Imwas

Imwas

عِمواس 'Amwas, Amwas | ||

|---|---|---|

Village | ||

Imwas, early 20th century | ||

| Etymology: possibly "thermal springs"[1] | ||

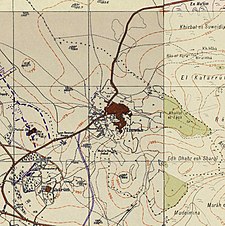

A series of historical maps of the area around Imwas (click the buttons) | ||

Geopolitical entity Mandatory Palestine | | |

| Subdistrict | Ramle | |

| Date of depopulation | 7 June 1967 | |

| Population | ||

| • Total | 2,015 | |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Expulsion by Israeli forces | |

| Current Localities | Canada Park | |

Imwas or Emmaus (

After the

Etymology

The name of the modern village was pronounced ʿImwās by its inhabitants.

In the time of

According to a tradition held by local fellahin in the 19th century, the village's name is related to an epidemic that killed the ancient Jewish inhabitants of the village, but they were miraculously brought back to life after Neby Uzair's visited the place and prayed to God to revive the victims. The fellahin described the pestilience as amm-mou-asa, which according to Clermont-Ganneau, roughly means "it was extended generally and was an affliction". Clermont-Ganneau thought this local etymology was "evidently artificial".[8][9]

History

Classical antiquity

Emmaus is also mentioned in the first

Edward Robinson relates that its inhabitants were enslaved by Gaius Cassius Longinus while Josephus relates that the city, called Άμμoὺς, was burned to the ground by Publius Quinctilius Varus after the death of Herod the Great in 4 BCE.[10][11]

Imwas has been identified as the site of ancient Emmaus, where according to the Gospel of Luke (24:13-35), Jesus appeared to a group of his disciples, including Cleopas, after his death and resurrection.[12]

Reduced to a small market town, its importance was recognized by the Emperor

Described by Eusebius in his Onomasticon, Jerome is also thought to have referred to the town and the building of a shrine-church therein, when he writes that the Lord "consecrated the house of Cleopas as a church."[16] In the 5th century, a second tradition associated with Emmaus emerges in the writings of Sozomen, who mentions a fountain outside the city where Jesus and his disciples bathed their feet, thus imbuing it with curative powers.[12]

Arab caliphates era

After the

The governmental framework of the Byzantine rule was preserved, though a commander-in-chief/governor-general was appointed from among the new conquerors to head the government, combining executive, judicial and military roles in his person.[17]

In 639, the

In 723, Saint

By the 9th century, the administrative districts had been redrawn and Imwas was the capital of a sub-district within the larger district of Jund Filastin.[23] The geographer al-Maqdisi (c. 945-1000) recalls that ʿImwas had been the capital of its province, while noting, "that the population [was] removed therefrom to be nearer to the sea, and more in the plain, on account of the wells."[24]

By 1009, the church in Imwas had been destroyed by Yaruk, the governor of

Crusader era

The identification of Biblical Emmaus with two villages in the 12th century has led to some confusion among modern historians when apprehending historical documents from this time. Generally speaking, however, Abu Ghosh was referred to by the Latin Biblical name for Emmaus, Castellum Emmaus, whereas Imwas was referred to simply as Emmaus. In 1141,

Imwas was likely abandoned by Crusaders in 1187 and unlike the neighboring villages of Beit Nuba, Yalo, Yazur and Latrun, it is not mentioned in chronicles describing the Third Crusade of 1191-2, and it is unclear whether it was reoccupied by the Hospitallers between 1229 and 1244.[25] The village was re-established just north of where the church had been located.[25]

Mamluk era

Maqam Sheikh Mu'alla had an endowment text (now lost), dating it to 687 AH/1289-1290 CE.[33] Clermont-Ganneau described it:

The most important, and most conspicuous Mussulman sanctuary in 'Amwas is that which stands on the hill some 500 metres to the south of the village. It appears on the P.E.Fund Map under the name of Sheikh Mo'alla, a name which is interpreted in the name lists by "lofty." I have heard the name pronounced Ma'alleh, and also Mu'al, or Mo'al; but these are merely shorter or less accurate forms; the complete name, as I have on several occasions noted, is Sheikh Mu'al iben Jabal. Although they do not know anything about its origin, the

Beladhory and Yakut, call the place where Mu'adh ben Jabal died and was buried, Ukhuana...... I have established the exact position of Ukhuana, and its identity with the Cauan of the Crusaders, in my Etudes d'Archeologie Orientale, Vol. II, p. 123.) .....We may presume that originally this monument was merely commemorative, and that local tradition has at last wrongly ended in regarding it as the real tomb of this celebrated personage, inferring from his having succumbed to the 'Plague of 'Amwas' that he died and was buried at 'Amwas itself. However, the mistake of the legend on this point must be a very ancient one, for as early as the twelfth century, Aly el Herewy has the following passage : " One sees at 'Amwas the tombs of a great number of companions of the prophets and of tabis who died of the Plague. Among them (sic) is mentioned 'Abd er Rahman ibn {sic) Mu'adh ben Jabal and his children. ...[34]

Ottoman era

Imwas came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire in the early 16th century and by the end of that century, the church built by the Crusaders had been converted into a

Edward Robinson visited Imwas during his mid-19th century travels in Ottoman Syria and Palestine. He describes it as "a poor hamlet consisting of a few mean houses." He also mentions that there are two fountains of living water and that the one lying just beside the village must be that mentioned by Sozomen in the 5th century, Theophanes in the 6th, and by Willibald in the 8th.[36] The ruins of the "ancient church" are described by Robinson as lying just south of the built-up area of the village at that time.[36]

In 1863

Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau also visited Imwas in the late 19th century and describes a local tradition centered around a bathhouse dating to the Roman era. The upper part of the structure, which protruded above the ground, was known to locals as "Sheikh Obaid" and was considered to be the burial place of Abu Ubayd who succumbed to the plague in 639. The site served as both a religious sanctuary and cemetery until the town's depopulation in 1967.[21][38]

In 1875, the

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Imwas as an adobe village, of moderate size.[40]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Imwas had a population of 824, all Muslim.[41] This had increased by the time of the 1931 census to 1,029, 2 Christians and 1,027 Muslim, in 224 houses.[42]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Imwas was 1,450, all Muslims,[43] while the total land area was 5,151 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[44] Of this, 606 dunams were allocated for plantations and irrigable land, 3,612 for cereals,[43][45] while 148 dunams were classified as built-up areas.[43][46] By 1948, the population had dwindled to 1,100 Arabs.[47]

Jordanian rule

During the

After the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Imwas came under Jordanian control.

The Jordanian census of 1961 found 1,955 inhabitants in Imwas.[49]

Israeli rule

The town, defended by a few Jordanian and Egyptian units,[

'terms of disappointment, terms of a long and painful account, which has now been settled to the last cent. Houses suddenly left. Intact. With their potted geraniums, their grapevines climbing up the balconies. The smell-of wood-burning ovens still in the air. Elderly people who have nothing more to lose, slowly straggling along.,'[50]

In August of that year, villagers were told that they return could pick up their stored harvests with trucks.[51] The residents of the three villages then formed a committee to negotiate their return. The villagers' request that Israel allow their leaders, who had fled to Amman, to return and negotiate on their behalf, was turned down by Dayan.[51] Israel offered monetary compensation for the destruction of homes and the expropriation of lands. One committee leader, the father of Abu Gaush replied:

"We will not accept all the money in the world for one dunam in Imwas, and we will not accept one dunum in heaven for one dunam in Inwas!"[51]

According to his son, he was told by his Israeli interlocutors that he had three choices: to share the fate of Sheikh Abdul Hameed Al Sayeh, the first Palestinian to be exiled by Israel after the beginning of the 1967 occupation, after he spoke up for the inalienable right of return of Palestinians; or he could choose to go to prison, or, finally, he could suck on something sweet and keep quiet;[51] In all cases no one was allowed to return.[51] One descendant of the expelled villagers said her father told her they were threatened with prison if they did not agree to compensation [51][52][53][54][55] An Imwas Human Society now campaigns for the expelled villagers' rights and publicizes what they call the war crimes committed in the Latrun Enclave.[51]

In 1973 the Jewish National Fund in Canada raised $5 million to establish a picnic park for Israelis in the area,[51] which it created and still maintains. It descrfibes the area as:-

"one of the largest parks in Israel, covering an area of 7,500 acres in the biblical Ayalon Valley. At peak season, some 30,000 individuals visit the site each day,. enjoying its many play and recreational facilities and installations."[51]

Since 2003, the Israeli

Artistic representations

Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour made Imwas the subject of one of his paintings. The work, named for the village, was one of a series of four on destroyed Palestinian villages that he produced in 1988; the others being Yalo, Bayt Dajan and Yibna.[59]

The destruction of Imwas and the other Latrun villages of

Emwas, restoring memories is a recent documentary film in which the filmmaker makes a 3D model of the town using expertise and interviews with people who survived the exodus.[61]

See also

- List of villages depopulated during the Arab-Israeli conflict

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 283

- ^ Wareham and Gill, 1998, p. 108.

- Julius Africanusand Origen. It is also supported by many Biblical commentaries, some of which are as old as the fourth or the fifth century; in these the Emmaus of the Gospel is said to have stood at 160 stadia from Jerusalem, the modern 'Am'was being at 176 stadia. In spite of its antiquity, this tradition does not seem to be well founded. Most manuscripts and versions place Emmaus at only sixty stadia from Jerusalem, and they are more numerous and generally more ancient than those of the former group. It seems, therefore, very probable that the number 160 is a correction of Origen and his school to make the Gospel text agree with the Palestinian tradition of their time. Moreover, the distance of 160 stadia would imply about six hours' walk, which is inadmissible, for the Disciples had only gone out to the country and could return to Jerusalem before the gates were shut (Mark 16:12; Luke 24:33). Finally, the Emmaus of the Gospel is said to be a village, while 'Am'was was the flourishing capital of a 'toparchy'. Josephus (Ant. Jud., VII, vi, 6) mentions at sixty stadia from Jerusalem a village called Ammaus, where Vespasian and Titus stationed 800 veterans. This is evidently the Emmaus of the Gospel. But it must have been destroyed at the time of the revolt of Bar-Cocheba (A.D. 132-35) under Hadrian, and its site was unknown as early as the third century. Origen and his friends merely placed the Gospel Emmaus at Nicopolis, the only Emmaus known at their time. The identifications of Koubeibeh, Abou Gosh, Koulonieh, Beit Mizzeh, etc. with Emmaus, as proposed by some modern scholars, are inadmissible.

- ISBN 978-0-345-46431-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharon, 1997, p. 79

- ^ Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1899). Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873–1874. Vol. 1. p. 490.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP III, p. 36-37

- ^ C. Clermont-Ganneau, "Letters: VII-X," Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 6.3 (July 1874): p. 162

- ^ Conder, C. R. (Claude Reignier); Kitchener, Horatio Herbert Kitchener; Palmer, Edward Henry; Besant, Walter (1881–1883). The survey of western Palestine : memoirs of the topography, orography, hydrography, and archaeology. Robarts - University of Toronto. London : Committee of the Palestine exploration fund. p. 66.

- ^ a b c Robinson and Smith, 1856, p. 147

- ^ a b Bromiley, 1982, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pringle, 1993, p. 52

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War Bk 7,6:6.

- ^ a b Negev and Gibson, 2005, p. 159.

- ISBN 978-90-04-10833-2.

- ISBN 978-0-521-39036-1.

- ^ a b Hitti, 2002, p. 424]

- ^ Hitti, 2002, p. 425

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, 1916, p. 215

- ^ Bray, 2004, p. 40

- ^ a b Sharon, 1997, p. 80

- ^ a b c Thiede and D'Ancona, 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Gil, 1997, p. 111

- ^ Al-Maqdisi quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.393.

- ^ a b c d Pringle, 1993, p. 53

- ^ Brownrigg, 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 50, No 201; cited in Pringle, 1993, p. 53

- ^ de Roziére, 1849, pp. 219-220, No. 117; cited in Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 51, No 205; cited in Pringle, 1993, p. 53

- ^ Röhricht, 1893, RRH, pp. 61-62, No 244; p. 65, No 257; p. 69, No 274; all cited in Pringle, 1993, p. 53

- ^ Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 172, No 649; cited in Pringle, 1993, p. 53

- ^ Levy, 1998, p. 508.

- ^ Thiede and D'Ancona, 2005, p. 60

- ^ Sharon, 1997, p. 84

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, 1899, ARP 1, pp. 492-493

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 153

- ^ a b Robinson and Smith, 1856, p. 146

- ^ Guérin, 1868, pp. 293-308

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, 1899, pp. 483-493

- ^ Schick, 1884, p. 15; cited in Driver et al., 2006, p. 325

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 14

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 15

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 29

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 66

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 115

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 165

- OCLC 610327173.

- ^ Morris, 2008, see Latrun and Imwas in the index.

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 24

- ^ a b c d e Tom Segev, 1967, Abacus Books 2007 pp.489-490.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rich Wiles, "Behind the Wall: Life, Love, and Struggle in Palestine," Potomac Books, Inc., 2010, pp. 17-24.

- ^ a b Oren, 2002, p. 307

- ^ a b Mayhew and Adams, 2006.

- ^ Segev, 2007, pp. 407–409

- ^ "Interview: Ahmad Abughoush: "Imwas : Canada Park's Concealed Crime "". Archived from the original on 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- ^ a b Zafrir Rinat (13 June 2007). "Out of sight maybe, but not out of mind". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ High Court Petition on Canada Park[usurped], Zochrot

- ^ Tour to Imwas[usurped], Zochrot

- ^ Ankori, 2006, p. 82

- The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptimist, Arabia Books, London, 2010 ( Chapter 36)

- ^ Maude Girard, 25 May 2018, fr:Orient XXI, Le festival Ciné Palestine s’engage auprès des réalisateurs

Bibliography

- Philip Khuri Hitti. New York: Columbia University.

- ISBN 1-86189-259-4.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Bray, R.S. (2004). Armies of Pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History. James Clarke & Co. ISBN 9780227172407.

- ISBN 9780802837820.

- Brownrigg, Ronald (2001). Who's Who in the New Testament. Routledge. ISBN 9780415260367.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1899). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873–1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 1. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 63 -81)

- ISBN 0-860549-05-4. (pp. 890–1)

- Driver, S. R.; Wardrop, Margery; Lake, Kirsopp (2006). Studies in Biblical and Patristic Criticism: Or Studia Biblica Et Ecclesiastica. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 9781593334703.

- ISBN 9780521599849.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- ISBN 1931956618.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from AD. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9.

- ISBN 9780826469960.

- ISBN 1-904955-19-3.

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon (2005). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826485717.

- ISBN 0-19-515174-7.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ISBN 0-521-39036-2.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (pp. 363-364)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (p. 30)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- E. de Roziére, ed. (1849). Cartulaire de l'église du Saint Sépulchre de Jérusalem: publié d'après les manuscrits du Vatican (in Latin and French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schick, C. (1884). "Das altchristliche Taufhaus neben der Kirche in Amwas". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 7. Leipzig: 15–17.

- Segev, S. (1967). A Red Sheet: the Six Day War.

- ISBN 978-0-8050-7057-6.

- ISBN 90-04-10833-5.

- ISBN 9780826467973.

- Wareham, Norman; Gill, Jill (1998). Every Pilgrim's Guide to the Holy Land. SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd. ISBN 9781853112126.

External links

![]() Media related to Imwas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Imwas at Wikimedia Commons

- Welcome To 'Imwas

- Imwas, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Interview: Ahmad Abughoush: "Imwas : Canada Park's Concealed Crime " BADIL