Hubert Wilkins

Sir Hubert Wilkins | |

|---|---|

Sir Hubert Wilkins (1931) | |

| Born | 31 October 1888 |

| Died | 30 November 1958 (aged 70) |

| Known for | Polar explorer |

| Spouse | Suzanne Bennett |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor Military Cross & Bar |

Sir George Hubert Wilkins

Early life

Hubert Wilkins was a native of

World War I

In 1917, Wilkins returned to his native Australia, joining the

Wilkins' work frequently led him into the thick of the fighting and during the

When Australian WWI general Sir John Monash was asked by the visiting American journalist Lowell Thomas (who had written With Lawrence in Arabia and made T. E. Lawrence an international hero) if Australia had a similar hero, Monash spoke of Wilkins: "Yes, there was one. He was a highly accomplished and absolutely fearless combat photographer. What happened to him is a story of epic proportions. Wounded many times ... he always came through. At times he brought in the wounded, at other times he supplied vital intelligence of enemy activity he observed. At one point he even rallied troops as a combat officer ... His record was unique."[7]

Early career and personal life

After the war, Wilkins served in 1921–22 as an

Wilkins in 1923 began a two-year study for the British Museum of the bird life of Northern Australia. This ornithology project occupied his life until 1925.[4] His work was greatly acclaimed by the museum but derided by Australian authorities because of the sympathetic treatment afforded to Indigenous Australians and criticisms of the ongoing environmental damage in the country.

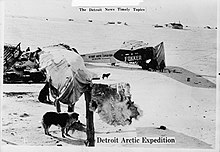

In March 1927, Wilkins and pilot Carl Ben Eielson explored the drift ice north of Alaska, touching down upon it in Eielson's airplane in the first land-plane descent onto drift ice. Soundings taken at the landing site indicated a water depth of 16,000 feet, and Wilkins hypothesized from the experience that future Arctic expeditions would take advantage of the wide expanses of open ice to use aircraft in exploration.[8] In December 1928, Wilkins and Eielson took off from Deception Island, one of Antarctic's most remote islands, and made the first successful airplane flight over the continent.[9]

Wilkins was the first recipient of the

On 15 April 1928, a year after

Now financed by

Wilkins was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1930.[13]

Nautilus expedition

Preparations

In 1930 Wilkins and his wife, Suzanne, were vacationing with a wealthy friend and colleague Lincoln Ellsworth. During this outing Wilkins and Ellsworth hammered out plans for a trans-Arctic expedition involving a submarine. Wilkins said the expedition was meant to conduct a "comprehensive meteorology study" and collect "data of academic and economic interest". He also anticipated Arctic weather stations and the potential to forecast Arctic weather "several years in advance". Wilkins believed a submarine could take a fully equipped laboratory into the Arctic.[14]

Ellsworth contributed $70,000, plus a $20,000 loan. Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst purchased exclusive rights to the story for $61,000. The

Wilkins described the planned expedition in his 1931 book Under The North Pole, which Wonder Stories praised as "[as] exciting as it is epochal".[17]

Expedition

The expedition suffered losses before they even left New York Harbor. Quartermaster Willard Grimmer was knocked overboard and drowned in the harbor.[18]

Wilkins was undaunted and drove on with preparations for a series of test cruises and dives before they were to undertake their trans-Arctic voyage.[19] Wilkins and his crew made their way up the Hudson River to Yonkers, eventually reaching New London, Connecticut, where additional modifications and test dives were performed. Satisfied with the performance of both the machinery and the crew, Wilkins and his men left the relative safety of coastal waterways for the uncertainty of the North Atlantic on 4 June 1931.

Soon after the commencement of the expedition the starboard engine broke down, and soon after that the port engine followed suit. On 14 June 1931 without a means of propulsion Wilkins was forced to send out an SOS and was rescued later that day by the USS Wyoming.[20] The Nautilus was towed to Ireland on 22 June 1931, and was taken to England for repairs.

On 28 June the Nautilus was up and running and on her way to Norway to pick up the scientific contingent of their crew. By 23 August they had left Norway and were only 600 miles from the North Pole. It was at this time that Wilkins uncovered another setback. His submarine was missing its diving planes. Without diving planes he would be unable to control the Nautilus while submerged.

Wilkins was determined to do what he could without the diving planes. For the most part Wilkins was thwarted from discovery under the ice floes.[20] The crew was able to take core samples of the ice, as well as testing the salinity of the water and gravity near the pole.[21]

Wilkins had to acknowledge that his adventure into the Arctic was becoming too foolhardy when he received a wireless plea from Hearst which said, "I most urgently beg of you to return promptly to safety and to defer any further adventure to a more favorable time, and with a better boat."[22]

Wilkins ended the first expedition to the poles in a submarine and headed for England, but was forced to take refuge in the

Despite the failure to meet his intended objective, he was able to prove that submarines were capable of operating beneath the polar ice cap, thereby paving the way for future successful missions.

Later life and career

Wilkins became a student of The Urantia Book and supporter of the Urantia movement after joining the '70' group in Chicago in 1942. After the book's publication in 1955, he 'carried the massive work on his long travels, even to the Antarctic' and told associates that it was his religion.[24]

On 16 March 1958, Wilkins appeared as a guest on the TV panel show What's My Line?[25]

Death and legacy

Wilkins died in Framingham, Massachusetts, on 30 November 1958. The US Navy later took his ashes to the North Pole aboard the submarine USS Skate on 17 March 1959. The Navy confirmed on 27 March that, "In a solemn memorial ceremony conducted by Skate shortly after surfacing, the ashes of Sir Hubert Wilkins were scattered at the North Pole in accordance with his last wishes."[26]

The

A species of Australian skink, Lerista wilkinsi, is named after him,[27]

as is a species of rock wallaby,

He is briefly portrayed by actor John Dease in the film Smithy (1946).

Works

- 1917 "Report on topographical and geographical work". Canadian Arctic Expedition. Ottawa: J. de Labroquerie Taché. 1917.

- 1928 Flying the Arctic. Grosset & Dunlap. 1928.

- 1928 Undiscovered Australia. Putnam. 1998. ISBN 9780859052450.

- 1931 Under The North Pole. Brewer, Warren & Putnam. 1931.

- 1942 with Harold M. Sherman: Thoughts Through Space, Creative Age Press. Republished as Thoughts Through Space: A Remarkable Adventure in the Realm of Mind. Hampton Roads Publishing Co. 2004. ISBN 1-57174-314-6.

See also

- Thomas George Lanphier, Sr.

References

- ^ Howgego, Raymond (2004). Encyclopedia of Exploration (Part 2: 1800 to 1850). Potts Point, NSW, Australia: Hordern House.

- ^ "Distance Mount Bryan East – Adelaide". Tripstance.com. 2013–2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Capt. Wilkins". The Observer. 9 June 1928. p. 54. Retrieved 19 September 2016 – via Trove.

- ^ ISBN 1-55297-590-8.

- ^ ISSN 1833-7538.

- ^ "No. 31370". The London Gazette (Supplement). 3 June 1919. p. 6823.

- ^ Thomas (1961), pp. 1-2.

- ^ Althoff, William F. Drift Station: Arctic outposts of superpower science. Potomac Books Inc., Dulles, Virginia. 2007. p. 35.

- ^ "Antarctic Aerial Exploration".

- ^ "The Cullum Geographical Medal" Archived 4 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. American Geographical Society. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Wilkins, Hubert Wilkins. Flying the Arctic. p. 313.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Under the North Pole: the Voyage of the Nautilus, The Ohio State University Libraries". Library.osu.edu. 4 June 1931. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ Pigboats (retrieved 27 February 2018)

- ^ "Polar Sub Can Drill Through Ice", April 1931, Popular Science. April 1931. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "Book Reviews", Wonder Stories, July 1931, p.287

- ^ "The Arctic Dive, Under the North Pole: the Voyage of the Nautilus". Library.osu.edu. 23 August 1931. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ Fricke, Hans; Fricke, Sebastian (2011). "Frozen North – Sir Hubert's Forgotten Submarine Expedition". Fricke Productions. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Rediscovering the World's First Arctic Submarine: Nautilus 1931". Ussnautilus.org. 30 November 1931. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ Insertlibrary.osu.edu "Under the North Pole: The Voyage of the Nautilus, the Ohio State University Libraries". Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2010. footnote text here

- ^ "Science: Wilkins Through". Time. 14 September 1931. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008.

- ^ "The Nautilus Expedition". Amphilsoc.org. 20 November 1931. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ Nasht (2005), p. 278.

- ^ "What's My Line?: EPISODE #406". TV.com. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Atomic Sub Drills Holes in Polar Ice", Oakland Tribune, 17 March 1959, p1

- ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Wilkins", pp. 285-286).

- The Australian Museum. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

Further reading

- Thomas, Lowell (1961). Sir Hubert Wilkins: His World of Adventure. McGraw-Hill. OCLC 577082956.

- Nasht, Simon (2005). The Last Explorer: Hubert Wilkins Australia's Unknown Hero. Sydney, Australia: Hachette/Hodder & New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 0-7336-1831-6. Archived from the originalon 23 February 2009.

- Voyage of the Nautilus, Documentary 2006, AS Videomaker/Real Pictures

- Jenness, Stuart E (2006). The Making of an Explorer. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2798-2.

- Maynard, Jeff (2010). Wings of Ice: The Air Race to the Poles. Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74166-934-3.

- FitzSimons, Peter (2021). The Incredible Life of Hubert Wilkins: Australia's Greatest Explorer. Hachette Australia. ISBN 9780733641374.

External links

- Australian War Memorial Entry for Sir George Hubert Wilkins

- Register of The Sir George Hubert Wilkins Papers

- Sir Hubert Wilkins biography from Flinders Ranges Research

- In Search of Sir Hubert Short bio on Sir Hubert Wilkins

- Searching for Sir Hubert Documentary Filmmaker site

- The 1931 Nautilus Expedition to the North Pole

- The Last Explorer: Simon Nasht Life&Times radio documentary, first broadcast by ABC Radio National, 29 August 2009

- Newspaper clippings about Hubert Wilkins in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- The Papers of George Hubert Wilkins at Dartmouth College Library