Hyrax

| Hyraxes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) Erongo, Namibia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Superorder: | Afrotheria |

| Clade: | Paenungulatomorpha |

| Grandorder: | Paenungulata |

| Order: | Hyracoidea Huxley, 1869 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

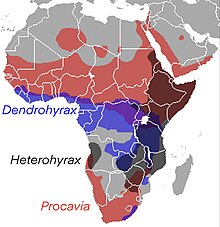

| The range map of Procaviidae, the only living family within Hyracoidea | |

Hyraxes (from

Hyraxes have a life span from 9 to 14 years. Six

Characteristics

Hyraxes retain or have redeveloped a number of primitive mammalian characteristics; in particular, they have poorly developed internal temperature regulation,[7] for which they compensate by behavioural thermoregulation, such as huddling together and basking in the sun.

Unlike most other browsing and grazing animals, they do not use the

Although not

The hyrax does not construct dens, as most rodents and rodent-like mammals do, but over the course of its lifetime rather seeks shelter in existing holes of great variety in size and configuration.[14]

Hyraxes inhabit rocky terrain across sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Their feet have rubbery pads with numerous sweat glands, which may help the animal maintain its grip when quickly moving up steep, rocky surfaces. Hyraxes have stumpy toes with hoof-like nails; four toes are on each front foot and three are on each back foot.[15] They also have efficient kidneys, retaining water so that they can better survive in arid environments.

Female hyraxes give birth to up to four young after a gestation period of 7–8 months, depending on the species. The young are weaned at 1–5 months of age, and reach sexual maturity at 16–17 months.

Hyraxes live in small family groups, with a single male that aggressively defends the territory from rivals. Where living space is abundant, the male may have sole access to multiple groups of females, each with its own range. The remaining males live solitary lives, often on the periphery of areas controlled by larger males, and mate only with younger females.[16]

Hyraxes have highly charged myoglobin, which has been inferred to reflect an aquatic ancestry.[17]

Similarities with Proboscidea and Sirenia

Hyraxes share several unusual characteristics with mammalian orders

Evolution

All modern hyraxes are members of the

Through the middle to late

The descendants of the giant "hyracoids" (common ancestors to the hyraxes, elephants, and sirenians) evolved in different ways. Some became smaller, and evolved to become the modern hyrax family. Others appear to have taken to the water (perhaps like the modern

Hyraxes are sometimes described as being the closest living relative of the elephant,[30] although whether this is so is disputed. Recent morphological- and molecular-based classifications reveal the sirenians to be the closest living relatives of elephants. While hyraxes are closely related, they form a taxonomic outgroup to the assemblage of elephants, sirenians, and the extinct orders Embrithopoda and Desmostylia.[31]

The extinct

List of genera

| Phylogeny of early hyracoids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A phylogeny of hyracoids known from the early Eocene through the middle Oligocene epoch.[33] |

- †Dimaitherium

- †Helioseus?

- †Microhyrax

- †Seggeurius

- †Geniohyidae

- †"Saghatheriidae" (Polyphyletic)

- †Titanohyracidae

- †Pliohyracidae

- Procaviidae

- Dendrohyrax(Tree hyrax)

- †Gigantohyrax

- Heterohyrax(Bush hyrax)

- Procavia (Rock hyrax)

Extant species

In the 2000s, taxonomists

The following cladogram shows the relationship between the extant genera:[38]

| Hyracoidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (order) |

Human interactions

Local and indigenous names

Biblical references

References are made to hyraxes in the

... hyraxes are creatures of little power, yet they make their home in the crags; ...

The words "rabbit", "hare", "coney", or "daman" appear as terms for the hyrax in some English translations of the Bible.[44][45] Early English translators had no knowledge of the hyrax, so no name for them, though "badger" or "rock-badger" has also been used more recently in new translations, especially in "common language" translations such as the Common English Bible (2011).[46]

"Spain"

One of the proposed etymologies for "Spain" is that it may be a derivation of the Phoenician I-Shpania, meaning "island of hyraxes", "land of hyraxes", but the Phoenecian-speaking Carthaginians are believed to have used this name to refer to rabbits, animals with which they were unfamiliar.[47] Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of Hadrian show a female figure with a rabbit at her feet,[48] and Strabo called it the "land of the rabbits".[49]

The Phoenician shpania is cognate to the modern Hebrew shafan.[50]

See also

References

- ^ "Hyracoidea" in Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Vol. 15: Mammals. Gale Publishing. Online version accessed April 2014.

- ^ "Dassie, n." Dictionary of South African English. Dictionary Unit for South African English, 2018. Web. 25 February 2019.

- ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-8061-7229-3.

- ^ a b "Eastern Tree Hyrax". IUCN red list. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Brown, Kelly Joanne (2003). "Seasonal Variation in the Thermal Biology of the Rock Hyrax (Proca Via Capensis)" (PDF). ukzn.ac.za. School of Botany and Zoology, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- .

- OCLC 251821046.]

All artiodactyl families and about 80% of the spp. were investigated. Chewing regurgitated fodder is an idle pastime, as well as an instinct associated with appetite. Characteristic movements were analyzed for undisturbed samples of animals maintained on preserves. Group-specific differences are reported in form, rhythm, frequency, and side of chewing motion. The ungulate type is characterized as a specialization. The operation is described for the first time for the order Hyracoidea. On the basis of 12 spp. of the marsupial subfamily Macropodinae rumination is inferred for the whole category. Advantages of the process are debated

[verification needed - PMID 8529006.

- ^ Sale, J. B. (1966). "Daily food consumption and mode of ingestion in the Hyrax". Journal of the East African Natural History Society. XXV (3): 219.

- ^ "Leviticus 11:5". Bible Gateway. Zondervan. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ Slifkin, Natan (11 March 2004). "Chapter Six – Shafan the Hyrax" (PDF). The Camel, the Hare, and the Hyrax. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ISSN 0044-5096.

- ^ "Hyrax". awf.org. African Wildlife Foundation.

- ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ^ "One Protein Shows Elephants and Moles Had Aquatic Ancestors". nationalgeographic.com. 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-77009-240-2.

- ^ Sisson, Septimus (1914). The anatomy of the domestic animals. W.B. Saunders Company. p. 577.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-7882-9.

- ^ "Dugong". gbrmpa.gov.au. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

- ^ Schrichte, David (7 June 2023). "Reproduction". SavetheManatee.org.

- ^ "Picture of hyrax feet".[dead link]

- S2CID 84398730.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34733-6.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-19-506039-3. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-8472-6. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ "Hyrax: The Little Brother of the Elephant". Wildlife on One. BBC TV.

- ^ "Hirax song is a menu for mating". The Economist. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- S2CID 39296485.

- ISBN 0-231-11013-8

- ISBN 978-0-8018-8022-3.

- S2CID 36591482.

- ^ Pickford, M.; Senut, B. (2018). "Afrohyrax namibensis (Hyracoidea, Mammalia) from the Early Miocene of Elisabethfeld and Fiskus, Sperrgebiet, Namibia" (PDF). Communications of the Geological Survey of Namibia. 18: 93–112.

- OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Barks in the night lead to the discovery of new species".

- ^ Pickford, M. (December 2005). "Fossil hyraxes (Hyracoidea: Mammalia) from the Late Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene of Africa, and the phylogeny of the Procaviidae". Palaeontologica Africana. 41: 141–161. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- .

- ^ "ترجمة و معنى hyrax في قاموس المعاني. قاموس عربي انجليزي". Almaany. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ ""Shaphan" in Strong's Concordance".

- OCLC 936245561.

- )

- )

- .

- )

- ^ "Rabbits, fish and mice, but no rock hyrax". Understanding Animal Research.

- hdl:2027/hvd.fl29jg.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ISBN 978-84-92807-80-2.

Hispania, the name that the Romans gave to the peninsular, derives from the Phoenician i-spn-ya, where the prefix i would translate as "coast", "island" or "land", ya as "region" and spn[,] in Hebrew saphan, as "rabbits" (in reality, hyraxes). The Romans, therefore, gave Hispania the meaning of "land abundant in rabbits", a use adopted by Cicero, Cesar, Pliny the Elder and, in particular, Catulo, who referred to Hispania as the cuniculus peninsula.

External links

Data related to Procaviidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Procaviidae at Wikispecies Media related to Hyracoidea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hyracoidea at Wikimedia Commons