Index Librorum Prohibitorum

Catholic Counter-Reformation |

|

| Catholic Reformation and Revival |

|

The Index Librorum Prohibitorum (English: Index of Forbidden Books) was a changing list of publications deemed

The Index was active from 1560 to 1966.[2][3][4][page needed] It banned thousands of book titles and blacklisted publications, including the works of Europe's intellectual elites.[5][6][7]

The Index condemned religious and secular texts alike, grading works by the degree to which they were deemed to be repugnant or dangerous to the church at the time.

Background and history

European restrictions on the right to print

The historical context in which the Index appeared involved the early restrictions on printing in Europe. The refinement of

In the 16th century, both the churches and governments in most European countries attempted to regulate and control printing because it allowed for the rapid and widespread circulation of ideas and information. The

The early versions of prohibition indexes began to appear from 1529 to 1571. In the same time frame, in 1557 the

The French crown also tightly controlled printing, and the printer and writer Étienne Dolet was burned at the stake for atheism in 1546. The 1551 Edict of Châteaubriant comprehensively summarized censorship positions to date, and included provisions for unpacking and inspecting all books brought into France.[17][18] The 1557 Edict of Compiègne applied the death penalty to heretics and resulted in the burning of a noblewoman at the stake.[19] Printers were viewed as radical and rebellious, with 800 authors, printers and book dealers being incarcerated in the Bastille.[20] At times, the prohibitions of church and state followed each other, e.g. René Descartes was placed on the Index in the 1660s and the French government prohibited the teaching of Cartesianism in schools in the 1670s.[16][page needed]

The Copyright Act 1710 in Britain, and later copyright laws in France, eased this situation. Historian Eckhard Höffner claims that copyright laws and their restrictions acted as a barrier to progress in those countries for over a century, since British publishers could print valuable knowledge in limited quantities for the sake of profit. The German economy prospered in the same time frame since there were no restrictions.[21][22][page needed]

Early indexes (1529–1571)

The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529); Venice (1543) and Paris (1551) under the terms of the Edict of Châteaubriant followed this example. By the mid-century, in the tense atmosphere of wars of religion in Germany and France, both Protestant and Catholic authorities reasoned that only control of the press, including a catalogue of prohibited works, coordinated by ecclesiastic and governmental authorities, could prevent the spread of heresy.[23]

Paul F. Grendler (1975) discusses the religious and political climate in Venice from 1540 to 1605. There were many attempts to censor the Venetian press, which at that time was one of the largest concentrations of printers. Both church and government held to a belief in censorship, but the publishers continually pushed back on the efforts to ban books and shut down printing. More than once the index of banned books in Venice was suppressed or suspended because various people took a stand against it.[24]

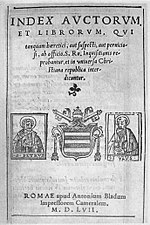

The first Roman Index was printed in 1557 under the direction of Pope Paul IV (1555–1559), but then withdrawn for unclear reasons.[25] In 1559, a new index was finally published, banning the entire works of some 550 authors in addition to the individual proscribed titles:[25][note 1] "The Pauline Index felt that the religious convictions of an author contaminated all his writing."[23] The work of the censors was considered too severe and met with much opposition even in Catholic intellectual circles; after the Council of Trent had authorised a revised list prepared under Pope Pius IV, the so-called Tridentine Index was promulgated in 1564; it remained the basis of all later lists until Pope Leo XIII, in 1897, published his Index Leonianus.

The

Sacred Congregation of the Index (1571–1917)

| Part of a series on the |

| Roman Curia |

|---|

|

|

Catholicism portal |

In 1571, a special congregation was created, the Sacred Congregation of the Index, which had the specific task to investigate those writings that were denounced in Rome as being not exempt of errors, to update the list of Pope Pius IV regularly and also to make lists of required corrections in case a writing was not to be condemned absolutely but only in need of correction; it was then listed with a mitigating clause (e.g., donec corrigatur ('forbidden until corrected') or donec expurgetur ('forbidden until purged')).[citation needed]

Several times a year, the congregation held meetings. During the meetings, they reviewed various works and documented those discussions. In between the meetings was when the works to be discussed were thoroughly examined, and each work was scrutinized by two people. At the meetings, they collectively decided whether or not the works should be included in the Index. Ultimately, the pope was the one who had to approve of works being added or removed from the Index. It was the documentation from the meetings of the congregation that aided the pope in making his decision.[27]

This sometimes resulted in very long lists of corrections, published in the Index Expurgatorius, which was cited by

An update to the Index was made by Pope

The

Holy Office (1917–1966)

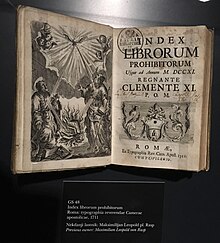

While individual books continued to be forbidden, the last edition of the Index to be published appeared in 1948. This 20th edition

Among the denounced works of the period was the Nazi philosopher

Abolition (1966)

On 7 December 1965, Pope Paul VI issued the motu proprio

A June 1966 Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

The

Scope and impact

Censorship and enforcement

The Index was not simply a reactive work. Roman Catholic authors had the opportunity to defend their writings and could prepare a new edition with necessary corrections or deletions, either to avoid or to limit a ban. Pre-publication censorship was encouraged.[citation needed]

The Index was enforceable within the Papal States, but elsewhere only if adopted by the civil powers, as happened in several Italian states.[40] Other areas adopted their own lists of forbidden books. In the Holy Roman Empire book censorship, which preceded the publication of the Index, came under the control of the Jesuits at the end of the 16th century, but had little effect, since the German princes within the empire set up their own systems.[41] In France it was French officials who decided what books were banned[41] and the Church's Index was not recognized.[42] Spain had its own Index Librorum Prohibitorum et Expurgatorum, which corresponded largely to the Church's,[43] but also included a list of books that were allowed once the forbidden part (sometimes a single sentence) was removed or "expurgated".[44]

Continued moral obligation

On 14 June 1966, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith responded to inquiries it had received regarding the continued moral obligation concerning books that had been listed in the Index. The response spoke of the books as examples of books dangerous to faith and morals, all of which, not just those once included in the Index, should be avoided regardless of the absence of any written law against them. The Index, it said, retains its moral force "inasmuch as" (quatenus) it teaches the conscience of Christians to beware, as required by the natural law itself, of writings that can endanger faith and morals, but it (the Index of Forbidden Books) no longer has the force of ecclesiastical law with the associated censures.[45]

The congregation thus placed on the conscience of the individual Christian the responsibility to avoid all writings dangerous to faith and morals, while at the same time abolishing the previously existing ecclesiastical law and the relative censures,[46] without thereby declaring that the books that had once been listed in the various editions of the Index of Prohibited Books had become free of error and danger.

In a letter of 31 January 1985 to Cardinal Giuseppe Siri, regarding the book The Poem of the Man-God, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (then Prefect of the Congregation, who later became Pope Benedict XVI), referred to the 1966 notification of the Congregation as follows: "After the dissolution of the Index, when some people thought the printing and distribution of the work was permitted, people were reminded again in L'Osservatore Romano (15 June 1966) that, as was published in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis (1966), the Index retains its moral force despite its dissolution. A decision against distributing and recommending a work, which has not been condemned lightly, may be reversed, but only after profound changes that neutralize the harm which such a publication could bring forth among the ordinary faithful."[47]

Changing judgments

The content of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum saw deletions as well as additions over the centuries. Writings by

Some of the scientific theories contained in works in early editions of the Index have long been taught at

Listed works and authors

Noteworthy figures on the Index include

In many cases, an author's opera omnia (complete works) were forbidden. However, the Index stated that the prohibition of someone's opera omnia did not preclude works that were not concerned with religion and were not forbidden by the general rules of the Index. This explanation was omitted in the 1929 edition, which was officially interpreted in 1940 as meaning that opera omnia covered all the author's works without exception.[58]

Cardinal Ottaviani stated in April 1966 that there was too much contemporary literature and the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith could not keep up with it.[59]

See also

- List of authors and works on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum

- Archive of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

- Book censorship

- Clericalism

- Nazi book burnings, some of the books mentioned in the list were burned by the NSDAP

- Index of Repudiated Books

- Literary inquisition

Notes

References

- ISBN 978-0-52139748-3) pp. 45–46

- ^ The 20th and final edition of the Index appeared in 1948; the Index was formally abolished on 14 June 1966 by Pope Paul VI. "Notification regarding the abolition of the Index of books". 14 June 1966.

- ISBN 082450013X, p. 168

- ^ Kusukawa, Sachiko (1999). "Galileo and Books". Starry Messenger.

- S2CID 144325885.

- ^ Anastaplo, George. "Censorship". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Hilgers, Joseph (1908). "Censorship of Books". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Lyons, Martyns (2011). A Living History. Los Angeles. pp. Chapter 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Giannini, Massimo Carlo. "Robert Bellarmine: Jesuit, Intellectual, Saint". Pontifical Gregorian University. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Cardinal Saraiva calls new blessed Antonio Rosmini "giant of the culture"". Catholic News Agency.

- ^ Index Librorum Prohibitorum, 1559, Regula Quarta ("Rule 4")

- ISBN 978-0-8020-6041-9p. 124

- ISBN 978-0-19-926339-4.

- ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ^ "The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers". Shakespeare Documented. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ ISBN 1-4051-2154-8

- ISBN 0-313-31034-3pp. 31–32

- ISBN 0-521-29955-1page 328

- ISBN 0-631-22729-6p. 241

- ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ^ Thadeusz, Frank (18 August 2010). "No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany's Industrial Expansion?". Der Spiegel – via Spiegel Online.

- ISBN 3-930893-16-9

- ^ a b c Schmitt 1991:45.

- S2CID 151934209.

- ^ a b Brown, Horatio F. (1907). Studies in the History of Venice (Vol. 2). New York, E.P. Dutton and company.

- ISBN 978-90-0404259-9), p. 90.

- ^ Heneghan, Thomas (2005). "Secrets Behind The Forbidden Books". America. 192 (4). Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^

Green, Jonathan; Karolides, Nicholas J. (2005), Encyclopedia on Censorship, Facts on File, Inc, p. 257, ISBN 9781438110011

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Censorship of Books". www.newadvent.org.

- ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4, p. 83

- ^ America Magazine Feb 7, 2005 [1]

- ^ "Index Librorum Prohibitorum | Roman Catholicism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "The works appearing on the Index are only those that ecclesiastical authority was asked to act upon" (Encyclopædia Britannica: Index Librorum Prohibitorum).

- ^ "The entanglement of Church and state power in many cases led to overtly political titles being placed on the Index, titles which had little to do with immorality or attacks on the Catholic faith. For example, a history of Bohemia, the Rervm Bohemica Antiqvi Scriptores Aliqvot [...] by Marqvardi Freheri (published in 1602), was placed on the Index not for attacking the Church, but rather because it advocated the independence of Bohemia from the (Catholic) Austro-Hungarian Empire. Likewise, The Prince by Machiavelli was placed in the Index in 1559 after it was blamed for widespread political corruption in France (Curry, 1999, p. 5)" (David Dusto, Index Librorum Prohibitorum: The History, Philosophy, and Impact of the Index of Prohibited Books). Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-3-03911-904-2; p. 122

- ^ Paul VI, Pope (7 December 1965). "Integrae servandae". vatican.va. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ L'Osservatore della Domenica, 24 April 1966, p. 10.

- ^ Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (14 June 1966). "Notification regarding the abolition of the Index of books". vatican.va. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ a b c "Code of Canon Law: text - IntraText CT". www.intratext.com.

- ISBN 978-9-00422248-9), p. 236

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85984108-2), pp. 245–246

- ISBN 978-0-82045768-0), p. 11

- ISBN 978-0-52139748-3), p. 48

- ^ "Index librorum prohibitorum et expurgatorum". apud Ludouicum Sanchez. 17 October 1612 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Haec S. Congregatio pro Doctrina Fidei, facto verbo cum Beatissimo Patre, nuntiat Indicem suum vigorem moralem servare, quatenus Christifidelium conscientiam docet, ut ab illis scriptis, ipso iure naturali exigente, caveant, quae fidem ac bonos mores in discrimen adducere possint; eundem tamen non-amplius vim legis ecclesiasticae habere cum adiectis censuris" (Acta Apostolicae Sedis 58 (1966), p. 445). Cf. Italian text published, together with the Latin, on L'Osservatore Romano of 15 June 1966)

- ^ "Dictionary: POST LITTERAS APOSTOLICAS". www.catholicculture.org.

- ^ "Poem of the Man-God". EWTN. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Encyclical Fides et raptio, 74

- ISBN 0-268-03483-4. pp. 307, 347

- ISBN 0-268-03483-4)

- ^ Stead, William Thomas (1902). "The Index Expurgatorius". The Review of Reviews. 26: 498. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Gifford, William (1902). "The Roman Index". The Quarterly Review. 196: 602–603. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Catholic Church (1569). Index Librorum Prohibitorum cum Regulis confectis per Patres a Tridentina Synodo delectos authoritate [...] Pii IIII. comprobatus. Una cum iis qui mandato Regiae Catholicae Majestatis et [...] Ducis Albani, Consiliique Regii decreto prohibentur, etc. Leodii. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ISBN 9782762200454. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ISBN 9780524007792. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Hilgers, Joseph (1904). Der Index der verbotenen Bücher. In seiner neuen Fassung dargelegt und rechtlich-historisch gewürdigt. Freiburg in Breisgau: Herder. pp. 145–150.

- ^ Rafael Martinez, professor of the philosophy of science at the Santa Croce Pontifical University in Rome, in speech reported on Catholic Ireland net Archived 7 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 26 May 2009

- ISBN 2-600-00818-7), p. 36

- L'Osservatore della Domenica, 24 April 1966, p. 10.

Further reading

- J. Martínez de Bujanda's Index Librorum Prohibitorum, 1600–1966 lists the authors and writings in the successive editions of the Index,[1] while Miguel Carvalho Abrantes's Why Did The Inquisition Ban Certain Books?: A Case Study from Portugal tries to understand why certain books were forbidden based on a Portuguese edition of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum from 1581.[2][page needed]

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Facsimile of the 1559 index Archived 10 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- List of famous authors in the index

- "Index of Prohibited Books", The Catholic Encyclopedia (Volume VII, 1910): "The first Roman Index of Prohibited Books (Index librorum prohibitorum), published in 1559 under Paul IV, was very severe, and was therefore mitigated under that pontiff by decree of the Holy Office of 14 June of the same year. It was only in 1909 that this Moderatio Indicis librorum prohibitorum (Mitigation of the Index of Prohibited Books) was rediscovered in Codex Vaticanus lat. 3958, fol. 74, and was published for the first time."

- The ten "tridentine" rules on the censorship of books (English)

- The papal constitution Sollicita ac provida regulating the work of the Congregations of the Holy Office and of the Index (Latin) Archived 28 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Vatican opens up secrets of Index of Forbidden Books, Dec 22, 2005

- Secrets Behind The Forbidden Books – America, 7 February 2005

- An index of prohibited books, by command of the present pope, Gregory XVI in 1835; being the latest specimen of the literary policy of the Church of Rome, Joseph Mendham, London: Duncan and Malcolm, 1840. Also at the archive.org.

- The Roman Index of Forbidden Books: Briefly explained for Catholic Booklovers and Students at Project Gutenberg (History and commentary of the index from 1909)

- ISBN 978-2-60000818-1)

- ISBN 978-1689144377)