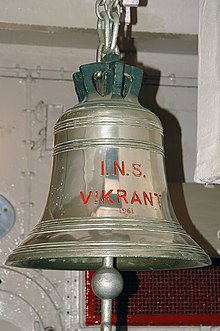

INS Vikrant (1961)

INS Vikrant in 1984

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Hercules |

| Builder | |

| Laid down | 14 October 1943 |

| Launched | 22 September 1945 |

| Commissioned | Never commissioned |

| Identification | Pennant number: R49 |

| Fate | Laid up , 1947; Sold to India, 1957 |

| Name | Vikrant |

| Acquired | 1957 |

| Commissioned | 4 March 1961 |

| Decommissioned | 31 January 1997 |

| Homeport | Bombay |

| Identification | Pennant number: R11 |

| Motto |

|

| Fate | Scrapped, 2014 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | light carrier |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 700 ft (210 m) ( o/a ) |

| Beam | 128 ft (39 m) |

| Draught | 24 ft (7.3 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 Parsons geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) |

| Range |

|

| Complement | 1,110 |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament | 16 × 40 mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns (later reduced to 8) |

| Aircraft carried | 21–23 |

| Aviation facilities |

|

In its later years, the ship underwent major refits to embark modern aircraft, before being

History and construction

In 1943 the

Sixteen light fleet carriers were ordered, and all were laid down as what became the Colossus class in 1942 and 1943. The final six ships were modified during construction to handle larger and faster aircraft, and were re-designated the Majestic class.[3] The improvements from the Colossus class to the Majestic class included heavier displacement, armament, catapult, aircraft lifts and aircraft capacity.[4] Construction on the ships was suspended at the end of World War II, as the ships were surplus to the Royal Navy's peacetime requirements. Instead, the carriers were modernized and sold to several

HMS Hercules, the fifth ship in the Majestic class, was ordered on 7 August 1942 and laid down on 14 October 1943 by

Design and description

Vikrant displaced 16,000 t (15,750 long tons) at

The ship was armed with sixteen 40-millimetre (1.6 in)

The ship was equipped with one LW-05 air-search radar, one ZW-06 surface-search radar, one LW-10 tactical radar and one Type 963 aircraft landing radar with other communication systems.[10]

Service

The Indian Navy's first aircraft carrier was

In December of that year, the ship was deployed for Operation Vijay (the code name for the

In June 1970, Vikrant was docked at the Naval Dockyard, Bombay, due to many internal fatigue cracks and fissures in the water drums of her boilers that could not be repaired by welding. As replacement drums were not available locally, four new ones were ordered from Britain, and Naval Headquarters issued orders not to use the boilers until further notice.[13] On 26 February 1971 the ship was moved from Ballard Pier Extension to the anchorage, without replacement drums. The main objective behind this move was to light up the boilers at reduced pressure, and work up the main and flight deck machinery that had been idle for almost seven months. On 1 March, the boilers were ignited, and basin trials up to 40 revolutions per minute (RPM) were conducted. Catapult trials were conducted on the same day.[14]

The ship began preliminary

...during the 1965 war Vikrant was sitting in Bombay Harbour and did not go out to sea. If the same thing happened in 1971, Vikrant would be called a white elephant and naval aviation would be written off. Vikrant had to be seen being operational even if we didn't fly any aircraft.

— Captain Gulab Mohanlal Hiranandani, [14]

Nanda and Hiranandani proved to be instrumental in taking Vikrant to war. There were objections that the ship might have severe operational difficulties that would expose the carrier to increased danger on operations. In addition, the three

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

As a part of preparations for the war, Vikrant was assigned to the

In the meantime, intelligence reports confirmed that Pakistan was to deploy a US-built Tench-class submarine, PNS Ghazi. Ghazi was considered as a serious threat to Vikrant by the Indian Navy, as Vikrant's approximate position would be known by the Pakistanis once she started operating aircraft. Of the four available surface ships, INS Kavaratti had no sonar, which meant that the other three had to remain in close vicinity 5–10 mi (8.0–16.1 km) of Vikrant, without which the carrier would be completely vulnerable to attack by Ghazi.[16]

On 23 July, Vikrant sailed off to

By the end of September, Vikrant and her escorts reached Port Blair. En route to Visakhapatnam, tactical exercises were conducted in the presence of the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Eastern Naval Command. From Vishakhapatnam, Vikrant set out for Madras for maintenance. Rear Admiral S. H. Sarma was appointed Flag Officer Commanding Eastern Fleet and arrived at Vishakhapatnam on 14 October. After receiving the reports that Pakistan might launch preemptive strikes, maintenance was stopped for another tactical exercise, which was completed during the night of 26–27 October at Vishakhapatnam. Vikrant then returned to Madras to resume maintenance. On 1 November, the Eastern Fleet was formally constituted, and on 13 November, all the ships set out for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. To avoid misadventures, it was planned to sail Vikrant to a remote anchorage, isolating it from combat. Simultaneously, deception signals would give the impression that Vikrant was operating somewhere between Madras and Vishakhapatnam.[18]

On 23 November, an emergency was declared in Pakistan after a clash of Indian and Pakistani troops in East Pakistan two days earlier.[18] On 2 December, the Eastern Fleet proceeded to its patrol area in anticipation of an attack by Pakistan. The Pakistan Navy had deployed Ghazi on 14 November with the explicit goal of targeting and sinking Vikrant, and Ghazi reached a location near Madras by the 23rd.[19][20] In an attempt to deceive the Pakistan Navy and Ghazi, India's Naval Headquarters deployed Rajput as a decoy—the ship sailed 160 mi (260 km) off the coast of Vishakhapatnam and broadcast a significant amount of radio traffic, making her appear to be Vikrant.[21]

Ghazi, meanwhile, sank off the Visakhapatnam coast under mysterious circumstances.[20] On the night of 3–4 December, a muffled underwater explosion was detected by a coastal battery. The next morning, a local fisherman observed flotsam near the coast, causing Indian naval officials to suspect a vessel had sunk off the coast. The next day, a clearance diving team was sent to search the area, and they confirmed that Ghazi had sunk in shallow waters.[22]

The reason for Ghazi's fate is unclear. The Indian Navy's official historian, Hiranandani, suggests three possibilities, after having analysed the position of the rudder and extent of the damage suffered. The first was that Ghazi had come up to periscope depth to identify her position and may have seen an anti-submarine vessel that caused her to crash dive, which in turn may have led her to bury her bow in the bottom. The second possibility is closely related to the first: on the night of the explosion, Rajput was on patrol off Visakhapatnam and observed a severe disturbance in the water. Suspecting that it was a submarine, the ship dropped two depth charges on the spot, on a position that was very close to the wreckage.[19] The third possibility is that there was a mishap when Ghazi was laying mines on the day before hostilities broke out.[22]

Vikrant was redeployed towards

Later years

Vikrant did not see much service after the war, and was given two major modernisation

Squadrons embarked

During her service, INS Vikrant embarked four squadrons of the Naval Air Arm of the Indian Navy:

| Squadron | Name | Insignia | Aircraft | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INAS 300 | White Tigers | Hawker Sea Hawk | Operated during the 1971 war, and phased out in 1978.[25] | |

BAE Sea Harrier |

Introduced in 1983, with the first Harrier landing on the ship's deck on 20 December 1983, operated until the ship was decommissioned in late 1997.[25][28] | |||

| INAS 310 | Cobras | Breguet Alizé |

Operated during the 1971 war, and phased out in 1987, with the last Alizé flown off on 2 April 1987.[25] | |

| INAS 321 | Angels | HAL Chetak[b] |

The Alouettes/Chetaks were first embarked in 1960s, and operated until the ship was decommissioned in 1997.[29] | |

| INAS 330 | Harpoons | Westland Sea King | Introduced into the Indian Navy in 1974,[30] the Sea Kings operated on Vikrant from 1991, and remained until the ship was decommissioned in 1997.[27] |

Commanding officers

| S.No | Name | Assumed office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Captain P. S. Mahindroo | 16 February 1961 | 16 April 1963 | Commisioning CO. Later Chief of Materiel. |

| 2 | Captain Nilakanta Krishnan DSC | 17 April 1963 | 16 November 1964 | Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 .

|

| 3 | Captain V. A. Kamath | 16 November 1964 | 4 November 1966 | Director General of Indian Coast Guard .

|

| 4 | Captain Jal Cursetji | 4 November 1966 | 8 December 1967 | Later Chief of the Naval Staff. |

| 5 | Captain E. C. Kuruvila | 8 December 1967 | 5 December 1969 | Flag Officer Commanding Southern Naval Area .

|

| 6 | Captain Kirpal Singh | 5 December 1969 | 15 January 1971 | Later Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet. |

| 7 | Captain S. L. Sethi NM

|

15 January 1971 | 30 June 1971 | Later Vice Chief of the Naval Staff. |

| 8 | Captain Swaraj Parkash MVC, AVSM | 1 July 1971 | 24 January 1973 | Later Director General of Indian Coast Guard .

|

| 9 | Captain M. K. Roy AVSM

|

3 January 1974 | 8 February 1976 | Later Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief Eastern Naval Command .

|

| 10 | Captain R. H. Tahiliani AVSM | 8 February 1976 | 26 December 1977 | Later Chief of the Naval Staff. |

| 11 | Captain J. C. Puri VrC, VSM | 26 December 1977 | 5 March 1979 | |

| 12 | Captain R. D. Dhir | 5 March 1979 | 15 June 1979 | |

| 13 | Captain S. Bose | 15 June 1979 | 2 April 1981 | |

| 14 | Captain A. Ghosh VSM | 2 April 1981 | 27 August 1982 | Later Fortress Commander Andaman and Nicobar Islands. |

| 15 | Captain NM

|

27 August 1982 | 19 November 1984 | Later Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief Western Naval Command .

|

| 16 | Captain NM

|

19 November 1984 | 17 March 1986 | |

| 17 | Captain P. A. Debrass NM

|

17 March 1986 | 8 August 1988 | Later Flag Officer Commanding Maharashtra Naval Area. |

| 18 | Captain B. S. Karpe | 11 October 1988 | 22 October 1989 | |

| 19 | Captain R. N. Ganesh NM

|

22 October 1989 | 3 January 1991 | Later Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief Southern Naval Command .

|

| 20 | Captain Raman Puri VSM | 3 January 1991 | 25 June 1992 | Later Chief of Integrated Defence Staff. |

| 21 | Captain R. C. Kochchar VSM | 25 June 1992 | 7 September 1994 | Later Flag Officer Commanding Maharashtra Naval Area. |

| 22 | Captain K. Mohanan | 7 September 1994 | 7 August 1995 | |

| 23 | Commander H. S. Rawat | 20 July 1996 | 31 January 1997 |

Museum ship

Following decommissioning in 1997, the ship was earmarked for preservation as a museum ship in Mumbai. Lack of funding prevented progress on the ship's conversion to a museum and it was speculated that the ship would be made into a training ship.[31] In 2001, the ship was opened to the public by the Indian Navy, but the Government of Maharashtra was unable to find a partner to operate the museum on a permanent, long-term basis and the museum was closed after it was deemed unsafe for the public in 2012.[32][33]

Scrapping

In August 2013,

In January 2014, the ship was sold through an online auction to a Darukhana ship-breaker for ₹60 crore (US$7.5 million).[38][39][40] The Supreme Court of India dismissed another lawsuit challenging the ship's sale and scrapping on 14 August 2014.[41] Vikrant remained beached off Darukhana in Mumbai Port while awaiting the final clearances of the Mumbai Port Trust. On 12 November 2014, the Supreme Court gave its final approval for the carrier to be scrapped, which commenced on 22 November 2014.[42]

On 7 April 2022, an FIR against an ex-MP Kirit Somaiya, his son Neil, and others was registered, on charges of alleged cheating and criminal breach of trust linked to the collection of funds up to Rs. 57 crore for restoring the decommissioned aircraft carrier INS Vikrant. The Trombay Police booked them under Section 420 (cheating and dishonesty including delivery of property) and Section 406 (punishment for criminal breach of trust) and Section 34 (common intentions) of the Indian Penal Code.

According to the complaint, the father and son duo collected the money in 2013-14 in the name of restoring Vikrant, but the funds collected were spent on personal use.

Somaiya was leading the front of attacking the government's intent of commercializing the decommissioned ship by handing it to private players.[43]

Legacy

In memory of Vikrant, the Vikrant Memorial was unveiled by Vice Admiral Surinder Pal Singh Cheema, Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Western Naval Command at K Subash Marg in the Naval Dockyard of Mumbai on 25 January 2016. The memorial is made from metal recovered from the ship.[44] In February 2016, the Indian automobile manufacturer Bajaj unveiled a new motorbike made with metal from Vikrant's scrap and named it Bajaj V in honour of the Vikrant.[11][45]

The navy has named its first home-built carrier

In popular culture

The decommissioned ship featured prominently in the film ABCD 2 as a backdrop while it was moored near Darukhana in Mumbai.[48]

See also

Footnotes

References

- ^ a b "HMS Hercules". Fleet Air Arm Archive. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Konstam 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Hobbs 2014, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Hobbs 2014, p. 185.

- ^ Hobbs 2014, p. 199.

- ^ a b c "INS Vikrant R11". www.bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hobbs 2014, p. 203.

- ^ Chant 2014, p. 187.

- ^ a b "Bajaj V – A bike made of INS Vikrant's metal – Launching on February 1". The Financial Express. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Brigadier A. S. Cheema. "Operation Vijay: The Liberation of 'Estado da India' – Goa, Daman and Diu". USI of India. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2000, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d Hiranandani 2000, p. 119.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2000, p. 120.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Hiranandani 2000, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Hiranandani 2000, p. 123.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2000, p. 143.

- ^ a b c Till 2013, p. 171.

- ^ Hiranandani 2000, p. 142.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2000, p. 145.

- ^ Roy 1995, p. 165.

- ^ Hiranandani 2000, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hiranandani 2009, p. 151.

- ^ Hiranandani 2000, p. 276.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2009, p. 152.

- ^ Hiranandani 2009, p. 154.

- ^ a b Hiranandani 2009, p. 158.

- ^ Hiranandani 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Sanjai, P R (14 March 2006). "INS Vikrant will now be made training school". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ Sunavala, Nargish (4 February 2006). "Not museum but scrapyard for INS Vikrant". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Warship INS Vikrant heads for Alang death". Times of India. 30 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Naik, Yogesh (10 August 2013). "Vikrant museum to be scrapped as Navy readies new carrier". Mumbai Mirror. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "Govt to auction decommissioned aircraft carrier INS Vikrant". First Post India. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Sunavala, Nargish (3 February 2014). "Not museum but scrapyard for INS Vikrant". Times of India. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2006.

- ^ "Crushing museum dreams, court says INS Vikrant must be scrapped". Mumbai Mirror. 24 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Indian Express. 21 November 2014. Archivedfrom the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "India's first aircraft carrier slips into history | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 22 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Not museum but scrapyard for warship Vikrant". Times of India. 3 February 2014. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Activists move Supreme Court over Sale of INS Vikrant to Ship Breaker". Bihar Prabha. 14 August 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "India's first aircraft carrier slips into history". Times of India. 22 November 2014. Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Shaikh, Zeeshan (8 April 2022). "Explained: The cheating case related to INS Vikrant in which BJP's Kirit Somaiya, son have been booked". The Indian Express.

- ^ "Vikrant Memorial at traffic Island near Lion Gate". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Bajaj V: A Bike Made with INS Vikrant's Scrap unveiled". eHot News. 2 February 2015. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Comparison of Chinese Aircraft Carrier Liaoning and Indian INS Vikrant". The World Reporter. 25 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Varun poses before INS Vikrant". Bollywood Bazaar. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

Bibliography

- Chant, Christopher (2014), A Compendium of Armaments and Military Hardware, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-64668-5

- ISBN 978-1-897829-72-1

- Hiranandani, Gulab Mohanlal (2009), Transition to Guardianship: The Indian Navy, 1991–2000, Lancer Publishers LLC, ISBN 978-1-935501-66-4

- Hobbs, David (2014), British Aircraft Carriers: Design, Development & Service Histories, Seaforth Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4738-5369-0

- Konstam, Angus (2012), The Aviation History, Books on Demand, ISBN 978-3-8482-6639-5

- Roy, Mihir K. (1995), War in the Indian Ocean, Lancer Publishers, ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0

- Till, Geoffrey (2013), Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-25555-7

External links

- Mission Vikrant 1971: A search for our heroes Archived 10 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Sons of Vikrant by Bajaj