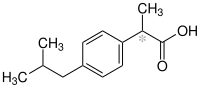

Ibuprofen

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈaɪbjuːproʊfɛn/, /aɪbjuːˈproʊfən/, EYE-bew-PROH-fən |

| Trade names | Advil, Motrin, Nurofen, others |

| Other names | isobutylphenylpropionic acid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682159 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

topical, intravenous | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80–100% (orally),[4] 87% (rectal) |

| Protein binding | 98%[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C9)[5] |

| Metabolites | ibuprofen glucuronide, 2-hydroxyibuprofen, 3-hydroxyibuprofen, carboxy-ibuprofen, 1-hydroxyibuprofen |

| Onset of action | 30 min[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 2–4 h[7] |

| Excretion | Urine (95%)[5][8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Density | 1.03 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 75 to 78 °C (167 to 172 °F) |

| Boiling point | 157 °C (315 °F) at 4 mmHg |

| Solubility in water | 0.021 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ibuprofen is a

Common

Ibuprofen was discovered in 1961 by

Medical uses

Ibuprofen is used primarily to treat

It is used for inflammatory diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.[20][21] It is also used for pericarditis and patent ductus arteriosus.[3][22][23]

Ibuprofen lysine

In some countries, ibuprofen lysine (the lysine salt of ibuprofen, sometimes called "ibuprofen lysinate") is licensed for treatment of the same conditions as ibuprofen; the lysine salt is used because it is more water-soluble.[24]

Ibuprofen lysine is sold for rapid pain relief;[25] given in the form of its lysine salt, absorption is much quicker (35 minutes for the salt compared to 90–120 minutes for ibuprofen). However, a clinical trial with 351 participants in 2020, funded by Sanofi, found no significant difference between ibuprofen and ibuprofen lysine concerning the eventual onset of action or analgesic efficacy.[26][unreliable medical source]

In 2006, ibuprofen lysine was approved in the US by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for closure of patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants weighing between 500 and 1,500 g (1 and 3 lb), who are no more than 32 weeks gestational age when usual medical management (such as fluid restriction, diuretics, and respiratory support) is not effective.[27]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects include

Infrequent adverse effects include esophageal ulceration,

Allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis and anaphylactic shock, may occur.[30] Ibuprofen may be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to demonstrate the presence of the drug in a person having experienced an anaphylactic reaction, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in people who are hospitalized, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. A monograph relating ibuprofen plasma concentration, time since ingestion, and risk of developing renal toxicity in people who have overdosed has been published.[31]

In October 2020, the US FDA required the drug label to be updated for all NSAID medications to describe the risk of kidney problems in unborn babies that result in low amniotic fluid.[32][33]

Cardiovascular risk

Along with several other NSAIDs, chronic ibuprofen use has been found correlated with risk of progression to

Skin

Along with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen has been associated with the onset of

Interactions

Alcohol

Drinking alcohol when taking ibuprofen may increase the risk of

Aspirin

According to the FDA, "ibuprofen can interfere with the

Paracetamol

Ibuprofen combined with paracetamol is considered generally safe in children for short-term usage.[46]

Overdose

Ibuprofen overdose has become common since it was licensed for

The severity of symptoms varies with the ingested dose and the time elapsed; however, individual sensitivity also plays an important role. Generally, the symptoms observed with an overdose of ibuprofen are similar to the symptoms caused by overdoses of other NSAIDs.Correlation between severity of symptoms and measured ibuprofen plasma levels is weak. Toxic effects are unlikely at doses below 100 mg/kg, but can be severe above 400 mg/kg (around 150 tablets of 200 mg units for an average man);[49] however, large doses do not indicate the clinical course is likely to be lethal.[50] A precise lethal dose is difficult to determine, as it may vary with age, weight, and concomitant conditions of the individual person.

Treatment to address an ibuprofen overdose is based on how the symptoms present. In cases presenting early, decontamination of the stomach is recommended. This is achieved using

Miscarriage

A Canadian study of pregnant women suggests that those taking any type or amount of NSAIDs (including ibuprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen) were 2.4 times more likely to miscarry than those not taking the medications.[53] However, an Israeli study found no increased risk of miscarriage in the group of mothers using NSAIDs.[54]

Pharmacology

NSAIDs such as ibuprofen work by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which convert arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). PGH2, in turn, is converted by other enzymes to several other prostaglandins (which are mediators of pain, inflammation, and fever) and to thromboxane A2 (which stimulates platelet aggregation, leading to the formation of blood clots).

Like aspirin and

Ibuprofen is administered as a racemic mixture. The R-enantiomer undergoes extensive interconversion to the S-enantiomer in vivo. The S-enantiomer is believed to be the more pharmacologically active enantiomer.[57] The R-enantiomer is converted through a series of three main enzymes. These enzymes include acyl-CoA-synthetase, which converts the R-enantiomer to (−)-R-ibuprofen I-CoA; 2-arylpropionyl-CoA epimerase, which converts (−)-R-ibuprofen I-CoA to (+)-S-ibuprofen I-CoA; and hydrolase, which converts (+)-S-ibuprofen I-CoA to the S-enantiomer.[43] In addition to the conversion of ibuprofen to the S-enantiomer, the body can metabolize ibuprofen to several other compounds, including numerous hydroxyl, carboxyl and glucuronyl metabolites. Virtually all of these have no pharmacological effects.[43]

Unlike most other NSAIDs, ibuprofen also acts as an inhibitor of Rho kinase and may be useful in recovery from spinal-cord injury.[58][59] Another unusual activity is inhibition of the sweet taste receptor.[60]

Pharmacokinetics

After oral administration, peak serum concentration is reached after 1–2 hours, and up to 99% of the drug is bound to plasma proteins.[61] The majority of ibuprofen is metabolized and eliminated within 24 hours in the urine; however, 1% of the unchanged drug is removed through biliary excretion.[57]

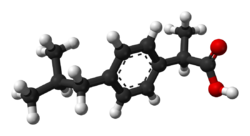

Chemistry

Ibuprofen is practically insoluble in water, but very soluble in most organic solvents like ethanol (66.18 g/100 mL at 40 °C for 90% EtOH), methanol, acetone and dichloromethane.[62]

The original synthesis of ibuprofen by the Boots Group started with the compound isobutylbenzene. The synthesis took six steps. A modern, greener technique with fewer waste byproducts for the synthesis involves only three steps was developed in the 1980s by the Celanese Chemical Company.[63][64] The synthesis is initiated with the acylation of isobutylbenzene using the recyclable Lewis acid catalyst hydrogen fluoride.[65][66] The following catalytic hydrogenation of isobutylacetophenone is performed with either Raney nickel or palladium on carbon to lead into the key-step, the carbonylation of 1-(4-isobutylphenyl)ethanol. This is achieved by a PdCl2(PPh3)2 catalyst, at around 50 bar of CO pressure, in the presence of HCl (10%).[67] The reaction presumably proceeds through the intermediacy of the styrene derivative (acidic elimination of the alcohol) and (1-chloroethyl)benzene derivative (Markovnikow addition of HCl to the double bond).[68]

Stereochemistry

Ibuprofen, like other 2-arylpropionate derivatives such as ketoprofen, flurbiprofen and naproxen, contains a stereocenter in the α-position of the propionate moiety.

|

|

|

|

| (R)-ibuprofen | (S)-ibuprofen |

The product sold in pharmacies is a racemic mixture of the S and R-isomers. The S (dextrorotatory) isomer is the more biologically active; this isomer has been isolated and used medically (see dexibuprofen for details).[62]

The isomerase enzyme, alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase, converts (R)-ibuprofen into the (S)-enantiomer.[69][70][71]

(S)-ibuprofen, the

History

Ibuprofen was derived from

The medication was launched as a treatment for

In November 2013, work on ibuprofen was recognized by the erection of a Royal Society of Chemistry blue plaque at Boots' Beeston Factory site in Nottingham,[81] which reads:

In recognition of the work during the 1980s by The Boots Company PLC on the development of ibuprofen which resulted in its move from prescription only status to over the counter sale, therefore expanding its use to millions of people worldwide

and another at BioCity Nottingham, the site of the original laboratory,[81] which reads:

In recognition of the pioneering research work, here on Pennyfoot Street, by Dr Stewart Adams and Dr John Nicholson in the Research Department of Boots which led to the discovery of ibuprofen used by millions worldwide for the relief of pain.

Availability and administration

Ibuprofen was made available by prescription in the United Kingdom in 1969 and in the United States in 1974.[82]

Ibuprofen is the International nonproprietary name (INN), British Approved Name (BAN), Australian Approved Name (AAN) and United States Adopted Name (USAN). In the United States, it has been sold under the brand-names Motrin and Advil since 1974[83] and 1984,[84] respectively. Ibuprofen is commonly available in the United States up to the FDA's 1984 dose limit OTC, rarely used higher by prescription.[85][failed verification]

In 2009, the first injectable formulation of ibuprofen was approved in the United States, under the brand name Caldolor.[86][87]

Ibuprofen can be taken orally (by mouth) (as a tablet, a capsule, or a suspension) and intravenously.[9]

Research

Ibuprofen is sometimes used for the treatment of acne because of its anti-inflammatory properties, and has been sold in Japan in topical form for adult acne.[88][89] As with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen may be useful in the treatment of severe orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure when standing up).[90] NSAIDs are of unclear utility in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease.[91][92]

Ibuprofen has been associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease and may delay or prevent it. Aspirin, other NSAIDs, and paracetamol (acetaminophen) had no effect on the risk for Parkinson's.[93] In March 2011, researchers at Harvard Medical School announced in Neurology that ibuprofen had a neuroprotective effect against the risk of developing Parkinson's disease.[94][95][96] People regularly consuming ibuprofen were reported to have a 38% lower risk of developing Parkinson's disease, but no such effect was found for other pain relievers, such as aspirin and paracetamol. Use of ibuprofen to lower the risk of Parkinson's disease in the general population would not be problem-free, given the possibility of adverse effects on the urinary and digestive systems.[97]

Some

References

- ^ Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Pedea EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 29 July 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- S2CID 17144030.

- ^ S2CID 1186212.

- ^ "ibuprofen". Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- PMID 28651847.

- ^ "Brufen Tablets And Syrup" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Ibuprofen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0857110862.

- ^ "Ibuprofen Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Kindy D. "The Inventor of Ibuprofen Tested the Drug on His Own Hangover". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

Stewart Adams and his associate John Nicholson invented a pharmaceutical drug known as 2-(4-isobutylphenyl) propionic acid.

- ^ S2CID 26344532.

- ^ "Chemistry in your cupboard: Nurofen". RSC Education. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Ibuprofen. Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "10.1.1 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". British National Formulary. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- PMID 11996413.

- ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- PMID 25164988.

- PMID 27197952.

- PMID 12723741.

- S2CID 592438.

- PMID 31912434.

- PMID 20718179.

- PMID 23137151.

- S2CID 38589434.

- PMID 31993263.

- Foster City, USA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 758–761.

- ^ "FDA Warns that Using a Type of Pain and Fever Medication in Second Half of Pregnancy Could Lead to Complications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NSAIDs may cause rare kidney problems in unborn babies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- PMID 16103274.

- PMID 15947398.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA strengthens warning that non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause heart attacks or strokes". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 9 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "Ibuprofen- and dexibuprofen-containing medicines". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 22 May 2015. EMA/325007/2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "High-dose ibuprofen (≥2400mg/day): small increase in cardiovascular risk". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ Chan LS (12 June 2014). Hall R, Vinson RP, Nunley JR, Gelfand JM, Elston DM (eds.). "Bullous Pemphigoid Clinical Presentation". Medscape Reference. United States: WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011.

- PMID 1531054.

- PMID 18193504.

- PMID 20101062.

- ^ a b c Rainsford KD (2012). Ibuprofen: Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Side Effects. London: Springer.

- ^ "Ibuprofen". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Concomitant Use of Ibuprofen and Aspirin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). September 2006. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Lay summary in: "Information about Taking Ibuprofen and Aspirin Together". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 9 September 2019.

- PMID 28063133.

- PMID 2188537.

- S2CID 25223555.

- ^ PMID 12737366.

- S2CID 38588541.

- S2CID 218865551.

- PMID 3777588.

- S2CID 28521248.

- PMID 24491470.

- PMID 19203472.

- PMID 18363350.

- ^ a b "Ibuprofen". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 21 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- PMID 22350947.

- PMID 33197553.

- PMID 32832995.

- PMID 22043330.

- ^ a b Brayfield A, ed. (14 January 2014). "Ibuprofen". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "The Synthesis of Ibuprofen". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "The Ibuprofen Revolution". Science. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- S2CID 254510261.

- ISSN 2168-0485.

- ^ US4981995A, Elango V, Murphy MA, Smith BL, Davenport KG, "Method for producing ibuprofen", issued 1991-01-01

- hdl:1808/18897.

- PMID 1352228.

- PMID 1859831.

- S2CID 835701. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2 March 2019.

- PMID 3276314.

- S2CID 38829275.

- S2CID 40669413.

- S2CID 22857259.

- ^ "Molecule of the Week Archive: Ibuprofen". American Chemical Society. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ PMID 12723739.

- ^ Lambert V (8 October 2007). "Dr Stewart Adams: 'I tested ibuprofen on my hangover'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.(Subscription required.)

- ^ "A brief History of Ibuprofen". Pharmaceutical Journal. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Boots Hidden Heroes - Honoring Dr Stewart Adams" (Press release). Boots. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Chemical landmark plaque honours scientific discovery past and future" (Press release). Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC). 21 November 2013.

- ^ "Written submission to the NDAC meeting on risks of NSAIDs presented by the International Ibuprofen Foundation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). August 2002. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "New Drug Application (NDA): 017463". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "New Drug Application (NDA): 018989". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "Ibuprofen". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 16 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Drug Approval Package: Caldolor (Ibuprofen) NDA #022348". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012.

- ^ "FDA Approves Injectable Form of Ibuprofen" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- PMID 6239884.

- S2CID 195105870.

- PMID 7041104.

- S2CID 35357112.

- PMID 25227314.

- S2CID 30843070.

- S2CID 46104705.

- PMID 21368281.

- S2CID 35880887.

- PMID 21334642.

- S2CID 1828900.

External links

- GB patent 971700, Stewart Sanders Adams & John Stuart Nicholson, "Anti-Inflammatory Agents", published 1964-09-30, assigned to Boots Pure Drug Co Ltd

- "Evidence for the efficacy of pain medications" (PDF). National Safety Council (NSC). 26 August 2020.

- Lowe D. "The Ibuprofen Revolution". Science.