Ibn al-Jawzi

Ibn al-Jawzi | |

|---|---|

school of jurisprudence | |

| Major shrine | Green Cement Tomb at Baghdad, Iraq |

Ibn al-Jawzi | |

|---|---|

| Title | Hanbali |

| Main interest(s) | History, Tafsir, Hadith, Fiqh |

| Notable work(s) | Daf' Shubah al-Tashbih |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced

| |

Abū al-Farash ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Jawzī,

Ibn al-Jawzi received a "very thorough education"

Life

Ibn al-Jawzi was born between 507 and 12 H./1113-19 CE to a "fairly wealthy family"

Ibn al-Jawzi began his career proper during the reign of

During the reign of the succeeding Abbasid caliph, al-Mustadi (d. 1180), Ibn al-Jawzi began to be recognized "as one of the most influential persons in Baghdad."[10] As this particular ruler was especially partial to Hanbalism,[10] Ibn al-Jawzi was given free rein to promote Hanbalism by way of his preaching throughout Baghdad.[10] The numerous sermons Ibn al-Jawzi delivered from 1172 to 1173 cemented his reputation as the premier scholar in Baghdad at the time; indeed, the scholar soon began to be so appreciated for his gifts as an orator that al-Mustadi even went so far as to have a special dais (Arabic dikka) constructed specially for Ibn al-Jawzi in the Palace mosque.[10] Ibn al-Jawzi's stature as a scholar only continued to grow in the following years.[10]

By 1179, Ibn al-Jawzi had written over one hundred and fifty works and was directing five colleges in Baghdad simultaneously.

Views and thought

Polemics

Ibn al-Jawzi was a noted

Relics

Ibn al-Jawzi was an avid supporter of using the

Saints

Ibn al-Jawzi supported the orthodox and widespread classical belief in the existence of

The saints and the righteous are the very purpose of all that exists (al-awliya wa-al-salihun hum al-maqsud min al-kawn): they are those who learned and practiced with the reality of knowledge... Those who practice what they know, do with little in the world, seek the next world, remain ready to leave from one to the other with wakeful eyes and good provision, as opposed to those renowned purely for their knowledge."[17]

Sufism

Ibn al-Jawzi evidently held that

Creed

| Part of a series on |

| Ash'arism |

|---|

|

| Background |

Theology

Ibn al-Jawzi is famous for the theological stance that he took against other Hanbalites of the time, in particular Ibn al-Zaghuni and al-Qadi Abu Ya'la. He believed that these and other Hanbalites had gone to extremes in affirming God's Attributes, so much so that he accused them of tarnishing the reputation of Hanbalites and making it synonymous with extreme anthropomorphism (likening God to his creation). Ibn al-Jawzi stated that,

"They believed that He has a form and a face in addition to His Self. They believed that He has two eyes, a mouth, a uvula and molars, a face which is light and splendor, two hands, including the palms of hands, fingers including the little fingers and the thumbs, a back, and two legs divided into thighs and shanks."[20]

And he continued his attack on Abu Ya'la by stating that, "Whoever confirms that God has molars as a divine attribute, has absolutely no knowledge of Islam."[21]

Ibn al-Jawzi's most famous work in this regard is his

God is neither inside nor outside the Universe

Ibn Jawzi states, in As-Sifat, that God neither exists inside the world nor outside of it.[22] To him, "being inside or outside are concomitant of things located in space" i.e. what is outside or inside must be in a place, and, according to him, this is not applicable to God.[22] He writes:

Both [being in a place and outside a place] along with movement, rest, and other accidents are constitutive of bodies ... The divine essence does not admit of any created entity [e.g. place] within it or inhering in it.[22]

Works

Ibn al-Jawzi is perhaps the most prolific author in Islamic history. Al-Dhahabi states: "I have not known anyone amongst the 'ulama to have written as much as he (Ibn al-Jawzi) did.[2] Recently, Professor Abdul Hameed al-Aloojee, an Iraqi scholar conducted research on the extent of ibn al Jawzi's works and wrote a reference work in which he listed Ibn al Jawzees's works alphabetically, identifying the publishers and libraries where his unpublished manuscripts could be found. Some have suggested that he is the author of more than 700 works.[4]

In addition to the topic of religion, Ibn al-Jawzi wrote about medicine as well. Like the medicinal works of Al-Suyuti, Ibn al-Jawzi's book was almost exclusively based on Prophetic medicine rather than a synthesis of both Islamic and Greek medicine like the works of Al-Dhahabi. Ibn al-Jawzi's work focused primarily on diet and natural remedies for both serious ailments such as rabies and smallpox and simple conditions such as headaches and nosebleeds.[23]

- A Great Collection of Fabricated Traditions

- Daf' Shubah al-Tashbih[24]

- Sifatu al-Safwah, five parts, reworking of Hilyat al-Awliya by the 11th century scholar Abu Nu'aym al-Isfahani

- 'Ādāb al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī wa-Zuhduh wa-Mawaʿiẓuh (The Manners of Hasan al-Basri, his Asceticism, and his Exhortations)[25]

- Zad al-Masir fi Ilm al-Tafsir [26]

- Talbīs Iblīs

- Tadhkirah Uli Al-Basāir fī Ma'rifah Al-Kabāir

- Gharīb Al-Ḥadīth

- Ahkam Al-Nisa

- Hifdh Al-'Umr

- Bahr Al-Damou'

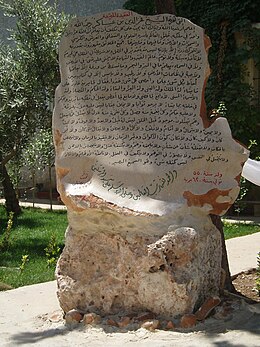

Tomb

The tomb of Ibn Al-Jawzi is located at Baghdad, Iraq. The tomb is a simple green cement slab surrounded by rocks, and a paper sign on it indicating it is the tomb. In 2019 rumors spread about the tomb being removed after a photo was released showing the removal of the tomb. However, the Iraqi officials denied it.[27]

See also

- Sibt ibn al-Jawzi

- Ibn 'Aqil

- Notable Hanbali Scholars

- List of Muslim historians

- Asad Mayhani

References

- ^ Al-Dhahabi, Siyar A'lam al-Nubala'.

- ^ a b c "IslamicAwakening.Com: Ibn al-Jawzi: A Lifetime of Da'wah". October 22, 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-10-22.

- ^ Robinson:2003:XV

- ^ a b "Ibn Al-Jawzi". Sunnah.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Laoust, H., "Ibn al-D̲j̲awzī", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ a b Ibn Rajab, Dhayl ʿalā Ṭabaqāt al-ḥanābila, Cairo 1372/1953, i, 401

- ^ a b c d Ibn Rajab, Dhayl ʿalā Ṭabaqāt al-ḥanābila, Cairo 1372/1953, i, 404–405

- ^ Ibn al-Jawzi, Sincere Counsel to the Seekers of Sacred Knowledge, Daar Us-Sunnah Publications Birmingham (2011), p. 88

- ^ Ibn Rajab, Dhayl ʿalā Ṭabaqāt al-ḥanābila, Cairo 1372/1953, i, 399–434;Merlin Swartz, Ibn al-Jawzī’s Kitāb al-Quṣṣāṣ wa-’l-mudhakkirīn, Recherches publiées sous la direction de l’Institut de lettres orientales de Beyrouth, Série 1, Pensée arabe et musulmane, 47 (Beirut: Dar el-Machreq, 1971), 15.

- ^ OCLC 495469525.

- ^ a b c Boyle, J.A. (January 1, 1968). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods (Volume 5). Cambridge University Press. p. 299.

Talbis Iblis, by the Ash'ari theologian Ibn al-Jawzi, contains strong attacks on the Sufis, though the author makes a distinction between an older purer Sufism and the "modern" one,

- ^ Ibn Rajab, Dhayl ʿalā Ṭabaqāt al-ḥanābila, Cairo 1372/1953, i, 404

- ^ Ibn Rajab, Dhayl ʿalā Ṭabaqāt al-ḥanābila, Cairo 1372/1953, i, 402

- ^ Ibn Kat̲h̲īr, Bidāya, Cairo 1351-8/1932-9, xii, 28–30

- ^ a b Ibn al-Jawzī, The Life of Ibn Hanbal, XXIV.2, trans. Michael Cooperson (New York: New York University Press, 2016), p. 89

- ^ Jonathan A. C. Brown, "Faithful Dissenters: Sunni Skepticism about the Miracles of Saints," Journal of Sufi Studies 1 (2012), p. 162

- ^ Ibn al-Jawzi, Sifat al-safwa (Beirut ed. 1989/1409) p. 13, 17.

- ^ a b c d e "Error404".

- ^ Ibn al-Ahdal (1964). Ahmad Bakīr Mahmud (ed.). Kashf al-Ghata' 'an Haqa'iq al-Tawhid كشف الغطاء عن حقائق التوحيد (PDF) (in Arabic). Tunisia: Tunisian General Labour Union. p. 83.

وكل هؤلاء الذين ذكرنا عقائدهم من أئمة الشافعية سوى القرشي والشاذلي فمالكيان أشعريان. ولنتبع ذلك بعقيدة المالكية وعقيدتين للحنفية ليعلم أن غالب أهل هذين المذهبين على مذهب الأشعري في العقائد، وبعض الحنبلية في الفروع يكونون على مذهب الأشعري في العقائد كالشيخ عبد القادر الجيلاني وابن الجوزي وغيرهما رضي الله عنهم. وقد تقدم وسيأتي أيضاً أن الأشعري والإمام أحمد كانا في الاعتقاد متفقين حتى حدث الخلاف من أتباعه القائلين بالحرف والصوت والجهة وغير ذلك فلهذا لم نذكر عقائد المخالفين واقتصرنا على عقائد أصحابنا الأشعرية ومن وافقهم من المالكية والحنفية رضي الله عنهم. فأما عقيدة المالكية فهي تأليف الشيخ الإمام الكبير الشهير أبي محمد عبد الله بن أبي زيد المالكي ذكرها في صدر كتابه الرسالة

- ^ a b Holtzman, Livnat. ""Does God Really Laugh?" – Appropriate and Inappropriate Descriptions of God in Islamic Traditionalist Theology" (PDF). Bar‐Ilan University, Ramat Gan. p. 188.

- ^ Holtzman, Livnat. ""Does God Really Laugh?" – Appropriate and Inappropriate Descriptions of God in Islamic Traditionalist Theology" (PDF). Bar‐Ilan University, Ramat Gan. p. 191.

- ^ a b c Swartz, Merlin. A Medieval Critique of Anthropomorphism, pg. 159. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2001.

- ISBN 0-415-12412-3

- ^ Swartz, Merlin. A Medieval Critque of Anthropomorphism. Brill, 2001

- OCLC 4770455870.

- ^ "Zad al-Masir fi Ilm al-Tafsir 8 vol.4 books".

- ^ "شفق نيوز". شفق نيوز.

References

- Robinson, Chase F. (2003), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62936-5

External links

- Biodata at MuslimScholars.info

- The Attributes of God 'Abd al-Rahman ibn al-Jawzi trans. Abdullah bin Hamid 'Ali published by Amal Press

- The Most Comprehensive Biographical Note of Ibn al-Jawzi online

- (in French) Importance of attachment to the Qur'an by Imam Ibn Al Jawzi

- (in French) Refutation of anthropomorphism by Imam Ibn Al Jawzi