Greater India

| Greater India | |

|---|---|

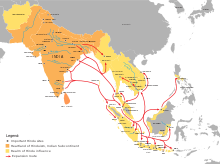

Indian cultural extent Dark orange: The Indian subcontinent[1] Light orange: Southeast Asia culturally linked to India (except Northern Vietnam, Philippines and Western New Guinea) Yellow: Regions with significant Indian cultural influence, notably the Versions of Ramayana) | |

Greater India, also known as the Indian cultural sphere, or the Indic world, is an area composed of many countries and regions in South, East Asia and Southeast Asia that were historically influenced by Indian culture, which itself formed from the various distinct indigenous cultures of these regions.[4] The term Greater India, as a reference to the Indian cultural sphere, was popularised by a network of Bengali scholars in the 1920s. It is an umbrella term encompassing the Indian subcontinent and surrounding countries, which are culturally linked through a diverse cultural cline. These countries have been transformed to varying degrees by the acceptance and introduction of cultural and institutional elements from each other. Since around 500 BCE, Asia's expanding land and maritime trade had resulted in prolonged socio-economic and cultural stimulation and diffusion of Buddhist and Hindu beliefs into the region's cosmology, in particular in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka.[5] In Central Asia, the transmission of ideas was predominantly of a religious nature.

By the early centuries of the

To the north, Indian religious ideas were assimilated into the cosmology of Himalayan peoples, most profoundly in Tibet and Bhutan, and merged with indigenous traditions. Buddhist

Evolution of the concept

The concept of the Three Indias was in common circulation in pre-industrial Europe. Greater India was the southern part of South Asia, Lesser India was the northern part of South Asia, and Middle India was the region near the Middle East.[12] The Portuguese form (Portuguese: India Maior[12][13][14][15]) was used at least since the mid-15th century.[13] The term, which seems to have been used with variable precision,[16] sometimes meant only the Indian subcontinent;[17] Europeans used a variety of terms related to South Asia to designate the South Asian peninsula, including High India, Greater India, Exterior India and India aquosa.[18]

However, in some accounts of European nautical voyages, Greater India (or India Major) extended from the Malabar Coast (present-day Kerala) to India extra Gangem[19] (lit. "India, beyond the Ganges," but usually the East Indies, i.e. present-day Malay Archipelago) and India Minor, from Malabar to Sind.[20] Farther India was sometimes used to cover all of modern Southeast Asia.[18] Until the fourteenth century, India could also mean areas along the Red Sea, including Somalia, South Arabia, and Ethiopia (e.g., Diodorus of Sicily of the first century BC says that "the Nile rises in India" and Marco Polo of the fourteenth century says that "Lesser India ... contains ... Abash [Abyssinia]").[21]

In late 19th-century geography, Greater India referred to a region that included: "(a) Himalaya, (b) Punjab, (c) Hindustan, (d) Burma, (e) Indo-China, (f) Sunda Islands, (g) Borneo, (h) Celebes, and (i) Philippines."[22] German atlases distinguished Vorder-Indien (Anterior India) as the South Asian peninsula and Hinter-Indien as Southeast Asia.[18]

Greater India, or Greater India Basin also signifies "the

The concept of "Indianized kingdoms" and "Indianization", coined by

Indianization of South East Asia

The earliest Hindu kingdoms emerged in Sumatra and Java, followed by mainland polities such as Funan and Champa. Adoption of Indian civilization elements and individual adaptation stimulated the emergence of centralized states and localized caste systems in Southeast Asia.[32][33][34]

Adaption and adoption

Indian culture was likely introduced by Hindu and Buddhist traders, priests, and princes traveled to Southeast Asia from India in the first few centuries of the Common Era and eventually settled there. Strong impulse most certainly came from the region's ruling classes who invited Brahmans to serve at their courts as priests, astrologers and advisers.[35] Divinity and royalty were closely connected in these polities as Hindu rituals validated the powers of the monarch. Brahmans and priests from India proper played a key role in supporting ruling dynasties through exact rituals. Dynastic consolidation was the basis for more centralized kingdoms that emerged in Java, Sumatra, Cambodia, Burma, and along the central and south coasts of Vietnam from the 4th to 8th centuries.[36]

Art, architecture, rituals, and cultural elements such as the

States such as

Southeast Asia is called Suvarnabhumi or Sovannah Phoum – the golden land and Suvarnadvipa – the golden Islands in Sanskrit.[41] It was frequented by traders from eastern India, particularly Kalinga. Cultural and trading relations between the powerful Chola dynasty of South India and the Southeast Asian Hindu kingdoms led the Bay of Bengal to be called "The Chola Lake", and the Chola attacks on Srivijaya in the 10th century CE are the sole example of military attacks by Indian rulers against Southeast Asia. The Pala dynasty of Bengal, which controlled the heartland of Buddhist India, maintained close economic, cultural and religious ties, particularly with Srivijaya.[42]

Religion, authority and legitimacy

The pre-Indic political and social systems in Southeast Asia were marked by a relative indifference towards lineage descent. Hindu God kingship enabled rulers to supersede loyalties, forge cosmopolitan polities and the worship of Shiva and Vishnu was combined with ancestor worship, so that Khmer, Javanese, and Cham rulers claimed semi-divine status as descendants of a God. Hindu traditions, especially the relationship to the sacrality of the land and social structures, are inherent in Hinduism's transnational features. The epic traditions of the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa further legitimized a ruler identified with a God who battled and defeated the wrong doers that threaten the ethical order of the world.[43]

Hinduism does not have a single historical founder, a centralized imperial authority in India proper nor a bureaucratic structure, thus ensuring relative religious independence for the individual ruler. It also allows for multiple forms of divinity, centered upon the Trimurti the triad of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, the deities responsible for the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe.[44]

The effects of Hinduism and Buddhism applied a tremendous impact on the many civilizations inhabiting Southeast Asia which significantly provided some structure to the composition of written traditions. An essential factor for the spread and adaptation of these religions originated from trading systems of the third and fourth century.[45] In order to spread the message of these religions Buddhist monks and Hindu priests joined mercantile classes in the quest to share their religious and cultural values and beliefs. Along the Mekong delta, evidence of Indianized religious models can be observed in communities labeled Funan. There can be found the earliest records engraved on a rock in Vocanh.[46] The engravings consist of Buddhist archives and a south Indian scripts are written in Sanskrit that have been dated to belong to the early half of the third century. Indian religion was profoundly absorbed by local cultures that formed their own distinctive variations of these structures in order to reflect their own ideals.

The indianized kingdoms had by the 1st to 4th centuries CE adopted Hinduism's cosmology and rituals, the devaraja concept of kingship, and Sanskrit as official writing. Despite the fundamental cultural integration, these kingdoms were autonomous in their own right and functioned independently.[47]

Waning of Indianization

Khmer Kingdom

Not only did Indianization change many cultural and political aspects, but it also changed the spiritual realm as well, creating a type of Northern Culture which began in the early 14th century, prevalent for its rapid decline in the Indian kingdoms. The decline of Hinduism kingdoms and spark of Buddhist kingdoms led to the formation of orthodox Sinhalese Buddhism and is a key factor leading to the decline of Indianization. Sukhothai and Ceylon are the prominent characters who formulated the center of Buddhism and thus became more popularized over Hinduism.[48]

Rise of Islam

Not only was the spark of Buddhism the driving force for Indianization coming to an end, but Islamic control took over as well in the midst of the thirteenth century to trump the Hinduist kingdoms. In the process of Islam coming to the traditional Hinduism kingdoms, trade was heavily practiced and the now Islamic Indians started becoming merchants all over Southeast Asia.[48] Moreover, as trade became more saturated in the Southeast Asian regions wherein Indianization once persisted, the regions had become more Muslim populated. This so-called Islamic control has spanned to many of the trading centers across the regions of Southeast Asia, including one of the most dominant centers, Malacca, and has therefore stressed a widespread rise of Islamization.[48]

Indianized kingdoms of South East Asia

Mainland kingdoms

- exonym based on the accounts of two Chinese diplomats, Kang Tai and Zhu Ying who sojourned there in the mid-3rd century CE.[49]: 24 It is not known what name the people of Funan gave to their polity. Some scholars believe ancient Chinese scholars transcribed the word Funan from a word related to the Khmer word bnaṃ or vnaṃ (modern: phnoṃ, meaning "mountain"); while others thought that Funan may not be a transcription at all, rather it meant what it says in Chinese, meaning something like "Pacified South". Centered at the lower Mekong,[50] Funan is noted as the oldest Hindu culture in this region, which suggests prolonged socio-economic interaction with India and maritime trading partners of the Indosphere.[7] Cultural and religious ideas had reached Funan via the Indian Ocean trade route. Trade with India had commenced well before 500 BC as Sanskrit had not yet replaced Pali.[7] Funan's language has been determined as to have been an early form of Khmer and its written form was Sanskrit.[51]

- royal chronology ended in the 14th century. During this period of the Khmer empire, societal functions of administration, agriculture, architecture, hydrology, logistics, urban planning, literature and the arts saw an unprecedented degree of development, refinement and accomplishment from the distinct expression of Hindu cosmology.[60]

- Pegu) were notable for facilitating Indianized cultural exchange in lower Burma, in particular by having strong ties with Sri Lanka.[61]

- Sukhothai: The first Tai peoples to gain independence from the Khmer Empire and start their own kingdom in the 13th century. Sukhothai was a precursor for the Ayutthaya Kingdom and the Kingdom of Siam. Though ethnically Thai, the Sukhothai kingdom in many ways was a continuation of the Buddhist Mon-Dvaravati civilizations, as well as the neighboring Khmer Empire.[62][63]

Island kingdoms

- Salakanagara: Salakanagara kingdom is the first historically recorded Indianized kingdom in Western Java, established by an Indian trader after marrying a local Sundanese princess. This Kingdom existed between 130 and 362 CE.[64]

- Tarumanagara was an early Sundanese Indianized kingdom, located not far from modern Jakarta, and according to Tugu inscription ruler Purnavarman apparently built a canal that changed the course of the Cakung River, and drained a coastal area for agriculture and settlement. In his inscriptions, Purnavarman associated himself with Vishnu, and Brahmins ritually secured the hydraulic project.

- Kalingga: Kalingga (Javanese: Karajan Kalingga) was the 6th century Indianized kingdom on the north coast of Central Java, Indonesia. It was the earliest Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Central Java, and together with Kutai and Tarumanagara are the oldest kingdoms in Indonesian history.

- Malayu was a classical Southeast Asian kingdom. The primary sources for much of the information on the kingdom are the New History of the Tang, and the memoirs of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yijing who visited in 671 CE, and states that it was "absorbed" by Srivijaya by 692 CE, but had "broken away" by the end of the eleventh century according to Chao Jukua. The exact location of the kingdom is the subject of studies among historians.

- Nalanda university near Pala territory. The Srivijaya kingdom ceased to exist in the 13th century due to various factors, including the expansion of the Javanese, Singhasari, and Majapahit empires.[65]

- Tambralinga was an ancient kingdom located on the Malay Peninsula that at one time came under the influence of Srivijaya. The name had been forgotten until scholars recognized Tambralinga as Nagara Sri Dharmaraja (Nakhon Si Thammarat). Early records are scarce but its duration is estimated to range from the seventh to the fourteenth century. Tambralinga first sent tribute to the emperor of the Tang dynasty in 616 CE. In Sanskrit, Tambra means "red" and linga means "symbol", typically representing the divine energy of Shiva.

- Isyana Dynasty.

- Kadiri: In the 10th century, Mataram challenged the supremacy of Srivijaya, resulting in the destruction of the Mataram capital by Srivijaya early in the 11th century. Restored by King Airlangga (c. 1020–1050), the kingdom split on his death; the new state of Kediri, in eastern Java, became the centre of Javanese culture for the next two centuries, spreading its influence to the eastern parts of Southeast Asia. The spice trade was now becoming increasingly important, as demand from European countries grew. Before they learned to keep sheep and cattle alive in the winter, they had to eat salted meat, made palatable by the addition of spices. One of the main sources was the Maluku Islands (or "Spice Islands") in Indonesia, and so Kediri became a strong trading nation.

- , the southern Celebes and the Moluccas. It also exerted considerable influence on the mainland.

- Majapahit: The Majapahit empire, centered in East Java, succeeded the Singhasari empire and flourished in the Indonesian archipelago between the 13th and 15th centuries. Noted for their naval expansion, the Javanese spanned west–east from Lamuri in Aceh to Wanin in Papua. Majapahit was one of the last and greatest Hindu empires in Maritime Southeast Asia. Most of Balinese Hindu culture, traditions and civilisations were derived from Majapahit legacy. A large number of Majapahit nobles, priests, and artisans found their home in Bali after the decline of Majapahit to Demak Sultanate.

- Citanduyand Cimanuk rivers, with its territory spanning from Citarum river on the west, to the Pamali (present-day Brebes river) and Serayu rivers on the east. Its capital was located in Kawali, near present-day Ciamis city.

- Sunda: The Kingdom of Sunda was a Hindu kingdom located in western Java from 669 CE to around 1579 CE, covering the area of present-day Banten, Jakarta, West Java, and the western part of Central Java. According to primary historical records, the Bujangga Manik manuscript, the eastern border of the Sunda Kingdom was the Pamali River (Ci Pamali, the present day Brebes River) and the Serayu River (Ci Sarayu) in Central Java.

Indianized kingdoms of South West Asia

The eastern regions of Afghanistan were considered politically as parts of India. Buddhism and Hinduism held sway over the region until the Muslim conquest.

According to historian

Archaeological sites such as the 8th-century

The Caliph

Zabulistan

The

Buddhist Turk Shahi dynasty of Kabul

The area had been under the rule of the

The Turk Shahi were a Buddhist

Hindu Shahi dynasty of Kabul

The Hindu Shahi (850–1026 CE) was a

According to available inscriptions following are the names of Hindu Shahi kings: Vakkadeva, Kamalavarman, Bhimadeva,

- Vakkadeva: According to The Mazare Sharif Inscription of the Time of the Shahi Ruler Veka, recently discovered from northern Afghanistan and reported by the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations, Veka (sic.) conquered northern region of Afghanistan 'with eightfold forces' and ruled there. He established a Shiva temple there which was inaugurated by Parimaha Maitya (the Great Minister).[95] He also issued copper coins of the Elephant and Lion type with the legend Shri Vakkadeva. Nine principal issues of Bull and Horseman silver coins and only one issue of corresponding copper coins of Spalapatideva have become available. As many as five Elephant and Lion type of copper coins of Shri Vakkadeva are available and curiously the copper issues of Vakka are contemporaneous with the silver issues of Spalapati.[88]

- Kamalavarman: During the reign of Kamalavarman, the Saffarid rule weakened precipitately and ultimately Sistan became a part of the Lawik", a Hindu, as the ruler at Ghazni, before this place was taken over by the Turkish slave governor of the Samanids.[96]

- Jayapala: With Jayapala, a new dynasty started ruling over the former Shahi kingdom of southeastern Afghanistan and the change over was smooth and consensual. On his coronation, Jayapala used the additional name-suffix Deva from his predecessor's dynasty in addition to the pala name-ending of his own family. (With Kabul lost during the lifetime of Jayapaladeva, his successors – Anandapala, Trilochanapala and Bhimapala – reverted to their own family pala-ending names.) Jayapala did not issue any coins in his own name. Bull and Horseman coins with the legend Samantadeva, in billon, seem to have been struck during Jayapala's reign. As the successor of Bhima, Jayapala was a Shahi monarch of the state of Kabul, which now included Punjab. Minhaj-ud-din describes Jayapala as "the greatest of the Rais of Hindustan."[90]

Balkh

From historical evidence, it appears

Ghur

Nuristan

The vast area extending from modern

Successive wave of

In 1020–21, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna led a campaign against Kafiristan and the people of the "pleasant valleys of Nur and Qirat" according to Gardizi.

Indian cultural influence

The use of Greater India to refer to an Indian cultural sphere was popularised by a network of Bengali scholars in the 1920s who were all members of the Calcutta-based Greater India Society. The movement's early leaders included the historian R. C. Majumdar (1888–1980); the philologists Suniti Kumar Chatterji (1890–1977) and P. C. Bagchi (1898–1956), and the historians Phanindranath Bose and Kalidas Nag (1891–1966).[114][115] Some of their formulations were inspired by concurrent excavations in Angkor by French archaeologists and by the writings of French Indologist Sylvain Lévi. The scholars of the society postulated a benevolent ancient Indian cultural colonisation of Southeast Asia, in stark contrast – in their view – to the Western colonialism of the early 20th century.[116][117][118]

The term Greater India and the notion of an explicit Hindu expansion of ancient Southeast Asia have been linked to both Indian nationalism[119] and Hindu nationalism.[120] However, many Indian nationalists, like Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore, although receptive to "an idealisation of India as a benign and uncoercive world civiliser and font of global enlightenment,"[121] stayed away from explicit "Greater India" formulations.[122] In addition, some scholars have seen the Hindu/Buddhist acculturation in ancient Southeast Asia as "a single cultural process in which Southeast Asia was the matrix and South Asia the mediatrix."[123] In the field of art history, especially in American writings, the term survived due to the influence of art theorist Ananda Coomaraswamy. Coomaraswamy's view of pan-Indian art history was influenced by the "Calcutta cultural nationalists."[124]

By some accounts Greater India consists of "lands including Burma,

Cultural expansion

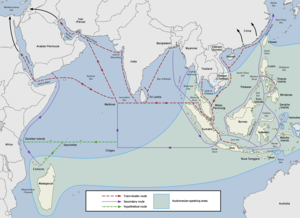

Culture spread via the trade routes that linked India with southern

A defining characteristic of the cultural link between Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent was the adoption of ancient Indian

.Beyond the

Cultural commonalities

Religion, mythology and folklore

- Cham peopleof Vietnam still practice Hinduism as well. Though officially Buddhist, many Thai, Khmer, and Burmese people also worship Hindu gods in a form of syncretism.

- Brahmins have had a large role in spreading Hinduism in Southeast Asia. Even today many monarchies such as the royal court of Thailand still have Hindu rituals performed for the King by Hindu Brahmins.[134][135]

- Thailand and Ulaanbaatar.

- Muay Thai, a fighting art that is the Thai version of the Hindu Musti-yuddha style of martial art.

- Kaharingan, an indigenous religion followed by the Dayak people of Borneo, is categorised as a form of Hinduism in Indonesia.

- Philippine mythology includes the supreme god Bathala and the concept of Diwata and the still-current belief in Karma—all derived from Hindu-Buddhist concepts.

- .

- Wayang shadow puppets and classical dance-dramas of Indonesia, Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand took stories from episodes of Ramayana and Mahabharata.

Caste system

Indians spread their religion to Southeast Asia, beginning the Hindu and Buddhist cultures there. They introduced the

Architecture and monuments

- The same style of Hindu temple architecture was used in several ancient temples in South East Asia including Angkor Wat, which was dedicated to Hindu god Vishnu and is shown on the flag of Cambodia, also Prambanan in Central Java, the largest Hindu temple in Indonesia, is dedicated to Trimurti — Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma.

- Austronesian step pyramid.

- The minarets of 15th- to 16th-century mosques in Indonesia, such as the Great Mosque of Demak and Kudus mosque resemble those of MajapahitHindu temples.

- The Batu Caves in Malaysia are one of the most popular Hindu shrines outside India. It is the focal point of the annual Thaipusam festival in Malaysia and attracts over 1.5 million pilgrims, making it one of the largest religious gatherings in history.[136]

- Brahma, is one of the most popular religious shrines in Thailand.[137]

Sport

It is conjectured that certain

Linguistic influence

Scholars like Sheldon Pollock have used the term Sanskrit Cosmopolis to describe the region and argued for millennium-long cultural exchanges without necessarily involving migration of peoples or colonisation. Pollock's 2006 book The Language of the Gods in the World of Men makes a case for studying the region as comparable with Latin Europe and argues that the Sanskrit language was its unifying element.

Scripts in Sanskrit discovered during the early centuries of the Common Era are the earliest known forms of writing to have extended all the way to Southeast Asia. Its gradual impact ultimately resulted in its widespread domain as a means of dialect which evident in regions, from Bangladesh to Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand and additionally a few of the larger Indonesian islands. In addition, alphabets from languages spoken in Burmese, Thai, Laos, and Cambodia are variations formed off of Indian ideals that have localized the language.

The spread of Buddhism to Tibet allowed many Sanskrit texts to survive only in Tibetan translation (in the

In Southeast Asia, languages such as

Many Sanskrit loanwords are also found in

.A Sanskrit loanword encountered in many Southeast Asian languages is the word bhāṣā, or spoken language, which is used to mean language in general, for example bahasa in Malay, Indonesian and Tausug, basa in Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese, phasa in Thai and Lao, bhasa in Burmese, and phiesa in Khmer.

Literature

Scripts in Sanskrit discovered during the early centuries of the Common Era are the earliest known forms of writing to have extended all the way to Southeast Asia. Its gradual impact ultimately resulted in its widespread domain as a means of dialect which evident in regions, from Bangladesh to Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand and additionally a few of the larger Indonesian islands. In addition, alphabets from languages spoken in Burmese, Thai, Laos, and Cambodia are variations formed off of Indian ideals that have localized the language.[45]

The utilization of Sanskrit has been prevalent in all aspects of life including legal purposes. Sanskrit terminology and vernacular appears in ancient courts to establish procedures that have been structured by Indian models such as a system composed of a code of laws. The concept of legislation demonstrated through codes of law and organizations particularly the idea of "God King" was embraced by numerous rulers of Southeast Asia.[48] The rulers amid this time, for example, the Lin-I Dynasty of Vietnam once embraced the Sanskrit dialect and devoted sanctuaries to the Indian divinity, Shiva. Many rulers following even viewed themselves as "reincarnations or descendants" of the Hindu Gods. However, once Buddhism began entering the nations, this practiced view was eventually altered.

Linguistic commonalities

- In the Visayan[143] contain numerous Sanskrit loanwords.

- In Mainland Southeast Asia: Thai, Lao, Burmese, and Khmer language have absorbed a significant amount of Sanskrit as well as Pali words.

- Many Indonesian names have Sanskrit origin (e.g. Dewi Sartika, Megawati Sukarnoputri, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Teuku Wisnu).

- Southeast Asian languages are traditionally written with Indic alphabets and therefore have extra letters not pronounced in the local language, so that original Sanskrit spelling can be preserved. An example is how the name of the late King of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, is spelled in Sanskrit as "Bhumibol"ภูมิพล, yet is pronounced in Thai as "Phumipon" พูมิพน using Thai-Sanskrit pronunciation rules since the original Sanskrit sounds do not exist in Thai. [144]

Toponyms

- Suvarnabhumi is a toponym that has been historically associated with Southeast Asia. In Sanskrit, it means "The Land of Gold". Thailand's Suvarnabhumi Airport is named after this toponym.

- Several of Indonesian .

- Siamese ancient city of Ayutthayaalso derived from Ramayana's Ayodhya.

- Names of places could simply render their Sanskrit origin, such as Singapore, from Singapura (Singha-pura the "lion city"), Jakarta from Jaya and kreta ("complete victory").

- Some of the Indonesian regencies such as Indragiri Hulu and Indragiri Hilir derived from Indragiri River, Indragiri itself means "mountain of Indra".

- Some Thai toponyms also often have Indian parallels or Sanskrit origin, although the spellings are adapted to the Siamese tongue, such as Ratchaburi from Raja-puri ("king's city"), and Nakhon Si Thammarat from Nagara Sri Dharmaraja.

- The tendency to use Sanskrit for modern neologism also continued to modern day. In 1962 Indonesia changed the colonial name of New Guinean city of Hollandia to Jayapura ("glorious city"), Orange mountain range to Jayawijaya Mountains.

- Malaysia named their new government seat as Putrajaya ("prince of glory") in 1999.

See also

- South Asian diaspora

- Global Southeast, a significantly coterminous region

- Indus–Mesopotamia relations

- Indo-Roman trade relations

- Sanskrit-related topics

Citations

- JSTOR 26534911.

It is important to note that Nepal was not a British colony like India. Geographically, culturally, socially and historically India and Nepal are linked most intimately and lived together from time immemorial. The most significant factor which has nurtured Indo-Nepalese relations through ages is geographical setting of the two countries which is a good example to understand that how geography connects the two countries.

- OCLC 557595150.

Modern Afghanistan was part of ancient India; the Afghans belonged to the pale of Indo-Aryan civilisation. In the eighty century, the country was known by two regional names—Kabul land Zabul. The northern part, called Kabul (or Kabulistan) was governed by a Buddhist dynasty. Its capital and the river on the banks of which it was situated, also bore the same name. Lalliya, a Brahmin minister of the last Buddhist ruler Lagaturman, deposed his master and laid the foundation of the Hindushahi dynasty in c. 865.

- ISBN 9788124110669.

Although Afghanistan was considered an integral part of India in antiquity, and was often called "Little India" even in medieval times, politically it had not been a part of India after the downfall of the Kushan empire, followed by the defeat of the Hindu Shahis by Mahmud Ghazni.

- ISBN 978-81-206-0772-9. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-0843-3. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ from the original on 12 August 2021, retrieved 23 December 2015

- ^ a b c Stark, Miriam T.; Griffin, Bion; Phoeurn, Chuch; Ledgerwood, Judy; et al. (1999). "Results of the 1995–1996 Archaeological Field Investigations at Angkor Borei, Cambodia" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 38 (1). University of Hawai'i-Manoa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

The development of maritime commerce and Hindu influence stimulated early state formation in polities along the coasts of mainland Southeast Asia, where passive indigenous populations embraced notions of statecraft and ideology introduced by outsiders...

- ^ Coedès (1968), pp. 14–.

- ^ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2002), "From Funan to Sriwijaya: Cultural continuities and discontinuities in the Early Historical maritime states of Southeast Asia", 25 tahun kerjasama Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi dan Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi / EFEO, pp. 59–82, archived from the original on 26 March 2023, retrieved 26 March 2023

- ^ "Buddhism in China: A Historical Overview" (PDF). The Saylor Foundation 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Zhu, Qingzhi (March 1995). "Some Linguistic Evidence for Early Cultural Exchange between China and India" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 66. University of Pennsylvania. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

everyone knows well the so-called "Buddhist conquest of China" or "Indianized China"

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-820740-5.

- ^ a b (Azurara 1446)

- ISBN 978-0-520-20742-4.

- ^ Pedro Machado, José (1992). "Terras de Além: no Relato da Viagem de Vasco da Gama". Journal of the University of Coimbra. 37: 333–.

- ^ (Beazley 1910, p. 708) Quote: "Azurara's hyperbole, indeed, which celebrates the Navigator Prince as joining Orient and Occident by continual voyaging, as transporting to the extremities of the East the creations of Western industry, does not scruple to picture the people of the Greater and the Lesser India"

- ^ (Beazley 1910, p. 708) Quote: "Among all the confusion of the various Indies in Mediaeval nomenclature, "Greater India" can usually be recognized as restricted to the "India proper" of the modern [c. 1910] world."

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-20742-4.

- ^ (Wheatley 1982, p. 13) Quote: "Subsequently the whole area came to be identified with one of the "Three Indies," though whether India Major or Minor, Greater or Lesser, Superior or Inferior, seems often to have been a personal preference of the author concerned. When Europeans began to penetrate into Southeast Asia in earnest, they continued this tradition, attaching to various of the constituent territories such labels as Further India or Hinterindien, the East Indies, the Indian Archipelago, Insulinde, and, in acknowledgment of the presence of a competing culture, Indochina."

- ^ (Caverhill 1767)

- ISBN 978-3-447-05607-6.

- ^ "Review: New Maps," (1912) Bulletin of the American Geographical Society 44(3): 235–240.

- ^ (Ali & Aitchison 2005, p. 170)

- ^ Argand, E., 1924. La tectonique de l' Asie. Proc. 13th Int. Geol. Cong. 7 (1924), 171–372.

- ^ "The Greater India Basin hypothesis" (PDF). University of Oslo. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ National Library of Australia. Asia's French Connection : George Coedes and the Coedes Collection Archived 21 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- .

- ^ ISBN 9783319338224. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9781588395245.

- ISBN 978-0415100540.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9781285783086. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-Central Thailand". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ^ "Southeast Asia: Imagining the region" (PDF). Amitav Acharya. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "The spread of Hinduism in Southeast Asia and the Pacific". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Chenla – 550–800". Global Security. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Hinduism in Southeast Asia". Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Coedes, George (1964). Some Problems in Ancient History of the Hinduized States of South-East Asia. Journal of Southeast Asian History.

- ^ Theories of Indianisation Archived 24 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Exemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia), by Dr. Helmut Lukas

- ^ Helmut Lukas. "THEORIES OF INDIANIZATION Exemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia)" (PDF). Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ISBN 9788120749108. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Takashi Suzuki (25 December 2012). "Śrīvijaya―towards ChaiyaーThe History of Srivijaya". Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Hinduism in Southeast Asia". Oxford Press. 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ISBN 978-81-269-0775-5. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ JSTOR 3632296.

- ^ Kleinmeyer, Cindy. "Religions of Southeast Asia" (PDF). niu.edu. Northern Illinois University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Parker, Vrndavan Brannon. "Vietnam's Champa Kingdom Marches on". Hinduism Today. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Coedes (1967)

- ISBN 9781842125847

- ^ Stark, Miriam T. (2006). "Pre-Angkorian Settlement Trends in Cambodia's Mekong Delta and the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project" (PDF). Indo-Pacific Pre-History Association Bulletin. 26. University of Hawai'i-Manoa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

The Mekong delta played a central role in the development of Cambodia's earliest complex polities from approximately 500 BC to AD 600.

- ^ Rooney, Dawn (1984). Khmer Ceramics (PDF). Oxford University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

The language of Funan was...

- ^ Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture by Upendra Thakur p.2

- ^ "Considerations on the Chronology and History of 9th Century Cambodia by Dr. Karl-Heinz Golzio, Epigraphist – ...the realm called Zhenla by the Chinese. Their contents are not uniform but they do not contradict each other" (PDF). Khmer Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ISBN 9789004119734. Archivedfrom the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9780522854770. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "The Cham: Descendants of Ancient Rulers of South China Sea Watch Maritime Dispute From Sidelines Written by Adam Bray". IOC-Champa. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ISBN 9780521243339. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- S2CID 161969465.

- ^ "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire – Many scholars attribute the halt of the development of Angkor to the rise of Theravada..." (PDF). Studies of Asia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Khmer Empire". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Coedès (1968)

- ^ a b sunnytantikumar736. "भारत की कहानी". Hindi Stories. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ พระราชพงษาวดาร ฉบับพระราชหัดถเลขา ภาค 1 [Royal Chronicle: Royal Autograph Version, Volume 1]. Bangkok: Wachirayan Royal Library. 1912. p. 278.

- ^ "Salakanagara, Kerajaan "Tertua" di Nusantara" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Thailand's World : The Srivijaya Kingdom in Thailand". Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar(1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Age of Imperial Unity. G. Allen & Unwin. p. 635.

- ISBN 9780520294134. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 0391041738.

- ^ ISBN 0391041738

- ^ "15. The Rutbils of Zabulistan and the "Emperor of Rome" | Digitaler Ausstellungskatalog". pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ISBN 9783895003646.

- ISBN 1-886439-02-8

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. Readings in Political History of India, Ancient, Mediaeval, and Modern. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 223.

- ISBN 9789231032110. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9780521200936. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-415-29826-1. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9781844670208. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-317-14002-3.

Ibn Battuta, the renowned Moroccan fourteenth century world traveller remarked in a spine-chilling passage that Hindu Kush means slayer of the Indians, because the slave boys and girls who are brought from India die there in large numbers as a result of the extreme cold and the quantity of snow.

- ISBN 978-0-906094-03-7

- ^ John Leyden, Esq.; William Erskine, Esq., eds. (1921). "Events Of The Year 910 (1525)". Memoirs of Babur. Packard Humanities Institute. p. 8. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Abdur Rahman, Last Two Dynasties of the Shahis: "In about AD 680, the Rutbil was a brother of the Kabul Shahi. In AD 726, the ruler of Zabulistan (Rutbil) was the nephew of Kabul Shah. Obviously the Kabul Shahs and the Rutbils belonged to the same family" – pp. 46 and 79, quoting Tabri, I, 2705-6 and Fuch, von W.

- ^ "The Temple of Zoor or Zoon in Zamindawar". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1977). The Medieval History of Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. Variorum Reprints. p. 344.

- ISBN 9004095098.

- ISBN 9781317340911. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 0391041738.

- ^ "15. The Rutbils of Zabulistan and the "Emperor of Rome"". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ a b c D. W. Macdowall, "The Shahis of Kabul and Gandhara" Numismatic Chronicle, Seventh Series, Vol. III, 1968, pp. 189–224, see extracts in R. T. Mohan, AFGHANISTAN REVISITED … Appendix –B, pp. 164–68

- ^ a b Raizada Harichand Vaid, Gulshane Mohyali, II, pp. 83 and 183-84.

- ^ H. G. Raverty, Tr. Tabaqat-i-Nasiri of Maulana Minhaj-ud-din, Vol. I, p. 82

- ^ "16. The Hindu Shahis in Kabulistan and Gandhara and the Arab conquest". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ISBN 9789693514131. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87586-860-8. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Yogendra Mishara, The Hindu Shahis of Afghanistan and the Punjab AD 865-1026, p. 4.

- ^ See R. T. Mohan, AFGHANISTAN REVISITED … Appendix – A, pp. 162–163.

- ^ C. E. Bosworth, 'Notes on Pre-Ghaznavid History of Eastern Afghanistan, Islamic Quarterly, Vol. XI, 1965.

- ISBN 9780754669562.

- ISBN 9780754669562. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9781446545638. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9780520294134. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9780199687053. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Medieval India Part 1 Satish Chandra Page 22

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia, C.E. Bosworth, M.S. Asimov, p. 184.

- ISBN 9788124110645. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ a b Alberto M. Cacopardo (2016). "Fence of Peristan – The Islamization of the "Kafirs" and Their Domestication". Archivio per l'Antropologia e la Etnologia. Società Italiana di Antropologia e Etnologia: 69, 77. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ISBN 9780700706297. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Richard F. Strand (31 December 2005). "Richard Strand's Nuristân Site: Peoples and Languages of Nuristan". nuristan.info. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- H. A. R. Gibb; J. H. Kramers; E. Lévi-Provençal; J. Schact; Bernard Lewis; Charles Pellat, eds. (1986). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: New Edition – Volume I. Brill. p. 852.

- ISBN 9780520294134. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Ram Sharan Sharma. A Comprehensive History of India. Orient Longmans. p. 357.

- ISBN 9781107456594. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Mohammad Habib. Politics and Society During the Early Medieval Period: Collected Works of Professor Mohammad Habib, Volume 2. People's Publishing House. pp. 58–59, 100.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar(1966). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The struggle for empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 13.

- ^ Bayley (2004, p. 710)

- ^ Gopal, Ram; Paliwal, KV (2005). Hindu Renaissance: Ways and Means. New Delhi, India: Hindu Writers Forum. p. 83.

We may conclude with a broad survey of the Indian colonies in the Far East. For nearly fifteen hundred years, and down to a period when the Hindus had lost their independence in their own home, Hindu kings were ruling over Indo-China and the numerous islands of the Indian Archipelago, from Sumatra to New Guinea. Indian religion, Indian culture, Indian laws, and Indian government moulded the lives of the primitive races all over this wide region, and they imbibed a more elevated moral spirit and a higher intellectual taste through the religion, art, and literature of India. In short, the people were lifted to a higher plane of civilisation.

- ^ Bayley (2004, p. 712)

- ^ Review by 'SKV' of The Hindu Colony of Cambodia by Phanindranath Bose [Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House 1927] in The Vedic Magazine and Gurukula Samachar 26: 1927, pp. 620–1.

- ISBN 9782503524474Quote: "The ancient Hindus of yore were not simply a spiritual people, always busy with mystical problems and never trouble themselves with the questions of 'this world'... India also has its Napoleons and Charlemagnes, its Bismarcks and Machiavellis. But the real charm of Indian history does not consist in these aspirants after universal power, but in its peaceful and benevolent Imperialism – a unique thing in the history of mankind. The colonisers of India did not go with sword and fire in their hands; they used... the weapons of their superior culture and religion... The Buddhist age has attracted special attention, and the French savants have taken much pains to investigate the splendid monuments of the Indian cultural empire in the Far East."

- ^ Keenleyside (1982, pp. 213–214) Quote: "Starting in the 1920s under the leadership of Kalidas Nag – and continuing even after independence – a number of Indian scholars wrote extensively and rapturously about the ancient Hindu cultural expansion into and colonisation of South and Southeast Asia. They called this vast region "Greater India" – a dubious appellation for a region which to a limited degree, but with little permanence, had been influenced by Indian religion, art, architecture, literature and administrative customs. As a consequence of this renewed and extensive interest in Greater India, many Indians came to believe that the entire South and Southeast Asian region formed the cultural progeny of India; now that the sub-continent was reawakening, they felt, India would once again assert its non-political ascendancy over the area... While the idea of reviving the ancient Greater India was never officially endorsed by the Indian National Congress, it enjoyed considerable popularity in nationalist Indian circles. Indeed, Congress leaders made occasional references to Greater India while the organisation's abiding interest in the problems of overseas Indians lent indirect support to the Indian hope of restoring the alleged cultural and spiritual unity of South and Southeast Asia."

- ^ Thapar (1968, pp. 326–330) Quote: "At another level, it was believed that the dynamics of many Asian cultures, particularly those of Southeast Asia, arose from Hindu culture, and the theory of Greater India derived sustenance from Pan-Hinduism. A curious pride was taken in the supposed imperialist past of India, as expressed in sentiments such as these: "The art of Java and Kambuja was no doubt derived from India and fostered by the Indian rulers of these colonies." (Majumdar, R. C. et al. (1950), An Advanced History of India, London: Macmillan, p. 221) This form of historical interpretation, which can perhaps best be described as being inspired by Hindu nationalism, remains an influential school of thinking in present historical writings."

- ^ Bayley (2004, pp. 735–736) Quote:"The Greater India visions which Calcutta thinkers derived from French and other sources are still known to educated anglophone Indians, especially but not exclusively Bengalis from the generation brought up in the traditions of post-Independence Nehruvian secular nationalism. One key source of this knowledge is a warm tribute paid to Sylvain Lévi and his ideas of an expansive, civilising India by Jawaharlal Nehru himself, in his celebrated book, The Discovery of India, which was written during one of Nehru's periods of imprisonment by the British authorities, first published in 1946, and reprinted many times since.... The ideas of both Lévi and the Greater India scholars were known to Nehru through his close intellectual links with Tagore. Thus Lévi's notion of ancient Indian voyagers leaving their invisible 'imprints' throughout east and southeast Asia was for Nehru a recapitulation of Tagore's vision of nationhood, that is an idealisation of India as a benign and uncoercive world civiliser and font of global enlightenment. This was clearly a perspective which defined the Greater India phenomenon as a process of religious and spiritual tutelage, but it was not a Hindu supremacist idea of India's mission to the lands of the Trans-Gangetic Sarvabhumi or Bharat Varsha."

- ^ Narasimhaiah (1986) Quote: "To him (Nehru), the so-called practical approach meant, in practice, shameless expediency, and so he would say, "the sooner we are not practical, the better". He rebuked a Member of Indian Parliament who sought to revive the concept of Greater India by saying that 'the honorable Member lived in the days of Bismarck; Bismarck is dead, and his politics more dead!' He would consistently plead for an idealistic approach and such power as the language wields is the creation of idealism—politics' arch enemy—which, however, liberates the leader of a national movement from narrow nationalism, thus igniting in the process a dead fact of history, in the sneer, "For him the Bastille has not fallen!" Though Nehru was not to the language born, his utterances show a remarkable capacity for introspection and sense of moral responsibility in commenting on political processes."

- Sylvain Leviwas perhaps overenthusiastic when he claimed that India produced her definitive masterpieces – he was thinking of Angkor and the Borobudur – through the efforts of foreigners or on foreign soil. Those masterpieces were not strictly Indian achievements: rather were they the outcome of a Eutychian fusion of natures so melded together as to constitute a single cultural process in which Southeast Asia was the matrix and South Asia the mediatrix."

- ^ Guha-Thakurta (1992, pp. 159–167)

- ^ a b c (Bayley 2004, p. 713)

- ^ Handy (1930, p. 364) Quote: "An equally significant movement is one that brought about among the Indian intelligentsia of Calcutta a few years ago the formation of what is known as the "Greater India Society," whose membership is open "to all serious students of the Indian cultural expansion and to all sympathizers of such studies and activities." Though still in its infancy, this organisation has already a large membership, due perhaps as much as anything else to the enthusiasm of its Secretary and Convener, Dr. Kalidas Nag, whose scholarly affiliations with the Orientalists in the University of Paris and studies in Indochina, Insulindia and beyond, have equipped him in an unusual way for the work he has chosen, namely stimulating interest in and spreading knowledge of Greater Indian culture of the past, present and future. The Society's President is Professor Jadunath Sarkar, Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University, and its Council is made up largely of professors on the faculty of the University and members of the staff of the Calcutta Museum, as well as of Indian authors and journalists. Its activities have included illustrated lecture series at the various universities throughout India by Dr. Nag, the assembling of a research library, and the publication of monographs of which four very excellent examples have already been printed: 1) Greater India, by Kalidas Nag, M.A., D.Litt. (Paris), 2) India and China, by Prabodh Chandra Bagchi, M.A., D.Litt., 3) Indian Culture in Java and Sumatra, by Bijan Raj Chatterjee, D.Litt. (Punjab), PhD (London), and 4) India and Central Asia, by Niranjan Prasad Chakravarti, M.A., PhD(Cantab.)."

- ^ Majumdar (1960, pp. 222–223)

- ^ Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson (1911), From Constantinople to the home of Omar Khayyam: travels in Transcaucasia and northern Persia for historic and literary research, The Macmillan company, archived from the original on 26 March 2023, retrieved 15 December 2015,

... they are now wholly substantiated by the other inscriptions.... They are all Indian, with the exception of one written in Persian... dated in the same year as the Hindu tablet over it... if actual Gabrs (i.e. Zoroastrians, or Parsis) were among the number of worshipers at the shrine, they must have kept in the background, crowded out by Hindus, because the typical features Hanway mentions are distinctly Indian, not Zoroastrian... met two Hindu Fakirs who announced themselves as 'on a pilgrimage to this Baku Jawala Ji'....

- ISBN 978-0-86442-425-9,

... The Hindu calendar (Vikramaditya) is 57 years ahead of the Christian calendar. Dates in the Hindu calendar are prefixed by the word: samvat संवत ...

- ISBN 0-19-925591-1

- ^ from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Balinese Religion Archived 10 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McGovern, Nathan (2010). "Sacred Texts, Ritual Traditions, Arts, Concepts: "Thailand"". In Jacobsen, Knut A. (ed.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism (Volume 2 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 371–378.

- from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ "Batu Caves Inside and Out, Malaysia". lonelyplanet.tv. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008.

- ^ Buddhist Channel | Buddhism News, Headlines | Thailand | Phra Prom returns to Erawan Shrine Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Arasu, S. T. (4 July 2020). "Galah Panjang and its Indian roots". On the sport. Be part of it. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Twenties: Reminiscing the dying art of Indonesian traditional children's games". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ See this page from the Indonesian Wikipedia for a list

- ^ Zoetmulder (1982:ix)

- ^ Khatnani, Sunita (11 October 2009). "The Indian in the Filipino". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015.

- OCLC 3061923.

- ^ Sharma, Sudhindra. "King Bhumibol and King Janak". nepalitimes.com. Himalmedia Private Limited. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

References

- Ali, Jason R.; Aitchison, Jonathan C. (2005), "Greater India", Earth-Science Reviews, 72 (3–4): 169–188,

- Azurara, Gomes Eannes de (1446), Chronica do Discobrimento e Conquista de Guiné (eds. Carreira and Pantarem, 1841), Paris

- Bayley, Susan (2004), "Imagining 'Greater India': French and Indian Visions of Colonialism in the Indic Mode", Modern Asian Studies, 38 (3): 703–744, S2CID 145353715

- JSTOR 1776846

- Caverhill, John (1767), "Some Attempts to Ascertain the Utmost Extent of the Knowledge of the Ancients in the East Indies", Philosophical Transactions, 57: 155–178, S2CID 186214598

- Coedes, George (1967), The Indianized States of Southeast Asia (PDF), Australian National University Press, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2019

- Coedès, George (1968), The Indianized States of South-East Asia, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1

- Guha-Thakurta, Tapati (1992), The making of a new 'Indian' art. Artists, aesthetics and nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850–1920, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- Handy, E. S. Craighill (1930), "The Renaissance of East Indian Culture: Its Significance for the Pacific and the World", Pacific Affairs, 3 (4), University of British Columbia: 362–369, JSTOR 2750560

- Keenleyside, T. A. (Summer 1982), "Nationalist Indian Attitudes Towards Asia: A Troublesome Legacy for Post-Independence Indian Foreign Policy", Pacific Affairs, 55 (2), University of British Columbia: 210–230, JSTOR 2757594

- Majumdar, R. C., H. C. Raychaudhuri, and Kalikinkar Datta (1960), An Advanced History of India, London: Macmillan and Co., 1122 pages

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Narasimhaiah, C. D. (1986), "The cross-cultural dimensions of English in religion, politics and literature", World Englishes, 5 (2–3): 221–230,

- JSTOR 2504471

- Wheatley, Paul (November 1982), "Presidential Address: India Beyond the Ganges—Desultory Reflections on the Origins of Civilisation in Southeast Asia", The Journal of Asian Studies, 42 (1), Association for Asian Studies: 13–28, S2CID 161697583

Further reading

- Language variation: Papers on variation and change in the Sinosphere and in the Indosphere in honour of James A. Matisoff, David Bradley, Randy J. LaPolla and Boyd Michailovsky eds., pp. 113–144. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Bijan Raj Chatterjee (1964), Indian Cultural Influence in Cambodia, University of Calcutta

- ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1

- Lokesh, Chandra, & International Academy of Indian Culture. (2000). Society and culture of Southeast Asia: Continuities and changes. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan.

- R. C. Majumdar, Study of Sanskrit in South-East Asia

- ISBN 81-7018-046-5.

- R. C. Majumdar, Champa, Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East, Vol.I, Lahore, 1927. ISBN 0-8364-2802-1

- R. C. Majumdar, Suvarnadvipa, Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East, Vol.II, Calcutta,

- R. C. Majumdar, Kambuja Desa or an Ancient Hindu Colony in Cambodia, Madras, 1944

- Daigorō Chihara (1996), Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-10512-6

- Hoadley, M. C. (1991). Sanskritic continuity in Southeast Asia: The ṣaḍātatāyī and aṣṭacora in Javanese law. Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Zoetmulder, P. J. (1982), Old Javanese-English Dictionary

External links

- Rethinking Tibeto-Burman – Lessons from Indosphere (archived 20 November 2007)

- THEORIES OF INDIANISATION Exemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia), by Dr. Helmut Lukas.