Hydrogen peroxide

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Hydrogen peroxide

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Peroxol | |||

| Other names

Dioxidane

Oxidanyl Perhydroxic acid 0-hydroxyol Oxygenated water Peroxaan | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.028.878 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

IUPHAR/BPS |

|||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

RTECS number

|

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2015 (>60% soln.) 2014 (20–60% soln.) 2984 (8–20% soln.) | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H2O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 34.014 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Very light blue liquid | ||

| Odor | slightly sharp | ||

| Density | 1.11 g/cm3 (20 °C, 30% (w/w) solution)[1] 1.450 g/cm3 (20 °C, pure) | ||

| Melting point | −0.43 °C (31.23 °F; 272.72 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 150.2 °C (302.4 °F; 423.3 K) (decomposes) | ||

Miscible

| |||

| Solubility | soluble in ether, alcohol insoluble in petroleum ether | ||

| log P | −0.43[2] | ||

| Vapor pressure | 5 mmHg (30 °C)[3] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 11.75 | ||

| −17.7·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.4061 | ||

| Viscosity | 1.245 cP (20 °C) | ||

| 2.26 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

1.267 J/(g·K) (gas) 2.619 J/(g·K) (liquid) | ||

Std enthalpy of (ΔfH⦵298)formation |

−187.80 kJ/mol | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| A01AB02 (WHO) D08AX01 (WHO), D11AX25 (WHO), S02AA06 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H271, H302, H314, H332, H335, H412 | |||

| P280, P305+P351+P338, P310 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

1518 mg/kg[citation needed] 2000 mg/kg (oral, mouse)[4] | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

1418 ppm (rat, 4 hr)[4] | ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

227 ppm (mouse)[4] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1 ppm (1.4 mg/m3)[3] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 1 ppm (1.4 mg/m3)[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

75 ppm[3] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0164 (>60% soln.) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Hydrogen peroxide is a

Hydrogen peroxide is a

Properties

The boiling point of H2O2 has been extrapolated as being 150.2 °C (302.4 °F), approximately 50 °C (90 °F) higher than water. In practice, hydrogen peroxide will undergo potentially explosive thermal decomposition if heated to this temperature. It may be safely distilled at lower temperatures under reduced pressure.[7]

Hydrogen peroxide forms stable adducts with urea (Hydrogen peroxide - urea), sodium carbonate (sodium percarbonate) and other compounds.[8] An acid-base adduct with triphenylphosphine oxide is a useful "carrier" for H2O2 in some reactions.

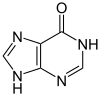

Structure

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a nonplanar molecule with (twisted) C2

The approximately 100°

The molecular structures of gaseous and

Aqueous solutions

In

| H2O2 ( w/w ) |

Density (g/cm3) |

Temp. (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| 3% | 1.0095 | 15 |

| 27% | 1.10 | 20 |

| 35% | 1.13 | 20 |

| 50% | 1.20 | 20 |

| 70% | 1.29 | 20 |

| 75% | 1.33 | 20 |

| 96% | 1.42 | 20 |

| 98% | 1.43 | 20 |

| 100% | 1.45 | 20 |

Hydrogen peroxide is most commonly available as a solution in water. For consumers, it is usually available from pharmacies at 3 and 6

Comparison with analogues

Hydrogen peroxide has several structural analogues with HmX−XHn bonding arrangements (water also shown for comparison). It has the highest (theoretical) boiling point of this series (X = O, S, N, P). Its melting point is also fairly high, being comparable to that of hydrazine and water, with only hydroxylamine crystallising significantly more readily, indicative of particularly strong hydrogen bonding. Diphosphane and hydrogen disulfide exhibit only weak hydrogen bonding and have little chemical similarity to hydrogen peroxide. Structurally, the analogues all adopt similar skewed structures, due to repulsion between adjacent lone pairs.

| Name | Formula | Molar mass (g/mol) |

Melting point (°C) |

Boiling point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | HOH | 18.02 | 0.00 | 99.98 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | HOOH | 34.01 | −0.43 | 150.2* |

| Hydrogen disulfide | HSSH | 66.15 | −89.6 | 70.7 |

| Hydrazine | H2NNH2 | 32.05 | 2 | 114 |

| Hydroxylamine | NH2OH | 33.03 | 33 | 58* |

| Diphosphane | H2PPH2 | 65.98 | −99 | 63.5* |

Natural occurrence

Hydrogen peroxide is produced by various biological processes mediated by enzymes.

Hydrogen peroxide has been detected in surface water, in groundwater, and in the

The amount of hydrogen peroxide in biological systems can be assayed using a fluorometric assay.[18]

Discovery

Alexander von Humboldt is sometimes said to have been the first to report the first synthetic peroxide, barium peroxide, in 1799 as a by-product of his attempts to decompose air, although this is disputed due to von Humboldt's ambiguous wording.[19] Nineteen years later Louis Jacques Thénard recognized that this compound could be used for the preparation of a previously unknown compound, which he described as eau oxygénée ("oxygenated water") – subsequently known as hydrogen peroxide.[20][21][22]

An improved version of Thénard's process used hydrochloric acid, followed by addition of sulfuric acid to precipitate the barium sulfate byproduct. This process was used from the end of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century.[23]

The bleaching effect of peroxides and their salts on

Early attempts failed to produce neat hydrogen peroxide. Anhydrous hydrogen peroxide was first obtained by vacuum distillation.[24]

Determination of the molecular structure of hydrogen peroxide proved to be very difficult. In 1892, the Italian physical chemist Giacomo Carrara (1864–1925) determined its molecular mass by freezing-point depression, which confirmed that its molecular formula is H2O2.[25] H2O=O seemed to be just as possible as the modern structure, and as late as in the middle of the 20th century at least half a dozen hypothetical isomeric variants of two main options seemed to be consistent with the available evidence.[26] In 1934, the English mathematical physicist William Penney and the Scottish physicist Gordon Sutherland proposed a molecular structure for hydrogen peroxide that was very similar to the presently accepted one.[27][28]

Production

In 1994, world production of H2O2 was around 1.9 million tonnes and grew to 2.2 million in 2006,

Today, hydrogen peroxide is manufactured almost exclusively by the anthraquinone process, which was originally developed by BASF in 1939. It begins with the reduction of an anthraquinone (such as 2-ethylanthraquinone or the 2-amyl derivative) to the corresponding anthrahydroquinone, typically by hydrogenation on a palladium catalyst. In the presence of oxygen, the anthrahydroquinone then undergoes autoxidation: the labile hydrogen atoms of the hydroxy groups transfer to the oxygen molecule, to give hydrogen peroxide and regenerating the anthraquinone. Most commercial processes achieve oxidation by bubbling compressed air through a solution of the anthrahydroquinone, with the hydrogen peroxide then extracted from the solution and the anthraquinone recycled back for successive cycles of hydrogenation and oxidation.[30][31]

The net reaction for the anthraquinone-catalyzed process is:[30]

- H2 + O2 → H2O2

The economics of the process depend heavily on effective recycling of the extraction solvents, the hydrogenation catalyst and the expensive quinone.

Historical methods

Hydrogen peroxide was once prepared industrially by hydrolysis of ammonium persulfate:

- [NH4]2S2O8 + 2 H2O → 2 [NH4]HSO4 + H2O2

[NH4]2S2O4 was itself obtained by the electrolysis of a solution of ammonium bisulfate ([NH4]HSO4) in sulfuric acid.[32]

Other routes

Small amounts are formed by electrolysis, photochemistry, and electric arc, and related methods.[33]

A commercially viable route for hydrogen peroxide via the reaction of hydrogen with oxygen favours production of water but can be stopped at the peroxide stage.[34][35] One economic obstacle has been that direct processes give a dilute solution uneconomic for transportation. None of these has yet reached a point where it can be used for industrial-scale synthesis.

Reactions

Acid-base

Hydrogen peroxide is about 1000 times stronger as an acid than water.[36]

- H2O2 ⇌ H+ + HO−2 pK = 11.65

Disproportionation

Hydrogen peroxide disproportionates to form water and oxygen with a

of 70.5 J/(mol·K):- 2 H2O2 → 2 H2O + O2

The rate of decomposition increases with rise in temperature, concentration, and pH. H2O2 is unstable under alkaline conditions. Decomposition is catalysed by various redox-active ions or compounds, including most transition metals and their compounds (e.g. manganese dioxide (MnO2), silver, and platinum).[38]

Oxidation reactions

The

Oxidizing reagent |

Reduced product |

Oxidation potential (V) |

|---|---|---|

| F2 | HF | 3.0 |

| O3 | O2 | 2.1 |

| H2O2 | H2O | 1.8 |

| KMnO4 | MnO2 | 1.7 |

| ClO2 | HClO | 1.5 |

| Cl2 | Cl− | 1.4 |

Sulfite (SO2−3) is oxidized to sulfate (SO2−4).

Reduction reactions

Under

- NaOCl + H2O2 → O2 + NaCl + H2O

- 2 KMnO4 + 3 H2O2 → 2 MnO2 + 2 KOH + 2 H2O + 3 O2

The oxygen produced from hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite is in the singlet state.

Although usually a reductant, alkaline hydrogen peroxide converts Mn(II) to the dioxide:

- H2O2 + Mn2+ + 2 OH− → MnO2 + 2 H2O

In a related reaction, potassium permanganate is reduced to Mn2+ by acidic H2O2:[5]

- 2 MnO−4 + 5 H2O2 + 6 H+ → 2 Mn2+ + 8 H2O + 5 O2

Organic reactions

Hydrogen peroxide is frequently used as an

- Ph-S-CH3 + H2O2 → Ph-S(O)-CH3 + H2O

Alkaline hydrogen peroxide is used for

Precursor to other peroxide compounds

Hydrogen peroxide is a weak acid, forming hydroperoxide or peroxide salts with many metals.

It also converts metal oxides into the corresponding peroxides. For example, upon treatment with hydrogen peroxide, chromic acid (CrO3 and H2SO4) forms a blue peroxide CrO(O2)2.

Biochemistry

Production

The aerobic oxidation of glucose in the presence of the enzyme

- C6H12O7 + O2 → C6H10O7 + H2O2

Superoxide dismutases (SOD)s are enzymes that promote the disproportionation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide.[43]

- 2 O−2 + 2 H+ → O2 + H2O2

- 2 H2O2 → O2 + 2 H2O

- R-CH2-CH2-CO-SCoA + O2 R-CH=CH-CO-SCoA + H2O2

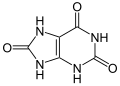

Hydrogen peroxide arises by the degradation of adenosine monophosphate, which yields hypoxanthine. Hypoxanthine is then oxidatively catabolized first to xanthine and then to uric acid, and the reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme xanthine oxidase:[47]

The degradation of guanosine monophosphate yields xanthine as an intermediate product which is then converted in the same way to uric acid with the formation of hydrogen peroxide.[47]

Consumption

Catalase, another peroxisomal enzyme, uses this H2O2 to oxidize other substrates, including phenols, formic acid, formaldehyde, and alcohol, by means of a peroxidation reaction:

- H2O2 + R'H2 → R' + 2 H2O

thus eliminating the poisonous hydrogen peroxide in the process.

This reaction is important in liver and kidney cells, where the peroxisomes neutralize various toxic substances that enter the blood. Some of the ethanol humans drink is oxidized to acetaldehyde in this way.[48] In addition, when excess H2O2 accumulates in the cell, catalase converts it to H2O through this reaction:

- H2O2 → 0.5 O2 + H2O

Glutathione peroxidase, a selenoenzyme, also catalyzes the disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide.

Fenton reaction

The reaction of

- Fe(II) + H2O2 → Fe(III)OH + HO·

The fenton reaction explains the toxicity of hydrogen peroxides because the hydroxyl radicals rapidly and irreversibly oxidize all organic compounds, including

Function

Eggs of sea urchin, shortly after fertilization by a sperm, produce hydrogen peroxide. It is then converted to hydroxyl radicals (HO•), which initiate radical polymerization, which surrounds the eggs with a protective layer of polymer.

The

As a proposed

At least one study has also tried to link hydrogen peroxide production to cancer.[59]

Uses

Bleaching

About 60% of the world's production of hydrogen peroxide is used for pulp- and paper-bleaching.[29] The second major industrial application is the manufacture of sodium percarbonate and sodium perborate, which are used as mild bleaches in laundry detergents. A representative conversion is:

- Na2B4O7 + 4 H2O2 + 2 NaOH → 2 Na2B2O4(OH)4 + H2O

Sodium percarbonate, which is an adduct of

Hydrogen peroxide has also been used as a flour bleaching agent and a tooth and bone whitening agent.

Production of organic peroxy compounds

It is used in the production of various

Production of inorganic peroxides

The reaction with borax leads to sodium perborate, a bleach used in laundry detergents:

- Na2B4O7 + 4 H2O2 + 2 NaOH → 2 Na2B2O4(OH)4 + H2O

Sewage treatment

Hydrogen peroxide is used in certain waste-water treatment processes to remove organic impurities. In

Disinfectant

Hydrogen peroxide may be used for the sterilization of various surfaces,

Hydrogen peroxide is seen as an environmentally safe alternative to

Propellant

High-concentration H2O2 is referred to as "high-test peroxide" (HTP). It can be used as either a

In bipropellant applications, H2O2 is decomposed to oxidize a burning fuel. Specific impulses as high as 350 s (3.5 kN·s/kg) can be achieved, depending on the fuel. Peroxide used as an oxidizer gives a somewhat lower Isp than liquid oxygen but is dense, storable, and non-cryogenic and can be more easily used to drive gas turbines to give high pressures using an efficient closed cycle. It may also be used for regenerative cooling of rocket engines. Peroxide was used very successfully as an oxidizer in World War II German rocket motors (e.g.,

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Hellmuth Walter KG–conceived turbine used hydrogen peroxide for use in submarines while submerged; it was found to be too noisy and require too much maintenance compared to diesel-electric power systems. Some torpedoes used hydrogen peroxide as oxidizer or propellant. Operator error in the use of hydrogen-peroxide torpedoes was named as possible causes for the sinking of HMS Sidon and the Russian submarine Kursk.[77] SAAB Underwater Systems is manufacturing the Torpedo 2000. This torpedo, used by the Swedish Navy, is powered by a piston engine propelled by HTP as an oxidizer and kerosene as a fuel in a bipropellant system.[78][79]

Household use

Hydrogen peroxide has various domestic uses, primarily as a cleaning and disinfecting agent.

- Hair bleaching

Diluted H2O2 (between 1.9% and 12%) mixed with

- Removal of blood stains

Hydrogen peroxide reacts with blood as a bleaching agent, and so if a blood stain is fresh, or not too old, liberal application of hydrogen peroxide, if necessary in more than single application, will bleach the stain fully out. After about two minutes of the application, the blood should be firmly blotted out.[83][84]

- Acne treatment

Hydrogen peroxide may be used to treat

- Oral cleaning agent

The use of dilute hydrogen peroxide as a oral cleansing agent has been reviewed academically to determine its usefulness in treating gingivitis and plaque. Although there is a positive effect when compared with a placebo, it was concluded that chlorhexidine is a much more effective treatment.[86]

Niche uses

- Horticulture

Some horticulturists and users of hydroponics advocate the use of weak hydrogen peroxide solution in watering solutions. Its spontaneous decomposition releases oxygen that enhances a plant's root development and helps to treat root rot (cellular root death due to lack of oxygen) and a variety of other pests.[87][88]

For general watering concentrations, around 0.1% is in use. This can be increased up to one percent for antifungal actions.[89] Tests show that plant foliage can safely tolerate concentrations up to 3%.[90]

- Fishkeeping

Hydrogen peroxide is used in aquaculture for controlling mortality caused by various microbes. In 2019, the U.S. FDA approved it for control of Saprolegniasis in all coldwater finfish and all fingerling and adult coolwater and warmwater finfish, for control of external columnaris disease in warm-water finfish, and for control of Gyrodactylus spp. in freshwater-reared salmonids.[91] Laboratory tests conducted by fish culturists have demonstrated that common household hydrogen peroxide may be used safely to provide oxygen for small fish. The hydrogen peroxide releases oxygen by decomposition when it is exposed to catalysts such as manganese dioxide.

- Removing yellowing from aged plastics

Hydrogen peroxide may be used in combination with a UV-light source to remove yellowing from white or light grey acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastics to partially or fully restore the original color. In the retrocomputing scene, this process is commonly referred to as retrobright.

Safety

Regulations vary, but low concentrations, such as 5%, are widely available and legal to buy for medical use. Most over-the-counter peroxide solutions are not suitable for ingestion. Higher concentrations may be considered hazardous and typically are accompanied by a safety data sheet (SDS). In high concentrations, hydrogen peroxide is an aggressive oxidizer and will corrode many materials, including human skin. In the presence of a reducing agent, high concentrations of H2O2 will react violently.[92] While concentrations up to 35% produce only "white" oxygen bubbles in the skin (and some biting pain) that disappear with the blood within 30–45 minutes, concentrations of 98% dissolve paper. However, concentrations as low as 3% can be dangerous for the eye because of oxygen evolution within the eye.[93]

High-concentration hydrogen peroxide streams, typically above 40%, should be considered hazardous due to concentrated hydrogen peroxide's meeting the definition of a DOT oxidizer according to U.S. regulations if released into the environment. The EPA Reportable Quantity (RQ) for D001 hazardous wastes is 100 pounds (45 kg), or approximately 10 US gallons (38 L), of concentrated hydrogen peroxide.

Hydrogen peroxide should be stored in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area and away from any flammable or combustible substances. It should be stored in a container composed of non-reactive materials such as stainless steel or glass (other materials including some plastics and aluminium alloys may also be suitable).[94] Because it breaks down quickly when exposed to light, it should be stored in an opaque container, and pharmaceutical formulations typically come in brown bottles that block light.[95]

Hydrogen peroxide, either in pure or diluted form, may pose several risks, the main one being that it forms explosive mixtures upon contact with organic compounds.[96] Distillation of hydrogen peroxide at normal pressures is highly dangerous. It is also corrosive, especially when concentrated, but even domestic-strength solutions may cause irritation to the eyes, mucous membranes, and skin.[97] Swallowing hydrogen peroxide solutions is particularly dangerous, as decomposition in the stomach releases large quantities of gas (ten times the volume of a 3% solution), leading to internal bloating. Inhaling over 10% can cause severe pulmonary irritation.[98]

With a significant vapour pressure (1.2 kPa at 50 °C),

Wound healing

Historically, hydrogen peroxide was used for disinfecting wounds, partly because of its low cost and prompt availability compared to other antiseptics.[103]

There is conflicting evidence on hydrogen peroxide's effect on wound healing. Some research finds benefit, while other research find delays and healing inhibition.[104] Its use for home treatment of wounds is generally not recommended.[105] 1.5–3% hydrogen peroxide is used as a disinfectant in dentistry, especially in endodotic treatments together with hypochlorite and chlorhexidin and 1–1.5% is also useful for treatment of inflammation of third molars (wisdom teeth).[106]

Use in alternative medicine

Practitioners of

Both the effectiveness and safety of hydrogen peroxide therapy is scientifically questionable. Hydrogen peroxide is produced by the immune system, but in a carefully controlled manner. Cells called phagocytes engulf pathogens and then use hydrogen peroxide to destroy them. The peroxide is toxic to both the cell and the pathogen and so is kept within a special compartment, called a phagosome. Free hydrogen peroxide will damage any tissue it encounters via oxidative stress, a process that also has been proposed as a cause of cancer.[112] Claims that hydrogen peroxide therapy increases cellular levels of oxygen have not been supported. The quantities administered would be expected to provide very little additional oxygen compared to that available from normal respiration. It is also difficult to raise the level of oxygen around cancer cells within a tumour, as the blood supply tends to be poor, a situation known as tumor hypoxia.

Large oral doses of hydrogen peroxide at a 3% concentration may cause irritation and blistering to the mouth, throat, and abdomen as well as abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.[108] Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide at concentrations of 35% or higher has been implicated as the cause of numerous gas embolism events resulting in hospitalisation. In these cases, hyperbaric oxygen therapy was used to treat the embolisms.[113]

Intravenous injection of hydrogen peroxide has been linked to several deaths.[114][110][111] The American Cancer Society states that "there is no scientific evidence that hydrogen peroxide is a safe, effective, or useful cancer treatment."[109] Furthermore, the therapy is not approved by the U.S. FDA.

Historical incidents

- On 16 July 1934, in Kummersdorf, Germany, a propellant tank containing an experimental monopropellant mixture consisting of hydrogen peroxide and ethanol exploded during a test, killing three people.[115]

- During the Second World War, doctors in German concentration camps experimented with the use of hydrogen peroxide injections in the killing of human subjects.[116]

- In December 1943, the pilot Messerschmitt Me 163.

- In June 1955, Royal Navy submarine HMS Sidon sank after leaking high-test peroxide in a torpedo caused it to explode in its tube, killing twelve crew members; a member of the rescue party also succumbed.

- In April 1992, an explosion occurred at the hydrogen peroxide plant at Jarrie in France, due to technical failure of the computerised control system and resulting in one fatality and wide destruction of the plant.[117]

- Several people received minor injuries after a hydrogen peroxide spill on board a Northwest Airlines flight from Orlando, Florida to Memphis, Tennessee on 28 October 1998.[118]

- The Russian submarine HTP, a form of highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide used as propellant for the torpedo, seeped through its container, damaged either by rust or in the loading procedure on land where an incident involving one of the torpedoes accidentally touching ground went unreported. The vessel was lost with all hands.[119]

- On 15 August 2010, a spill of about 30 US gallons (110 L) of cleaning fluid occurred on the 54th floor of 1515 Broadway, in hazmat situation. There were no reported injuries.[120]

See also

- FOX reagent, used to measure levels of hydrogen peroxide in biological systems

- Hydrogen chalcogenide

- Retrobright, a process using hydrogen peroxide to restore yellowed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic

- Bis(trimethylsilyl) peroxide, an aprotic substitute

References

- S2CID 96669623.

- ^ "Hydrogen peroxide". www.chemsrc.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0335". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c "Hydrogen peroxide". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ ISBN 0130-39913-2.

- ISBN 978-1-86094-268-6. Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-12-126601-1.

- ISSN 1528-7483.

- (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- .

- hdl:2027.42/71115. Archived(PDF) from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- S2CID 9564774.

- ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- .

- ^ "Hydrogen Peroxide Technical Library" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ .

- ^ Special Report No. 10. Hydrogen Peroxide. OEL Criteria Document. CAS No. 7722-84-1. July 1996.

- from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- PMID 33317108.

I checked Humboldt's pertinent publication carefully, but was unable to find an unambiguous proof of this assumption; the description of the starting materials ("Alaun-Erden" or "schwere Erden") were just too unprecise to understand what kind of chemical experiments he performed.

- .

- ^ Thénard LJ (1818). "Observations sur des nouvelles combinaisons entre l'oxigène et divers acides". Annales de chimie et de physique. 2nd series. 8: 306–312. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

Hydrogen peroxide was discovered in 1818 by the French chemist Louis-Jacques Thenard, who named it eau oxygénée (oxygenated water).

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85404-536-5.

- from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Carrara G (1892). "Sul peso molecolare e sul potere rifrangente dell' acqua ossigenata" [On the molecular weight and on the refracting power of hydrogen peroxide]. Atti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei. 1 (2): 19–24. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016.

Carrara's findings were confirmed by: W. R. Orndorff and John White (1893) "The molecular weight of hydrogen peroxide and of benzoyl peroxide," Archived 4 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine American Chemical Journal, 15 : 347–356. - ^ See, for example:

- In 1882, Kingzett proposed as a structure H2O=O. See: Kingzett T (29 September 1882). "On the activity of oxygen and the mode of formation of hydrogen dioxide". The Chemical News. 46 (1192): 141–142. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- In his 1922 textbook, Joseph Mellor considered three hypothetical molecular structures for hydrogen peroxide, admitting (p. 952): "... the constitution of this compound has not been yet established by unequivocal experiments". See: Joseph William Mellor, A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry, vol. 1 (London, England: Longmans, Green and Co., 1922), p. 952–956. Archived 3 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- W. C. Schumb, C. N. Satterfield, and R. L. Wentworth (1 December 1953) "Report no. 43: Hydrogen peroxide, Part two" Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Office of Naval Research, Contract No. N5ori-07819 On p. 178, the authors present six hypothetical models (including cis-trans isomers) for hydrogen peroxide's molecular structure. On p. 184, the present structure is considered almost certainly correct—although a small doubt remained. (Note: The report by Schumb et al. was reprinted as: W. C. Schumb, C. N. Satterfield, and R. L. Wentworth, Hydrogen Peroxide (New York, New York: Reinhold Publishing Corp. (American Chemical Society Monograph), 1955).)

- .

- .

- ^ from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ S2CID 23286196.

- ^ H. Riedl and G. Pfleiderer, U.S. Patent 2,158,525 (2 October 1936 in the US, and 10 October 1935 in Germany) to I. G. Farbenindustrie, Germany

- ^ "Preparing to manufacture hydrogen peroxide" (PDF). IDC Technologies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Mellor JW (1922). Modern Inorganic Chemistry. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 192–195.

- S2CID 1828874.

- ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ "Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide - Kinetics and Review of Chosen Catalysts" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-13-149330-8.

- .

- .

- PMID 29741385.

- S2CID 2246466.

- ISBN 3-540-18163-6(in German)

- PMID 20124343.

- PMID 16756494.

- ISBN 3-540-41813-X. Archived from the originalon 28 February 2017.

- ^ ISBN 3-540-41813-X(in German)

- ISBN 3-527-32839-4p. 112

- ISBN 3-540-18163-6(in German)

- ^ a b Halliwell B, Adhikary A, Dingfelder M, Dizdaroglu M . Hydroxyl radical is a significant player in oxidative DNA damage in vivo. Chem Soc Rev. 2021 Aug 7;50(15):8355-8360. doi: 10.1039/d1cs00044f. Epub 2021 Jun 15. PMID 34128512; PMCID: PMC8328964

- S2CID 6407526.

- .

- PMID 23675144.

- .

- ^ Weber CG (Winter 1981). "The Bombardier Beetle Myth Exploded". Creation/Evolution. 2 (1): 1–5. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Isaak M (30 May 2003). "Bombardier Beetles and the Argument of Design". TalkOrigins Archive. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- PMID 17434122.

- ^ "Wie Pflanzen sich schützen, Helmholtz-Institute of Biochemical Plant Pathology (in German)" (PDF) (in German). Helmholtz-Institute of Biochemical Plant Pathology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- PMID 17150302.

- ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ISBN 978-0-203-91255-3.

- S2CID 93052585.

- .

- ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8247-9524-5.

- PMID 15356786.

- PMID 21392848.

- ISBN 978-0-683-30740-5.

- ^ a b "Chemical Disinfectants - Disinfection & Sterilization Guidelines - Guidelines Library - Infection Control - CDC". www.cdc.gov. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- PMID 9880479.

- ISBN 978-0-683-30740-5.

- ^ "Sec. 184.1366 Hydrogen peroxide". U.S. Government Printing Office via GPO Access. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ Wernimont EJ (9–12 July 2006). System Trade Parameter Comparison of Monopropellants: Hydrogen Peroxide vs Hydrazine and Others (PDF). 42nd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit. Sacramento, California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2014.

- ^ Ventura M, Mullens P (19 June 1999). "The Use of Hydrogen Peroxide for Propulsion and Power" (PDF). General Kinetics, LLC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Cieśliński D (2021). "Polish civil rockets' development overview". Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Nucleus: A Very Different Way to Launch into Space". Nammo. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Peroxide Accident – Walter Web Site". Histarmar.com.ar. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ Scott R (November 1997). "Homing Instincts". Jane's Navy Steam Generated by Catalytic Decomposition of 80–90% Hydrogen Peroxide Was Used for Driving the Turbopump Turbines of the V-2 Rockets, the X-15 Rocketplanes, the Early Centaur RL-10 Engines and is Still Used on Soyuz for That Purpose Today. International. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "Soyuz using hydrogen peroxide propellant". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-19-860783-0. Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- PMID 15053912.

- ^ Shepherd S. "Brushing Up on Gum Disease". FDA Consumer. Archived from the original on 14 May 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ Gibbs KB (14 November 2016). "How to remove blood stains from clothes and furniture". Today.com. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Mayntz M. "Dried Blood Stain Removal". Lovetoknow.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- S2CID 2611939.

- PMID 33178277.

- ^ "Ways to use Hydrogen Peroxide in the Garden". Using Hydrogen Peroxide. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-12-000786-8.

- ^ "Hydrogen Peroxide for Plants and Garden". 7 September 2019. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Effect of hydrogen peroxide spraying on Hydrocotyle ranunculoides". Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "FDA Approves Additional Indications for 35% PEROX-AID (hydrogen peroxide) for Use in Certain Finfish". FDA. 26 July 2019. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Greene B, Baker D, Frazier W. "Hydrogen Peroxide Accidents and Incidents: What we can learn from history" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ see Hans Marquardt, Lehrbuch der Toxikologie

- ^ "Material Compatibility with Hydrogen Peroxide". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Hydrogen Peroxide Mouthwash is it Safe?". Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Hydrogen Peroxide". Archived from the original on 13 May 2013.

- ^ For example, see an "MSDS for a 3% peroxide solution". Archived from the original on 15 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ H2O2 toxicity and dangers Archived 5 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry website

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 76th Ed, 1995–1996

- ^ "CDC – Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH): Chemical Listing and Documentation of Revised IDLH Values – NIOSH Publications and Products". 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "Threshold Limit Values for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents & Biological Exposure Indices, ACGIH" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013.

- ^ "ATSDR – Redirect – MMG: Hydrogen Peroxide". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- S2CID 1028923.

- S2CID 35739209.

- ^ "Cleveleand Clinic: What Is Hydrogen Peroxide Good For?". December 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ see e.g. Detlev Heidemann, Endodontie, Urban&Fischer 2001

- ISBN 978-1-885236-07-4.

- ^ NOAA.

- ^ S2CID 36911297.

- ^ a b Mikkelson B (30 April 2006). "Hydrogen Peroxide". Snopes.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Naturopath Sentenced For Injecting Teen With Hydrogen Peroxide – 7NEWS Denver". Thedenverchannel.com. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- S2CID 850978.

- from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Cooper A (12 January 2005). "A Prescription for Death?". CBS News. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ "Heeresversuchsstelle Kummersdorf". UrbEx - Forgotten & Abandoned. 23 March 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ "The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide". Robert Jay Lifton. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ "Explosion and fire in a hydrogen peroxide plant". ARIA. November 2007. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Accident No: DCA-99-MZ-001" (PDF). U.S. National Transportation Safety Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Mizokami K (28 September 2018). "The True Story of the Russian Kursk Submarine Disaster". Archived from the original on 14 February 2022.

- ^ Wheaton S (16 August 2010). "Bleach Spill Shuts Part of Times Square". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

Bibliography

- DrabowiczJ, et al. (1994). Capozzi G, et al. (eds.). The Syntheses of Sulphones, Sulphoxides and Cyclic Sulphides. Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 112–6. ISBN 978-0-471-93970-2.

- Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. A great description of properties & chemistry of H2O2.

- March J (1992). Advanced Organic Chemistry (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 723.

- Hess WT (1995). "Hydrogen Peroxide". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Vol. 13 (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 961–995.

External links

- Hydrogen Peroxide at The Periodic Table of Videos(University of Nottingham)

- Material Safety Data Sheet

- ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry FAQ

- International Chemical Safety Card 0164

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Process flow sheet of Hydrogen Peroxide Production by anthrahydroquinone autoxidation

- Hydrogen Peroxide Handbook by Rocketdyne

- IR spectroscopic study J. Phys. Chem.

- Bleaching action of Hydrogen peroxide at YouTube

![{\displaystyle {\ce {->[{\ce {FAD}}]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cfe32866bbddda63271e58f329b21caad5946b64)