Hypertension

| Hypertension | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Arterial hypertension, high blood pressure |

| Causes | Usually lifestyle and genetic factors[5][6] |

| Risk factors | Lack of sleep, excess salt, excess body weight, smoking, alcohol,[1][5] air pollution[7] |

| Diagnostic method | Resting blood pressure 130/80 or 140/90 mmHg[5][8] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medications[9] |

| Frequency | 16–37% globally[5] |

| Deaths | 9.4 million / 18% (2010)[10] |

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a

High blood pressure is classified as

Blood pressure is classified by two measurements, the

Lifestyle changes and medications can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of health complications.

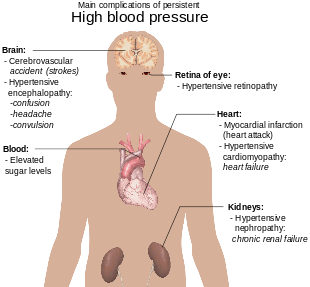

Signs and symptoms

Hypertension is rarely accompanied by

On

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension is hypertension due to an identifiable cause, and may result in certain specific additional signs and symptoms. For example, as well as causing high blood pressure,

Hypertensive crisis

Severely elevated blood pressure (equal to or greater than a systolic 180 or diastolic of 120) is referred to as a hypertensive crisis.[28] Hypertensive crisis is categorized as either hypertensive urgency or hypertensive emergency, according to the absence or presence of end organ damage, respectively.[29][30]

In hypertensive urgency, there is no evidence of end organ damage resulting from the elevated blood pressure. In these cases, oral medications are used to lower the BP gradually over 24 to 48 hours.[31]

In hypertensive emergency, there is evidence of direct damage to one or more organs.[32][33] The most affected organs include the brain, kidney, heart and lungs, producing symptoms which may include confusion, drowsiness, chest pain and breathlessness.[31] In hypertensive emergency, the blood pressure must be reduced more rapidly to stop ongoing organ damage;[31] however, there is a lack of randomized controlled trial evidence for this approach.[33]

Pregnancy

Hypertension occurs in approximately 8–10% of pregnancies.[27] Two blood pressure measurements six hours apart of greater than 140/90 mm Hg are diagnostic of hypertension in pregnancy.[34] High blood pressure in pregnancy can be classified as pre-existing hypertension, gestational hypertension, or pre-eclampsia.[35] Women who have chronic hypertension before their pregnancy are at increased risk of complications such as premature birth, low birthweight or stillbirth.[36] Women who have high blood pressure and had complications in their pregnancy have three times the risk of developing cardiovascular disease compared to women with normal blood pressure who had no complications in pregnancy.[37][38]

Pre-eclampsia is a serious condition of the second half of pregnancy and

In contrast, gestational hypertension is defined as new-onset hypertension during pregnancy without protein in the urine.[35]

Children

Causes

Primary hypertension

Hypertension results from a complex interaction of genes and environmental factors. Numerous common genetic variants with small effects on blood pressure have been identified[42] as well as some rare genetic variants with large effects on blood pressure.[43] Also, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 35 genetic loci related to blood pressure; 12 of these genetic loci influencing blood pressure were newly found.[44] Sentinel SNP for each new genetic locus identified has shown an association with DNA methylation at multiple nearby CpG sites. These sentinel SNP are located within genes related to vascular smooth muscle and renal function. DNA methylation might affect in some way linking common genetic variation to multiple phenotypes even though mechanisms underlying these associations are not understood. Single variant test performed in this study for the 35 sentinel SNP (known and new) showed that genetic variants singly or in aggregate contribute to risk of clinical phenotypes related to high blood pressure.[44]

Coronary artery ectasia: Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) is characterized by the enlargement of a coronary artery to 1.5 times or more than other non-ectasia parts of the vessel. The pooled unadjusted OR of CAE in subjects with Hypertension (HTN) in comparison by subjects without HTN was estimated 1.44.[45]

Blood pressure rises with

Events in early life, such as low birth weight, maternal smoking, and lack of breastfeeding may be risk factors for adult essential hypertension, although the mechanisms linking these exposures to adult hypertension remain unclear.[51] An increased rate of high blood uric acid has been found in untreated people with hypertension in comparison with people with normal blood pressure, although it is uncertain whether the former plays a causal role or is subsidiary to poor kidney function.[52] Average blood pressure may be higher in the winter than in the summer.[53] Periodontal disease is also associated with high blood pressure.[54]

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension results from an identifiable cause. Kidney disease is the most common secondary cause of hypertension.

A 2018 review found that any alcohol increased blood pressure in males while over one or two drinks increased the risk in females.[61]

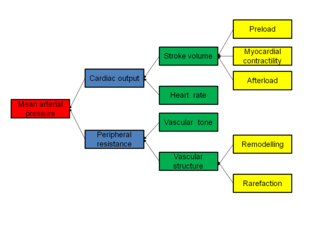

Pathophysiology

In most people with established

It is not clear whether or not

Many mechanisms have been proposed to account for the rise in peripheral resistance in hypertension. Most evidence implicates either disturbances in the kidneys' salt and water handling (particularly abnormalities in the intrarenal

Excessive sodium or insufficient potassium in the diet leads to excessive intracellular sodium, which contracts vascular smooth muscle, restricting blood flow and so increases blood pressure.[77][78]

Diagnosis

Hypertension is diagnosed on the basis of a persistently high resting blood pressure. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends at least three resting measurements on at least two separate health care visits.[79]

In Britain, 'Blood Pressure UK' states that a healthy blood pressure is any reading between 90/60mmHg and 120/80mmHg.[80]

Measurement technique

For an accurate diagnosis of hypertension to be made, it is essential for proper

With the availability of 24-hour

Other investigations

| System | Tests |

|---|---|

| Kidney | Microscopic urinalysis, protein in the urine, BUN, creatinine |

| Endocrine | Serum sodium, potassium, calcium, TSH |

Metabolic

|

triglycerides

|

| Other | electrocardiogram, chest radiograph

|

Once the diagnosis of hypertension has been made, healthcare providers should attempt to identify the underlying cause based on risk factors and other symptoms, if present.

Initial assessment of the hypertensive people should include a complete

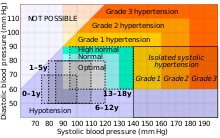

Classification in adults

| Categories | mmHg

|

And/or | Diastolic blood pressure , mmHg

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Office | 24h ambulatory | Office | 24h ambulatory | |

| Hypotension[94] | <110 | <100 | or | <70 | <60 |

| American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (2017)[95] | |||||

| Normal | <120 | <115 | and | <80 | <75 |

| Elevated | 120–129 | 115–124 | and | <80 | <75 |

| Hypertension, stage 1 | 130–139 | 125–129 | or | 80–89 | 75–79 |

| Hypertension, stage 2 | ≥140 | ≥130 | or | ≥90 | ≥80 |

| European Society of Hypertension (2023)[96] | |||||

| Optimal | <120 | — | and | <80 | — |

| Normal | 120–129 | — | and/or | 80–84 | — |

| High normal | 130–139 | — | and/or | 85–89 | — |

| Hypertension, grade 1 | 140–159 | ≥130 | and/or | 90–99 | ≥80 |

| Hypertension, grade 2 | 160–179 | — | and/or | 100–109 | — |

| Hypertension, grade 3 | ≥180 | — | and/or | ≥110 | — |

In people aged 18 years or older, hypertension is defined as either a systolic or a diastolic blood pressure measurement consistently higher than an accepted normal value (this is above 129 or 139 mmHg systolic, 89 mmHg diastolic depending on the guideline).[5][8] Lower thresholds are used if measurements are derived from 24-hour ambulatory or home monitoring.[95]

Children

Hypertension occurs in around 0.2 to 3% of newborns; however, blood pressure is not measured routinely in healthy newborns.

Hypertension defined as elevated blood pressure over several visits affects 1% to 5% of children and adolescents and is associated with long-term risks of ill-health.[97] Blood pressure rises with age in childhood and, in children, hypertension is defined as an average systolic or diastolic blood pressure on three or more occasions equal or higher than the 95th percentile appropriate for the sex, age and height of the child. High blood pressure must be confirmed on repeated visits however before characterizing a child as having hypertension.[97] Prehypertension in children has been defined as average systolic or diastolic blood pressure that is greater than or equal to the 90th percentile, but less than the 95th percentile.[97] In adolescents, it has been proposed that hypertension and pre-hypertension are diagnosed and classified using the same criteria as in adults.[97]

High blood pressure is frequently encountered in pediatric emergency and outpatient clinics, one of the simplest and reliable methods to assess the need for referral and or further action is the score developed by Elbaba M., published in 2018.[98] The score is composed of a set of 10 items with grades 1, 2 or 3 for each item. The author assumed the mid score of 15 or less is not associated with true hypertension, it can be reactive, white-coat or unreliable measurement. And the score of 16 or above reflects a warning alarm to true hypertension that usually require monitoring, investigations and or treatment.

Prevention

Much of the disease burden of high blood pressure is experienced by people who are not labeled as hypertensive.[99] Consequently, population strategies are required to reduce the consequences of high blood pressure and reduce the need for antihypertensive medications. Lifestyle changes are recommended to lower blood pressure, before starting medications. The 2004 British Hypertension Society guidelines[100] proposed lifestyle changes consistent with those outlined by the US National High BP Education Program in 2002[101] for the primary prevention of hypertension:

- maintain normal body weight for adults (e.g. body mass index 20–25 kg/m2)

- reduce dietary sodium intake to <100 mmol/ day (<6 g of sodium chloride or <2.4 g of sodium per day)

- engage in regular aerobic physical activity such as brisk walking (≥30 min per day, most days of the week)

- limit alcohol consumption to no more than 3 units/day in men and no more than 2 units/day in women

- consume a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (e.g. at least five portions per day);

- stress reduction[102]

Avoiding or learning to manage stress can help a person control blood pressure.

A few relaxation techniques that can help relieve stress are:

- meditation

- warm baths

- yoga

- going on long walks[102]

Effective lifestyle modification may lower blood pressure as much as an individual antihypertensive medication. Combinations of two or more lifestyle modifications can achieve even better results.

The value of routine screening for hypertension is debated.[106][107][108] In 2004, the National High Blood Pressure Education Program recommended that children aged 3 years and older have blood pressure measurement at least once at every health care visit[97] and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and American Academy of Pediatrics made a similar recommendation.[109] However, the American Academy of Family Physicians[110] supports the view of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that the available evidence is insufficient to determine the balance of benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents who do not have symptoms.[111][112] The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening adults 18 years or older for hypertension with office blood pressure measurement.[108][113]

Management

According to one review published in 2003, reduction of the

Target blood pressure

Various expert groups have produced guidelines regarding how low the blood pressure target should be when a person is treated for hypertension. These groups recommend a target below the range 140–160 / 90–100 mmHg for the general population.[14][15][115][116] Cochrane reviews recommend similar targets for subgroups such as people with diabetes[117] and people with prior cardiovascular disease.[118] Additionally, Cochrane reviews have found that for older individuals with moderate to high cardiovascular risk, the benefits of trying to achieve a lower than standard blood pressure target (at or below 140/90 mmHg) are outweighed by the risk associated with the intervention.[119] These findings may not be applicable to other populations.[119]

Many expert groups recommend a slightly higher target of 150/90 mmHg for those over somewhere between 60 and 80 years of age.[14][115][116][120] The JNC-8 and American College of Physicians recommend the target of 150/90 mmHg for those over 60 years of age,[15][121] but some experts within these groups disagree with this recommendation.[122] Some expert groups have also recommended slightly lower targets in those with diabetes[14] or chronic kidney disease with protein loss in the urine,[123] but others recommend the same target as for the general population.[15][117] The issue of what is the best target and whether targets should differ for high risk individuals is unresolved,[124] although some experts propose more intensive blood pressure lowering than advocated in some guidelines.[125]

For people who have never experienced cardiovascular disease who are at a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of less than 10%, the 2017 American Heart Association guidelines recommend medications if the systolic blood pressure is >140 mmHg or if the diastolic BP is >90 mmHg.[8] For people who have experienced cardiovascular disease or those who are at a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of greater than 10%, it recommends medications if the systolic blood pressure is >130 mmHg or if the diastolic BP is >80 mmHg.[8]

Lifestyle modifications

The first line of treatment for hypertension is lifestyle changes, including dietary changes, physical activity, and weight loss. Though these have all been recommended in scientific advisories,[126] a Cochrane systematic review found no evidence (due to lack of data) for effects of weight loss diets on death, long-term complications or adverse events in persons with hypertension.[127] The review did find a decrease in body weight and blood pressure.[127] Their potential effectiveness is similar to and at times exceeds a single medication.[14] If hypertension is high enough to justify immediate use of medications, lifestyle changes are still recommended in conjunction with medication.

Dietary changes shown to reduce blood pressure include diets with low sodium,[128][129] the DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension),[130] which was the best against 11 other diet in an umbrella review,[131] and plant-based diets.[132] There is some evidence green tea consumption may help lower blood pressure, but this is insufficient for it to be recommended as a treatment.[133] There is evidence from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials that Hibiscus tea consumption significantly reduces systolic blood pressure (-4.71 mmHg, 95% CI [-7.87, -1.55]) and diastolic blood pressure (−4.08 mmHg, 95% CI [-6.48, −1.67]).[134][135] Beetroot juice consumption also significantly lowers the blood pressure of people with high blood pressure.[136][137][138]

Increasing dietary potassium has a potential benefit for lowering the risk of hypertension.[139][140] The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) stated that potassium is one of the shortfall nutrients which is under-consumed in the United States.[141] However, people who take certain antihypertensive medications (such as ACE-inhibitors or ARBs) should not take potassium supplements or potassium-enriched salts due to the risk of high levels of potassium.[142]

Physical exercise regimens which are shown to reduce blood pressure include

Stress reduction techniques such as

Medications

Several classes of medications, collectively referred to as antihypertensive medications, are available for treating hypertension.

First-line medications for hypertension include

Previously,

The prescription of antihypertensive medication for children with hypertension has limited evidence. There is limited evidence which compare it with placebo and shows modest effect to blood pressure in short term. Administration of higher dose did not make the reduction of blood pressure greater.[152]

Resistant hypertension

Resistant hypertension is defined as high blood pressure that remains above a target level, in spite of being prescribed three or more antihypertensive drugs simultaneously with different mechanisms of action.[153] Failing to take prescribed medications as directed is an important cause of resistant hypertension.[154] Resistant hypertension may also result from chronically high activity of the autonomic nervous system, an effect known as neurogenic hypertension.[155] Electrical therapies that stimulate the baroreflex are being studied as an option for lowering blood pressure in people in this situation.[156]

Some common secondary causes of resistant hypertension include obstructive sleep apnea, pheochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and primary aldosteronism.[157] As many as one in five people with resistant hypertension have primary aldosteronism, which is a treatable and sometimes curable condition.[158]

Refractory hypertension

Refractory hypertension is characterized by uncontrolled elevated

Non-modulating

Non-modulating essential hypertension is a form of

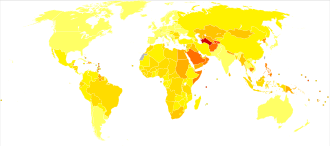

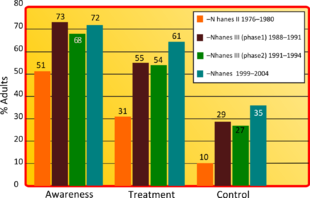

Epidemiology

| no data <110 110–220 220–330 330–440 440–550 550–660 | 660–770 770–880 880–990 990–1100 1100–1600 >1600 |

Adults

As of 2019[update], at least 1 billion 278 million adults aged 30–79 worldwide (over 16% of world population), including 626 million women and 652 million men, were estimated to have hypertension.[165] This is approximately 278 million up from 2014[166] and almost double compared to year 1990, when there were estimated 648 million adults in the same age group living with the condition worldwide.[165]

Hypertension is slightly more frequent in men,[165][166] in those of low socioeconomic status,[6] and it becomes more common with age.[6] It is common in high, medium, and low-income countries.[166][167] In 2004, rates of high blood pressure were highest in Africa (30% for both sexes), and lowest in the Americas (18% for both sexes). Rates also vary markedly within regions with country-level rates as low as 22.8% (men) and 18.4% (women) in Peru and as high as 61.6% (men) and 50.9% (women) in Paraguay.[165] Rates in Africa were about 45% in 2016.[168]

In Europe, hypertension occurs in about 30–45% of people as of 2013[update].

Children

Rates of high blood pressure in children and adolescents have increased in the last 20 years in the United States.[175] Childhood hypertension, particularly in pre-adolescents, is more often secondary to an underlying disorder than in adults. Kidney disease is the most common secondary cause of hypertension in children and adolescents. Nevertheless, primary or essential hypertension accounts for most cases.[176]

Prognosis

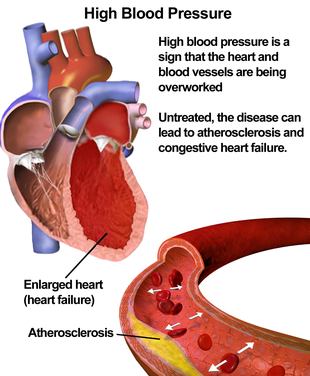

Hypertension is the most important

History

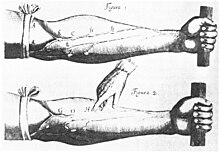

Measurement

Modern understanding of the cardiovascular system began with the work of physician

Identification

The symptoms similar to symptoms of patients with hypertensive crisis are discussed in medieval Persian medical texts in the chapter of "fullness disease".[183] The symptoms include headache, heaviness in the head, sluggish movements, general redness and warm to touch feel of the body, prominent, distended and tense vessels, fullness of the pulse, distension of the skin, coloured and dense urine, loss of appetite, weak eyesight, impairment of thinking, yawning, drowsiness, vascular rupture, and hemorrhagic stroke.[184] Fullness disease was presumed to be due to an excessive amount of blood within the blood vessels.

Descriptions of hypertension as a disease came among others from Thomas Young in 1808 and especially Richard Bright in 1836.[180] The first report of elevated blood pressure in a person without evidence of kidney disease was made by Frederick Akbar Mahomed (1849–1884).[185]

Until the 1990s, systolic hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or greater.[186] In 1993, the WHO/ISH guidelines defined 140 mmHg as the threshold for hypertension.[187]

Treatment

Historically the treatment for what was called the "hard pulse disease" consisted in reducing the quantity of blood by bloodletting or the application of leeches.[180] This was advocated by The Yellow Emperor of China, Cornelius Celsus, Galen, and Hippocrates.[180] The therapeutic approach for the treatment of hard pulse disease included changes in lifestyle (staying away from anger and sexual intercourse) and dietary program for patients (avoiding the consumption of wine, meat, and pastries, reducing the volume of food in a meal, maintaining a low-energy diet and the dietary usage of spinach and vinegar).

In the 19th and 20th centuries, before effective pharmacological treatment for hypertension became possible, three treatment modalities were used, all with numerous side-effects: strict sodium restriction (for example the rice diet[180]), sympathectomy (surgical ablation of parts of the sympathetic nervous system), and pyrogen therapy (injection of substances that caused a fever, indirectly reducing blood pressure).[180][188]

The first chemical for hypertension,

Society and culture

Awareness

Economics

High blood pressure is the most common chronic medical problem prompting visits to primary health care providers in US. The American Heart Association estimated the direct and indirect costs of high blood pressure in 2010 as $76.6 billion.

Other animals

Hypertension in cats is indicated with a systolic blood pressure greater than 150 mmHg, with amlodipine the usual first-line treatment. A cat with a systolic blood pressure above 170 mmHg is considered hypertensive. If a cat has other problems such as any kidney disease or retina detachment then a blood pressure below 160 mmHg may also need to be monitored.[197]

Normal blood pressure in dogs can differ substantially between breeds but hypertension is often diagnosed if systolic blood pressure is above 160 mmHg particularly if this is associated with target organ damage.[198] Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and calcium channel blockers are often used to treat hypertension in dogs, although other drugs may be indicated for specific conditions causing high blood pressure.[198]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e "High Blood Pressure Fact Sheet". CDC. 19 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ PMID 25795106.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-156437-3. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 August 2014.

- ^ S2CID 46601689.

- ^ S2CID 208792897.

- ^ PMID 10645931.

- PMID 29331891.

- ^ PMID 29133356.

- ^ a b c "How Is High Blood Pressure Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 10 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ S2CID 206028313.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-5249-1.

- ^ PMID 28784826.

- ^ "Hypertension". World Health Organization. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ PMID 23771844.

- ^ PMID 24352797.

- PMID 29459239.

- PMID 31167038.

- S2CID 46553658.

- from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- S2CID 42363250.

- PMID 28787537.

- PMID 28813123.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

- PMID 22777025.

- ^ S2CID 28579025.

- ^ "Truncal obesity (Concept Id: C4551560) – MedGen – NCBI". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4051-3061-5.

- ^ "High Blood Pressure – Understanding the Silent Killer". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 January 2021.

- S2CID 34137590.

- ^ "Hypertensive Crisis". heart.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ PMID 17565029. Archived from the originalon 4 December 2012.

- ^ PMID 14656957.

- ^ PMID 18254026.

- ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ^ a b "Management of hypertension in pregnant and postpartum women". uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- PMID 33870708.

- S2CID 265356623.

- PMID 37170819.

- ^ Gibson P (30 July 2009). "Hypertension and Pregnancy". eMedicine Obstetrics and Gynecology. Medscape. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ a b Rodriguez-Cruz E, Ettinger LM (6 April 2010). "Hypertension". eMedicine Pediatrics: Cardiac Disease and Critical Care Medicine. Medscape. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ S2CID 10698052.

- PMID 21909115.

- PMID 11239411.

- ^ PMID 26390057.

- PMID 34261539.

- PMID 11866648.

- S2CID 3231706. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- PMID 21880846.

- PMID 20937970.

- PMID 12364344.

- S2CID 10646150.

- PMID 32877573.

- PMID 24421749.

- PMID 31549149.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-6152-0.

- PMID 22195528.

- PMID 25816368.

- PMID 22138666.

- S2CID 32187480.

- PMID 20652462.

- PMID 29950485.

- PMID 6369352.

- ^ S2CID 11320300.

- S2CID 28992820.

- PMID 6461865.

- PMID 1291649.

- PMID 1735561.

- PMID 3301662.

- PMID 21845218.

- S2CID 42515260.

- PMID 15731494.

- PMID 21148349.

- S2CID 7685157.

- PMID 19630832.

- PMID 18579222.

- S2CID 13383731.

- S2CID 22345731.

- PMID 25398734.

- PMID 21771565.

- ^ "Blood Pressure UK". www.bloodpressureuk.org. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ PMID 28577621.

- ^ PMID 27417699.

- ^ PMID 26458123.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 102. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- PMID 22184330.

- PMID 19430163.

- ISBN 978-0-07-147691-1.

- PMID 19417858.

- PMID 18548142.

- PMID 17534459.

- PMID 16755312.

- PMID 16003448.

- PMID 16719248.

- PMID 27451950.

- ^ PMID 36100239.

- PMID 37345492.

- ^ PMID 15286277.

- ^ Elbaba M (2018). "NOVEL HYPERTENSION DIAGNOSTIC SCORE IN CHILDREN". Pediatric Nephrology. 33 (10): 1902–1903 – via 233 SPRING ST, NEW YORK, NY 10013 USA: SPRINGER.

- ^ PMID 14973512.

- PMID 15016698.

- S2CID 11071351.

- ^ a b "Hypertension: Causes, symptoms, and treatments". medicalnewstoday.com. 10 November 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ S2CID 205982690.

- S2CID 44581906.

The results showed that cardiovascular disease and death are increased with low sodium intake (compared with moderate intake) irrespective of hypertension status, whereas there is a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and death only in individuals with hypertension consuming more than 6 g of sodium per day (representing only 10% of the population studied)

- PMID 22555213.

- PMID 23303490.

- PMID 23303514.

- ^ PMID 32378196.

- PMID 22084329.

- ^ "Hypertension – Clinical Preventive Service Recommendation". Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- S2CID 20193715.

- ^ "Document | United States Preventive Services Taskforce". uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- S2CID 233409679.

- PMID 14604498.

- ^ PMID 25936483.

- ^ a b "Hypertension: Recommendations, Guidance and guidelines". NICE. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ PMID 24170669.

- PMID 36398903.

- ^ PMID 33332584.

- PMID 28135725.

- PMID 28135725.

- PMID 24424788.

- ^ "KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease" (PDF). Kidney International Supplements. December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2015.

- S2CID 44282689.

- PMID 27302266.

- ^ PMID 24243703.

- ^ PMID 33555049.

- S2CID 23522004.

- PMID 32094151.

- PMID 11136953.

- PMID 33022695.

- PMID 33281520.

- PMID 32028419.

- S2CID 210333560.

- PMID 20018807.

- ^ "Beetroot juice lowers high blood pressure, suggests research". British Heart Foundation.

- PMID 23596162.

- PMID 29141968.

- PMID 23558164.

- PMID 27455317.

- ^ "Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee". Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- PMID 21883995.

- ^ PMID 23608661.

- S2CID 20098894.

- PMID 18254065.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- PMID 29667175.

- S2CID 73993182.

- PMID 32026465.

- PMID 32519776.

- PMID 28107561.

- PMID 24488616.

- PMID 38372970.

- PMID 20724871.

- PMID 21536990.

- PMID 29136223.

- S2CID 8247941.

- S2CID 52824356.

- ^ PMID 30920924.

- PMID 27091893.

- PMID 3003304.

- ^ Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [page needed]

- ^ "Blood Pressure". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ S2CID 237286310.

- ^ a b c "Raised blood pressure". World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016.

- from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Oyedele D (20 February 2018). "Social divide". D+C, development and cooperation. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- S2CID 23660820.

- ^ PMID 7607734. Archived from the originalon 20 December 2012.

- S2CID 27522876.

- ^ PMID 20019324.

- ^ "Culture-Specific of Health Risk Health Status: Morbidity and Mortality". Stanford. 16 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- PMID 21911712.

- PMID 19421783.

- from the original on 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- S2CID 54363452.

- PMID 18375152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h

Esunge PM (October 1991). "From blood pressure to hypertension: the history of research". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 84 (10): 621. PMID 1744849.

- ^ PMID 21859967.

- ISBN 978-0-471-96788-0.

- PMID 25538828.

- PMID 25310615.

- ISBN 978-0-86542-861-4.

- PMID 3210285.

- PMID 8261554.

- ^ PMID 8823146.

- PMID 18899127.

- PMID 2685075.

- .

- ^ PMID 17534457.

- PMID 18548140.

- S2CID 31053059.

- S2CID 26799038.

- S2CID 8294060.

- PMID 28245741.

- ^ PMID 30353952.

Further reading

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. PMID 24352797.