www.irishstatutebook.ie.

- ^ Ifan, Mared (30 September 2019). "National Assembly set for new bilingual name". BBC News. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Torrance, David (6 May 2020). "Senedd Cymru: Why has the National Assembly for Wales changed its name?". Commonslibrary.parliament.uk. House of Commons Library. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ da Silva, Chantal (4 March 2021). "Highest ever support for Welsh independence, new poll shows". The Independent. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

Bibliography

- Davies, Norman. The Isles: A History. (London: Macmillan, 1999. ISBN 0-333-69283-7).