Iconoclasm

- Alemannisch

- العربية

- Asturianu

- Basa Bali

- বাংলা

- Български

- Català

- Čeština

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Eesti

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Frysk

- Gaeilge

- Galego

- 한국어

- Հայերեն

- हिन्दी

- Hrvatski

- Ido

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Italiano

- עברית

- Latina

- Lëtzebuergesch

- Lietuvių

- Magyar

- Македонски

- Bahasa Melayu

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk bokmål

- Norsk nynorsk

- پښتو

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Русский

- Shqip

- Sicilianu

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Tagalog

- தமிழ்

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- اردو

- Tiếng Việt

- 吴语

- 粵語

- 中文

Iconoclasm (from Greek: εἰκών, eikṓn, 'figure, icon' + κλάω, kláō, 'to break')[i] is the social belief in the importance of the destruction of icons and other images or monuments, most frequently for religious or political reasons. People who engage in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, a term that has come to be figuratively applied to any individual who challenges "cherished beliefs or venerated institutions on the grounds that they are erroneous or pernicious."[1]

Conversely, one who reveres or venerates religious images is called (by iconoclasts) an

While iconoclasm may be carried out by adherents of a different religion, it is more commonly the result of sectarian disputes between factions of the same religion. The term originates from the Byzantine Iconoclasm, the struggles between proponents and opponents of religious icons in the Byzantine Empire from 726 to 842 AD. Degrees of iconoclasm vary greatly among religions and their branches, but are strongest in religions which oppose idolatry, including the Abrahamic religions.[3] Outside of the religious context, iconoclasm can refer to movements for widespread destruction in symbols of an ideology or cause, such as the destruction of monarchist symbols during the French Revolution.

Early religious iconoclasm

Ancient era

In the

In rebellion against

the old religion and the powerful priests of Amun, Akhenaten ordered the eradication of all of Egypt's traditional gods. He sent royal officials to chisel out and destroy every reference to Amun and the names of other deities on tombs, temple walls, and cartouches to instill in the people that the Atenwas the one true god.

Public references to Akhenaten were destroyed soon after his death. Comparing the ancient Egyptians with the Israelites, Jan Assmann writes:[6]

For Egypt, the greatest horror was the destruction or abduction of the cult images. In the eyes of the Israelites, the erection of images meant the destruction of

and Akhenaten became, after all, closely related.

Judaism

According to the

In Judaism, King Hezekiah purged Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem and all figures were also destroyed in the Land of Israel, including the Nehushtan, as recorded in the Second Book of Kings. His reforms were reversed in the reign of his son Manasseh.[8]

Iconoclasm in Christian history

Scattered expressions of

Among early church theologians, iconoclastic tendencies were supported by theologians such as Tertullian,[13][14][15] Clement of Alexandria,[14] Origen,[16][15] Lactantius,[17] Justin Martyr,[15] Eusebius and Epiphanius.[14][18]

Byzantine era

One notable change within the

Government-led iconoclasm began with Byzantine Emperor Leo III, who issued a series of edicts between 726 and 730 against the veneration of images.[22] The religious conflict created political and economic divisions in Byzantine society; iconoclasm was generally supported by the Eastern, poorer, non-Greek peoples of the Empire who had to frequently deal with raids from the new Muslim Empire.[23] On the other hand, the wealthier Greeks of Constantinople and the peoples of the Balkan and Italian provinces strongly opposed iconoclasm.[23]

Pre-Reformation

Peter of Bruys opposed the usage of religious images,[24] the Strigolniki were also possibly iconoclastic.[25] Claudius of Turin was the bishop of Turin from 817 until his death.[26] He is most noted for teaching iconoclasm.[26]

Reformation era

The first iconoclastic wave happened in Wittenberg in the early 1520s under reformers Thomas Müntzer and Andreas Karlstadt, in the absence of Martin Luther, who then, concealed under the pen-name of 'Junker Jörg', intervened to calm things down. Luther argued that the mental picturing of Christ when reading the Scriptures was similar in character to artistic renderings of Christ.[27]

In contrast to the

The belief of iconoclasm caused havoc throughout Europe. In 1523, specifically due to the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli, a vast number of his followers viewed themselves as being involved in a spiritual community that in matters of faith should obey neither the visible Church nor lay authorities. According to Peter George Wallace "Zwingli's attack on images, at the first debate, triggered iconoclastic incidents in Zürich and the villages under civic jurisdiction that the reformer was unwilling to condone." Due to this action of protest against authority, "Zwingli responded with a carefully reasoned treatise that men could not live in society without laws and constraint".[30]

Significant iconoclastic riots took place in Basel (in 1529), Zürich (1523), Copenhagen (1530), Münster (1534), Geneva (1535), Augsburg (1537), Scotland (1559), Rouen (1560), and Saintes and La Rochelle (1562).[31][32] Calvinist iconoclasm in Europe "provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs" in Germany and "antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox" in the Baltic region.[33]

The Seventeen Provinces (now the Netherlands, Belgium, and parts of Northern France) were disrupted by widespread Calvinist iconoclasm in the summer of 1566.[34]

- Calvinist iconoclasm during the Reformation

-

Destruction of religious images by the Reformed in Zürich, Switzerland, 1524

-

Calvinists in 1562 by Antoine Caron

-

Remains of Calvinist iconoclasm, Clocher Saint-Barthélémy, La Rochelle, France

During the

During the

Lord what work was here! What clattering of glasses! What beating down of walls! What tearing up of monuments! What pulling down of seats! What wresting out of irons and brass from the windows! What defacing of arms! What demolishing of curious stonework! What tooting and piping upon organ pipes! And what a hideous triumph in the market-place before all the country, when all the mangled organ pipes, vestments, both copes and surplices, together with the leaden cross which had newly been sawn down from the Green-yard pulpit and the service-books and singing books that could be carried to the fire in the public market-place were heaped together.

Protestant Christianity was not uniformly hostile to the use of religious images. Martin Luther taught the "importance of images as tools for instruction and aids to devotion,"[42] stating: "If it is not a sin but good to have the image of Christ in my heart, why should it be a sin to have it in my eyes?"[43] Lutheran churches retained ornate church interiors with a prominent crucifix, reflecting their high view of the real presence of Christ in Eucharist.[44][28] As such, "Lutheran worship became a complex ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior."[44] For Lutherans, "the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image."[45]

Lutheran scholar Jeremiah Ohl writes:

A bit later in Dutch history, in 1627 the artist Johannes van der Beeck was arrested and tortured, charged with being a religious non-conformist and a blasphemer, heretic, atheist, and Satanist. The 25 January 1628 judgment from five noted advocates of The Hague pronounced him guilty of "blasphemy against God and avowed atheism, at the same time as leading a frightful and pernicious lifestyle. At the court's order his paintings were burned, and only a few of them survive."[49]

Other instances

In Japan during the early modern age, the spread of Catholicism also involved the repulsion of non-Christian religious structures, including Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines and figures. At times of conflict with rivals or some time after the conversion of several daimyos, Christian converts would often destroy Buddhist and Shinto religious structures.[50]

Many of the moai of Easter Island were toppled during the 18th century in the iconoclasm of civil wars before any European encounter.[51] Other instances of iconoclasm may have occurred throughout Eastern Polynesia during its conversion to Christianity in the 19th century.[52]

After the Second Vatican Council in the late 20th century, some Roman Catholic parish churches discarded much of their traditional imagery, art, and architecture.[53]

Muslim iconoclasm

Islam has a strong tradition of forbidding the depiction of figures, especially religious figures,[3] with Sunni Islam forbidding it more than Shia Islam. In the

In general, Muslim societies have

Early Islam in Arabia

The first act of Muslim iconoclasm dates to the beginning of Islam, in 630, when the various statues of

The destruction of the idols of Mecca did not, however, determine the treatment of other religious communities living under Muslim rule after the expansion of the

Egypt

Ottoman conquests

Certain conquering Muslim armies have used local temples or houses of worship as mosques. An example is Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), which was converted into a mosque in 1453. Most icons were desecrated and the rest were covered with plaster. In 1934 the government of Turkey decided to convert the Hagia Sophia into a museum and the restoration of the mosaics was undertaken by the American Byzantine Institute beginning in 1932.

Contemporary events

Certain Muslim denominations continue to pursue iconoclastic agendas. There has been much controversy within Islam over the recent and apparently on-going destruction of historic sites by Saudi Arabian authorities, prompted by the fear they could become the subject of "idolatry."[60][61]

A recent act of iconoclasm was the 2001 destruction of the giant

During the Tuareg rebellion of 2012, the radical Islamist militia Ansar Dine destroyed various Sufi shrines from the 15th and 16th centuries in the city of Timbuktu, Mali.[63] In 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) sentenced Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi, a former member of Ansar Dine, to nine years in prison for this destruction of cultural world heritage. This was the first time that the ICC convicted a person for such a crime.[64]

The

Iconoclasm in India

In early Medieval India, there were numerous recorded instances of temple desecration mostly by Indian Muslim kings against rival Indian Hindu kingdoms, which involved conflicts between Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains.[67][68][69]

In the 8th century, Bengali troops from the Buddhist

During the Muslim conquest of Sindh

Records from the campaign recorded in the

Historian Upendra Thakur records the persecution of

Muhammad triumphantly marched into the country, conquering

Nerun, Brahmanadabad, Alor and Multan one after the other in quick succession, and in less than a year and a half, the far-flung Hindu kingdom was crushed ... There was a fearful outbreak of religious bigotry in several places and temples were wantonly desecrated. At Debal, the Nairun and Aror temples were demolished and converted into mosques.[71]

- Iconoclasm during the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

-

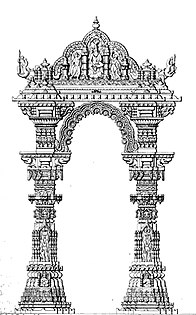

TheSomnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[72] The present temple was reconstructed in Chalukyan style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[73][74]

-

TheQutb al-Din Aibak.

-

Ruins of theSikandar Butshikanin the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

-

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.

-

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[68]

-

Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[68]

-

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.

-

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[75]

The Somnath temple and Mahmud of Ghazni

Perhaps the most notorious episode of iconoclasm in India was

The wooden structure was replaced by Kumarapala (r. 1143–72), who rebuilt the temple out of stone.[82]

From the Mamluk dynasty onward

Historical records which were compiled by the Muslim historian Maulana Hakim Saiyid Abdul Hai attest to the religious violence which occurred during the

During the Delhi Sultanate, a Muslim army led by Malik Kafur, a general of Alauddin Khalji, pursued four violent campaigns into south India, between 1309 and 1311, against the Hindu kingdoms of Devgiri (Maharashtra), Warangal (Telangana), Dwarasamudra (Karnataka) and Madurai (Tamil Nadu). Many Temples were plundered; Hoysaleswara Temple and others were ruthlessly destroyed.[86][87]

In Kashmir, Sikandar Shah Miri (1389–1413) began expanding, and unleashed religious violence that earned him the name but-shikan, or 'idol-breaker'.[88] He earned this sobriquet because of the sheer scale of desecration and destruction of Hindu and Buddhist temples, shrines, ashrams, hermitages, and other holy places in what is now known as Kashmir and its neighboring territories. Firishta states, "After the emigration of the Brahmins, Sikundur ordered all the temples in Kashmeer to be thrown down."[89] He destroyed vast majority of Hindu and Buddhist temples in his reach in Kashmir region (north and northwest India).[90]

In the 1460s,

A regional tradition, along with the Hindu text Madala Panji, states that Kalapahar attacked and damaged the Konark Sun Temple in 1568, as well as many others in Orissa.[91][92]

Some of the most dramatic cases of iconoclasm by Muslims are found in parts of India where Hindu and Buddhist temples were razed and mosques erected in their place.

During the Goa Inquisition

Exact data on the nature and number of Hindu temples destroyed by the Christian missionaries and Portuguese government are unavailable. Some 160 temples were allegedly razed to the ground in Tiswadi (Ilhas de Goa) by 1566. Between 1566 and 1567, a campaign by Franciscan missionaries destroyed another 300 Hindu temples in Bardez (North Goa). In Salcete (South Goa), approximately another 300 Hindu temples were destroyed by the Christian officials of the Inquisition. Numerous Hindu temples were destroyed elsewhere at Assolna and Cuncolim by Portuguese authorities.[94] A 1569 royal letter in Portuguese archives records that all Hindu temples in its colonies in India had been burnt and razed to the ground.[95] The English traveller Sir Thomas Herbert, 1st Baronet who visited Goa in the 1600s writes:

... as also the ruins of 200 Idol Temples which the Vice-Roy Antonio Norogna totally demolisht, that no memory might remain, or monuments continue, of such gross Idolatry. For not only there, but at Salsette also were two Temples or places of prophane Worship; one of them (by incredible toil cut out of the hard Rock) was divided into three Iles or Galleries, in which were figured many of their deformed Pagotha's, and of which an Indian (if to be credited) reports that there were in that Temple 300 of those narrow Galleries, and the Idols so exceeding ugly as would affright an European Spectator; nevertheless this was a celebrated place, and so abundantly frequented by Idolaters, as induced the Portuguise in zeal with a considerable force to master the Town and to demolish the Temples, breaking in pieces all that monstrous brood of mishapen Pagods. In Goa nothing is more observable now than the fortifications, the Vice-Roy and Arch-bishops Palaces, and the Churches. ...[96]

In modern India

Dr. Ambedkar and his supporters on 25 December 1927 in the Mahad Satyagraha strongly criticised, condemned and then burned copies of Manusmriti on a pyre in a specially dug pit. Manusmriti, one of the sacred Hindu texts, is the religious basis of casteist laws and values of Hinduism and hence was/is the reason of social and economic plight of crores of untouchables and lower caste Hindus. One of the greatest iconoclasts for all time, this explosive incident rocked the Hindu society. Ambedkarites continue to observe 25 December as "Manusmriti Dahan Divas" (Manusmriti Burning Day) and burn copies of Manusmriti on this day.

The most high-profile case of Independent India was in 1992. Hindu mob, led by the Vishva Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal, destroyed the 430-year-old Islamic Babri Masjid in Ayodhya which is claimed to be built after destroying the Ram Mandir.[97][98]

Iconoclasm in East Asia

China

There have been

During and after the 1911

During the

There was extensive destruction of religious and secular imagery in

Many religious and secular images were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976, ostensibly because they were a holdover from China's traditional past (which the Communist regime led by Mao Zedong reviled). The Cultural Revolution included widespread destruction of historic artworks in public places and private collections, whether religious or secular. Objects in state museums were mostly left intact.

South Korea

According to an article in

Angkor

Beginning c. 1243 AD with the death of Indravarman II, the Khmer Empire went through a period of iconoclasm. At the beginning of the reign of the next king, Jayavarman VIII, the Kingdom went back to Hinduism and the worship of Shiva. Many of the Buddhist images were destroyed by Jayavarman VIII, who reestablished previously Hindu shrines that had been converted to Buddhism by his predecessor. Carvings of the Buddha at temples such as Preah Khan were destroyed, and during this period the Bayon Temple was made a temple to Shiva, with the central 3.6 meter tall statue of the Buddha cast to the bottom of a nearby well.[104]

Political iconoclasm

Damnatio memoriae

Revolutions and changes of regime, whether through uprising of the local population, foreign invasion, or a combination of both, are often accompanied by the public destruction of statues and monuments identified with the previous regime. This may also be known as damnatio memoriae, the ancient Roman practice of official obliteration of the memory of a specific individual. Stricter definitions of "iconoclasm" exclude both types of action, reserving the term for religious or more widely cultural destruction.[

Among Roman emperors and other political figures subject to decrees of damnatio memoriae were

had during their reigns erected numerous statues of themselves, which were pulled down and destroyed when they were overthrown.The perception of damnatio memoriae in the Classical world was an act of erasing memory has been challenged by scholars who have argued that it "did not negate historical traces, but created gestures which served to dishonor the record of the person and so, in an oblique way, to confirm memory,"[105] and was in effect a spectacular display of "pantomime forgetfulness."[106] Examining cases of political monument destruction in modern Irish history, Guy Beiner has demonstrated that iconoclastic vandalism often entails subtle expressions of ambiguous remembrance and that, rather than effacing memory, such acts of de-commemorating effectively preserve memory in obscure forms.[107][108][109]

During the French Revolution

Throughout the radical phase of the

Some episodes of iconoclasm were carried out spontaneously by crowds of citizens, including the destruction of statues of kings during the insurrection of 10 August 1792 in Paris.[112] Some were directly sanctioned by the Republican government, including the Saint-Denis exhumations.[111] Nonetheless, the Republican government also took steps to preserve historic artworks,[113] notably by founding the Louvre museum to house and display the former royal art collection. This allowed the physical objects and national heritage to be preserved while stripping them of their association with the monarchy.[114][115][116] Alexandre Lenoir saved many royal monuments by diverting them to preservation in a museum.[117]

The statue of

After Napoleon conquered the Italian city of Pavia, local Pavia Jacobins destroyed the Regisole, a bronze classical equestrian monument dating back to Classical times. The Jacobins considered it a symbol of Royal authority, but it had been a prominent Pavia landmark for nearly a thousand years and its destruction aroused much indignation and precipitated a revolt by inhabitants of Pavia against the French, which was quelled by Napoleon after a furious urban fight.

Other examples

Other examples of political destruction of images include:

- There have been several cases of removing symbols of past rulers in Malta's history. Many Hospitaller coats of arms on buildings were defaced during the French occupation of Malta in 1798–1800; a few of these were subsequently replaced by British coats of arms in the early 19th century.[118] Some British symbols were also removed by the government after Malta became a republic in 1974. These include royal cyphers being ground off from post boxes,[119] and British coats of arms such as that on the Main Guard building being temporarily obscured (but not destroyed).[120]

- With the entry of the Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı—the oldest known Turkish-made film.

- In the late 18th century, occupied Belgium during the First World War, disliked the monument and destroyed it in 1915. It was restored in 1926 by the International Free Thought Movement.[123]

- In 1942, the pro-Nazi Vichy Government of France took down and melted Clothilde Roch's statue of the 16th-century dissident intellectual Michael Servetus, who had been burned at the stake in Geneva at the instigation of Calvin. The Vichy authorities disliked the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience. In 1960, having found the original molds, the municipality of Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.[124]

- A sculpture of the head of Spanish intellectual Nationalist side. During the Spanish Civil War, it was thrown into the estuary. It was later recovered. In 1984 the head was installed in Plaza Unamuno. In 1999, it was again thrown into the estuary after a political meeting of Euskal Herritarrok. It was substituted by a copy in 2000 after the original was located in the water.[125][126][127]

- The Battle of Baghdad and the regime of Saddam Hussein symbolically ended with the Firdos Square statue destruction, a U.S. military-staged event on 9 April 2003 where a prominent statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down. Subsequently, statues and murals of Saddam Hussein all over Iraq were destroyed by US occupation forces as well as Iraqi citizens.[128]

- In 2016, paintings from the University of Cape Town, South Africa, were burned in student protests as symbols of colonialism.[129]

- In November 2019, a statue of Swedish footballer Zlatan Ibrahimović in Malmö, Sweden, was vandalized by Malmö FF supporters after he announced he had become part-owner of Swedish rivals Hammarby. White paint was sprayed on it; threats and hateful messages towards Zlatan were written on the statue, and it was burned.[130][131] In a second attack the nose was sawed off and the statue was sprinkled with chrome paint.[132] On 5 January 2020 it was finally toppled.[133]

- On 7 June 2020, during the George Floyd protests,[134] a statue of merchant and trans-Atlantic slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, UK, was pulled down by demonstrators who then jumped on it.[135] They daubed it in red and blue paint, and one protester placed his knee on the statue's neck to allude to Floyd's murder by a white policeman who knelt on Floyd's neck for over nine minutes.[134][136] The statue was then rolled down Anchor Road and pushed into Bristol Harbour.[135][137][138]

In the Soviet Union

During and after the

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and during the Revolutions of 1989, protesters often attacked and took down sculptures and images of Joseph Stalin, such as the Stalin Monument in Budapest.[140]

The fall of Communism in 1989–1991 was also followed by the destruction or removal of statues of

In the United States

In August 2017, a statue of a

2020 demonstrations

During the George Floyd protests of 2020, demonstrators pulled down dozens of statues which they considered symbols of the Confederacy, slavery, segregation, or racism, including the statue of Williams Carter Wickham in Richmond, Virginia.[145][146]

Further demonstrations in the wake of the George Floyd protests have resulted in the removal of:[147]

- the John Breckenridge Castleman monument in Louisville, Kentucky;

- plaques in Hemming Park (renamed in 1899 in honor of Civil War veteran Charles C. Hemming), which were in remembrance of deceased Confederatesoldiers;

- the monumental obelisk of the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument and a statue of Charles Linn in Linn Park, Birmingham, Alabama;

- a statue of Junípero Serra in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco;[148]

- a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Montgomery, Alabama;

- the monument to Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia;[149]

- the Appomattox statue in Alexandria, Virginia, leaving the monument's base empty but intact.

Multiple statues of early European explorers and founders were also vandalized, including those of Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson.[150][151]

- Christopher Columbus was removed in Virginia, Minnesota, Chicago and beheaded in Boston MA.[150]

- George Washington statue was toppled in Portland, Oregon.[151]

A statue of the African-American abolitionist statesman Frederick Douglass was vandalised in Rochester, New York, by being torn from its base and left close to a nearby river gorge. Donald Trump attributed the act to anarchists,[152] but he did not substantiate his claim nor did he offer a theory on motive. Cornell William Brooks, former president of the NAACP, theorised that this was an act of revenge from white supremacists.[153] Carvin Eison, who led the project that brought the Douglass statues to Rochester, thought it was unlikely that the Douglass statue was toppled by someone who was upset about monuments honoring Confederate figures, and added that "it's only logical that it was some kind of retaliation event in someone's mind". Police did not find evidence that supported or refuted either claim, and the vandalism case remains unsolved.[154]

See also

- Aniconism

- Censorship by religion

- Cult image

- Cultural Revolution

- Icon

- Iconolatry

- List of destroyed heritage

- Lost artworks

- Natural theology

- Slighting

- Council of Constantinople (843)

Notes

- Ancient Greek: εἰκών + κλάω, lit. 'image-breaking'. Iconoclasm may also be considered as a back-formationfrom iconoclast (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, eikonoklasia.

References

- ^ "Iconoclast, 2," Oxford English Dictionary; see also "Iconoclasm" and "Iconoclastic."

- ^ "icono-, comb. form". OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Crone, Patricia. 2005. "Islam, Judeo-Christianity and Byzantine Iconoclasm Archived 2018-11-11 at the Wayback Machine." pp. 59–96 in From Kavād to al-Ghazālī: Religion, Law and Political Thought in the Near East, c. 600–1100, (Variorum). Ashgate Publishing.

- ^ H. James Birx, Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Volume 1, Sage Publications, US, 2006, p. 802

- ^ "Akhenaten." Encyclopedia of World Biography. 20 June 2020. via Encyclopedia.com.

- ISBN 977-416-631-0. p. 76.

- ^ Bible, Numbers 33:52 and similarly Bible, Deuteronomy 7:5

- ^ "2 Kings 21 / Hebrew–English Bible / Mechon-Mamre". mechon-mamre.org. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Elvira canons, Cua, archived from the original on 2012-07-16,

Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur

. - ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia,

This canon has often been urged against the veneration of images as practised in the Catholic Church. Binterim, De Rossi, and Hefele interpret this prohibition as directed against the use of images in overground churches only, lest the pagans should caricature sacred scenes and ideas; Von Funk, Termel, and Henri Leclercq opine that the council did not pronounce as to the liceity or non-liceity of the use of images, but as an administrative measure simply forbade them, lest new and weak converts from paganism should incur thereby any danger of relapse into idolatry, or be scandalized by certain superstitious excesses in no way approved by the ecclesiastical authority.

- S2CID 162369274.

- ^ "The Council of Elvira, ca. 306". Archived from the original on 2016-02-29. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ISBN 978-0-19-154196-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-95170-2.

- ^ a b c Strezova, Anita (2013-11-25). "Overview on Iconophile and Iconoclastic Attitudes toward Images in Early Christianity and Late Antiquity". Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies.

- ISBN 978-0-226-31023-7.

- ISBN 978-90-04-46200-7.

- ^ Kitzinger, 92–93, 92 quoted

- ^ "Byzantine iconoclasm". Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ISBN 0-540-01085-5.

- ISBN 0-7044-0226-2.

- ^ Treadgold, Warren. 1997. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. pp. 350, 352–353.

- ^ a b Mango, Cyril. 2002. The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press.

- ISBN 978-1-61097-970-2.

- ISBN 978-1-134-92102-7.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-211655-X.

- ^ Dorner, Isaak August. 1871. History of Protestant Theology. Edinburgh. p. 146.

- ^ ISBN 978-1442271593.has noted that Lutherans, seeing themselves in the tradition of the ancient, apostolic church, sought to defend as well as reform the use of images. "An empty, white-washed church proclaimed a wholly spiritualized cult, at odds with Luther's doctrine of Christ's real presence in the sacraments" (Koerner 2004, 58). In fact, in the 16th century some of the strongest opposition to destruction of images came not from Catholics but from Lutherans against Calvinists: "You black Calvinist, you give permission to smash our pictures and hack our crosses; we are going to smash you and your Calvinist priests in return" (Koerner 2004, 58). Works of art continued to be displayed in Lutheran churches, often including an imposing large crucifix in the sanctuary, a clear reference to Luther's theologia crucis. ... In contrast, Reformed (Calvinist) churches are strikingly different. Usually unadorned and somewhat lacking in aesthetic appeal, pictures, sculptures, and ornate altar-pieces are largely absent; there are few or no candles; and crucifixes or crosses are also mostly absent.

Lutherans continued to worship in pre-Reformation churches, generally with few alterations to the interior. It has even been suggested that in Germany to this day one finds more ancient Marian altarpieces in Lutheran than in Catholic churches. Thus in Germany and in Scandinavia many pieces of medieval art and architecture survived. Joseph Koerner

- ^ ISBN 978-9004291621.

Luther's view was that biblical images could be used as teaching aids, and thus had didactic value. Hence Luther stood against the destruction of images whereas several other reformers (Karlstadt, Zwingli, Calvin) promoted these actions. In the following passage, Luther harshly rebukes Karlstadt on his stance on iconoclasm and his disorderly conduct in reform.

- ^ Wallace, Peter George. 2004. The Long European Reformation: Religion, Political Conflict, and the Search for Conformity, 1350–1750. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 95.

- ISBN 978-0801873904. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ISBN 978-0-521-47222-7.

- ISBN 978-0191578885.

Iconoclastic incidents during the Calvinist 'Second Reformation' in Germany provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs, while Protestant image-breaking in the Baltic region deeply antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox, a group with whom reformers might have hoped to make common cause.

- ISBN 978-1424069224.

In an episode known as the Great Iconoclasm, bands of Calvinists visited Catholic churches in the Netherlands in 1566, shattering stained-glass windows, smashing statues, and destroying paintings and other artworks they perceived as idolatrous.

- ISBN 978-1588365002.

The Beeldenstorm, or Iconoclastic Fury, involved roving bands of radical Calvinists who were utterly opposed to all religious images and decorations in churches and who acted on their beliefs by storming into Catholic churches and destroying all artwork and finery.

- ISBN 978-0968987391.

Devoutly Catholic but opposed to Inquisition tactics, they backed William of Orange in subduing the Calvinist uprising of the Dutch beeldenstorm on behalf of regent Margaret of Parma, and had come willingly to the council at her invitation.

- ISBN 978-0-521-48457-2.

- ISBN 978-0-300-07992-0

- ISBN 978-0-8478-1940-9

- ISBN 978-0-19-928015-5(pp. 263–264)

- ^ Evelyn White, Parliamentary Visitor (1886). "The Journal of William Dowsing, Parliamentary Visitor" (PDF). Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. VI (Part 2): 236 to 295.

- ISBN 978-0820486857.

Although some reformers, such as John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli, rejected all images, Martin Luther defended the importance of images as tools for instruction and aids to devotion.

- ISBN 978-0761843375.

- ^ ISBN 978-1351921169.

As it developed in north-eastern Germany, Lutheran worship became a complex ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior. This much is evident from the background of an epitaph pained in 1615 by Martin Schulz, destined for the Nikolaikirche in Berlin (see Figure 5.5.).

- ISBN 978-1118272305.

According to Koerner, who dwells on Lutheran art, the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image.

- ^ Ohl, Jeremiah F. 1906. "Art in Worship." pp. 83–99 in Memoirs of the Lutheran Liturgical Association 2. Pittsburgh: Lutheran Liturgical Association.

- ISBN 978-90-04-03945-2.

- ISBN 978-1932688078– via Google Books.

- ISBN 1-56459-972-8.

- S2CID 229468278.

- OCLC 646808462.

- ^ Wellington, Victoria University of (April 4, 2014). "New view of Polynesian conversion to Christianity". Victoria University of Wellington.

- ^ Chessman, Stuart. "Hetzendorf and the Iconoclasm in the Second Half of the 20th Century". The Society of St. Hugh of Cluny. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ JSTOR 3177288.

- ISBN 978-0-19-636033-1. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

Quraysh had put pictures in the Ka'ba including two of Jesus son of Mary and Mary (on both of whom be peace!). ... The apostle ordered that the pictures should be erased except those of Jesus and Mary.

- ISBN 978-2-08-012603-0.

- S2CID 162882785.

- ^ "What happened to the Sphinx's nose?". Smithsonian Journeys. Smithsonian Institution. December 8, 2009.

- ISBN 978-0801489549– via Internet Archive.

- ^ Howden, Daniel (August 6, 2005). "Independent Newspaper on-line, London, Jan 19, 2007". News.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Ahmed, Irfan (2006). "The Destruction of Holy Sites in Mecca and Medina". Islamica Magazine. No. 15. Archived from the original on 5 February 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Afghan Taliban leader orders destruction of ancient statues". Rawa.org. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (2012-07-02). "Timbuktu's Destruction: Why Islamists Are Wrecking Mali's Cultural Heritage". Time. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Nine Years for the Cultural Destruction of Timbuktu". The Atlantic. 2016-09-27. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "Iraq jihadists blow up 'Jonah's tomb' in Mosul". The Telegraph. Agence France-Presse. 25 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "ISIS destroys Prophet Sheth shrine in Mosul". Al Arabiya News. 26 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Eaton, Richard M. (9 December 2000). "Temple desecration in pre-modern India". Frontline. Vol. 17, no. 25. The Hindu Group. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- ^ ISSN 0955-2340.

- ^ ISBN 978-8178710273.

- ^ Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg: The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. [1] Archived 2017-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sindhi Culture by U. T. Thakkur, Univ. of Bombay Publications, 1959.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (5 January 2001). "Temple desecration and Indo-Muslim states" (PDF). Frontline. Vol. 17, no. 26. The Hindu Group. p. 73 – via Columbia University, item 16 of the Table. Issue 26 online.

- ISBN 81-85880-26-3.

- ISBN 1-85065-170-1.

- ISBN 978-0-658-01151-1.

- ^ "Gujarat State Portal | All About Gujarat | Gujarat Tourism | Religious Places | Somnath Temple". Gujaratindia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ISBN 978-1844670208– via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 8184751850.

- ^ "Leaves from the past". Archived from the original on 2007-01-10.

- ^ ISBN 1-84467-020-1.

- ISBN 978-9351940944.

- ^ Somnath Temple Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, British Library.

- ^ "Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- JSTOR 1523075: TheQuwwatu'l-Islamwas built with the remains of demolished Hindu and Jain temples.

- ^ Pritchett, Frances W. "Indian routes: Some memorable ventures, adventures, and other happenings, in and about south Asia: 1200–1299" – via Columbia University.

- ISBN 0-415-15482-0, pp. 160–161

- ISBN 978-0-14-333544-3.

- ISBN 90-04-097902. p. 793

- ^ Firishta, Muhammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh (1981) [1829]. Tārīkh-i-Firishta [History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India]. Translated by John Briggs. New Delhi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Trubner & Co.p. 457.

- OCLC 52861120.

- OCLC 53385077.

- S2CID 165273975.

- ISBN 978-1-351-91276-1.

- ^ Teotonio R. De Souza (2016). The Portuguese in Goa, in Acompanhando a Lusofonia em Goa: Preocupações e experiências pessoais (PDF). Lisbon: Grupo Lusofona. pp. 28–30.

- ^ Herbert, Sir Thomas (1677). Some years travels into divers parts of Africa, and Asia the Great. London : R. Everingham for R. Scot, etc. p. 40.

- ^ Narula, Smita (October 1999). India politics by other means: Attacks Against Christians in India (Report). Vol. 11. Human Rights Watch. § The Context of Anti-Christian Violence.

- ^ Tully, Mark (5 December 2002). "Tearing down the Babri Masjid". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-2231-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ISBN 978-9401793759.

- .

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p. 133.

- ^ Hedrick, Charles W. (2000). History and Silence: Purge and Rehabilitation of Memory in Late Antiquity. University of Texas Press. pp. 88–130.

- ^ Stewart, Peter (2003). Statues in Roman Society: Representation and Response. Oxford University Press. pp. 279–283.

- ^ Beiner, Guy (2007). Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 305.

- ^ Beiner, Guy (2018). Forgetful Remembrance: Social Forgetting and Vernacular Historiography of a Rebellion in Ulster. Oxford University Press. pp. 369–384.

- S2CID 240526743.

- JSTOR 1842743.

- ^ a b Lindsay, Suzanne Glover (18 October 2014). "The Revolutionary Exhumations at St-Denis, 1793". Center for the Study of Material & Visual Cultures of Religion. Yale University.

- S2CID 159942339.

- OCLC 70883061.

- ISBN 978-0-415-12826-1.

- ^ Stanley J. Idzerda, "Iconoclasm during the French Revolution." In The American Historical Review, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Oct., 1954), p. 25.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987): 212–213.

- ^ Greene, Christopher M., "Alexandre Lenoir and the Musée des monuments français during the French Revolution," French Historical Studies 12, no. 2 (1981): pp. 200–222.

- ^ Ellul, Michael (1982). "Art and Architecture in Malta in the Early Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Melitensia Historica. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2016.

- ^ Westcott, Kathryn (18 January 2013). "Letter boxes: The red heart of the British streetscape". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016.

- ^ Bonello, Giovanni (14 January 2018). "Mysteries of the Main Guard inscription". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018.

- ^ Mardaga 1993, p. 121.

- ^ Hennaut 2000, p. 34–36.

- OCLC 489692159, p. 33.

- ISBN 978-0-7679-0837-5.

- ^ Uriona, Alberto (6 March 2000). "El Ayuntamiento de Bilbao restituye a su columna el busto de Unamuno nueve meses después de su robo". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Camacho, Isabel (9 June 1999). "La cabeza perdida de don Miguel". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Victorio Macho y Unamuno: notas para un centenario" (PDF) (in Spanish). Real Fundación Toledo. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Göttke, Florian. Toppled. Rotterdam: Post Editions, 2010.

- ^ Meintjies, Ilze-Marie (16 February 2016). "Protesting UCT Students Burn Historic Paintings, Refuse To Leave". Eyewitness News.

- ^ "Zlatan Ibrahimovic statue: Vandals try to saw through feet". BBC Sport. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019 – via BBC News.

- ^ Daniels, Tim. "Zlatan Ibrahimovic's Malmo Statue Set on Fire After Becoming Hammarby Part Owner". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Erberth, Nellie (December 22, 2019). "Zlatans staty vandaliserad igen – näsan avsågad". SVT Nyheter – via www.svt.se.

- ^ Wikén, Johan; Erberth, Nellie (January 5, 2020). "Zlatanstatyn vandaliserad igen – avsågad vid fötterna". SVT Nyheter – via www.svt.se.

- ^ a b "Protesters in England topple statue of slave trader Edward Colston into harbor". CBS News. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Siddique, Haroon (7 June 2020). "BLM protesters topple statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Zaks, Dmitry (8 June 2020). "UK slave trader's statue toppled in anti-racism protests". The Jakarta Post. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "George Floyd death: Protesters tear down slave trader statue". BBC News. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Rory (7 June 2020). "Black Lives Matter protesters pull down statue of 17th century UK slave trader". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Christopher Wharton, "The Hammer and Sickle: The Role of Symbolism and Rituals in the Russian Revolution" Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Auyezov, Olzhas (January 5, 2011). "Ukraine says blowing up Stalin statue was terrorism". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ "SEE IT: Crowd pulls down Confederate statue in North Carolina". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ Holland, Jesse J. "Deadly rally accelerates ongoing removal of Confederate statues across U.S." chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ "War over Confederate statues reveals simple thinking on all sides". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ Jackson, Amanda (15 August 2017). "Protesters pull down Confederate statue in North Carolina". CNN. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ Fultz, Matthew (7 June 2020). "Crew heard cheers as Confederate general's statue toppled in Monroe Park". WTVR.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. "Photos: The Statues Brought Down Since the George Floyd Protests Began". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Ebrahimji, Alisha; Moshtaghian, Artemis. "These confederate statues have been removed since George Floyd's death". CNN. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- ^ "San Francisco Archbishop Outraged Over Toppling Of Golden Gate Park Junipero Serra Statue". 2020-06-21. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Schneider, Gregory S.; Vozzella, Laura (2021-09-08). "Robert E. Lee statue is removed in Richmond, ex-capital of Confederacy, after months of protests and legal resistance". Washington Post. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

- ^ a b Asmelash, Leah (10 June 2020). "Statues of Christopher Columbus are being dismounted across the country". CNN. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- ^ a b Williams, David (19 June 2020). "Protesters tore down a George Washington statue and set a fire on its head". CNN. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ^ Trump, Donald (6 July 2020). "Statue of Frederick Douglass Torn Down in Rochester, via Breitbart News. This shows that these anarchists have no bounds!". Donald Trump. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ Brooks, Cornell (6 July 2020). "#FrederickDouglass's statue was ripped from the ground. Some may call this REVENGE – remove our #WhiteSupremacists and we remove your #Abolitionist. I call this DESECRATION. Listen to his words and know why his truth is admired and feared". Cornell William Brooks. Retrieved 20 March 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Gold, Michael (7 July 2020). "Who Tore Down This Frederick Douglass Statue?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

Further reading

- Alloa, Emmanuel (2013). "Visual Studies in Byzantium: A Pictorial Turnavant la lettre". Journal of Visual Culture. 12 (1). Sage: 3–29. S2CID 191395643. (On the conceptual background of Byzantine iconoclasm)

- ISBN 978-0-19-822438-9.

- —— 2016. Broken Idols of the English Reformation. Cambridge University Press.

- Balafrej, Lamia (2 September 2015). "Islamic iconoclasm, visual communication and the persistence of the image". Interiors. 6 (3). Informa UK: 351–366. S2CID 131284640.

- Barasch, Moshe. 1992. Icon: Studies in the History of an Idea. ISBN 978-0-8147-1172-9.

- Beiner, Guy (2021). "When Monuments Fall: The Significance of Decommemorating". Éire-Ireland. 56 (1): 33–61. S2CID 240526743.

- Besançon, Alain. 2000. The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. ISBN 978-0-226-04414-9.

- Bevan, Robert. 2006. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. ISBN 978-1-86189-319-2.

- Boldrick, Stacy, Leslie Brubaker, and Richard Clay, eds. 2014. Striking Images, Iconoclasms Past and Present. Ashgate. (Scholarly studies of the destruction of images from prehistory to the Taliban.)

- Calisi, Antonio. 2017. I Difensori Dell'icona: La Partecipazione Dei Vescovi Dell'Italia Meridionale Al Concilio Di Nicea II 787. ISBN 978-1978401099.

- Freedberg, David. 1977. "The Structure of Byzantine and European Iconoclasm." Pp. 165–77 in Iconoclasm: Papers Given at the Ninth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, edited by A. Bryer and J. Herrin. ISBN 978-0-7044-0226-3.

- —— [1985] 1993. "Iconoclasts and their Motives," (Second Horst Gerson Memorial Lecture, University of Groningen). Public 8(Fall).

- Original print: Maarssen: Gary Schwartz. 1985. ISBN 978-90-6179-056-3.

- Original print: Maarssen: Gary Schwartz. 1985.

- Gamboni, Dario (1997). The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-316-1.

- Gwynn, David M (2007). "From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy" (PDF). Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 47: 225–251. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-16. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- Hennaut, Eric (2000). La Grand-Place de Bruxelles. Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Ivanovic, Filip (2010). Symbol and Icon: Dionysius the Areopagite and the Iconoclastic Crisis. Pickwick. ISBN 978-1-60899-335-2.

- Karahan, Anne (2014). "Byzantine Iconoclasm: Ideology and Quest for Power". In Kolrud, Kristine; Prusac, M. (eds.). Iconoclasm from antiquity to modernity. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. pp. 75–94. OCLC 841051222.

- Lambourne, Nicola (2001). War Damage in Western Europe: The Destruction of Historic Monuments During the Second World War. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1285-7.

- Narain, Harsh (1993). The Ayodhya Temple Mosque Dispute: Focus on Muslim Sources. Delhi: Penman Publishers.

- ISBN 81-85990-49-2

- Spicer, Andrew (2017). "Iconoclasm". S2CID 233344068.

- Topper, David R. Idolatry & Infinity: Of Art, Math & God. ISBN 978-1-62734-506-4.

- Velikov, Yuliyan (2011). Obrazŭt na Nevidimii︠a︡ : ikonopochitanieto i ikonootrit︠s︡anieto prez osmi vek [Image of the Invisible. Image Veneration and Iconoclasm in the Eighth Century] (in Bosnian). Veliko Tarnovo: Veliko Tarnovo University. OCLC 823743049.

- Weeraratna, Senaka ' Repression of Buddhism in Sri Lanka by the Portuguese' (1505 -1658)

- Teodoro Studita, Contro gli avversari delle icone, Emanuela Fogliadini (Prefazione), Antonio Calisi (Traduttore), Jaca Book, 2022, ISBN 978-8816417557

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1B: Pentagone E-M. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1993.

External links

- Iconoclasm in England, Holy Cross College (UK)

- Design as Social Agent at the ICA by Kerry Skemp, April 5, 2009

- Hindu temples destroyed by Muslim rulers in India

| Human- caused |

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | |||||||

![16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[35][36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG/441px-2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG)

![The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[72] The present temple was reconstructed in Chalukyan style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[73][74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg/420px-Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg)

![Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Warangal_fort.jpg/196px-Warangal_fort.jpg)

![Rani Ki Vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Rani_ki_vav1.jpg/402px-Rani_ki_vav1.jpg)

![Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0e/Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg/562px-Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg)