History of wine

The oldest evidence of ancient wine production has been found in Georgia from c. 6000 BC (the earliest known traces of grape wine),[1][2] Iran from c. 5000 BC,[3] Greece from c. 4500 BC,[4][5] Armenia from c. 4100 BC (large-scale production),[6][7][8][9][10][11] and Sicily from c. 4000 BC.[12] The earliest evidence of fermented alcoholic beverage of rice, honey and fruit, sometimes compared to wine, is claimed in China (c. 7000 BC).[13][14][15]

The

Prehistory

Vine domestication

The origins of wine predate

Wild grapes grow in the

Following the voyages of Columbus, grape culture and wine making were transported from the Old World to the New. Spanish missionaries took viticulture to Chile and Argentina in the mid-16th century and to Baja California in the 18th. With the flood of European immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries, modern industries based on imported V. vinifera grapes were developed. The prime wine-growing regions of South America were established in the foothills of the Andes Mountains. In California the centre of viticulture shifted from the southern missions to the Central Valley and the northern counties of Sonoma, Napa, and Mendocino.[21]

Wine fermentation

The earliest archaeological evidence of wine fermentation found has been at sites in

The oldest-known

The seeds were from Vitis vinifera, a grape still used to make wine.[30] The cave remains date to about 4000 BC. This is 900 years before the earliest comparable wine remains, found in Egyptian tombs.[40][41]

The fame of

Domesticated grapes were abundant in the Near East from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, starting in 3200 BC. There is also increasingly abundant evidence for winemaking in Sumer and Egypt in the 3rd millennium BC.[42]

Legends of discovery

There are many

The Biblical Book of Genesis first mentions the production of wine by Noah following the Great Flood.

In

Antiquity

Ancient China

This article may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (December 2023) |

According to the latest research scholars stated: "Following the definition of the CNCCEF, China has been viewed as "New New World" in the world wine map, despite the fact that grape growing and wine making in China date back to between 7000BC and 9000BC. Winemaking technology and wine culture are rooted in Chinese history and the definition of "New New World" is a misnomer that imparts a Euro centric bias onto wine history and ignores fact."[13] Furthermore, the history of Chinese grape wine has been confirmed and proven to date back 9000 years (7000 BC),[13][14][15][31] including "the earliest attested use" of wild grapes in wine as well as "earliest chemically confirmed alcoholic beverage in the world", according to adjunct professor of Anthropology Patrick McGovern, the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia.[31] Professor McGovern continued: "The Jiahu discovery illustrates how you should never give up hope in finding chemical evidence for a fermented beverage from the Palaeolithic period. Research very often has big surprises in store. You might think, as I did too, that the grape wines of Hajji Firuz, the Caucasus, and eastern Anatolia would prove to be the earliest alcoholic beverages in the world, coming from the so-called "Cradle of Civilization" in the Near East as they do. But then I was invited to go to China on the other side of Asia, and came back with samples that proved to be even earlier–from around 7000 BC."[31] Additionally, Professor Hames' research stated: "The earliest wine, or fermented liquor, came from China, predating Middle Eastern alcohol by a few thousand years. Archeologists have found pottery shards showing remnants of rice and grape wine dating back to 7000 BC in Jiahu village in Henan province."[15]

Archaeologists have discovered production from native "mountain grapes" like

During the 2nd century BC,

Wine was imported again when trade with the west was restored under the

Ancient Egypt

Wine played an important role in

Wine in ancient Egypt was predominantly

Residue from five clay amphoras in Tutankhamun's tomb, however, have been shown to be that of white wine, so it was at least available to the Egyptians through trade if not produced domestically.[51]

Ancient Levant

In ancient times, the Levant region has played a vital role in the domain of winemaking. Archaeological findings, including charred grape seeds and occasionally intact berries or raisins, have been unearthed in numerous prehistoric and historic sites across Southwest Asia. Having deep historical roots dating back to at least the Bronze Age, winemaking in the Levant retained its importance as a significant regional industry until the decline of Byzantine rule in the 7th century CE. This prolonged history of winemaking significantly enriched the cultural and economic tapestry of ancient societies in the region, giving rise to numerous legends and beliefs intertwined with its consumption in the Mediterranean and Near East.[52]

The ancient

Wine held a significant and favored role within ancient Israelite cuisine, serving not only as a dietary staple but also as a crucial element of Israelite cultural and religious practices. In ancient Israel, wine found its place in both everyday use and ceremonial rituals such as sacrificial libations.[53] These traditions became an integral part of Jewish customs and celebrations, upholding the enduring importance of wine within Judaism to this very day. The abundancy of archeological remnants of facilities dedicated to the production of wine (at ancient Gibeon, for example), coupled with detailed depictions of vineyard establishment and grape varieties within the Hebrew Bible,[53][54] underscore the prominence of wine as the primary alcoholic choice for the ancient Israelites. Within the Hebrew language, a multitude of terms emerged relating to vines and the various stages of winemaking.[55] Winemaking also included the incorporation of spices, honey, herbs, and other ingredients. Following the fermentation process, the wine was meticulously stored in amphorae, often lined with protective resin coatings to ensure preservation. Jewish winemaking evolved during the Hellenistic period, with dried grapes producing sweeter, higher alcohol content wine that required dilution with water for consumption.[56]

During Late Antiquity, when the Levant was under Byzantine control, the region established itself as a renowned center for winemaking. Ashkelon and Gaza, two ancient port cities in modern-day Israel and Gaza Strip, rose to prominence as important trade centers, facilitating extensive wine exports throughout the Byzantine Empire. The writings of 4th-century CE priest Jerome vividly depicted the Holy Land's landscape adorned with sprawling vineyards. The wines of this region, as described by the 6th-century CE poet Corippus, stood out for their attributes of being white, light, and sweet.[57]

In the

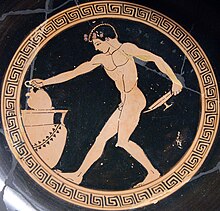

Ancient Greece

Much of modern wine culture derives from the practices of the ancient Greeks. The vine preceded both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures.[16][34] Many of the grapes grown in modern Greece are grown there exclusively and are similar or identical to the varieties grown in ancient times. Indeed, the most popular modern Greek wine, a strongly aromatic white called retsina, is thought to be a carryover from the ancient practice of lining the wine jugs with tree resin, imparting a distinct flavor to the drink.

The "Feast of the Wine" (Me-tu-wo Ne-wo) was a festival in Mycenaean Greece celebrating the "Month of the New Wine".[58][59][60] Several ancient sources, such as the Roman Pliny the Elder, describe the ancient Greek method of using partly dehydrated gypsum before fermentation and some type of lime after, in order to reduce the acidity of the wine. The Greek Theophrastus provides the oldest known description of this aspect of Greek winemaking.[61][62]

In Homeric mythology, wine is usually served in "mixing bowls" rather than consumed in an undiluted state. Dionysus, the Greek god of revelry and wine—frequently referred to in the works of Homer and Aesop—was sometimes given the epithet Acratophorus, "giver of unmixed wine".[63][64] Homer frequently refers to the "wine-dark sea" (οἶνωψ πόντος, oīnōps póntos): in lack of a name for the color blue, the Greeks would simply refer to red wine's color.

The earliest reference to a named wine is from the 7th-century BC lyrical poet

. If so, this makes Lemnió the oldest known varietal still in cultivation.For Greece, alcohol such as wine had not fully developed into the rich 'cash crop' that it would eventually become toward the peak of its reign. However, as the emphasis of viticulture increased with economic demand so did the consumption of alcohol during the years to come. The Greeks embraced the production aspect as a way to expand and create economic growth throughout the region. Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the

Ancient Persia

Ancient Thrace

The works of Homer, Herodotus and other historians of Ancient Greece refer to the ancient Thracians' love for winemaking and consumption,[74] as early as 6000 years ago.[75] the Thracians are considered the first to worshipp the god of wine called Dionysus in Greek or Zagreus in Thracian. Later this cult reached Ancient Greece.[76][77] Some consider Thrace (modern day Bulgaria) as the motherland of wine culture.[78]

Roman Empire

The

Winemaking technology improved considerably during the time of the Roman Empire, though technologies from the

Wine, perhaps mixed with herbs and minerals, was assumed to serve medicinal purposes. During Roman times, the upper classes might dissolve

Over the course of the later Empire, wine production gradually shifted to the east as Roman infrastructure and influence in the western regions gradually diminished. Production in Asia Minor, the Aegean and the Near East flourished through Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era.[18]

The oldest surviving bottle still containing liquid wine, the Speyer wine bottle, belonged to a Roman nobleman and it is dated at 325 or 350 AD.[87][88]

Medieval period

Medieval Middle East

The advent of

Christian monasteries in the

In the Levant, the Muslim conquest of the Levant suppressed winemaking after centuries of regional prominence, and the 13th-century Mamluk conquest resulted in its complete prohibition.[52]

Medieval Europe

It has been one of history's cruel ironies that the [Christian medieval]

halachically exempted from using [kosher] red wine, lest it be seized as "evidence" against them.— Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It, Project Genesis[90]

In the

A housewife of the merchant class or a servant in a noble household would have served wine at every meal, and had a selection of reds and whites alike. Home recipes for meads from this period are still in existence, along with recipes for spicing and masking flavors in wines, including the simple act of adding a small amount of honey. As wines were kept in barrels, they were not extensively aged, and thus drunk quite young. To offset the effects of heavy alcohol-consumption, wine was frequently watered down at a ratio of four or five parts water to one of wine.

One medieval application of wine was the use of snake-stones (banded agate resembling the figural rings on a snake) dissolved in wine as a remedy for snake bites, which shows an early understanding of the effects of alcohol on the central nervous system in such situations.[62]

Medieval names for types of wine included "pimentum"[92] and "

Modern era

Spread and development in the Americas

European grape varieties were first brought to what is now Mexico by the first Spanish

During the devastating phylloxera blight in late 19th-century Europe, it was found that Native American vines were immune to the pest.

Today, wine in the Americas is often associated with

Until the latter half of the 20th century, American wine was generally viewed as inferior to that of Europe. However, with the surprisingly favorable American showing at the Paris Wine tasting of 1976, New World wine began to garner respect in the land of wine's origins.

Developments in Europe

In the late 19th century, the

Australia, New Zealand and South Africa

In the context of wine, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and other countries without a wine tradition are considered New World producers. Wine production began in the Cape Province of what is now South Africa in the 1680s as a business for supplying ships. Australia's First Fleet (1788) brought cuttings of vines from South Africa, although initial plantings failed and the first successful vineyards were established in the early 19th century. Until quite late in the 20th century, the product of these countries was not well known outside their small export markets. For example, Australia exported mainly to the United Kingdom; New Zealand retained most of its wine for domestic consumption, and South Africa exported to the Kings of Europe. However, with the increase in mechanization and scientific advances in winemaking, these countries became known for high-quality wine. A notable exception to the foregoing is that the Cape Province was the largest exporter of wine to Europe in the 18th century.

East Asia

In East Asia, the first modern wine industry was Japanese wine, developed in 1874 after grapevines were brought back from Europe.[93] The earliest wine brewing companies in Japan include Suntory and Mercian.

See also

- History of Champagne

- History of Chianti

- History of French wine

- History of Portuguese wine

- History of South African wine

- History of Sherry

- History of Rioja wine

- History of the wine press

- Phoenicians and wine

- Lebanese wine

- Wine in China

- Indian wine

- Speyer wine bottle

- Wine warehouses of Bercy

References

- ^ a b "'World's oldest wine' found in 8,000-year-old jars in Georgia". BBC News. 13 November 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- PMID 29133421. [verification needed]

- ^ University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- .

- .

- ^ a b "6000-year-old winery found in Armenia – Ya Libnan". 11 January 2011.

- ^ "EIGHT OF THE WORLD'S OLDEST WINERIES".

- ISBN 9781841625553.

- ISBN 9781784724825.

- ^ "Decanter". Decanter magazine. Vol. 36, Nummers 5-8. February 2011.

- ^ "Wine 4,100 B.C. – World's Oldest Winery Discovered". 27 August 2014.

- ^ a b Tondo, Lorenzo (30 August 2017). "Traces of 6,000-year-old wine discovered in Sicilian cave". The Guardian.

- ^ hdl:10419/194558.

- ^ PMID 29518928.

- ^ ISBN 9781317548706.

- ^ a b The history of wine in ancient Greece Archived 12 July 2002 at the Wayback Machine at greekwinemakers.com

- ^ "UNESCO Pafos Archaeological Park".

- ^ OCLC 1139263254.

- Ahmad Y Hassan, Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9780062325518.

- ^ "Wine | Definition, History, Varieties, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Keys, David (28 December 2003). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Evidence of ancient wine found in Georgia a vintage quaffed some 6,000 years BC". Euronews. 21 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Georgia's Giant Clay Pots Hold An 8,000-Year-Old Secret To Great Wine, NPR.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-3033-9.

- ^ Berkowitz, Mark (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ a b "Earliest Known Winery Found in Armenian Cave". news.nationalgeographic.com. 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Armenian find is 'world's oldest winery' – Decanter". Decanter. 12 January 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Scientists discover 'oldest' winery in Armenian cave". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d [1]. Prehistoric China – The Wonders That Were Jiahu The World’s Earliest Fermented Beverage. Professor Patrick McGovern the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. Retrieved on 3 January 2017.

- PMID 15590771.

- S2CID 3892614.

- ^ a b Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece Archived 3 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine Discovery News.

- ^ "Earliest Known Winery Found in Armenian Cave". 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011.

- ^ David Keys (28 December 2003). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Mark Berkowitz (September–October 1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ a b "'Oldest known wine-making facility' found in Armenia". BBC News. BBC. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Thomas H. Maugh II (11 January 2011). "Ancient winery found in Armenia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "6,000-year-old winery found in Armenian cave (Wired UK)". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ "World's oldest winery discovered in Armenian cave". news.am. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Verango, Dan (29 May 2006). "White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb". USA Today. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ISBN 1-56025-871-3.

- ^ Eijkhoff, P. Wine in China: its historical and contemporary developments (PDF).

- ^ ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Page 101.

- ^ Wine Production in China 3000 years ago Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Zhang Qian: Opening the Silk Road". monkeytree.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ ISBN 0-8047-0720-0. Page 134–135.

- ^ Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Olga Jáuregui and Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol 33, Iss 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 98–101.

- ^ "Isis & Osiris". University of Chicago.

- ^ White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb. USA Today, 29 May 2006.

- ^ S2CID 235534373.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Nathan (2008). What Did the Ancient Israelites Eat?. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Marks, Gil (2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. pp. 616–618.

- ^ Yeivin, Z (1966). Journal of the Israel Department of Antiquities. 3. Jerusalem: Israel Department of Antiquities: 52–62.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Marks, Gil (2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. pp. 616–618.

- ^ Decker, M. (2009). Tilling the Hateful Earth: Agricultural Production and Trade in the Late Antique East. Oxford University Press. pp. 136–139.

- ^ Mycenaean and Late Cycladic Religion and Religious Architecture, Dartmouth College

- ^ T.G. Palaima, The Last days of Pylos Polity Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Université de Liège

- ^ James C. Wright, The Mycenaean feast, American School of Classical Studies, 2004, on Google books

- ^ Caley, Earle (1956). Theophrastis on Stone. Ohio State University.Online version: Gypsum/lime in wine Archived 8 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Georg Agricola, Albertus Magnus as well as newer authors such as George Frederick Kunzdescribe the many talismanic, medicinal uses of minerals and wine combined.

- ^ Pausanias, viii. 39. § 4

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Acratophorus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 14.

- ISBN 978-0-415-28073-0.

- ISBN 978-90-04-10970-4.

- ISBN 978-0-415-28073-0.

- ^ year old Mashed grapes found World's earliest evidence of crushed grapes

- ^ a b Introduction to Wine Laboratory Practices and Procedures, Jean L. Jacobson, Springer, p.84

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Brian Murray Fagan, 1996 Oxford Univ Pr, p.757

- ^ Wine: A Scientific Exploration, Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, CRC Press, p.66

- ^ Medieval France: an encyclopedia, William Westcott Kibler, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p.964

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- ^ "Ancient Thrace, the Motherland of Wine Culture | Code de Vino". Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Advertorial (17 November 2021). "Who Are the Thracians and Why Wine Was an Integral Part of Their Culture and Tradition 6000 Years Ago?". Wine Industry Advisor. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- OCLC 460134637.

- OCLC 41320191.

- ^ "Ancient Thrace, the Motherland of Wine Culture | Code de Vino". Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Jellinek, E. M. 1976. "Drinkers and Alcoholics in Ancient Rome." Edited by Carole D. Yawney and Robert E. Popham. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 37 (11): 1718-1740.

- ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ^ Dodd, Emlyn (January 2017). "Pressing Issues: A New Discovery in the Vineyard of Region I.20, Pompeii". Archeologia Classica.

- ^ Vitruvius. De architectura, I.4.2.

- ^ Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 72. Simon and Schuster 1989.

- ISBN 0203373944

- Natural History, XIV.61.

- ^ "History of Wine I". Life in Italy. 28 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ "The Roman Wine of Speyer: The oldest Wine of the World that's still liquid". Deutsches Weininstitut. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Museum scared to open ancient Roman wine". The Local – Germany edition. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- S2CID 252084558.

- ^ Rutman, Rabbi Yisrael. "Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It". Project Genesis Inc. Archived from the original on 24 December 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ Miller, Chaim. Chabad. "Rashi's Method of Biblical Commentary".

- ^

Langland, William (1885). Skeat, Walter William (ed.). The Vision of William Concerning Piers Plowman: Together with Vita de Dowel, Dobet, Et Dobest, and Richard the Redeles. Early English Text Society (Series).: Original series: 67. London: N. Trübner & Company. p. 433. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

Pigmentum, or pimentum, wine spiced, or mingled with honey, called in French piment, was formerly in high estimation.

- ISBN 978-1784724030.

Further reading

- Patrick E. McGovern (2007). Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691127842.

- Patrick E. McGovern (2010). Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520267985.

- Emlyn K. Dodd (2020). Roman and Late Antique wine production in the eastern Mediterranean. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-78969-402-4

- Muraresku, Brian C. (2020). The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name. Macmillan USA. ISBN 978-1250207142

- Magris, Gabriele; Jurman, Irena; Fornasiero, Alice; Paparelli, Eleonora; Schwope, Rachel; Marroni, Fabio; Di Gaspero, Gabriele; Morgante, Michele (21 December 2021). "The genomes of 204 Vitis vinifera accessions reveal the origin of European wine grapes". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 7240. PMID 34934047.