If and only if

↔⇔≡⟺

Logical symbols representing iff

In

In writing, phrases commonly used as alternatives to P "if and only if" Q include: Q is

Definition

The truth table of P Q is as follows:[7][8]

| F | F | T | F | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | F | T | F | F |

| T | F | F | F | F | T | F |

| T | T | F | T | T | T | T |

It is equivalent to that produced by the XNOR gate, and opposite to that produced by the XOR gate.[9]

Usage

Notation

The corresponding logical symbols are "", "",[6] and ,

Another term for the

In TeX, "if and only if" is shown as a long double arrow: via command \iff or \Longleftrightarrow.[12]

Proofs

In most

Origin of iff and pronunciation

Usage of the abbreviation "iff" first appeared in print in John L. Kelley's 1955 book General Topology.[13] Its invention is often credited to Paul Halmos, who wrote "I invented 'iff,' for 'if and only if'—but I could never believe I was really its first inventor."[14]

It is somewhat unclear how "iff" was meant to be pronounced. In current practice, the single 'word' "iff" is almost always read as the four words "if and only if". However, in the preface of General Topology, Kelley suggests that it should be read differently: "In some cases where mathematical content requires 'if and only if' and

Usage in definitions

Conventionally,

In terms of Euler diagrams

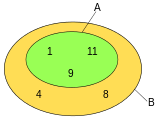

-

A is a proper subset of B. A number is in A only if it is in B; a number is in B if it is in A.

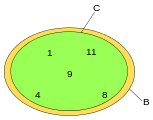

-

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B. A number is in B if and only if it is in C, and a number is in C if and only if it is in B.

Euler diagrams show logical relationships among events, properties, and so forth. "P only if Q", "if P then Q", and "P→Q" all mean that P is a subset, either proper or improper, of Q. "P if Q", "if Q then P", and Q→P all mean that Q is a proper or improper subset of P. "P if and only if Q" and "Q if and only if P" both mean that the sets P and Q are identical to each other.

More general usage

Iff is used outside the field of logic as well. Wherever logic is applied, especially in

The elements of X are all and only the elements of Y means: "For any z in the domain of discourse, z is in X if and only if z is in Y."

When "if" means "if and only if"

In their Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, Russell and Norvig note (page 282),[18] in effect, that it is often more natural to express if and only if as if together with a "database (or logic programming) semantics". They give the example of the English sentence "Richard has two brothers, Geoffrey and John".

In a database or logic program, this could be represented simply by two sentences:

- Brother(Richard, Geoffrey).

- Brother(Richard, John).

The database semantics interprets the database (or program) as containing all and only the knowledge relevant for problem solving in a given domain. It interprets only if as expressing in the metalanguage that the sentences in the database represent the only knowledge that should be considered when drawing conclusions from the database.

In first-order logic (FOL) with the standard semantics, the same English sentence would need to be represented, using if and only if, with only if interpreted in the object language, in some such form as:

- X(Brother(Richard, X) iff X = Geoffrey or X = John).

- Geoffrey ≠ John.

Compared with the standard semantics for FOL, the database semantics has a more efficient implementation. Instead of reasoning with sentences of the form:

- conclusion iff conditions

it uses sentences of the form:

- conclusion if conditions

to reason forwards from conditions to conclusions or backwards from conclusions to conditions.

The database semantics is analogous to the legal principle

See also

- Definition

- Equivalence relation

- Logical biconditional

- Logical equality

- Logical equivalence

- If and only if in logic programs

- Polysyllogism

References

- ^ "Logical Connectives". sites.millersville.edu. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-13-238034-8.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Iff." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Iff.html Archived 13 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9781441994790,

While it can be a real time-saver, we don't recommend it in formal writing.

- ISBN 9781482234312,

It is common in mathematical writing

- ^ a b Peil, Timothy. "Conditionals and Biconditionals". web.mnstate.edu. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Wolfram|Alpha

- ^ If and only if, UHM Department of Mathematics, archived from the original on 5 May 2000, retrieved 16 October 2016,

Theorems which have the form "P if and only Q" are much prized in mathematics. They give what are called "necessary and sufficient" conditions, and give completely equivalent and hopefully interesting new ways to say exactly the same thing.

- ^ "XOR/XNOR/Odd Parity/Even Parity Gate". www.cburch.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Equivalent". mathworld.wolfram.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Jan Łukasiewicz > Łukasiewicz's Parenthesis-Free or Polish Notation (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". plato.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "LaTeX:Symbol". Art of Problem Solving. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-387-90125-1

- ISBN 978-0-89871-420-3.

- ISBN 1568811667.

- ^ For instance, from General Topology, p. 25: "A set is countable iff it is finite or countably infinite." [boldface in original]

- ISBN 978-0-8218-0635-7

- OCLC 359890490.

- ^ Kowalski, R., Dávila, J., Sartor, G. and Calejo, M., 2023. Logical English for law and education. http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~rak/papers/Logical%20English%20for%20Law%20and%20Education%20.pdf In Prolog: The Next 50 Years (pp. 287-299). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.