Indian Australians

Indian Australians or Indo-Australians are

Indians are the youngest average age (34 years) and the fastest growing community both in terms of absolute numbers and percentages in Australia.[5]

In 2017–18

As of 2016, Indians were the highest educated migrant group in Australia with 54.6% of Indians in Australia having a bachelor's or higher degree, more than three times Australia's national average.[9]

The long history of Indian migration to Australia has progressed "from 18th-century sepoys and lascars (soldiers and sailors) aboard visiting European ships, through 19th-century migrant labourers and the 20th century's hostile policies to the new generation of skilled professional migrants of the 21st century... India became the largest source of skilled migrants in the 21st century."[10]

History

Pre-history migration of Indians (2300 BCE–2000 BCE)

A study of

Indian connection with European exploration of Australia (1627–1787)

Most early explorations of Australia by various European colonial powers had an Indian connection. Indians had been employed for a long time on the European ships trading in

Colonial era (1788–1900)

Indian immigration from

The people of the first British fleet to establish a new colony, which landed on 26 January 1788, included seamen, marines and their families, government officials, and a large number of convicts, including women and children. All had been tried and convicted in Great Britain and almost all of them in England. However, many are known to have come to England from other parts of Great Britain and, especially, from Ireland; at least 12 were identified as black (born in India, Britain, Africa, the West Indies, North America, or a European country or its colony).[26]: 421–4 These colonies multiplied and expanded to include whole Australia, various Islands in Oceania, initially colonies were established under the British Indian Empire including New Zealand which was administered as part of New South Wales until 1841.

Between 1788 and 1868 on board 806 ships in all about 164,000 convicts were transported to the Australian colonies,

In the late 1830s, more Indians started to arrive in Australia as

From the 1860s, Indians, most of them

Between 1860s to 1900 period when small groups of

Since Federation (1901–present)

During the White Australia policy (1901–1973)

From federation in 1901 until the 1973 immigration of non-Europeans, including Indians, into Australia was restricted due to the enactment of the

During

During

Since the end of the White Australia policy (1973–present)

The end of White Australia policy saw a boom in migration of middle-class skilled professionals, by 2016 over 2 in every 3 migrants who arrived were skilled professionals mainly from India, UK, China, South Africa and Philippines, "to work as doctors and nurses, human-resources and marketing professionals, business managers, IT specialists, and engineers...who were not fleeing war or poverty. The Indians in Australia are predominantly male, while the Chinese are majority female." Indians are the largest migrant ethnic group in Melbourne and Adelaide, fourth largest in Brisbane, and likely to jump from third place to second place in Sydney by 2021. In Melbourne, the suburbs of Docklands, Footscray, Sunshine, Truganina, Tarneit and Pakenham have higher concentration of Indians specially the students. In Sydney, Parramatta [and neighbouring suburbs such as Harris Park and Westmead, etc.] have higher concentration of migrants.[55] By 2019, the number of Indians grew at nine times the annual national average growth, and number of overseas student visas and post-study work visas also exploded.[56]

Between 2007 and 2010, the

Demographics

783,958 persons declared Indian ancestry (whether alone or in combination with another ancestry) at the 2021 census, representing 3.1% of the Australian population.[1]

In 2019, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 721,050 Australian residents were born in India.[3][65]

At the 2021 census the states with the largest number of people nominating Indian ancestry were: New South Wales (350,770), Victoria (250,103), Queensland (93,648), Western Australia (77,357) and South Australia (43,598).[66]

In 2009 there were an additional 90,000 Indian students studying at Australian tertiary institutions according to Prime Minister Rudd.[67]

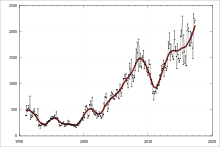

Historical population trends

This table only reflects the people who were born in India, and not all the people who have the Indian ancestry such as the second generation Indian Australians or the first generation Indian Australians from Indian diaspora nations e.g. Fiji, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Suriname, Guyana, etc. Prior to 1947 India's Independence and simultaneous partition, the

| Year | Born in India | All overseas born | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of Indians among overseas born | Number | % of all overseas born in total population of Australia | and comments | ||

| 26 January 1788[26][27][28][29] | 12* | People of the first British fleet included 12 non-European people including some Indians. | ||||

| 1881[25] | 998 | |||||

| 1891[25] | 1700 | |||||

| 1901[42] | 4700 to 7600 | Introduction of White Australia policy led to reduction of Indians. | ||||

| 1911[43] | 3698 | |||||

| 1921[43] | 2200 | |||||

| Before 1941[68] | 170 | 0.1 | 16,681 | 0.3 | ||

| 1941–1950[68] | 2,027 | 0.7 | 106,647 | 2.0 | ||

| 1951–1960[68] | 1,697 | 0.6 | 375,076 | 7.1 | ||

| 1961–1970[68] | 10,319 | 3.5 | 642,355 | 12.1 | End of the White Australia policy in 1973. | |

| 1971–1980[68] | 11,595 | 3.9 | 571,828 | 10.8 | ||

| 1981–1990[68] | 17,659 | 6.0 | 782,926 | 14.8 | ||

| 1991–2000[68] | 36,765 | 12.4 | 786,777 | 14.9 | ||

| 2001–2005[68] | 48,949 | 16.6 | 581,597 | 11.0 | ||

| 2006–2011[68] | 159,326 (390,894) | 52.9 | 1,190,322 | 22.5 | 390,894 are ethnic Indian and among them 295,362 were born in India. | |

| 2011–2016[3][5][69] | 592,000 (619,164) | 619,164 (2.8% of Australian population) are ethnic Indian and among them 592,000 (2.4% of Australian population) were born in India. | ||||

| 2016–2021 | ||||||

| 2022–2027 | ||||||

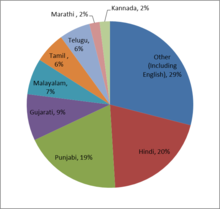

Indian languages

Religion

With 92.6% of Indian Australians being religious, Indian Australians are a much more religious group than Australia as a whole (Australia being 46.1% irreligious),[72][73] but less religious than India itself which is 99.7% religious.[74] While India is 79.8% Hindu, 14.2% Muslim, 2.3% Christian, and 1.7% Sikh, Indian Australians are 45.0% Hindu, 20.8% Sikh, 10.3% Catholic, and 6.6% Muslim, with a significant over-representation of Sikhs and Christians and an under-representation of Hindus and Muslims.

Socio-economic status

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2020) |

In 2016, it was revealed 54.6% of Indian migrants in Australia hold a bachelor's degree or a higher educational degree, more than three times Australia's national average of 17.2% in 2011, making them the most educated demographic group in Australia.[9]

India annually contributes the largest number of migrants to both Australia and New Zealand. According to census figures from 2016, among India-born residents in Australia, the median income was $785, higher than the corresponding figure for all overseas-born residents at $615, and all Australia-born residents at $688.[75]

In popular media

"Indians and the Antipodes: Networks, Boundaries and Circulation" 2018 book edited by Sekhar Bandyopadhyay and Jane Buckingham "is the first book that seeks to juxtapose histories of Indian migration to Australia and New Zealand in a comparative framework to show their interconnectedness as well as dissimilarities. Side by side with stories of collective suffering and struggles of the diaspora, it focuses on individual resilience, enterprise and social mobility. It analyses 'White Australia' and 'White New Zealand' policies of the early twentieth century to point to their interconnected histories. It also looks critically at the more recent migration, its changing nature and the challenges it poses to both the migrant communities and the host societies."[76]

Notable Indian Australians

Indian ancestry

- Anupam Sharma, Filmmaker, Australia Day Ambassador, film entrepreneur

- Astra Sharma, Tennis player

- Man Booker Prize

- Purushottama Bilimoria, Professor at Deakin University

- Anusha Dandekar, Actress

- Shibani Dandekar, Actress

- Chennupati Jagadish AC, pioneer in nanotechnology

- Zinnia Kumar Scientist and International Fashion Model

- Kersi Meher-Homji, Journalist and Author

- Mahesh Jadu, Actor

- Maria Thattil, Activist, Beauty Queen and Model of South Indian descent who was crowned Miss Universe Australia 2020 and placed Top 10 at Miss Universe 2020

- Marc Fennell, film critic, technology journalist, radio personality, author and television presenter

- Tharini Mudaliar, Singer and Actress who played a role in The Matrix Revolutions and Xena: Warrior Princess

- Indira Naidoo, Newsreader

- Neel Kolhatkar, Comedian

- Pankaj Oswal, controversial businessman, accused of embezzlement

- Vimala Raman, Actress

- Chandrika Ravi, Actress

- Pallavi Sharda, Actress

- Partho Sen-Gupta, Filmmaker

- Lisa Sthalekar, Captain of Australia Women's cricket team

- Mathai Varghese, Mathematician and Professor at the University of Adelaide

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)

- Akshay Venkatesh, Mathematician

- Kaushaliya Vaghela, former Victorian politician, community leader.

- Guy Sebastian, Winner of 2003 Australian Idol, Singer and Songwriter

- Isha Sharvani, Bollywood actress

European–Indian ancestry

- Prue Car, ALP MP for Londonderry in New South Wales

- Christabel Chamarette, Senator from Western Australia from 1992 to 1996

- Stuart Clark, Australian Cricketer

- Chris Crewther, former Liberal MP for Dunkley

- Samantha Downie, Australia's Next Top Model Contestant, Model

- Jeremy Fernandez, ABC weekend presenter and reporter

- Lisa Haydon, Bollywood Actress

- Samantha Jade, Singer, Songwriter and Actress

- Sam Kerr, Footballer

- Daniel Kerr, Australian rules footballer

- Roger Kerr, Australian rules footballer

- Jordan McMahon, Australian rules footballer

- Lauren Moss, ALP MP for Casuarina in the Northern Territory

- Clancee Pearce, Australian Rules Footballer for Fremantle Football Club

- Eric Pearce, former Hockey Player who represented Australia in 4 Olympics

- Julian Pearce, former Hockey Player who represented Australia in 45 international matches

- Rex Sellers, Cricketer and Leg Spinner who played for Australia in India in 1964

- Dave Sharma, former Liberal MP for Wentworth

- Lisa Singh, former ALP Senator representing Tasmania

- Terry Walsh, Australian Hockey Player and Coach

- Anne Warner, former Minister for Aboriginal and Islander Affairs, Queensland Labor Government

- Rhys Williams, Professional footballer

See also

- Australia–India relations

- Fijian-Indian Australians

- Non-resident Indian and person of Indian origin

- Pakistani Australians

- Bangladeshi Australians

- Punjabi Australians

- Australian Sikh Heritage Trail

- Man Mohan Singh (pilot)

- Romani people in Australia

References

- ^ a b c d "General Community Profile" (XLS). 2021 Census of Population and Housing. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "2016 Census Community Profiles: Australia". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (28 April 2020). "Main Features - Australia's Population by Country of Birth". www.abs.gov.au.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Indian population in Australia increases 30 per cent in less than two years; now the third largest migrant group in Australia, SBS, 2 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Hindi is the top Indian language spoken in Australia, SBS, 26 October 2018.

- ^ Migration program report for 2017–18

- ^ a b "Indians found to be Australia's most highly educated migrants - Interstaff Migration". 19 August 2016.

- ^ The story of the Indian diaspora in Australia and New Zealand is 250 years old, qz.com, 30 October 2018.

- ^ Creagh, Sunanda (15 January 2013). "Study links ancient Indian visitors to Australia's first dingoes". The Conversation. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- PMID 23319617.,pp. 1803–1808.

- ^ "An Antipodean Raj". The Economist. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- )

- ^ MacDonald, Anna (15 January 2013). "Research shows ancient Indian migration to Australia". ABC News.

- ISBN 0-19-550457-7.

- ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 24 May 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Klaassen, Nic. "Nuyts, Pieter (1598–1655)". Nuyts, Pieter. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "INTERESTING HISTORICAL NOTES". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 9 October 1923. p. 5. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Howard T. Fry, Alexander Dalrymple (1737–1808) and the Expansion of British Trade, London, Cass for the Royal Commonwealth Society, 1970, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Andrew Cook, Introduction to An account of the discoveries made in the South Pacifick Ocean / by Alexander Dalrymple ; first printed in 1767, reissued with a foreword by Kevin Fewster and an essay by Andrew Cook, Potts Point (NSW), Hordern House Rare Books for the Australian National Maritime Museum, 1996, pp. 38–9.

- ^ The St. James's Chronicle, 11 June and The Public Advertiser, 13 June 1768.

- ^ Historical Records of Australia, Series III, Vol. V, 1922, pp. 743–47, 770.

- ^ a b c d "Indian hawkers". museumvictoria.com.au. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0908120697.

- ^ a b "1788". Objects through Time. NSW Migration Heritage Centre. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ ISBN 9780868408491. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0207154270.

- ^ "An introduction to HINDUISM in Australia | Fact sheet". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Binney, Keith R., Horsemen of the First Frontier (1788-1900) and The Serpents Legacy.

- ^ British East India Company in early Australia, tbheritage.com, accessed 11th February 2024.

- ^ "Convicts and the British colonies in Australia". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007.

- ^ a b "NRS 1155: Musters and other papers relating to convict ships". State Archives of NSW. 11 January 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Phipps (1840), John Phipps (of the Master Attendant's Office, Calcutta) (1840) A Collection of Papers Relative to Ship Building in India ...: Also a Register Comprehending All the Ships ... Built in India to the Present Time .... (Scott). (Google eBook), p. 117 and 180.

- ^ British Library: Almorah.

- ^ "Indian overseas Population - Indians in Australia. Non-resident Indian and Person of Indian Origin". NRIOL.

- ^ "Hinduism / Hinduism by country / Hinduism in australia". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Early Sikhs in Australia, SikhChic.com.

- ^ "Changing Face of early Australia". Australia.gov.au. 13 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b australia.gov.au > About Australia > Australian Stories > Afghan cameleers in Australia Archived 5 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ^ ISBN 9781921536205.

- ^ ISBN 9780521807890.

- ^ "Indiaoz Indian Arts & Literature - Indian Immigration & Australia". www.indiaoz.com.au. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007.

- ^ "Australia immigration - More Immigration from India". workpermit.com. 21 January 2005. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Alan Fenna, "Putting the 'Australian Settlement' in Perspective", Labour History 102 (2012)

- ^ Bruce Smith (Free Trade Party) Parliamentary Debates cited in D.M. Gibb (1973) The Making of White Australia. p. 113. Victorian Historical Association. ISBN

- ^ ISBN 0-14-016638-6., pp.188, 516–517.

- ISBN 0-19-553227-9., pp 67–68.

- ISBN 0-19-555541-4., pp. 5–8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0., p. 93.

- ISSN 0729-6274.

- ISBN 0-642-99375-0.. p. 369.

- ^ "The Far East". Australia's War 1939–1945. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Australasia rising: who we are becoming, The Sydney Morning herald, 2 January 2019.

- ^ "We're not Asia's 'white trash' but we must be careful", The Australian, 10 September 2019.

- Indian Express. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Lauren Wilson (21 January 2010). "Simon Overland admits Indians are targeted in attacks". The Australian. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Sushi Das (13 February 2010). "The politics of violence". The Age, Melbourne. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Race horror: Assailants walk free". Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ PM 'appalled' at attacks on Indian students in Australia Hindustan Times, 9 June 2009.

- ^ Thousands rally against racism in Melbourne – Times of India

- Sydney Morning Herald. Archivedfrom the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "Indians in Australia say Lebanese youths behind attacks". The Times of India. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)" (XLS). Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing: Cultural diversity data summary, 2021" (XLS). Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.skynews.com.au. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Indians in Australia historic population trend, https://www.abs.gov.au, 2012.

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (28 June 2017). "Main Features - Cultural Diversity Article". www.abs.gov.au.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Census reveals rise of Indians in Australia | Indian Herald". Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Cultural diversity of Australia". Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "Australian Bureau of Statistics : 2021 Census of Population and Housing : General Community Profile" (XLSX). Abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Religious affiliation in Australia | Australian Bureau of Statistics". 7 April 2022.

- ^ "India has 79.8% Hindus, 14.2% Muslims, says 2011 census data on religion". Firstpost. 26 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "India-born Community Information Summary" (PDF). 2016.

- ^ Indians and the Antipodes: Networks, Boundaries, and Circulation.

External links

- Indian Magazine and Newspaper in Australia

- Indians Living in Australia

- Indian Communities in Australia

- ^ According to the local classification, South Caucasian peoples (Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Georgians) belong not to the European but to the "Central Asian" group, despite the fact that the territory of Transcaucasia has nothing to do with Central Asia and geographically belongs mostly to Western Asia.