House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau (

Several members of the house served during the Eighty Years war and after as stadtholder ("governor"; Dutch: stadhouder) during the Dutch Republic. However, in 1815, after a long period as a republic, the Netherlands became a monarchy under the House of Orange-Nassau.

The dynasty was established as a result of the marriage of

Origins

The House of Orange-Nassau stems from the younger Ottonian Line. The first of this line to establish himself in the Netherlands was

A nobleman's power was often based on his ownership of vast tracts of land and lucrative offices. It also helped that much of the lands that the House of Orange-Nassau controlled sat under one of the commercial and mercantile centres of the world (see below under

Eighty Years' War

Although

William was succeeded by his second son

17th century

Expansion of dynastic power

Maurice died unmarried in 1625 and left no legitimate children. He was succeeded by his half-brother

Exile and resurgence

Frederick Henry died in 1647 and his son succeeded him. As the

The Dutch Republic was attacked by France and England in 1672. The military function of stadtholder was no longer superfluous, and with the support of the

Position in the Dutch Republic in the 17th century

The house of Orange-Nassau was relatively unlucky in establishing a hereditary dynasty in an age that favoured hereditary rule. The Stuarts and the Bourbons came to power at the same time as the Oranges, the Vasas and Oldenburgs were able to establish a hereditary kingship in Sweden and Denmark, and the Hohenzollerns were able to set themselves on a course to the rule of Germany. The House of Orange was no less gifted than those houses, in fact, some might argue more so, as their ranks included some the foremost statesmen and captains of the time. A 104 years separated the death of William the Silent from the accession of his great-grandson, William III, as King of England. Although the institutions of the United Provinces became more republican and entrenched as time went on, William the Silent had been offered the countship of Holland and Zealand, and only his assassination prevented his accession to those offices. This fact did not go unforgotten by his successors.[1]: 28–31, 64, 71, 93, 139–141

The Prince of Orange was also not just another noble among equals in the Netherlands. First, he was the traditional leader of the nation in war and in rebellion against Spain. He was uniquely able to transcend the local issues of the cities, towns and provinces. He was also a sovereign ruler in his own right (see Prince of Orange article). This gave him a great deal of prestige, even in a republic. He was the center of a real court like the Stuarts and Bourbons, French speaking, and extravagant to a scale. It was natural for foreign ambassadors and dignitaries to present themselves to him and consult with him as well as to the States General to which they were officially credited. The marriage policy of the princes, allying themselves twice with the Royal Stuarts, also gave them acceptance into the royal caste of rulers.[9]: 76–77, 80

Besides showing the relationships among the family, the family tree below also points out an extraordinary run of bad luck. In the 211 years from the death of William the Silent to the conquest by France, there was only one time that a son directly succeeded his father as Prince of Orange, Stadholder and Captain-General without a minority (William II). When the Oranges were in power, they also tended to settle for the actualities of power, rather than the appearances, which increasingly tended to upset the ruling regents of the towns and cities. On being offered the dukedom of Gelderland by the States of that province, William III let the offer lapse as liable to raise too much opposition in the other provinces.[9]: 75–83

-

The collateral house of Nassau: the four brothers of Willem I, prince of Orange: Jan (1536–1606), sitting, Hendrik (1550–1574), Adolf (1540–1568) and Lodewijk (1538–1574), counts of Nassau.

-

"The Nassau Cavalcade", members of the House of Orange-Nassau on parade in 1621 from an engraving by Willem Delff. From left to right in the first row:Prince Frederick Henry, between Maurice and Frederick Henry is William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg.[10]

-

Willem II (1626–50), prince of Orange, and his wife Princess Maria Stuart of England (1631–60).

-

Princes of the collateral House of Nassau-Dietz from the Stadhouderlijk Hof (nowadays called Princessehof Ceramics Museum) in Leeuwarden, H.Prince of Nassau, Henry Casimir, Prince of Nassau, George, Prince of Nassau, and Willem Frederick, Prince of Nassau_Dietz

18th century

Second Stadtholderless period

The regents found that they had suffered under the powerful leadership of William III as the ruler of the Netherlands and king in the British Isles and they left the stadtholdership vacant for the second time. As William III died childless in 1702 the principality became a matter of dispute between Prince

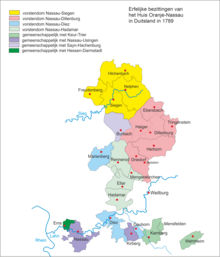

Hereditary territories in Germany

After the Nassau-Dietz branch took over, the House of Orange-Nassau had acquired the following territories by the end of the 18th century in the Holy Roman Empire, located in present-day Germany:[citation needed]

- County of Nassau-Dillenburg, elevated to principality in 1654

- County of Nassau-Siegen, elevated to principality

- County of Nassau-Dietz, elevated to principality

- County of Nassau-Hadamar, elevated to principality

- Fief Beilstein

- Fief Spiegelberg

- Nassau-Usingen)

- Amt Kirrberg (shared with Nassau-Usingen)

- Grund Seel and Burbach (shared with Nassau-Weilburg)

- Amt Camberg (shared with the Electorate of Trier)

- Amt Wehrheim (shared with the Electorate of Trier)

- Ems custody (shared with Hesse-Darmstadt)

Around 1742, William IV of Orange established the Hochdeutsche Hofdepartement, an administrative centre located in The Hague inside the Dutch Republic, which looked after the family's possessions in Germany.[11]

End of the stadtholdership

William IV died in 1751, leaving his three-year-old son, William V, as the stadtholder. Since William V was still a minor, the regents reigned for him. He grew up to be an indecisive person, a character defect which would come to haunt William V his whole life. His marriage to Wilhelmina of Prussia relieved this defect to some degree. In 1787, Willem V survived an attempt to depose him by the Patriots (anti-Orangist revolutionaries) after the Kingdom of Prussia intervened. When the French invaded Holland in 1795, William V was forced into exile, and he was never to return alive to Holland.[1]: 228–229 [3]: vol5, 289

After 1795, the House of Orange-Nassau faced a difficult period, surviving in exile at other European courts, especially those of Prussia and Britain. Following the recognition of the

Monarchy since 1813

| Dutch royalty House of Orange-Nassau |

|---|

|

| King William I |

| King William II |

| King William III |

| Queen Wilhelmina |

| Queen Juliana |

| Queen Beatrix |

| King Willem-Alexander |

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

After a repressed Dutch rebel action, Prussian and Cossack troops drove out the French in 1813, with the support of the Patriots of 1785. A provisional government was formed, most of whose members had helped drive out William V 18 years earlier. However, they were realistic enough to accept that any new government would have to be headed by William V's son, William Frederick (William VI). All agreed that it would be better in the long term for the Dutch to restore William themselves rather than have him imposed by the allies.[1]: 230

At the invitation of the provisional government, William Frederick returned to the Netherlands on November 30. This move was strongly supported by the United Kingdom, which sought ways to strengthen the Netherlands and deny future French aggressors easy access to the Low Countries' Channel ports. The provisional government offered William the crown. He refused, believing that a stadholdership would give him more power. Thus, on December 6, William proclaimed himself hereditary sovereign prince of the Netherlands—something between a kingship and a stadholdership. In 1814, he was awarded sovereignty over the Austrian Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège as well. On March 15, 1815, with the support of the powers gathered at the Congress of Vienna, William proclaimed himself King William I. He was also made grand duke of Luxembourg, and (to assuage French sensitivity by distancing the title from the now-defunct principality) the title 'Prince of Orange' was changed to 'Prince of Oranje'.[14] The two countries remained separate, though they shared a common monarch via a personal union. William had thus fulfilled the House of Orange's three-century quest to unite the Low Countries.[3]: vol5, 398

The institution of the monarch in the Netherlands is considered an office under the Constitution of the Netherlands.[15] There are none of the religious connotations to the office as in some other monarchies.[citation needed] A Dutch sovereign is inaugurated rather than crowned in a coronation ceremony.[citation needed] It was initially more of a crowned/hereditary presidency, and a continuation of the status quo ante of the pre-1795 hereditary stadholderate in the Republic.[citation needed] In practice, the current monarch has considerably less power than the stadtholder.[citation needed]

As king of the

The Prince of Orange held rights to Nassau lands (Dillenburg, Dietz, Beilstein, Hadamar, Siegen) in central Germany. On the other hand, the King of Prussia,

In 1830, most of the southern portion of William's realm—the former Austrian Netherlands and Prince-Bishopric—declared independence as Belgium. William fought a disastrous war until 1839 when he was forced to settle for peace. With his realm halved, he decided to abdicate in 1840 in favour of his son, William II. Although William II shared his father's conservative inclinations, in 1848 he accepted an amended constitution that significantly curbed his own authority and transferred the real power to the States General. He took this step to prevent the Revolutions of 1848 from spreading to his country.[3]: vol5, 455–463

William III and the risk of extinction

William II died in 1849. He was succeeded by his son, William III. A rather conservative, even reactionary man, William III was sharply opposed to the new 1848 constitution. He continually tried to form governments that were dependent on his support, even though it was prohibitively difficult for a government to stay in office against the will of Parliament. In 1868, he tried to sell Luxembourg to France, which was the source of a quarrel between Prussia and France.[3]: vol5, 483

William III had a rather unhappy marriage with

Monarchy in modern times

Wilhelmina was queen of the

The Netherlands remained neutral in World War I, during her reign, and the country was not invaded by Germany, as neighbouring Belgium was.[18]

Nevertheless, Queen Wilhelmina became a symbol of the Dutch resistance during World War II. The moral authority of the Monarchy was restored because of her rule. After 58 years on the throne as the Queen, Wilhelmina decided to abdicate in favour of her daughter, Juliana. Juliana had the reputation of making the monarchy less "aloof", and under her reign the Monarchy became known as the "cycling monarchy". Members of the royal family were often seen riding bicycles through the cities and the countryside under Juliana.[18]

A royal marriage controversy occurred in 1966 when Juliana's eldest daughter, the future Queen Beatrix, decided to marry Claus von Amsberg, a German diplomat. The marriage of a member of the royal family to a German was quite controversial in the Netherlands, which had suffered under Nazi German occupation in 1940–45. This reluctance to accept a German consort probably was exacerbated by von Amsberg's former membership in the Hitler Youth under the Nazi regime in his native country, and also his following service in the German Wehrmacht. Beatrix needed permission from the government to marry anyone if she wanted to remain heiress to the throne, but after some argument, it was granted. As the years went by, Prince Claus was fully accepted by the Dutch people. In time, he became one of the most popular members of the Dutch monarchy, and his death in 2002 was widely mourned.[18]

On April 30, 1980, Queen Juliana abdicated in favour of her daughter, Beatrix. In the early years of the twenty-first century, the Dutch monarchy remained popular with a large part of the population. Beatrix's eldest son,

Upon Beatrix's abdication on April 30, 2013, the Prince of Orange was inaugurated as King Willem-Alexander, becoming the Netherlands' first male ruler since 1890. His eldest daughter, Catharina-Amalia, as heiress apparent to the throne, became

Net worth

Unlike other royal houses, there has always been a separation in the Netherlands between what was owned by the state and used by the House of Orange in their offices as monarch, or previously, stadtholder, and the personal investments and fortune of the House of Orange.[citation needed]

As monarch, the King or Queen has use of, but not ownership of, the Huis ten Bosch as a residence and Noordeinde Palace as a work palace. In addition, the Royal Palace of Amsterdam is also at the disposal of the monarch (although it is only used for state visits and is open to the public when not in use for that purpose). Soestdijk Palace was sold to private investors in 2017. The

The House of Orange has long had the reputation of being one of the wealthier royal houses in the world, largely due to their business investments in

As late as 2001, the fortune of the Royal Family was estimated by various sources (Forbes magazine) at $3.2 billion. Most of the wealth was reported to come from the family's longstanding stake in the

The royal family's fortune seems to have been hit by declines in real estate and equities after 2008. They were also rumored to have lost up to $100 million when

List of rulers

Stadtholderate under the House of Orange-Nassau

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

John William Friso | Orange-Nassau |  | ||||

William V

| 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806 (aged 58) | 22 October 1751 | 9 April 1806 | Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands, son of William IV, succeeded by his son King William I (-> Principality of the Netherlands (1813–1815) | Orange-Nassau |  |

Stadtholderate under the Houses of Nassau-Dillenburg and Nassau-Dietz

Note:[35]

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

John William Friso | 4 August 1687 – 14 July 1711 (aged 23) | 25 March 1696 | 14 July 1711 | Hereditary Stadtholder,[42] son of Henry Casimir II, succeeded by his son William IV of Orange-Nassau, Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands (-> Stadtholderate under the House of Orange-Nassau | Nassau-Dietz, Orange-Nassau |  |

Principality of the Netherlands (1813–1815)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I | 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843 (aged 71) | 6 December 1813 | 16 March 1815 | Raised Netherlands to status of kingdom in 1815, son of Stadtholder William V | Orange-Nassau |  |

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–present)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I | 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843 (aged 71) | 16 March 1815 | 7 October 1840 | Son of the last Stadtholder William V | Orange-Nassau |  |

| William II | 6 December 1792 – 17 March 1849 (aged 56) | 7 October 1840 | 17 March 1849 | Son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

| William III | 17 February 1817 – 23 November 1890 (aged 73) | 17 March 1849 | 23 November 1890 | Son of William II | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Wilhelmina | 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962 (aged 82) | 23 November 1890 | 4 September 1948 | Daughter of William III | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Juliana | 30 April 1909 – 20 March 2004 (aged 94) | 4 September 1948 | 30 April 1980 | Daughter of Wilhelmina | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Beatrix | 31 January 1938 | 30 April 1980 | 30 April 2013 | Daughter of Juliana | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Willem-Alexander | 27 April 1967 | 30 April 2013 | Son of Beatrix | Orange-Nassau |  |

Royal family versus royal house

| Dutch royal family |

|

|

| * Member of the Dutch royal house |

Under Dutch law, there is a distinction between the royal family and the Dutch royal house. Whereas 'royal family' refers to the entire Orange-Nassau family, only a small subgroup of it constitutes the royal house. By the Royal House Membership Act 2002, membership of the royal house is limited to:[18][43]

The royal house and family is the Orange-Nassau family. [44]

- (Article 1) the reigning monarch (King or Queen);[43]

- (Article 1a) the members of the royal family in the line of succession to the Dutch throne, limited to the second degree of sanguinity reckoned from the reigning monarch;[43]

- (Article 1b) the heir presumptive of the reigning monarch;[43]

- (Article 1c) the former monarch (upon abdication);[43]

- (Article 2) the spouses of the above, even if the above die.[43]

- (Article 3) H.R.H. Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, (for whom an exception was made);[citation needed]

Members of the Royal House lose their membership (and thereby, designation as prince or princess of the Netherlands) if they lose the membership of the Royal House on the succession of a new monarch (not being in the second degree of sanguinity to the monarch anymore, Article 1a), or by royal decree approved by the Council of State (Article 5).[43] This last scenario could happen, for example, if a royal house member marries without the consent of the Dutch Parliament.[citation needed] For example, this happened with Prince Friso in 2004, when he married Mabel Wisse Smit.[citation needed]

Family tree

Origins of the Nassaus

The lineage of the House of Nassau can be traced back to the 10th century.

| Family tree of the House of Nassau | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The following family tree is compiled from Wikipedia and the reference cited in the note[45]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A detailed family tree can be found here.

Orange and Nassau Family Tree

| A summary family tree of the House of Orange-Nassau[48] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

From the joining of the Marshal de Turenne .

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The main house of Orange-Nassau also spawned several illegitimate branches. These branches contributed to the political and economic history of England and the Netherlands.

Royal House of Orange-Nassau

In 1815, William VI of Orange became King of the Netherlands. This summary genealogical tree shows how the current Royal house of Orange-Nassau is related:[18]

Coats of Arms

The gallery below show the

The ancestral coat of arms of the Ottonian line of the

Henry III of Nassau-Breda came to the Netherlands in 1499 as heir to his uncle,

-

Arms of Engelbrecht II and Henry III of Nassau-Breda.[52]

-

Coat of arms of Rene of Chalons as Prince of Orange.[52]

-

Arms of William the Rich, count of Nassau-Dillenburg.[52]

The princes of Orange in the 16th and 17th century used the following sets of arms. On becoming prince of Orange, William placed the Châlon-Arlay arms in the center ("as an inescutcheon") of his father's arms. He used these arms until 1582 when he purchased the

-

Coat of arms of William the Silent as Prince of Orange from 1544 to 1582, and his eldest son Philip William[52]

-

The coat of arms used by

-

An alternate coat of arms sometimes used byVeere.[55]

-

Coat of arms on expeditionary banner of William and Mary, 1688, showing the arms of William III impaled with the royal arms of England

-

Coat of arms of King William III of England as King of England.

When

-

Arms of Johan Willem Friso as Prince of Orange.[57]

-

Arms of William VI of Orange as prince of Orange-Nassau-Fulda. The bottom most shield shows clockwise from top left the principality of Fulda, the lordship of Corvey, the county of Weingarten, and the lordship of Dortmund.[56]

-

Arms of theMaurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, and his descendants the lords of den Lek and the earls of Grantham in England[56]

-

Arms of the lords of Zuylestein, natural son of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and his descendants the earls of Rochford in England[56]

When William VI of Orange returned to the Netherlands in 1813 and was proclaimed Sovereign Prince of the Netherlands, he quartered the former Arms of the Dutch Republic (1st and 4th quarter) with the "Châlon-Orange" arms (2nd and 3rd quarter), which had come to symbolize Orange. As an in escutcheon he placed his ancestral arms of Nassau. When he became King in 1815, he combined the Dutch Republic Lion with the billets of the Nassau arms and added a royal crown to form the Coat of arms of the Netherlands. In 1907, Queen Wilhelmina replaced the royal crown on the lion and the shield bearers of the arms with a coronet.[58]

-

Arms of the States General of the Dutch Republic. The sword symbolizes the determination to defend the nation, and the bundle of 7 arrows the unity of the 7 United Provinces of the Dutch Republic.

-

Arms of William VI as sovereign prince of the Netherlands.[52]

-

First arms of the Kingdom and Kings of the Netherlands from 1815 to 1907.[18]

Wilhelmina further decreed that in perpetuity her descendants should be styled "princes and princesses of Orange-Nassau" and that the name of the house would be "Orange-Nassau" (in Dutch "Oranje-Nassau"). Only those members of the members of the Dutch Royal Family that are designated to the smaller "Royal House" can use the title of prince or princess of the Netherlands.[18] Since then, individual members of the House of Orange-Nassau are also given their own arms by the reigning monarch, similar to the United Kingdom. This is usually the royal arms, quartered with the arms of the principality of Orange, and an in escutcheon of their paternal arms.[59]

-

Juliana of the Netherlands & Oranje-Nassau Personal Arms

-

Beatrix of the Netherlands & Oranje-Nassau Personal Arms

-

William Alexander of the Netherlands and Oranje-Nassau Personal Arms

-

Arms for children of King William Alexander of the Netherlands

-

Sons of Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, Pieter van Vollenhoven[60]

As sovereign Princes, the princes of Orange used an independent prince's crown or the princely hat. Sometimes, only the coronet part was used (see, here and here). After the establishment of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and as the principality of Orange had been incorporated into France by Louis XIV, they used the Dutch Royal Crowns. The full coats of arms of the princes of Orange, later Kings of the Netherlands, incorporated the arms above, the crown, 2 lions as supporters and the motto "Je maintiendrai" ("I will maintain"), the latter taken from the Chalons princes of Orange, who used "Je maintiendrai Chalons".[2]: 35

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Coat of Arms of Frederick Henry, William II and William III as sovereign princes of Orange.[52]

|

Royal coat of arms of the Netherlands (1815–1907)[18]

|

Royal coat of arms of the Netherlands (1907–present)[18]

|

Lands and titles

Titles

Besides being

- Marquis of Veere and Vlissingen

Dietz ![]() ,

Vianden

,

Vianden ![]() ,

Buren

,

Buren ![]() ,

Moers

,

Moers ![]() ,

Leerdam

,

Leerdam ![]() , and

Culemborg (1748)

, and

Culemborg (1748) ![]()

Cranendonck ![]() ,

Lands of Cuijk

,

Lands of Cuijk ![]() ,

Eindhoven

,

Eindhoven ![]() ,

City of Grave

,

City of Grave ![]() ,

Lek

,

Lek ![]() ,

IJsselstein

,

IJsselstein ![]() ,

Acquoy

,

Acquoy ![]() ,

Diest

,

Diest ![]() ,

Grimbergen

,

Grimbergen ![]() /

/![]() ,

Herstal

,

Herstal ![]() ,

Warneton (Waasten (nl))

,

Warneton (Waasten (nl)) ![]() ,

Beilstein

,

Beilstein ![]() ,

Bentheim-Lingen

,

Bentheim-Lingen ![]() ,

Arlay

,

Arlay ![]()

![]() ,

Nozeroy

,

Nozeroy ![]() , and

Orpierre

, and

Orpierre ![]() ;

;

- ,

Bredevoort ![]() ,

Dasburg

,

Dasburg ![]() ,

Geertruidenberg

,

Geertruidenberg![]() ,

Hooge en Lage Zwaluwe

,

Hooge en Lage Zwaluwe ![]() ,

Klundert

,

Klundert![]() ,

,

A fuller listing with maps of the territories are in the Maps of the Lands of the House of Orange.

Standards

The Dutch Royal Family also makes extensive use of royal standards that are based on their coats of arms, but not identical to them (as the British Royal Family does). Some examples from the Royal Family's website are:[18]

The standards of the ruling king or queen:

-

Royal Flag of the Netherlands (1815–1908)

-

Royal Standard of Wilhelmina, Juliana and Beatrix (1908–2013)

-

Royal Standard of the King

The standards of the current sons of the former Queen, now Princess Beatrix and their wives and the Queen's husband:

-

Royal Standard of the Princes of the Netherlands (Sons of Queen Beatrix)

-

Standard of Claus von Amsberg as Royal consort of the Netherlands

-

Standard of Princess Maxima of the Netherlands

-

Standard of Princess Laurentien of the Netherlands

A fuller listing can be found at the Armorial de la Maison de Nassau, section Lignée Ottonienne at the French Wikipedia.

Residences of the House of Orange

-

Hotel de Nassau in Brussels painted 1658 (former residence)

-

Royal Palace of Amsterdam (official ceremonial residence)

-

Noordeinde Palace, The Hague (working offices of the Monarch)

-

Huis ten Bosch palace, The Hague

-

Schloss Oranienstein (former residence)

See also

For further about the Dutch Monarchy and the Dutch Royal House:

- Dutch monarchy

- House of Nassau

- Prince of Orange

- Principality of Orange

- Orange Institution

- William III of England

Traditionally, members of the Nassau family were buried in

- Crypt of the House of Orange-Nassau (in Dutch) in Delft

- Burial Monument to William the Silent (in Dutch)

- Crypt of the Frisian Nassaus (in Dutch) in Leeuwarden

- Crypt of the Nassau-LaLecqs in Ouderkerk aan den IJssel (in Dutch)

- Original Crypt of Netherland Nassaus (in Dutch) in Breda

- Crypt of Engelbrecht II van Nassau (in Dutch) in Breda

- Crypt of the Nassau-Bergens in Bergen (in Dutch)

- Crypt of the Nassau-Siegens (in Dutch) in Siegen

In Robert A. Heinlein's 1956 science fiction novel Double Star, the House of Orange reigns over – but does not rule over – an empire of humanity that spans the entire Solar System.

Notes

- ^ In isolation, van is pronounced [vɑn].

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rowen, Herbert H. (1988). The princes of Orange: the stadholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d Grew, Marion Ethel (1947). The House of Orange. 36 Essex Street, Strand, London W.C.2: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Blok, Petrus Johannes (1898). History of the people of the Netherlands. New York: G. P. Putnam's sons.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-820734-4paperback.

- ^ Motley, John Lothrop (1855). The Rise of the Dutch Republic. Harper & Brothers.

- ^ a b Motley, John Lothrop (1860). History of the United Netherlands from the Death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort. London: John Murray.

- ^ a b c d Geyl, Pieter (2002). Orange and Stuart 1641–1672. Arnold Pomerans (trans.) (reprint ed.). Phoenix.

- ^ ISBN 9780691052472.

- ^ ISBN 0-15-518473-3.

- ^ Delff, Willem Jacobsz. "De Nassauische Cavalcade". From an engraving on exhibit in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ISBN 9783830979692. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ He acquired Fulda, Corvey, Weingarten and Dortmund. He lost the possessions again after changing sides from France to Prussia in 1806 when he refused to join the Confederation of the Rhine. Cf. J. and A. Romein 'Erflaters van onze beschaving', Querido, 1979

- S2CID 155502574.

- ^ Couvée, D.H.; G. Pikkemaat (1963). 1813-15, ons koninkrijk geboren. Alphen aan den Rijn: N. Samsom nv. pp. 119–139.

- ^ Articles 24–49 of the Constitution of the Netherlands.

- ^ "Were A Monarch To Fall Dead", The Washington Post, 7 May 1905.

- ^ a b J.g. Kikkert (30 April 1997). "Het beatrixisme: zolang Beatrix de PvdA aan haar zijde weet te houden, is er voor Oranje weinig kou in de lucht". De Groene Amsterdammer. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "The Official Website of the Dutch Royal House in English". Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Dutch Royal House – Movable Property". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ (in Dutch) Constitution for the Kingdom of the Netherlands Article 40 (Dutch edition of WikiSource)

- ^ Koninkrijksrelaties, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en (18 October 2012). "The Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 2008". www.government.nl.

- ^ a b "In Pictures: The World's Richest Royals." Forbes. 7 July 2010. 30 September 2010.

- ^ "How Much Is Queen Elizabeth Worth?." Forbes 26 June 2001.

- ^ "Royal Flush." Forbes 4 March 2002.

- ^ "Monarchs and the Madoff Scandal." Forbes. 17 June 2009.

- ^ "In Pictures: The World's Richest Royals". Forbes.com. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ "Report: The World's Richest Royals." Forbes. April 29, 2011.

- ^ Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht (employed by Philip II: 1559 – 1567, employed by the States General: 1572 – 1584), Stadtholder of Friesland and Overijssel (1580–1584)

- ^ Stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland (1585–1625), Utrecht, Guelders and Overijssel (1590–1625), Groningen (1620–1625)

- ^ Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel (1620–1625), Groningen and Drenthe (1640–1647)

- ^ Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Groningen, Drenthe and Overijssel

- ^ Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht and Overijssel (1672–1702), Guelders (1675–1702), Drenthe (1696–1702)

- ^ William III invaded – on invitation – England and became king of England, Scotland and Ireland

- ^ Hereditary Stadtholder of Friesland (1711–1747), Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht and Overijssel (April/May 1747 – November 1747), Stadtholder of Groningen (1718–1747), Guelders and Drenthe (1722–1747), was formally voted the first Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Provinces (1747–1751)

- ^ Stadtholders of Friesland, Groningen and Drenthe, became the direct male line ancestor of the Republic's hereditary Stadtholders, and later of the kings of the Netherlands.

- Guelders (under Philip II), architect of the Union of Utrecht

- ^ Stadtholder of Friesland (1584–1620), Groningen (1594–1620) and Drenthe (1596–1620)

- ^ Stadtholder of Friesland (1620–1632), Groningen and Drenthe (1625–1632)

- ^ Stadtholder of Friesland (1632–1640), Groningen and Drenthe (1632–1640)

- ^ Stadtholder of Friesland (1640–1664), Groningen and Drenthe (1650–1664)

- ^ In 1675 the State of Friesland voted to make the Stadtholdership hereditary in the house of Nassau-Dietz

- ^ Hereditary Stadtholder of Friesland (1707–1711) and Griningen (1708–1711)

- ^ a b c d e f g "wetten.nl – Regeling – Wet lidmaatschap koninklijk huis – BWBR0013729". wetten.overheid.nl.

- ^ "The Official Website of the Dutch Royal House in English". Retrieved 9 January 2024.

The Royal House of the Netherlands is the House of Orange-Nassau.

- ^ Louda, Jiri; Maclagan, Michael (December 12, 1988), "Netherlands and Luxembourg, Table 33", Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe (1st (U.S.) ed.), Clarkson N. Potter, Inc.

- ^ Marek, Miroslav. "Nassau index page". genealogy.euweb.cz. Retrieved 5 September 2013.[self-published source]

- ISBN 1-85605-469-1.

- ^ "Official Website of the Dutch Royal House". Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst (RVD), The Hague, the Netherlands. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Rietstap, Johannes Baptist (1875). Handboek der Wapenkunde. the Netherlands: Theod. Bom. p. 348.

Prins FREDERIK: Het koninklijke wapen, in 't shcildhoofd gebroken door een rooden barensteel, de middelste hanger beladen met een regtopstaanden goud pijl.

- ^ Junius, J.H. (1894). Heraldiek. the Netherlands: Frederik Muller. p. 151.

...de tweede oon voert het koninklijk wapen gebroken door een barensteel van drie stukken met een zilveren pijl.

- ^ Junius, J.H. (1894). Heraldiek. the Netherlands: Frederik Muller. p. 151.

...is het wapen afgebeeld van de oudste dochter van den Koning der Nederlanden. De barensteel is van keel en beladen met een gouden koningskroon.

- ^ ISBN 0-8063-4811-9. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

Ecartelé : au 1. d'azur, semé de billettes d'or au lion d'or, armé et lampassé de gueules, brochant sur le tout (Maison de Nassau); II, d'or, au léopard lionné de gueules, arméc ouronné et lampassé d'azur (Katzenelnbogen); III, de gueules à la fasce d'argent (Vianden); IV, de gueules à deux lions passant l'un sur l'autre; sur-le-tout écartelé, aux I et IV de gueules, à la bande d'or (Châlon), et aux II et III d'or, au cor de chasse d'azur, virolé et lié de gueules (Orange); sur-le-tout-du-tout de cinq points d'or équipolés à quatre d'azur (Genève); un écusson de sable à la fasce d'argent brochant en chef (Marquis de Flessingue et Veere); un écusson de gueules à la fasce bretessée et contre-bretessée d'argent brochant en pointe (Buren). Cimier: 1er un demi-vol cont. coupé d'or sur gueles (Chalons), 2er une ramure de cerf d'or (Orange) 3er un demi-vol de sa, ch. d'un disque de armes de Dietz. Supports: deux lions d'or, arm. et lamp. de gueles. Devise: JE MAINTIENDRAI.

- ^ Anonymous. "Wapenbord van Prins Maurits met het devies van de Engelse orde van de Kouseband". Exhibit of a painted woodcut of Maurice's Arms encircled by the Order of the Garter in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Rietstap, Johannes Baptist (1861). Armorial général, contenant la description des armoiries des familles nobles et patriciennes de l'Europe: précédé d'un dictionnaire des termes du blason. G.B. van Goor. p. 746.

a la exception de celebre prince Maurice qui portai les armes ...

- ^ Post, Pieter (1651). "Coat of Arms as depicted in "Begraeffenisse van syne hoogheyt Frederick Hendrick"". engraving, in the collection of. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Rietstap, Johannes Baptist (1861). Armorial général, contenant la description des armoiries des familles nobles et patriciennes de l'Europe: précédé d'un dictionnaire des termes du blason. G.B. van Goor. p. 746.

- ^ ""Coat of Arms as depicted on the "Familiegraf van de Oranje-Nassau's in de Grote of Jacobijnerkerk te Leeuwarden"". Familiegraf van de Oranje-Nassau's in de Grote of Jacobijnerkerk te Leeuwarden. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Wapens van leden van het Koninklijk Huis". Coats of Arms of the Dutch Royal Family, Website of the Dutch Monarchy, the Hague. Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst (RVD), the Hague, the Netherlands. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

Het wapen van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden (Rijkswapen) en dat van de Koningen der Nederlanden (Koninklijk wapen) is vanaf de oprichting van het Koninkrijk in 1815 identiek. Het Wapen werd in 1907 gewijzigd en laatstelijk vastgesteld bij Koninklijk Besluit van 23 april 1980, nr. 3 (stb. 206) bij de troonsaanvaarding van Koningin Beatrix. De beschrijving van het wapenschild in het eerste artikel is dwingend voorgeschreven, de in het tweede en derde artikel beschreven uitwendige versierselen zijn facultatief. In de praktijk wordt de basisuitvoering van het wapen wel het Klein Rijkswapen genoemd. Het Koninklijk Wapen wordt sinds 1907 gekenmerkt door een gouden klimmende leeuw met gravenkroon. De blauwe achtergrond (het veld) is bezaaid met verticale gouden blokjes. De term bezaaid geeft in de heraldiek aan dat het aantal niet vaststaat, waardoor er ook een aantal niet compleet zijn afgebeeld. Het wapenschild wordt gehouden door twee leeuwen die in profiel zijn afgebeeld. Op het wapenschild is een Koningskroon geplaatst. Op een lint dat onder het wapenschild bevestigd is, staat de spreuk 'Je Maintiendrai'. Bij Koninklijk Besluit van 10 juli 1907 (Stb. 181) werd het Koninklijk Wapen, tevens Rijkswapen, aangepast. De leeuw in het schild en de schildhoudende leeuwen droegen vóór die tijd alle drie de Koninklijke kroon, maar raakten deze kwijt nu de toegevoegde purperen hermelijn gevoerde mantel, gedekt door een purperen baldakijn, een Koningskroon ging dragen. De schildhouders waren vóór 1907 bovendien aanziend in plaats van en profiel.

- ^ "Wapens van leden van het Koninklijk Huis". Coats of Arms of the Dutch Royal Family, Website of the Dutch Monarchy, the Hague. Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst (RVD), the Hague, the Netherlands. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Klaas. "Maurits van Vollenhoven". Article on Maurits van Vollenhoven, 18-09-2008 10:28. klaas.punt.nl. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ISBN 90-73714-18-4.

Cited works

- Herbert H. Rowen, The princes of Orange: the stadholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- John Lothrop Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855.

- John Lothrop Motley, History of the United Netherlands from the Death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort. London: John Murray, 1860.

- Petrus Johannes Blok, History of the people of the Netherlands. New York: G. P. Putnam's sons, 1898.

- ISBN 0-19-820734-4

- Pieter Geyl, Orange and Stuart 1641–1672. Phoenix Press, 2002.

- Mark Edward Hay, "Russia, Britain, and the House of Nassau: The Re-Establishment of the Orange Dynasty in the Netherlands, March–November 1813" Archived 2018-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, Low Countries Historical Review 133/1, March 2018, 3–21.

Further reading

- Edmundson, George (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). p. 146.

- John Lothrop Motley, The Life and Death of John of Barenvelt. New York & London: Harper and Brothers Publishing, 1900.

- Rouven Pons (Hrsg.): Oranien und Nassau in Europa. Lebenswelten einer frühneuzeitlichen Dynastie. ISBN 978-3-930221-38-7.

!["The Nassau Cavalcade", members of the House of Orange-Nassau on parade in 1621 from an engraving by Willem Delff. From left to right in the first row: Prince Maurice, Prince Philip William and Prince Frederick Henry, between Maurice and Frederick Henry is William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg.[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Willem_Jacobsz._Delff_003.jpg/120px-Willem_Jacobsz._Delff_003.jpg)

![Arms of Engelbrecht II and Henry III of Nassau-Breda.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a4/Nassau-Dillenburg_1420_klein.svg/102px-Nassau-Dillenburg_1420_klein.svg.png)

![Coat of arms of Rene of Chalons as Prince of Orange.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/Nassau-Chalons_wapen.svg/107px-Nassau-Chalons_wapen.svg.png)

![Arms of William the Rich, count of Nassau-Dillenburg.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Nassau-Dillenburg_1559-1739.svg/102px-Nassau-Dillenburg_1559-1739.svg.png)

![Coat of arms of William the Silent as Prince of Orange from 1544 to 1582, and his eldest son Philip William[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Willem_van_Oranje_wapen_oud.svg/102px-Willem_van_Oranje_wapen_oud.svg.png)

![The coat of arms used by William the Silent from 1582 until his death, Frederick Henry, William II, and William III as Prince of Orange[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Arms_of_William_Henry%2C_Prince_of_Orange%2C_Count_of_Nassau_with_Veere.svg/98px-Arms_of_William_Henry%2C_Prince_of_Orange%2C_Count_of_Nassau_with_Veere.svg.png)

![An alternate coat of arms sometimes used by Frederick Henry, William II, and William III as Prince of Orange showing the county of Moers in the top center rather than Veere.[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Arms_of_William_Henry%2C_Prince_of_Orange%2C_Count_of_Nassau.svg/98px-Arms_of_William_Henry%2C_Prince_of_Orange%2C_Count_of_Nassau.svg.png)

![Arms of Johan Willem Friso as Prince of Orange.[57]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Arms_of_Johan_Willem_Friso_as_Prince_of_Orange.JPG/105px-Arms_of_Johan_Willem_Friso_as_Prince_of_Orange.JPG)

![Arms of William VI of Orange as prince of Orange-Nassau-Fulda. The bottom most shield shows clockwise from top left the principality of Fulda, the lordship of Corvey, the county of Weingarten, and the lordship of Dortmund.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/Nassau-Fulda_wapen.svg/103px-Nassau-Fulda_wapen.svg.png)

![Arms of Justinus van Nassau,[56] natural son of William the Silent.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Justinus_van_Nassau_wapen.svg/102px-Justinus_van_Nassau_wapen.svg.png)

![Arms of the Louis of Nassau, Lord of De Lek and Beverweerd, natural son of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, and his descendants the lords of den Lek and the earls of Grantham in England[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Nassau_laLecq.svg/102px-Nassau_laLecq.svg.png)

![Arms of the lords of Zuylestein, natural son of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and his descendants the earls of Rochford in England[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/Blason_Nassau-Zuylestein.svg/109px-Blason_Nassau-Zuylestein.svg.png)

![Arms of William VI as sovereign prince of the Netherlands.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Arms_of_Sovereign_Prince_William_I_of_Orange.svg/98px-Arms_of_Sovereign_Prince_William_I_of_Orange.svg.png)

![First arms of the Kingdom and Kings of the Netherlands from 1815 to 1907.[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Royal_Arms_of_the_Netherlands_%281815-1907%29.svg/111px-Royal_Arms_of_the_Netherlands_%281815-1907%29.svg.png)

![Arms of the Kingdom and Kings of the Netherlands since 1907.[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/40/Arms_of_the_Kingdom_of_the_Netherlands.svg/98px-Arms_of_the_Kingdom_of_the_Netherlands.svg.png)

![Sons of Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, Pieter van Vollenhoven[60]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/Arms_of_the_children_of_Margriet_of_the_Netherlands.svg/98px-Arms_of_the_children_of_Margriet_of_the_Netherlands.svg.png)