Human leg

| Human leg | |

|---|---|

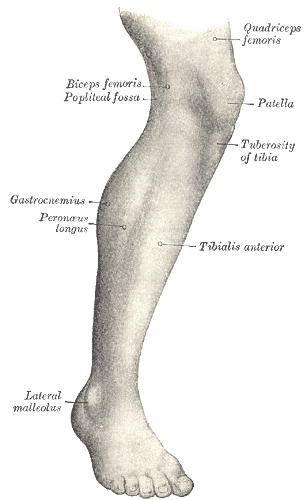

Lateral aspect of right leg | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrum inferius |

| FMA | 7184 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

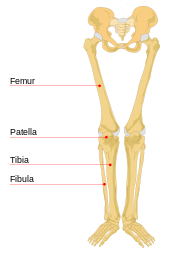

The leg is the entire lower limb of the human body, including the foot, thigh or sometimes even the hip or buttock region. The major bones of the leg are the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), and adjacent fibula. The thigh is between the hip and knee, while the calf (rear) and shin (front) are between the knee and foot.[1]

Legs are used for

Structure

In human anatomy, the lower leg is the part of the lower limb that lies between the knee and the ankle.[1] Anatomists restrict the term leg to this use, rather than to the entire lower limb.[5] The thigh is between the hip and knee and makes up the rest of the lower limb.[1] The term lower limb or lower extremity is commonly used to describe all of the leg.

The leg from the knee to the ankle is called the crus.

Evolution has provided the human body with two distinct features: the specialization of the upper limb for visually guided manipulation and the lower limb's development into a mechanism specifically adapted for efficient bipedal gait.[2] While the capacity to walk upright is not unique to humans, other primates can only achieve this for short periods and at a great expenditure of energy.[3]

The human adaption to bipedalism has also affected the location of the body's

Skeleton

The major

Usually, the large joints of the lower limb are aligned in a straight line, which represents the mechanical longitudinal axis of the leg, the

The angle of inclination formed between the neck and shaft of the femur (collodiaphysial angle) varies with age—about 150° in the newborn, it gradually decreases to 126–128° in adults, to reach 120° in old age. Pathological changes in this angle result in abnormal posture of the leg: a small angle produces coxa vara and a large angle coxa valga; the latter is usually combined with genu varum, and coxa vara leads genu valgum. Additionally, a line drawn through the femoral neck superimposed on a line drawn through the femoral condyles forms an angle, the torsion angle, which makes it possible for flexion movements of the hip joint to be transposed into rotary movements of the femoral head. Abnormally increased torsion angles result in a limb turned inward and a decreased angle in a limb turned outward; both cases resulting in a reduced range of a person's mobility.[12]

Muscles

Hip

| Movement | Muscles (in order of importance) |

|---|---|

| Lateral rotation |

•Sartorius |

| Medial rotation |

•Gluteus medius and |

| Extension |

•Gluteus maximus |

| Flexion |

•Iliopsoas |

| Abduction |

•Gluteus medius |

| Adduction |

•Adductor magnus |

| Notes | ♣ Also act on vertebral joints. * Also act on knee joint. |

There are several ways of classifying the muscles of the hip:

- By location or innervation (ventral and dorsal divisions of the plexus layer);

- By development on the basis of their points of insertion (a posterior group in two layers and an anterior group); and

- By function (i.e. extensors, flexors, adductors, and abductors).[14]

Some hip muscles also act either on the knee joint or on vertebral joints. Additionally, because the areas of origin and insertion of many of these muscles are very extensive, these muscles are often involved in several very different movements. In the hip joint, lateral and medial rotation occur along the axis of the limb; extension (also called dorsiflexion or retroversion) and flexion (anteflexion or anteversion) occur along a transverse axis; and abduction and adduction occur about a

The anterior dorsal hip muscles are the

The posterior dorsal hip muscles are inserted on or directly below the

The ventral hip muscles function as lateral rotators and play an important role in the control of the body's balance. Because they are stronger than the medial rotators, in the normal position of the leg, the apex of the foot is pointing outward to achieve better support. The

The

The

Thigh

| Movement | Muscles (in order of importance) |

|---|---|

| Extension |

•Quadriceps femoris |

| Flexion |

•Semimembranosus |

| Medial rotation |

•Semimembranosus |

| Lateral rotation |

•Biceps femoris |

| *Insignificant assistance. | |

The muscles of the thigh can be classified into three groups according to their location: anterior and posterior muscles and the adductors (on the medial side). All the adductors except gracilis insert on the femur and act on the hip joint, and so functionally qualify as hip muscles. The majority of the thigh muscles, the "true" thigh muscles, insert on the leg (either the tibia or the fibula) and act primarily on the knee joint. Generally, the extensors lie on anterior of the thigh and flexors lie on the posterior. Even though the sartorius flexes the knee, it is ontogenetically considered an extensor since its displacement is secondary.[14]

Of the anterior thigh muscles the largest are the four muscles of the

There are four posterior thigh muscles. The

Lower leg and foot

| Movement | Muscles (in order of importance) |

|---|---|

| Dorsi- flexion |

•Tibialis anterior |

| Plantar flexion |

•Triceps surae |

Eversion

|

•Fibularis (peroneus) longus |

| Inversion |

•Triceps surae |

With the

Dorsiflexion (extension) and plantar flexion occur around the transverse axis running through the ankle joint from the tip of the medial malleolus to the tip of the lateral malleolus. Pronation (eversion) and supination (inversion) occur along the oblique axis of the ankle joint.[25]

Extrinsic

Three of the anterior muscles are extensors. From its origin on the lateral surface of the tibia and the interosseus membrane, the three-sided belly of the

Of the posterior muscles three are in the superficial layer. The major plantar flexors, commonly referred to as the

In the deep layer, the

Intrinsic

The intrinsic muscles of the foot, muscles whose bellies are located in the foot proper, are either dorsal (top) or plantar (sole). On the dorsal side, two long extrinsic extensor muscles are superficial to the intrinsic muscles, and their tendons form the dorsal aponeurosis of the toes. The short intrinsic extensors and the plantar and dorsal interossei radiates into these aponeuroses. The extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis have a common origin on the anterior side of the calcaneus, from where their tendons extend into the dorsal aponeuroses of digits 1–4. They act to dorsiflex these digits.[32]

The plantar muscles can be subdivided into three groups associated with three regions: those of the big digit, the little digit, and the region between these two. All these muscles are covered by the thick and dense

The

The

The four

Flexibility

Flexibility can be simply defined as the available

Stretching

Stretching prior to strenuous physical activity has been thought to increase muscular performance by extending the soft tissue past its attainable length in order to increase range of motion.

- Plantar flexion: One of the most popular lower leg muscle stretches is the step standing ankle jointby raising the heel. This exercise is easily modified by holding on to a nearby rail for balance and is generally repeated 5–10 times.

- Dorsiflexion: In order to stretch the extensor digitorum longus, by slowly causing the muscles to lengthen as body weight is leaned on the ankle joint by using the floor as resistance against the top of the foot.[41] Crossover shin stretches can vary in intensity depending on the amount of body weight applied on the ankle joint as the individual bends at the knee. This stretch is typically held for 15–30 seconds.

- Eversion and inversion: Stretching the

Blood supply

The arteries of the leg are divided into a series of segments.

In the pelvis area, at the level of the last

The artery enters the thigh as the

In the lower leg, the anterior tibial enters the extensor compartment near the upper border of the

For practical reasons the lower limb is subdivided into somewhat arbitrary regions:[43] The regions of the hip are all located in the thigh: anteriorly, the subinguinal region is bounded by the inguinal ligament, the sartorius, and the pectineus and forms part of the femoral triangle which extends distally to the adductor longus. Posteriorly, the gluteal region corresponds to the gluteus maximus. The anterior region of the thigh extends distally from the femoral triangle to the region of the knee and laterally to the tensor fasciae latae. The posterior region ends distally before the popliteal fossa. The anterior and posterior regions of the knee extend from the proximal regions down to the level of the tuberosity of the tibia. In the lower leg the anterior and posterior regions extend down to the malleoli. Behind the malleoli are the lateral and medial retromalleolar regions and behind these is the region of the heel. Finally, the foot is subdivided into a dorsal region superiorly and a plantar region inferiorly.[43]

Veins

The

Superficial veins:

- Great saphenous vein

- Small saphenous

Deep veins:

- common femoral vein

- Popliteal vein

- Anterior tibial vein

- Posterior tibial vein

- Fibular vein

Nerve supply

The sensory and motor innervation to the lower limb is supplied by the

The lumbar plexus is formed lateral to the

The

The genitofemoral nerve (L1, L2) leaves psoas major below the two former nerves, immediately divides into two branches that descends along the muscle's anterior side. The sensory femoral branch supplies the skin below the inguinal ligament, while the mixed genital branch supplies the skin and muscles around the sex organ. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (L2, L3) leaves psoas major laterally below the previous nerve, runs obliquely and laterally downward above the iliacus, exits the pelvic area near the iliac spine, and supplies the skin of the anterior thigh.[46]

The

The nerves of the sacral plexus pass behind the hip joint to innervate the posterior part of the thigh, most of the lower leg, and the foot.

The

Lower leg and foot

The lower leg and ankle need to keep exercised and moving well as they are the base of the whole body. The lower extremities must be strong in order to balance the weight of the rest of the body, and the

Exercises

Isometric and standard

There are a number of exercises that can be done to strengthen the lower leg. For example, in order to activate

Clinical significance

Lower leg injury

Lower leg injuries are common while running or playing sports. About 10% of all injuries in athletes involve the lower extremities.

Types of activities

Injuries to quadriceps or hamstrings are caused by the constant impact loads to the legs during activities, such as kicking a ball. While doing this type of motion, 85% of that shock is absorbed to the hamstrings; this can cause strain to those muscles.[57]

- Jumping – is another risk because if the legs do not land properly after an initial jump, there may be damage to the meniscus in the knees, sprain to the ankle by everting or inverting the foot, or damage to the Achilles tendon and gastrocnemius if there is too much force while plantar flexing.[57]

- Weight lifting – such as the improperly performed deep squat, is also dangerous to the lower limbs, because the exercise can lead to an overextension, or an outstretch, of our ligaments in the knee and can cause pain over time.[57]

- Running – the most common activity associated with lower leg injury. There is constant pressure and stress being put on the feet, knees, and legs while running by gravitational force. Muscle tears in our legs or pain in various areas of the feet can be a result of poor biomechanics of running.

Running

The most common injuries in running involve the knees and the feet. Various studies have focused on the initial cause of these running related injuries and found that there are many factors that correlate to these injuries. Female distance runners who had a history of stress fracture injuries had higher vertical impact forces than non-injured subjects.[58] The large forces onto the lower legs were associated with gravitational forces, and this correlated with patellofemoral pain or potential knee injuries.[58] Researchers have also found that these running-related injuries affect the feet as well, because runners with previous injuries showed more foot eversion and over-pronation while running than non-injured runners.[59] This causes more loads and forces on the medial side of the foot, causing more stress on the tendons of the foot and ankle.[59] Most of these running injuries are caused by overuse: running longer distances weekly for a long duration is a risk for injuring the lower legs.[60]

Prevention tools

Voluntary stretches to the legs, such as the wall stretch, condition the hamstrings and the calf muscle to various movements before vigorously working them.[61] The environment and surroundings, such as uneven terrain, can cause the feet to position in an unnatural way, so wearing shoes that can absorb forces from the ground's impact and allow for stabilizing the feet can prevent some injuries while running as well. Shoes should be structured to allow friction-traction at the shoe surface, space for different foot-strike stresses, and for comfortable, regular arches for the feet.[57]

Summary

The chance of damaging our lower extremities will be reduced by having knowledge about some activities associated with lower leg injury and developing a correct form of running, such as not over-pronating the foot or overusing the legs. Preventative measures, such as various stretches, and wearing appropriate footwear, will also reduce injuries.

Fracture

A fracture of the leg can be classified according to the involved bone into:

- Femoral fracture (in the upper leg)

- Crus fracture (in the lower leg)

Pain management

Lower leg and foot pain management is critical in reducing the progression of further injuries, uncomfortable sensations and limiting alterations while walking and running. Most individuals suffer from various pains in their

Plantar fasciitis

A plantar fasciitis foot stretch is one of the recommended methods to reduce pain caused by plantar fasciitis (Figure 1). To do the plantar fascia stretch, while sitting in a chair place the ankle on the opposite knee and hold the toes of the impaired foot, slowly pulling back. The stretch should be held for approximately ten seconds, three times per day.[62]

Medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splint)

Several methods can be utilized to help control pain caused by

Achilles tendinopathy

There are numerous appropriate approaches to handling pain resulting from

Society and culture

In Norse mythology, the race of Jotuns was born from the legs of Ymir. In Finnic mythology, the Earth was created from the shards of the egg of a goldeneye that fell from the knees of Ilmatar. While this story isn't found in other Finno-Ugric mythologies, Pavel Melnikov-Pechersky has noted several times that the beauty of legs is commonly mentioned in Mordvin mythology as a characteristic of both female mythological characters and real Erzyan and Mokshan women.

In medieval Europe, showing legs was one of the biggest taboos for women, especially the ones with a high social status. In Victorian England several centuries later legs were not to be mentioned at all (not only human ones, but even those of a table or a piano), and referred to as "limbs" instead.[65] Miniskirts and other clothing that reveal legs first became popular in mid-20th century science fiction. Since then, it became mainstream in Western cultures, with female legs frequently being focused on in films, TV ads, music videos, dance shows and various kinds of sports (i.e. ice skating or women's gymnastics).[66]

Many men who are attracted to female legs tend to regard them aesthetically almost as much as they do sexually, perceiving legs as more elegant, suggestive, sensual, or seductive (especially with clothing that makes legs easy to be revealed and concealed), whereas female breasts or buttocks are viewed as much more "in your face" sexual.[66] That said, legs (especially the inside of the upper leg that has the most sensitive and delicate skin) are considered to be one of the most sexualized elements of a woman's body, especially in Hollywood movies.[67]

Both men and women generally consider long legs attractive,[68] which may explain the preference for tall fashion models. Men also tend to favor women who have a higher leg length to body ratio, but the opposite is true of women's preferences in men.[66]

Adolescent and adult women in many Western cultures often remove the hair from their legs.[69] Toned, tanned, shaved legs are sometimes perceived as a sign of youthfulness and are often considered attractive in these cultures.

Men generally do not shave their legs in any culture. However, leg-shaving is a generally accepted practice in modeling. It is also fairly common in sports where the hair removal makes the athlete appreciably faster by reducing drag; the most common case of this is competitive swimming.[70]

Image gallery

-

Surface anatomy of human leg

-

Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions

-

Small saphenous vein and its tributaries

-

The popliteal, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries

-

Nerves of the right lower extremity, posterior view

-

Leg bones

See also

- Distraction osteogenesis (leg lengthening)

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-32771-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-128-04096-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-662-46810-4.

- PMID 18383647.

- OCLC 928962548.

- ISBN 978-1-119-66286-0.

- ISBN 978-0-313-39176-7.

- ISBN 978-0-702-07259-8.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 360

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 361

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 362

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 196

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), pp. 244–47

- ^ a b Platzer, (2004), p. 232

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 234

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 236

- ISBN 9781496347213.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Platzer (2004), p. 238

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 240

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 242

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 252

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 248

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 250

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 264

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 266

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 256

- ISBN 978-0-8036-4503-5.

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 258

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 260

- ^ Chaitow (2000), p. 554

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 262

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 268

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 270

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 272

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 274

- ^ a b c Alter, M. J. (2004). Science of Flexibility (3rd ed., pp. 1–6). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- ^ a b c Lower Extremity Stretching Home Exercise Program (April 2010). In Aurora Healthcare.

- ^ Nelson, A. G., & Kokkonen, J. (2007). Stretching Anatomy. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- ^ Weppler, C. H., & Magnusson, S. P. (March 2010). Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation. Physical Therapy, 90, 438–49.

- ^ Roth, E. Step Stretch for the Foot. AZ Central. http://healthyliving.azcentral.com/step-stretch-foot-18206.html

- ^ a b Shea, K. (12 August 2013). Shin Stretches for Runners. Livestrong. http://www.livestrong.com/article/353394-shin-stretches-for-runners/

- ^ a b c Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 464

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 412

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp. 466–67

- ^ a b c d Thieme Atlas of anatomy (2006), pp. 470–71

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of anatomy (2006), pp. 472–73

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of anatomy (2006), pp. 474–75

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 476

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp. 480–81

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp. 482–83

- PMID 24717406. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 April 2019.

- PMID 24717405.

- ISBN 978-1-936608-58-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7360-9226-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-8291-3.

- ^ a b Kjaer, M., Krogsgaard, M., & Magnusson, P. (Eds.). (2008). Textbook of Sports Medicine Basic Science and Clinical Aspects of Sports Injury and Physical Activity. Chichester, GBR: John Wiley & Sons.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e Bartlett, R. (1999). Sports Biomechanics: Preventing Injury and Improving Performance. London, GBR: Spon Press.[page needed]

- ^ hdl:10520/EJC48590.

- ^ PMID 16311200.

- PMID 25174773.

- ^ Spiker, Ted (7 March 2007). "Build Stronger Lower Legs". Runner's World.

- PMID 17722355.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Garl, Tim (2004). "Lower Leg Pain in Basketball Players". FIBA Assist Magazine: 61–62.

- S2CID 36134550.

- ^ Swati Gautam. "When legs were taboo". Telegraph India. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Leon F. Seltzer. "Why Do Men Find Women's Legs So Alluring?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Smith, Lauren E., «A Leg Up For Women? Stereotypes of Female Sexuality in American Culture through an Analysis of Iconic Film Stills of Women’s Legs». Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2013.

- ^ Ian Sample. "Why men and women find longer legs more attractive". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Phil Edwards. "How the beauty industry convinced women to shave their legs". Vox. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Michelle Martin. "Why Men Should Shave Their Legs". TriathlonOz. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

Literature specified by multiple pages above:

- Chaitow, Leon; Walker DeLany, Judith (2000). Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques: The Lower Body. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-443-06284-6. Archived from the originalon 24 September 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- consulting editors, Lawrence M. Ross, Edward D. Lamperti; authors, Michael Schuenke, Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.)

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). ISBN 3-13-533305-1.