Homeric Hymns

The Homeric Hymns (

The hymns share compositional similarities with the

There are references to the Hymns in Greek poetry from around 600 BCE; they appear to have been used as educational texts by the early fifth century BCE, and to have been collected into a single corpus after the third century CE. Their influence on Greek literature and art was comparatively small until the third century BCE, when they were used extensively by

The Hymns were first published in print by Demetrios Chalkokondyles in 1488–1489.[b] George Chapman made the first English translation of the Hymns in 1642. The rediscovery of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter in 1777 led to a resurgence of European interest in the Hymns. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used the Hymn to Demeter as an inspiration for his 1778 melodrama Proserpina. The Hymns were also influential on the English Romantic poets of the early nineteenth century, particularly Leigh Hunt, Thomas Love Peacock and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Their influence has also been traced in the novels of James Joyce, the poetry of Ezra Pound, the films of Alfred Hitchcock and the novel Coraline by Neil Gaiman.

Composition

The hymns mostly date to the archaic period of Greek history.[2] The earliest date to the seventh century BCE;[3] most were probably composed between that century and the sixth century BCE,[2] though the Hymn to Ares is considerably later and may date from as late as the fifth century CE.[4] Although the individual hymns can rarely be dated with certainty, the longer poems (that is, Hymns 2–5) are generally considered archaic in date.[5] Scholars debate the degree to which the hymns were composed orally, as opposed to with the use of writing, and the degree of consistency or "fixity" likely to have existed between early versions of the hymns in performance.[6]

The name "Homeric Hymns" derives from the attribution, in antiquity, of the hymns to

The attribution to Homer was sometimes questioned in antiquity, such as by the rhetorician Athenaeus, who expressed his doubts about it around 200 CE.[11] Other hypotheses in ancient times included the belief that the Hymn to Apollo was the work of Kynathios of Chios, one of the Homeridae, a circle of poets claiming descent from Homer.[5] Some ancient biographies of Homer denied his authorship of the Homeric Hymns, and the hymns' comparative absence from the work of scholars based in Hellenistic (that is, post–323 BCE) Alexandria may suggest that they were no longer considered to be his work by this period.[12] However, few direct statements denying Homer's authorship of the Hymns survive from antiquity: in the second century CE, the Greek geographer Pausanias maintained their attribution to Homer.[13]

Collection and transmission

An

The grouping of the hymns into their current corpus may date to late antiquity.[3] References to the shorter poems as being within the corpus begin to be found in sources dating from the second and third centuries CE.[17] The assemblage of the thirty-three hymns listed as today "Homeric" dates to no earlier than the third century CE.[18] Between the fourth and the thirteenth centuries CE, the Homeric Hymns were generally transcribed in an edition which also contained the Hymns of Callimachus, the Orphic Hymns, the hymns of Proclus and the Orphic Argonautica.[19]

Only a few papyrus copies of the Homeric Hymns are known.

Function

The hymns vary considerably in length, between 3 and 580 surviving lines.[28] They seem originally to have functioned as preludes (prooimia) to recitations of longer works, such as epic poems.[29] Many of the hymns with a verse indicating that another song will follow, sometimes specifically a work of heroic epic.[28] Over time, however, at least some may have lengthened and been recited independently of other works.[3] The hymns which currently survive as shorter works may equally be abridgements of longer works, retaining the introduction and conclusion of a poem whose central narrative has been lost.[30]

The first known sources referring to the poems as "hymns" (

The hymns may have been composed to be recited at religious festivals, perhaps at singing contests: several directly or indirectly ask the god's support in competition.[34] Originally, they appear to have been performed by singers accompanying themselves on a stringed instrument; later, they may have been recited by an orator holding a staff.[11] They seem likely to have been performed frequently in various contexts throughout antiquity, such as at banquets or symposia.[35] Nicholas Richardson has suggested that the fifth hymn, to Aphrodite, could have been composed for performance at the court of a ruler.[17] The hymns' narrative voice has been described by Marco Fantuzzi and Richard Hunter as "communal", usually making only generalised reference to their place of composition or the identity of the speaker, making them suitable for recitation by different speakers and for different audiences.[36]

Reception

Antiquity

The Homeric Hymns are quoted comparatively rarely in ancient literature.[38] There are sporadic references to them in early Greek lyric poetry, such as the works of Pindar and Sappho.[39] The lyric poet Alcaeus composed hymns around 600 BCE to Dionysus and to the Dioscuri, which were influenced by the equivalent Homeric hymns, as possibly was Alcaeus's hymn to Hermes. The Homeric Hymn to Hermes also inspired the Ichneutae, a satyr play composed in the fifth century BCE by the Athenian playwright Sophocles.[40] Few secure references to the Hymns can be dated to the fourth century BCE, though the Thebaid of Antimachus may contain allusions to the hymns to Aphrodite, Dionysus and Hermes.[41] A few fifth-century painted vases show myths depicted in the Homeric Hymns and may have been inspired by the poems, but it is difficult to be certain whether the correspondences reflect direct contact with the Hymns or simply the commonplace nature of their underlying mythic narratives.[42]

The hymns do not appear to have been studied by the Hellenistic

The Greek philosopher Philodemus, who moved to Italy between around 80 and 70 BCE and died around 40 to 35 BCE, has been suggested as a possible originator for the movement of manuscripts of the Homeric Hymns into the Roman world, and consequently for their reception into Latin literature.[51] His own works quoted from the hymns to Demeter and Apollo.[50] In Roman poetry, the opening of Lucretius's De rerum natura, written around the mid 50s BCE, has correspondences with the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite.[52] Virgil drew upon the Homeric Hymns in the Aeneid, composed between 29 and 19 BCE. The encounter between Aeneas and his mother Venus references the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, in which Venus's Greek counterpart seduces Aeneas's father, Anchises.[53] Later in the Aeneid, the account of the theft of Hercules's cattle by the monster Cacus is based upon that of the theft of Apollo's cattle by Hermes in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes.[54]

Ovid made extensive use of the Homeric Hymns: his account of Apollo and Daphne in the Metamorphoses, published in 8 CE, references the Hymn to Apollo,[55] while other parts of the Metamorphoses make reference to the Hymn to Demeter, the Hymn to Aphrodite and the second Hymn to Dionysus.[56] Ovid's account of the abduction of Persephone in his Fasti, written and revised between 2 and around 14 CE, likewise references the Hymn to Demeter.[57] Ovid further makes use of the Hymn to Aphrodite in Heroides 16, in which Paris adapts a section of the hymn to convince Helen of his worthiness for her.[58] The Odes of Ovid's contemporary Horace also make use of the Homeric Hymns, particularly the five longer poems.[59] In the second century CE, the Greek-speaking authors Lucian and Aelius Aristides drew on the hymns: Aristides used them in his orations, while Lucian parodied them in his satirical Dialogues of the Gods.[60]

Late antiquity to Renaissance

In late antiquity, the direct influence of the Homeric Hymns was comparatively limited until the fifth century CE, during which they were quoted and adapted by the Greek-speaking poet Nonnus.[61] Other poets of the fifth century onwards, such as Musaeus Grammaticus and Coluthus, made use of them.[62] The Hymn to Hermes was a partial exception, as it was frequently taught in schools. It is possibly alluded to in an anonymous third-century poem praising a gymnasiarch named Theon, preserved by a papyrus fragment found at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt and probably written by a student for a local festival.[63] It also influenced the "Strasbourg Cosmogony", a poem composed around 350 BCE (possibly by the poet and local politician Andronicus) in commemoration of the mythical origins of the Egyptian city of Hermopolis Magna.[64] The hymns also influenced the fourth-century Christian poem The Vision of Dorotheus, and a third-century hymn to Jesus transmitted among the Sibylline Oracles.[65] They may also have been a model, alongside the hymns of Callimachus, for the fourth-century Christian hymns known as the Poemata Arcana, written by Gregory of Nazianzus.[66]

Manuscript copies of the Homeric Hymns, often bundling them with other works such as the hymns of Callimachus, continued to be made during the Byzantine period.[68] The poems were, however, only rarely referenced, and never quoted, in Byzantine literature.[69] The sixth-century poet Paul Silentiarius wrote a hexameter poem, celebrating the restoration of Hagia Sophia by the emperor Justinian I, which borrowed from the Homeric Hymn to Hermes.[70] Other, later authors, such as the eleventh-century Michael Psellos, may have drawn upon them, but it is often unclear whether their allusions are drawn directly from the Hymns or from other works narrating the same myths.[71] The Hymns have also been cited as an inspiration for the twelfth-century poetry of Theodore Prodromos.[72]

The hymns were copied and adapted widely in fifteenth-century Italy, for example by the poets Michael Marullus and Francesco Filelfo.[73] A manuscript, known by the siglum V, commissioned by the Catholic cardinal Bessarion probably in the 1460s, published the Hymns at the end of a collection of the other works then considered Homeric.[74] This arrangement became standard in subsequent editions of Homer's works, and played an important role in establishing the perceived relationship between the Hymns, the Iliad and the Odyssey.[75] The Stanze per la giostra ('Stanzas for the Joust'), written in the 1470s by Angelo Poliziano, paraphrase the second Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, and was in turn an inspiration for Sandro Botticelli's The Birth of Venus, painted in the 1480s.[76] The first printed edition (editio princeps) of the works of Homer, which included the Homeric Hymns, was made by the Florence-based Greek scholar Demetrios Chalkokondyles in 1488–1489.[75][b]

Early modern period onwards

The first English translation of the Hymns was made by George Chapman, as part of his complete translation of Homer, in 1624.[78] Although they received comparatively little attention in English poetry in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Restoration playwright and poet William Congreve published a version of the first Hymn to Aphrodite, written in heroic couplets, in 1710.[79] In 1744, he released a revised version of his 1710 Semele: An Opera, with music by George Frideric Handel and a newly-added passage of the libretto quoting Congreve's translation of the "Hymn to Aphrodite".[80] The rediscovery of the Hymn to Demeter in 1777 sparked a series of scholarly editions of the poem in Germany, and its first translations into German (in 1780) and Latin (in 1782).[81] It was also an influence on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's melodrama Proserpina, first published as a prose work in 1778.[82]

The Hymns were frequently read, praised and adapted by the English Romantic poets of the early nineteenth century. In 1814, the essayist and poet Leigh Hunt published a translation of the second Hymn to Dionysus.[83] Thomas Love Peacock adapted part of the same hymn in the fifth canto of his Rhododaphne, published posthumously in 1818.[84] In January 1818, Percy Bysshe Shelley made a translation of some of the shorter "Homeric Hymns" into heroic couplets; in July 1820, he translated the Hymn to Hermes into ottava rima.[78]

The Hymn to Demeter was particularly influential as one of the few sources, and the earliest source, for the religious rituals known as the Eleusinian Mysteries.[85] It became an important nexus of the debate into the nature of early Greek religion in early-nineteenth-century German scholarship.[86] The anthropologist James George Frazer discussed the Hymn at length in The Golden Bough, his influential 1890 work of comparative mythology and religion.[87] James Joyce made use of the same hymn, and possibly Frazer's work, in his 1922 novel Ulysses, in which the character Stephen Dedalus references "an old hymn to Demeter" while undergoing a journey reminiscent of the Eleusinian Mysteries.[88] Joyce also drew upon the Hymn to Hermes in the characterisation of both Dedalus and his companion Buck Mulligan.[89] The Cantos by Joyce's friend and mentor Ezra Pound, written between 1915 and 1960, also draw on the Hymns: Canto I concludes with parts of the hymns to Aphrodite, in both Latin and English.[90]

The first Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite has also been cited as an influence on Alfred Hitchcock's 1954 film Rear Window, particularly for the character of Lisa Freemont, played by Grace Kelly.[91] Judith Fletcher has traced allusions to the Homeric Hymn to Demeter in Neil Gaiman's 2002 children's novel Coraline and its 2009 film adaptation, arguing that the allusions in the novel's text are "subliminal" but become explicit in the film.[92]

List of the Homeric Hymns

| No. | Title | Dedicated to | Date | Surviving lines | Subject matter | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "To Dionysus" | Dionysus | c. 650 – c. 600 BCE[93] | 21 | The birth of Dionysus, and possibly also the binding of Hera and Dionysus's arrival on Olympus.[94] | [95] |

| 2 | "To Demeter" | Demeter | c. late 7th – c. early 6th century BCE[96] | 495 | The abduction of Persephone, Demeter's attempt to recover her from the Underworld, and the origin of the cult of Demeter at Eleusis. | [97] |

| 3 | "To Apollo" | Apollo | 522 BCE[98] | 546 | The foundation of Apollo's sanctuaries at Delphi and Delos: Leto's search for a place for Apollo to be born, and Apollo's search for a place for his oracle. | [99] |

| 4 | "To Hermes" | Hermes | c. second half of 6th century BCE.[100] | 580 | The first three days of Hermes' life: his abduction of the cattle of Apollo and his crafting of a tortoiseshell lyre. | [101] |

| 5 | "To Aphrodite" | Aphrodite | Unknown: generally considered among the oldest, and earlier than the Hymn to Demeter.[102] Possibly 1st half of 7th century BCE.[103] | 293 | The love of Aphrodite for the mortal hero Anchises | [104] |

| 6 | "To Aphrodite" | Aphrodite | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 21 | Aphrodite's birth, travel to Cyprus, and acceptance at the court of the gods | [106] |

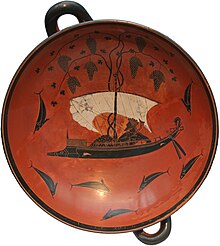

| 7 | "To Dionysus" | Dionysus | Unclear: tentatively dated to c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[107] | 59 | Dionysus's capture by pirates and transfiguration of them into dolphins | [108] |

| 8 | "To Ares"[d] | Ares | c. 200 – c. 500 CE;[110] also argued as possibly as early as the 3rd century BCE[111] | 17 | A list of Ares's epithets and a prayer to him for courage, tranquillity and moderation | [112] |

| 9 | "To Artemis" | Artemis | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 9 | A short description of Artemis as a huntress, a dancer, and the sister of Apollo | [113] |

| 10 | "To Aphrodite" | Aphrodite | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 6 | Aphrodite's beauty, and a prayer to her for musical excellence | [114] |

| 11 | "To Athena" | Athena | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 5 | Athena's role as a goddess of war, and a prayer to her for good fortune and happiness | [115] |

| 12 | "To Hera" | Hera | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 5 | Hera's beauty and honour as the sister-wife of Zeus | [116] |

| 13 | "To Demeter" | Demeter | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 3 | Invocation of Demeter and Persephone, and a prayer to Demeter to protect the singer's city | [117] |

| 14 | "To the Mother of the Gods" | Rhea or Cybele | Probably 7th century BCE[118] | 6 | Salutation to the goddess and description of her love of sound and music | [117] |

| 15 | "To Heracles the Lion-Hearted" | Heracles | Probably 6th century BCE[119] | 9 | Brief biography of Heracles, including his deification and labours | [120] |

| 16 | "To Asclepius" | Asclepius | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 5 | Asclepius's birth and role as a healer | [121] |

| 17 | "To the Dioscuri"[e] | Castor and Pollux | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 5 | The conception and birth of the Dioscuri | [123] |

| 18 | "To Hermes"[f] | Hermes | After c. 500 BCE, and later than the hymn to Apollo, but before c. 470 BCE[124] | 12 | The seduction of Maia, Hermes's mother, by Zeus | [123] |

| 19 | "To Pan" | Pan | After 500 BCE,[125] probably before 323 BCE, and probably slightly later than the hymn to Hermes[126] | 49 | Pan's wanderings through woods and mountains, his conception, birth and arrival on Olympus[127] | [128] |

| 20 | "To Hephaistos" | Hephaistos | c. 2nd half of 5th century BCE[129] | 8 | Hephaistos's teaching of craft to human beings | [130] |

| 21 | "To Apollo" | Apollo | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 5 | Apollo as a subject of song for humans and animals | [131] |

| 22 | "To Poseidon" | Poseidon | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 7 | Poseidon's role as a god of the sea, earthquakes and horses | [131] |

| 23 | "To Zeus" | Zeus | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 4 | Zeus's power and wisdom | [132] |

| 24 | "To Hestia" | Hestia | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 5 | Invitation to Hestia to enter and bless the singer's house | [133] |

| 25 | "To the Muses and Apollo"[g] | The Muses and Apollo | c. late 7th – c. 6th century BCE, probably 6th century[113] | 7 | The Muses and Apollo as the patrons of singers and musicians | [135] |

| 26 | "To Dionysus" | Dionysus | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 13 | Dionysus and the nymphs: how the nymphs raised and now follow Dionysus | [136] |

| 27 | "To Artemis" | Artemis | Probably before the 5th century BCE[113] | 22 | Artemis's prowess as a huntress, and as a dancer at Delphi | [137] |

| 28 | "To Athena" | Athena | Possibly 5th century BCE[113] | 18 | The birth of Athena from the head of Zeus | [138] |

| 29 | "To Hestia" | Hestia | c. 7th – c. 6th century BCE[105] | 13 | The honours paid to Hestia in banquets, and an invitation to Hermes and Hestia to attend the singer | [139] |

| 30 | "To Gaia, Mother of All" | Gaia | c. 500 – c. 300 BCE[113] | 19 | The abundance and blessings of the Earth | [140] |

| 31 | "To Helios" | Helios | c. 5th century BCE[129] | 19 | Helios's birth, and chariot-borne journey across the sky | [141] |

| 32 | "To Selene" | Selene | c. 5th century BCE[129] | 20 | The radiance of Selene and her conception of Pandia with Zeus | [142] |

| 33 | "To the Dioscuri" | Castor and Pollux | Possibly before 600 BCE[113] | 19 | The role of the Dioscuri as protectors of mortals, especially seafarers | [143] |

| 34 | "To Hosts"[a] | All hosts | Unknown; before 200 CE[145] | 5 | An entreaty to all hosts, reminding them of their sacred duty of hospitality (xenia) | [146] |

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ^ a b The "Hymn to Hosts" is strictly an epigram, rather than a hymn, as it does not address a deity. It is transmitted in some manuscripts of the Homeric Hymns.[144]

- ^ a b Printing of the first edition commenced in 1488, but was not completed until January 1489.[77]

- ^ Idyll 25, once attributed to Theocritus but now generally considered spurious, also alludes to the Homeric Hymn to Hermes.[46]

- ^ Claimed by Martin West as the work of the fifth-century CE philosopher Proclus: this attribution is now considered unsound on philosophical and philological grounds.[109]

- ^ An abridgement of Hymn 33.[122]

- ^ An abridgement of Hymn 4.[122]

- ^ A cento, composed from lines taken from Hesiod's epic poem, Theogony.[134]

References

- ^ Piper 1982, pp. ix, 4.

- ^ a b Price 1999, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e Pearcy 1989, p. iv.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, p. iv; Faulkner 2011b, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Richardson 2003, p. xiii.

- ^ Faulkner 2011b, pp. 3–7.

- ^ a b Richardson 2003, p. vii.

- ^ Bing 2009, p. 34; Thucydides 3.102; Pindar, Paean 7b. For Thucydides's dates, see Canfora 2006; for those of Pindar, see Eisenfeld 2022, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, p. v.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. v–vii.

- ^ a b Richardson 2003, p. xii.

- ^ Richardson 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Peirano 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Göransson 2021, p. 14.

- ^ Shapiro 2002, p. 96, n. 8.

- ^ Richardson 2010, p. 1. For the vase, see Beazley 1948.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Faulkner 2011a, p. 175.

- ^ Càssola 1975, p. lxv.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Càssola 1975, pp. lxv–lxvi; Richardson 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Barnett 2018, pp. 97–98.

- ^ West 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Richardson 2010, p. 33. West suggests that Μ should be dated after 1439.[23]

- ^ West 2011, p. 43; Barnett 2018, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Richardson 2003, p. xxiv, citing Pfeiffer 1976, p. 48.

- ^ Simelidis 2016, p. 252.

- ^ a b Richardson 2003, p. viii.

- ^ a b Bing 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Parker 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Richardson 2003, pp. xiv–xvii.

- ^ Depew 2009, p. 60.

- ^ Richardson 2003, p. xviii.

- ^ Richardson 2003, pp. x–xii.

- ^ Strauss Clay 2006, p. 7; Richardson 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Fantuzzi & Hunter 2009, p. 363.

- ^ Strauss Clay 2016, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Richardson 2003, p. xxiii.

- ^ Faulkner 2011a, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Richardson 2003, p. xxiv.

- ^ Faulkner 2016a, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Strauss Clay 2016, esp. pp. 29–32.

- ^ Petrovic 2012, p. 171.

- ^ Faulkner 2016a, p. 10.

- ^ Fantuzzi & Hunter 2009, pp. 370–371; Faulkner 2011a, p. 195 (for Idyll 17).

- ^ Faulkner 2016a, p. 13.

- ^ Faulkner 2011a, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Faulkner 2011a, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Faulkner 2011a, pp. 176.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2016a, p. 1.

- ^ Keith 2016, pp. 125–126. On Philodemus, see Fish & Sanders 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Keith 2016, n. 30. For the dates of the De rerum natura, see Volk 2010, pp. 127, 131.

- ^ Olson 2011, pp. 57–58; Gladhill 2012, p. 159.

- ^ Clauss 2016, p. 78.

- ^ Keith 2016, pp. 109–110. For the date of the Metamorphoses, see Barchiesi 2024, p. 45.

- ^ Keith 2016, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Keith 2016, pp. 113–114. For the dates of the Fasti, see Toohey 2013, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Keith 2016, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Harrison 2016, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Strolonga 2016, pp. 163–164; Vergados 2016, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Agosti 2016, pp. 221–225.

- ^ Agosti 2016, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Agosti 2016, p. 227.

- ^ Agosti 2016, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Agosti 2016, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Faulkner 2010, pp. 80, 86; Daley 2006, pp. 28–29; Ciccolella 2020, p. 220.

- ^ M. E. Schwab 2016, p. 301.

- ^ Simelidis 2016, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Simelidis 2016, p. 247.

- ^ Simelidis 2016, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Simelidis 2016, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Faulkner 2016b, p. 262.

- ^ Thomas 2016, p. 279.

- ^ Thomas 2016, pp. 281, 298.

- ^ a b Thomas 2016, p. 298.

- ^ M. E. Schwab 2016, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Sarton 2012, p. 153.

- ^ a b Richardson 2016, p. 325.

- ^ Richardson 2016, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Richardson 2016, pp. 336–337.

- ^ A. Schwab 2016, p. 346, n. 12.

- ^ Bodley 2016, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Richardson 2016, p. 326.

- ^ Richardson 2016, p. 326. For Rhododaphne, see Barnett 2018, p. 4

- ^ A. Schwab 2016, p. 346.

- ^ A. Schwab 2016, p. 348.

- ^ Carpentier 2013, p. 71.

- ^ Carpentier 2013, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Fraser 1999, pp. 545–547.

- ^ Haynes 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Padilla 2018, p. 229.

- ^ Fletcher 2019, pp. 117–119.

- ^ West 2011, p. 34.

- ^ West 2011, pp. 29, 31–32.

- ^ West 2011.

- ^ Foley 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Foley 2013.

- ^ Burkert 1979, p. 61; Graziosi 2002, p. 206; Nagy 2011, pp. 286–287.

- ^ de Jong 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Vergados 2012, p. 147.

- ^ Vergados 2012.

- ^ Peels 2015, p. 24.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Faulkner 2008; Olson 2012; Rayor 2014, pp. 75–85; Nagy 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Price 1999, p. 45 (dating the Homeric Hymns in general).

- ^ Clark 2015, p. 36.

- ^ Jaillard 2011, note 2.

- ^ Jaillard 2011.

- ^ West 1970; van den Berg 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Faulkner 2011b, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Rayor 2014, p. 139.

- ^ West 1970.

- ^ a b c d e f Athanassakis 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Clark 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 295–296; Powell 2022, p. 36.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 114–115; Tsagalis 2022, p. 504.

- ^ a b Pearcy 1989, pp. 5, 28.

- ^ Dillon 2003, p. 155.

- ^ Ogden 2021, p. xxvi.

- ^ Allen & Sikes 1904, p. 253; Barker & Christensen 2021, pp. xxvi, 276, 285, 292, 333, 388, 392.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 6, 29.

- ^ a b Pearcy 1989, p. 30.

- ^ a b Pearcy 1989, pp. 6, 30.

- ^ Faulkner 2011b, p. 15; Richardson 2010, p. 1 (for the terminus ante quem).

- ^ Pearcy 1989, p. 31; Thomas 2011, p. 172.

- ^ Thomas 2011, p. 172.

- ^ Thomas 2011, p. 159.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 7–8, 31–34; Thomas 2011.

- ^ a b c Faulkner 2011b, p. 16.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 8, 34.

- ^ a b Pearcy 1989, pp. 8, 35.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 8–9, 36.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 9, 36–37.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 9, 37.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 11–12, 41–42.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 12, 42–43.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 12, 44–45.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, pp. 13, 45–46.

- ^ Pearcy 1989, p. iv; Rayor 2014, p. 149.

- ^ Athanassakis 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Rayor 2014, p. 149.

Bibliography

- Agosti, Gianfranco (2016). "Praising the God(s): Homeric Hymns in Late Antiquity". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 221–240. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Allen, Thomas William; Sikes, Edward Ernest (1904). The Homeric Hymns. London: Macmillan. OCLC 978029978.

- Athanassakis, Apostolos N. (2004). The Homeric Hymns (2nd ed.). Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801879838.

- Barchiesi, Alessandro (2024). "Introduction". In Barchiesi, Alessandro; Rosati, Gianpiero (eds.). A Commentary on Ovid's Metamorphoses. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–48. ISBN 9780521895798.

- Barker, Elton; Christensen, Joel (2021). "Epic". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Heracles. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 283–300. ISBN 9780190651015.

- Barnett, Suzanne L. (2018). Romantic Paganism: The Politics of Ecstasy in the Shelley Circle. Cham: Springer. ISBN 9783319547237.

- JSTOR 500415.

- Bing, Peter (2009). The Scroll and the Marble: Studies in Reading and Reception in Hellenistic Poetry. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472116324.

- Bodley, Lorraine Byrne (2016). "From Mythology to Social Politics: Goethe's Proserpina". In Vlastos, George; Levidou, Katerina; Romanou, Katy (eds.). Musical Receptions of Greek Antiquity: From the Romantic Era to Modernism. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 35–67. ISBN 9781443896566.

- ISBN 9783110077988.

- Canfora, Luciano (2006). "Biographical Obscurities and Problems of Composition". In Rengakos, Antonios; Tsakmakis, Antonis (eds.). Brill's Companion to Thucydides. Leiden: Brill. pp. 3–32. ISBN 9789047404842.

- Carpentier, Martha C. (2013) [1998]. Ritual, Myth and the Modernist Text: The Influence of Jane Ellen Harrison on Joyce, Eliot and Woolf. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781134389506.

- Càssola, Filippo (1975). Inni Omerici [Homeric Hymns] (in Italian). Milan: Fondazione Lorenzo Valla. OCLC 2719946.

- Ciccolella, Federica (2020). "Maximos Margounios (c. 1549–1602), His Anacreontic Hymns, and the Byzantine Revival in Early Modern Germany". In Constantinidou, Natasha; Lamers, Han (eds.). Receptions of Hellenism in Early Modern Europe: 15th–17th Centuries. Leiden: Brill. pp. 215–232. ISBN 9789004343856.

- Clark, Nora (2015). Aphrodite and Venus in Myth and Mimesis. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443876780.

- Clauss, James J. (2016). "The Hercules and Cacus Episode in Augustan Literature: Engaging the Homeric Hymn to Hermes in Light of Callimachus' and Apollonius' Reception". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 55–78. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Daley, Brian (2006). Gregory of Nazianzus. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781134807277.

- ISBN 9789004224384. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Depew, Mary (2009) [1970]. "Enacted and Represented Dedications: Genre and Greek Hymn". In Depew, Mary; ISBN 9780674034204.

- Dillon, Matthew (2003) [2002]. Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781134365098.

- Eisenfeld, Hanne (2022). Pindar and Greek Religion: Theologies of Mortality in the Victory Odes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108924351.

- Fantuzzi, Marco; ISBN 9780511482151.

- Faulkner, Andrew (2008). The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite: Introduction, Text, and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191553424.

- Faulkner, Andrew (2010). "St. Gregory of Nazianzus and the Classical Tradition: The Poemata Arcana qua Hymns". Philologus. 154 (1): 78–87. .

- Faulkner, Andrew (2011a). "The Collection of Homeric Hymns: From the Seventh to the Third Centuries BC". In Faulkner, Andrew (ed.). The Homeric Hymns: Interpretative Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–205. ISBN 9780199589036.

- Faulkner, Andrew (2011b). "Introduction: Modern Scholarship on the Homeric Hymns: Foundational Issues". In Faulkner, Andrew (ed.). The Homeric Hymns: Interpretative Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–28. ISBN 9780199589036.

- Faulkner, Andrew (2016a). "Introduction". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Faulkner, Andrew (2016b). "Theodoros Podromos' Historical Poems: A Hymnic Celebration of John II Komnenos". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 261–274. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Fish, Jeffrey; Sanders, Kirk R. (2011). "Introduction". In Fish, Jeffrey; Sanders, Kirk R. (eds.). Epicurus and the Epicurean Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 9780511921704.

- Fletcher, Judith (2019). Myths of the Underworld in Contemporary Culture: The Backward Gaze. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191821288.

- ISBN 9781400849086.

- Fraser, Jennifer (1999). "Intertextual Turnarounds: Joyce's Use of the Homeric 'Hymn to Hermes'". James Joyce Quarterly. 36 (3): 541–557. JSTOR 25474056.

- Gladhill, C. W. (2012). "Sons, Mothers, and Sex: Aeneid 1.314–20 and the 'Hymn to Aphrodite' Reconsidered". Vergilius. 58: 159–168. JSTOR 43186313.

- Göransson, Kristian (2021). "Francavilla di Sicilia: A Greek Settlement in the Hinterland of Naxos". In Karivieri, Arja; Prescott, Christopher; Göransson, Kristian; Campbell, Peter; Tusa, Sebastiano (eds.). Trinacria, 'An Island Outside Time': International Archaeology in Sicily. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 13–18. ISBN 9781789255942.

- ISBN 9780521809665.

- ISBN 9780191795510.

- Haynes, Kenneth (2007). "Modernism". In Kallendorf, Craig W. (ed.). A Companion to the Classical Tradition. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 101–114. ISBN 9781405122948.

- Jaillard, Dominique (2011). "The Seventh Homeric Hymn to Dionysus: An Epiphanic Sketch". In Faulkner, Andrew (ed.). The Homeric Hymns: Interpretative Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 113–150. ISBN 9780199589036.

- Keith, Alison (2016). "The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite in Ovid and Augustan Literature". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 109–126. ISBN 9780191795510.

- ISBN 9780199589036.

- Nagy, Gregory (12 December 2018). "Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite". The Center for Hellenic Studies. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- Ogden, Daniel (2021). "Introduction". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Heracles. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xxi–xxxii. ISBN 9780190650988.

- Olson, S. Douglas (2011). "Immortal Encounters: Aeneid 1 and the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite". Vergilius. 57: 55–61. JSTOR 41587395.

- Olson, S. Douglas (2012). The "Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite" and Related Texts: Text, Translation and Commentary. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110260748.

- Padilla, Mark William (2018). Classical Myth in Alfred Hitchcock's Wrong Man and Grace Kelly Films. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498563512.

- Parker, Robert (1991). "The Hymn to Demeter and the Homeric Hymns". Greece & Rome. 38 (1): 1–17. JSTOR 643104.

- Pearcy, Lee T. (1989). The Shorter Homeric Hymns. Bryn Mawr Greek Commentaries. Bryn Mawr: Bryn Mawr Commentaries. ISBN 0929524624.

- Peels, Saskia (2015). Hosios: A Semantic Study of Greek Piety. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004304277.

- Peirano, Irene (2012). The Rhetoric of the Roman Fake: Latin Pseudepigrapha in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511732331.

- Petrovic, Ivana (2012). "Rhapsodic Hymns and Epyllia". In Baumbach, Manuel; Bär, Silvio (eds.). Brill's Companion to Greek and Latin Epyllion and Its Reception. Leiden: Brill. pp. 149–176. ISBN 9789004233058.

- OCLC 633665677.

- Piper, David (1982). The Image of the Poet: British Poets and Their Portraits. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198173652. Retrieved 28 March 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ISBN 9780520391697.

- Price, Simon R. F. (1999). Religions of the Ancient Greeks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521388672.

- Rayor, Diane J. (2014) [2004]. The Homeric Hymns: A Translation, with Introduction and Notes (Updated ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520282117– via Internet Archive.

- Richardson, Nicholas (2003). The Homeric Hymns. Penguin Classics. Translated by Cashford, Jules. London: Penguin. pp. vii–xxxv. ISBN 9780140437829.

- Richardson, Nicholas (2010). Three Homeric Hymns to Apollo, Hermes, and Aphrodite. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521451581.

- Richardson, Nicholas (2016). "'Those Miraculous Effusions of Genius': The Homeric Hymns Seen Through the Eyes of English Poets". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 325–344. ISBN 9780191795510.

- ISBN 9780486144986.

- Schwab, Andreas (2016). "The Reception of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter in Romantic Heidelberg: J. H. Voss and 'the Eleusinian Document'". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 345–366. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Schwab, M. Elisabeth (2016). "The Rebirth of Venus: The Homeric Hymns to Aphrodite and Poliziano's Stanze". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 301–324. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Shapiro, H. Alan (2002). "Demeter and Persephone in Western Greece: Migrations of Myth and Cult". In Bennett, Michael; Paul, Aaron J.; Iozzo, Mario (eds.). Magna Graecia: Greek Art from South Italy and Sicily. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art. pp. 82–97. ISBN 9780940717718.

- Simelidis, Christos (2016). "On the Homeric Hymns in Byzantium". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 243–260. ISBN 9780191795510.

- ISBN 1853996920.

- ISBN 9780191795510.

- Strolonga, Polyxeni (2016). "The Homeric Hymns Turn into Dialogues: Lucian's Dialogues of the Gods". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 145–164. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Thomas, Oliver (2011). "The Homeric Hymn to Pan". In Faulkner, Andrew (ed.). The Homeric Hymns: Interpretative Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 151–173. ISBN 9780199589036.

- Thomas, Oliver (2016). "Homeric and/or Hymns: Some Fifteenth-Century Approaches". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 277–300. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Toohey, Peter (2013) [1996]. Epic Lessons: An Introduction to Ancient Didactic Poetry. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781135035341.

- Tsagalis, Christos (2022). Early Greek Epic: Language, Interpretation, Performance. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110981384.

- van den Berg, Rudolphus Maria (2001). Proclus' Hymns: Essays, Translations, Commentary. Philosophia Antiqua. Vol. 90. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004122362.

- Vergados, Athanassios (2012). The "Homeric Hymn to Hermes": Introduction, Text and Commentary. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110259704.

- Vergados, Athanassios (2016). "The Reception of the Homeric Hymns in Aelius Aristides". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.). The Reception of the Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 165–186. ISBN 9780191795510.

- Volk, Katharina (2010). "Lucretius's Prayer for Peace and the Date of De Rerum Natura". The Classical Quarterly. 60 (1): 127–131. JSTOR 40984743.

- JSTOR 637428.

- ISBN 9780199589036.