Homo heidelbergensis

| Homo heidelbergensis Temporal range:

Middle Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

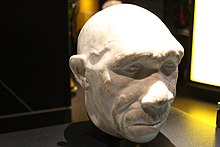

| The type specimen Mauer 1

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. heidelbergensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo heidelbergensis Schoetensack, 1908

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Homo heidelbergensis (also H. erectus heidelbergensis,

H. heidelbergensis is regarded as a

The Middle Pleistocene of Africa and Europe features the advent of Late

Taxonomy

Research history

The first fossil,

million years ago ) |

Though H. erectus is still maintained as a highly variable, widespread and long-lasting species, it is still much debated whether or not sinking all Middle Pleistocene remains into it is justifiable. Mayr's lumping of H. heidelbergensis was first opposed by American anthropologist

Further work most influentially by Stringer, palaeoanthropologist

In 1976 at

Classification

In palaeoanthropology, the

Regarding the Middle Pleistocene European remains, some are more firmly placed on the Neanderthal line (namely

In 2021, Canadian anthropologist Mirjana Roksandic and colleagues recommended the complete dissolution of H. heidelbergensis and "H. rhodesiensis", as the name rhodesiensis honours English

Evolution

H. heidelbergensis is thought to have descended from African H. erectus — sometimes classified as Homo ergaster — during the first early expansions of hominins out of Africa beginning roughly 2 million years ago. Those that dispersed across Europe and stayed in Africa evolved into H. heidelbergensis or speciated into H. heidelbergensis in Europe and "H. rhodesiensis" in Africa, and those that dispersed across East Asia evolved into H. erectus s. s.[5] The exact derivation from an ancestor species is obfuscated by a long gap in the human fossil record near the end of the Early Pleistocene.[19] In 2016, Antonio Profico and colleagues suggested that 875,000-year-old skull materials from the Gombore II site of the Melka Kunture Formation, Ethiopia, represent a transitional morph between H. ergaster and H. heidelbergensis, and thus postulated that H. heidelbergensis originated in Africa instead of Europe.[19]

According to genetic analysis, the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthal split into a modern human line, and a Neanderthal/Denisovan line, and the latter later split into Neanderthal and Denisovans. According to

In 1997, Spanish archaeologist

Human dispersal beyond

In 2023 a genomics analysis of over 3000 living individuals indicated that Homo sapiens' ancestral population was reduced to less than 1300 individuals between 800,000 and 900,000 years ago. Prof Giorgio Manzi, an anthropologist at Sapienza University of Rome, suggested that this bottleneck could have triggered the evolution of Homo heidelbergensis.[31][32]

Anatomy

Skull

In comparison to Early Pleistocene H. erectus/ergaster, Middle Pleistocene humans have a much more modern human-like face. The nasal opening is set completely vertically in the skull, and the anterior nasal sill can be crested or sometimes a prominent spine. The incisive canals (on the roof of the mouth) open near the teeth, and are orientated like those of more recent human species. The frontal bone is broad, the parietal bone can be expanded, and the squamous part of temporal bone is high and arched, which could all be related to increasing brain size. The sphenoid bone features a spine extending downwards, and the articular tubercle on the underside of the skull can jut out prominently as the surface behind the jaw hinge is otherwise quite flat.[33]

In 2004, Rightmire estimated the brain volumes of ten Middle Pleistocene humans variously attributable to H. heidelbergensis—from Kabwe, Bodo, Ndutu, Dali, Jinniushan, Petralona, Steinheim, Arago, and two from SH. This set gives an average volume of about 1,206 cc, ranging from 1,100 to 1,390 cc. He also averaged the brain volumes of 30 H. erectus/ergaster specimens, spanning nearly 1.5 million years from across East Asia and Africa, as 973 cc, and thus concluded a significant jump in brain size, though conceded brain size was extremely variable ranging from 727 to 1,231 cc depending on the time period, geographic region, and even between individuals within the same population (the last one probably due to notable sexual dimorphism with males much bigger than females).[33] In comparison, for modern humans, brain size averages 1,270 cc for males and 1,130 cc for females;[34] and for Neanderthals 1,600 cc for males and 1,300 cc for females.[35][36][37]

In 2009, palaeontologists Aurélien Mounier, François Marchal and Silvana Condemi published the first differential diagnosis of H. heidelbergensis using the Mauer mandible, as well as material from Tighennif, Algeria; SH, Spain; Arago, France; and

Size

Trends in body size through the Middle Pleistocene are obscured due to a general lack of limb bones and non-skull (post-cranial) remains. Based on the lengths of various

If these specimens are representative of their respective continents, they would suggest that above-medium to tall people were prevalent throughout the Middle Pleistocene Old World. If this is the case, then most all populations of any archaic human species would have generally averaged to 165–170 cm (5 ft 5 in – 5 ft 7 in) in height. Early modern humans were notably taller, with the Skhul and Qafzeh remains averaging 185.1 cm (6 ft 1 in) for males and 169.8 cm (5 ft 7 in) for females, an average of 177.5 cm (5 ft 10 in), possibly to increase the energy-efficiency of long-distance travel with longer legs.[38]

A conspicuously massive proximal (upper half) femur was recovered from Berg Aukas Mine, Namibia, about 20 km (12 mi) east of Grootfontein. It was originally estimated to have been from a male as much as 93 kg (205 lb) in life, but its exorbitant size is now proposed to be the consequence of an extraordinarily vigorous early-life activity level while an otherwise ordinary person was maturing. If so, the individual from the Berg Aukas Mine would probably have had proportions similar to Kabwe 1.[39]

Build

The human

The

Pathology

On the left side of its face, an SH skull (Skull 5) presents the oldest-known case of orbital cellulitis (eye infection which developed from an abscess in the mouth). This probably caused sepsis, killing the individual.[41][42][43]

A male SH pelvis (Pelvis 1), based on joint degeneration, may have lived for more than 45 years, making him one of the oldest examples of this demographic in the human fossil record. The frequency of 45-plus individuals gradually increases with time, but has overall remained quite low throughout the Palaeolithic. He similarly had the age-related maladies lumbar

An adolescent SH skull (Cranium 14) was diagnosed with lambdoid single suture craniosynostosis (immature closing of the left lambdoid suture, leading to skull deformities as development continued). This is a rare condition, occurring in less than 6 out of every 200,000 individuals in modern humans. The individual died around the age of 10, suggesting it was not abandoned due its deformity as has been done in historical times, and received the same quality of care as any other child.[45]

Culture

Food

Middle Pleistocene communities in general seem to have eaten big game at a higher frequency than predecessors, with meat becoming an essential dietary component. Diet could overall be varied—for example the inhabitants of Terra Amata seem to have been mainly eating deer, but also elephants, boar, ibex, rhino and aurochs. African sites commonly yield bovine and horse bones. Though carcasses may have simply been scavenged, some Afro-European sites show specific targeting of a single species, which more likely indicates active hunting; for example: Olorgesailie, Kenya, which has yielded over 50 to 60 individual baboons (Theropithecus oswaldi); and Torralba and Ambrona in Spain which have an abundance of elephant bones (though also rhino and large hoofed mammals). The increase in meat subsistence could indicate the development of group hunting strategies in the Middle Pleistocene. For instance, at Torralba and Ambrona, the animals may have been run into swamplands before being killed, entailing encircling and driving by a large group of hunters in a coordinated and organised attack. Exploitation of aquatic environments is generally quite lacking, despite some sites being in close proximity to the ocean, lakes or rivers.[47]

Plants were probably also frequently consumed, including seasonally available ones, but the extent of their exploitation is unclear as they do not fossilise as well as animal bones. The Schöningen site, Germany, has over 200 plants in the vicinity which are either edible raw or when cooked.[48]

Art

Upper Palaeolithic modern humans are well known for having etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value. As of 2018, only 27 Middle and Lower Palaeolithic objects have been postulated to have symbolic etching, out of which some have been refuted as having been caused by natural or otherwise non-symbolic phenomena (such as the fossilisation or excavation processes). The Lower Palaeolithic ones are: a 400,000 to 350,000 years old bone from Bilzingsleben, Germany; three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; a 250,000-year-old pebble from Markkleeberg, Germany; 18 roughly 200,000-year-old pebbles from Lazaret (near Terra Amata); a roughly 200,000-year-old lithic from Grotte de l'Observatoire, Monaco and a 200- to 130-thousand-year-old pebble from Baume Bonne, France.[49]

In the mid-19th century, French archaeologist Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes began excavation at St. Acheul, Amiens, France, (the area where the Acheulian was defined), and, in addition to hand axes, reported perforated sponge fossils (Porosphaera globularis) which he considered to have been decorative beads. This claim was completely ignored. In 1894, English archaeologist Worthington George Smith discovered 200 similar perforated fossils in Bedfordshire, England, and also speculated that their function was beads, though he made no reference to Boucher de Perthes' find, possibly because he was unaware of it. In 2005, Robert Bednarik reexamined the material, and concluded that—because all the Bedfordshire P. globularis fossils are sub-spherical and range 10–18 mm (0.39–0.71 in) in diameter, despite this species having a highly variable shape—they were deliberately chosen. They appear to have been bored through completely or almost completely by some parasitic creature (i. e., through natural processes), and were then percussed on what would have been the more closed-off end to fully open the hole. He also found wear facets which he speculated were begotten from clacking against other beads when they were strung together and worn as a necklace.[50] In 2009, Solange Rigaud, Francisco d'Errico and colleagues noticed that the modified areas are lighter in colour than the unmodifed, suggesting they were inflicted much more recently such as during excavation. They were also unconvinced that the fossils could be confidently associated with the Acheulian artefacts from the sites, and suggested that—as an alternative to archaic human activity—apparent size-selection could have been caused by either natural geological processes or 19th-century collectors favouring this specific form.[51]

Early modern humans and late Neanderthals (the latter especially after 60,000 years ago) made wide use of red ochre for presumably symbolic purposes as it produces a blood-like colour, though ochre can also have a functional medicinal application. Beyond these two species, ochre usage is recorded at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, where two red ochre lumps have been found; Ambrona where an ochre slab was trimmed down into a specific shape; and Terra Amata where 75 ochre pieces were heated to achieve a wide colour range from yellow to red-brown to red. These may exemplify early and isolated instances of colour preference and colour categorisation, and such practices may not have been normalised yet.[52]

In 2006, Eudald Carbonell and Marina Mosquera suggested the Sima de los Huesos (SH) hominins were buried by people rather than being the victims of some catastrophic event such as a cave-in, because young children and infants are absent which would be unexpected if this were a single and complete family unit. The SH humans are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality quartzite (rarely used in the region), and so Carbonell and Mosquera postulated this was purposefully and symbolically placed with the bodies as some kind of grave good. Supposed evidence of symbolic graves would not surface for another 300,000 years.[53]

Technology

Stone tools

The Lower Palaeolithic (Early Stone Age) comprises the

The transition is indicated by the production of smaller, thinner, and more symmetrical hand axes (though thicker, less refined ones were still produced). At the 500,000-year-old

With either method, knappers (tool makers) would have had to have produced some item indirectly related to creating the desired product (hierarchical organisation), which could represent a major cognitive development. Experiments with modern humans have shown that platform preparation cannot be learned through purely observational learning, unlike earlier techniques, and could be indicative of well developed teaching methods as well as self-regulated learning. At Boxgrove, the knappers used not only stone but also bone and antler to make hammers, and the use of such a wide range of raw materials could speak to advanced planning capabilities as stoneworking requires a much different skillset to work and gather materials for than boneworking.[54]

The

Fire and construction

Despite apparent pushes into colder climates, evidence of fire is scarce in the archaeological record until 400 to 300 thousand years ago. Though it is possible fire remnants simply degraded, long and overall undisturbed occupation sequences such as at Arago or Gran Dolina conspicuously lack convincing evidence of fire usage. This pattern could possibly indicate the invention of ignition technology or improved fire maintenance techniques at this time, and that fire was not an integral part of people's lives before then in Europe. In Africa, on the other hand, humans may have been able to frequently scavenge fire as early as 1.6 million years ago from natural wildfires, which occur much more often in Africa, thus possibly (more or less) regularly using fire. The oldest established continuous fire site beyond Africa is the 780,000-year-old

In Europe, evidence of constructed dwelling structures—classified as firm surface huts with solid foundations built in areas mostly sheltered from the weather—has been recorded since the

Spears

The appearance of repeated fire usage—earliest in Europe from Beeches Pit, England, and Schöningen, Germany—roughly coincides with hafting technology (attaching stone points to spears) best exemplified by the Schöningen spears.[57] These nine wooden spears and spear fragments—in addition to a lance, and a double-pointed stick—date to 300,000 years ago and were preserved along a lakeside. The spears vary from 2.9–4.7 cm (1.1–1.9 in) in diameter, and may have been 210–240 cm (7–8 ft) long, overall similar to present day competitive javelins. The spears were made of soft spruce wood, except for spear 4 which was (also soft) pine wood.[3] This contrasts with the Clacton spearhead from Clacton-on-Sea, England, perhaps roughly 100,000 years older, which was made of hard yew wood. The Schöningen spears may have had a range of up to 35 m (115 ft),[3] though would have been more effective short range within about 5 m (16 ft), making them effective distance weapons either against prey or predators. Besides these two localities, the only other site which provides solid evidence of European spear technology is the 120,000-year-old Lehringen site, district of Verden, in Lower Saxony, Germany, where a 238 cm (8 ft) yew spear was apparently lodged in an elephant.[59] In Africa, 500,000-year-old points from Kathu Pan 1, South Africa, may have been hafted onto spears. Judging by indirect evidence, a horse scapula from the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove shows a puncture wound consistent with a spear wound. Evidence of hafting (in both Europe and Africa) becomes much more common after 300,000 years.[60]

Language

The SH humans had a modern humanlike

See also

- Altamura Man

- Ceprano Man

- Dmanisi hominins

- Early European modern humans

- Homo antecessor

- Homo rhodesiensis

- Swanscombe Heritage Park

- Tautavel Man

- Tunel Wielki

References

- ^ e.g. Theodor C. H. Cole, Wörterbuch der Tiernamen: Latein-Deutsch-Englisch / Deutsch-Latein-Englisch, 2nd ed., Spinger: Heidelberg, 2015, p. 210: „Homo heidelbergensis (Homo erectus heidelbergensis) Heidelbergmensch Heidelberg man“; Manfred Eichhorn (ed.), Langenscheidt Routledge: German Dictionary of Biology / Wörterbuch Biologie Englisch: Volume/Band 2: English-German / Englisch-Deutsch, 2nd ed., Langenscheidt: Berlin / Routledge: London & New York, 1999, p. 373: „Heidelberg man (Evol) Homo erectus heidelbergensis, Heidelbergmensch m“

- ^ "Prehistoric Cultures. Homo sapiens heidelbergensis". University of Minnesota Duluth. 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-951693-99-2.

- ^ Harvati, K. (2007). "100 years of Homo heidelbergensis – life and times of a controversial taxon" (PDF). Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte. 16: 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ PMID 19249816.

- ISBN 9781118332375.

- ^ S2CID 25601948.

- ^ S2CID 205826399.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 24650901.

- ^ "Homo heidelbergensis" (in German). Sammlung des Instituts für Geowissenschaften. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

Hierzu zählte noch im Jahr 2010 auch das Geologisch-Paläontologische Institut der Universität Heidelberg, das den Unterkiefer seit 1908 verwahrt und ihn als Homo erectus heidelbergensis auswies. Inzwischen wird er jedoch auch in Heidelberg als Homo heidelbergensis bezeichnet, siehe

[In 2010, this also included the Geological-Palaeontological Institute of the University of Heidelberg, which has kept the lower jaw since 1908 and identified it as Homo erectus heidelbergensis. In the meantime, however, it is also referred to as Homo heidelbergensis in Heidelberg, see] - S2CID 225069666.

- S2CID 4467094.

- S2CID 4420496.

- S2CID 214736650.

- S2CID 4432091.

- PMID 6412559.

- PMID 6410925.

- ^ PMID 26583275.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link) (Convenience link - S2CID 11442202.

- .

- S2CID 26701026. Archived from the original(PDF) on 13 October 2015.

- PMID 34710249.

- PMID 33465331.

- S2CID 250071605.

- S2CID 4467094.

- S2CID 31088294. Archived from the original(PDF) on 7 February 2020.

- .

... a speciation event could have occurred in Africa/Western Eurasia, originating a new Homo clade [...] Homo antecessor [...] could be a side branch of this clade placed at the westernmost region of the Eurasian continent.

- S2CID 214736611.

- .

- ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the originalon 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- S2CID 261396309.

- ^ PMID 15160365.

- S2CID 21705705.

- ISBN 978-0-12-261920-5.

- ISBN 978-0-471-84376-4.

- S2CID 36974955.

- PMID 22196156.

- ISBN 9781139096164.

- ^ PMID 26324920.

- PMID 22567060.

- ISSN 1755-375X.

- ISSN 1040-6182.

- PMID 20937858.

- PMID 19332773.

- PMID 7785727.

- PMID 16468210.

- PMID 26596728.

- PMID 29718916.

- ^ Bednarik, R. G. (2005). "More on Acheulian beads" (PDF). Rock Art Research. 22 (2): 210–212. (Convenience link)

- .

- S2CID 88099778.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- PMID 20042224.

- ^ PMID 21402905.

- JSTOR 26294864.

- PMID 26442632.

- S2CID 206544031. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 February 2019.

- ^ PMID 17804038.

- .

External links

- Homo heidelbergensis – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- Homepage of Mauer 1 Club (in German)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Archaeological Site of Atapuerca

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).