Individualist anarchism in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anarchism in the United States |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by

The first American anarchist publication was The Peaceful Revolutionist, edited by Warren, whose earliest experiments and writings predate Proudhon.

By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed.

Overview

For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, American

Contemporary individualist anarchist

Historian

Origins

Mutualism

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Mutualism is an

Mutualists argue for conditional titles to land, whose private ownership is legitimate only so long as it remains in use or occupation (which Proudhon called "possession").

Following Proudhon, mutualists are libertarian socialists who consider themselves to part of the

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist[2] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published,[4] an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates.[4]

Warren was a follower of

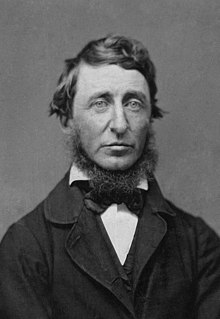

Henry David Thoreau

The American version of individualist anarchism has a strong emphasis on

"

Anarchism started to have an

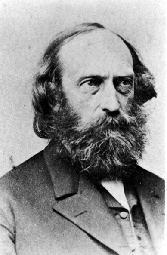

William Batchelder Greene

William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century

After 1850, Greene became active in labor reform.[37] Greene was "elected vice-president of the New England Labor Reform League, the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual banking, and in 1869 president of the Massachusetts Labor Union".[37] He then published Socialistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments (1875).[37] He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order."[37] His "associationism [...] is checked by individualism. [...] 'Mind your own business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands 'mutuality' in marriage – the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property".[37]

Stephen Pearl Andrews

Stephen Pearl Andrews was an individualist anarchist and close associate of Josiah Warren. Andrews was formerly associated with the Fourierist movement, but converted to radical individualism after becoming acquainted with the work of Warren. Like Warren, he held the principle of "individual sovereignty" as being of paramount importance.

Andrews said that when individuals act in their own self-interest, they incidentally contribute to the well-being of others. He maintained that it is a "mistake" to create a "state, church or public morality" that individuals must serve rather than pursuing their own happiness. In Love, Marriage and Divorce, and the Sovereignty of the Individual, he says to "[g]ive up [...] the search after the remedy for the evils of government in more government. The road lies just the other way – toward individualism and freedom from all government. [...] Nature made individuals, not nations; and while nations exist at all, the liberties of the individual must perish".

Contemporary American anarchist Hakim Bey reports that "Steven Pearl Andrews [...] was not a fourierist, but he lived through the brief craze for phalansteries in America & adopted a lot of fourierist principles & practices [...], a maker of worlds out of words. He syncretized Abolitionism, Free Love, spiritual universalism, [Josiah] Warren, & Fourier into a grand utopian scheme he called the Universal Pantarchy". Bey further states that Andrews was "instrumental in founding several 'intentional communities,' including the 'Brownstone Utopia' on 14th St. in New York, & 'Modern Times' in Brentwood, Long Island. The latter became as famous as the best-known fourierist communes (Brook Farm in Massachusetts & the North American Phalanx in New Jersey) – in fact, Modern Times became downright notorious (for 'Free Love') & finally foundered under a wave of scandalous publicity. Andrews (& Victoria Woodhull) were members of the infamous Section 12 of the 1st International, expelled by Marx for its anarchist, feminist, & spiritualist tendencies.[38]

Free love

An important current within American individualist anarchism is free love.[39] Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women such as with marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[39]

The most important American free love journal was

Lucifer the Lightbearer

According to Harman, the mission of

In February 1887, the editors and publishers of Lucifer were arrested after the journal ran afoul of the

In 1896, Lucifer was moved to Chicago, but legal harassment continued. The United States Postal Service—then known as the United States Post Office Department—seized and destroyed numerous issues of the journal and, in May 1905, Harman was again arrested and convicted for the distribution of two articles—"The Fatherhood Question" and "More Thoughts on Sexology" by Sara Crist Campbell. Sentenced to a year of hard labor, the 75-year-old editor's health deteriorated greatly. After 24 years in production, Lucifer ceased publication in 1907 and became the more scholarly American Journal of Eugenics.

They also had many opponents, and Moses Harman spent two years in jail after a court determined that a journal he published was "obscene" under the notorious

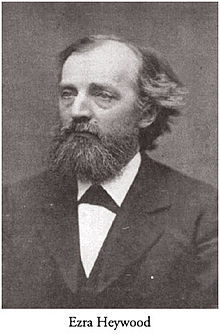

Ezra Heywood

The Word

M. E. Lazarus

In Lazarus' 1852 essay, Love vs Marriage, he argued that marriage as an institution was akin to "legalized prostitution", oppressing women and men by allowing loveless marriages contracted for economic or utilitarian reasons to take precedence over true love.[42][43][44]

Freethought

Freethought as a philosophical position and as activism was important in North American individualist anarchism. In the United States, freethought was "a basically

Boston anarchists

Another form of individualist anarchism was found in the United States as advocated by the Boston anarchists.[45] By default, American individualists had no difficulty accepting the concepts that "one man employ another" or that "he direct him," in his labor but rather demanded that "all natural opportunities requisite to the production of wealth be accessible to all on equal terms and that monopolies arising from special privileges created by law be abolished."[46]

They believed state monopoly capitalism (defined as a state-sponsored monopoly)[47] prevented labor from being fully rewarded. Voltairine de Cleyre, summed up the philosophy by saying that the anarchist individualists "are firm in the idea that the system of employer and employed, buying and selling, banking, and all the other essential institutions of Commercialism, centred upon private property, are in themselves good, and are rendered vicious merely by the interference of the State".[48]

Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including

Some Boston anarchists, including

Liberty (1881–1908)

Liberty was a 19th-century

Within the labor movement

Joseph Labadie was an American labor organizer,

Dyer Lum was a 19th-century American

Egoism

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract". After converting to egoist individualism, Tucker that "it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off. [...] Man's only right to land is his might over it."[63] In adopting Stirnerite egoism by 1886, Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. Tucker comments that "[s]o bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly".[64]

Wendy McElroy writes that "[s]everal periodicals were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism. They included: I published by C.L. Swartz, edited by W.E. Gordak and J.W. Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand, and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle 'A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology'.[64]

Among those American anarchists who adhered to egoism include Benjamin Tucker,

James L. Walker and The Philosophy of Egoism

James L. Walker, sometimes known by the pen name Tak Kak, was one of the main contributors to

Influence of Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Stirner were frequently compared by French "literary anarchists" and anarchist interpretations of Nietzschean ideas appear to have also been influential in the United States.[72] One researcher notes that "translations of Nietzsche's writings in the United States very likely appeared first in Liberty, the anarchist journal edited by Benjamin Tucker". He adds that "Tucker preferred the strategy of exploiting his writings, but proceeding with due caution: 'Nietzsche says splendid things, – often, indeed, Anarchist things, – but he is no Anarchist. It is of the Anarchists, then, to intellectually exploit this would-be exploiter. He may be utilized profitably, but not prophetably'".[73]

Italian Americans

Italian anti-organizationalist individualist anarchism was brought to the United States

Enrico Arrigoni

Enrico Arrigoni, pseudonym of Frank Brand, was an

Since 1945

A strong relationship does exist with post-left anarchism and the work of individualist anarchist

As far as posterior individualist anarchists,

In 1995, Lansdstreicher writing as Feral Faun wrote:

In the game of insurgence – a lived guerilla war game – it is strategically necessary to use identities and roles. Unfortunately, the context of social relationships gives these roles and identities the power to define the individual who attempts to use them. So I, Feral Faun, became [...] an anarchist, [...] a writer, [...] a Stirner-influenced, post-situationist, anti-civilization theorist, [...] if not in my own eyes, at least in the eyes of most people who've read my writings.[87]

Left-wing market anarchism, a form of

The genealogy of contemporary market-oriented left-libertarianism, sometimes labeled left-wing market anarchism,

See also

- Anarchism in the United States

- Individualist anarchism in Europe

- Individualist anarchism in France

References

- ^ a b c d e Wendy McElroy. "The culture of individualist anarchist in Late-nineteenth century America".

- ^ Slate.com.

- ^ JSTOR 2707055.

- ^ a b c Bailie, William (1906). Josiah Warren: The First American Anarchist – A Sociological Study Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Boston: Small, Maynard & Co. p. 20.

- ISBN 9780879260064

- ISBN 9781849351225.

- ^ Avrich, Paul. 2006. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press. p. 6.

- on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2020.. Retrieved 26 September 2020 – via the Mutualist: Free Market Anti-Capitalism website.

- ^ Eunice Minette Schuster. Native American Anarchism: A Study of Left-Wing American Individualism. Archived February 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kevin Carson. Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective. BookSurge. 2008. p. 1.

- ^ a b "G.1.4 Why is the social context important in evaluating Individualist Anarchism?" An Anarchist FAQ. Archived March 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Peter Sabatini. "Libertarianism: Bogus Anarchy".

- ^ "Introduction". Mutualist: Free-Market Anti-Capitalism. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Miller, David. 1987. "Mutualism." The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 11

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraph 15.

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraphs 9, 10 & 22.

- ^ Carson, Kevin, 2004, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, chapter 2 (after Meek & Oppenheimer).

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraph 19.

- ^ Carson, Kevin, 2004, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, chapter 2 (after Ricardo, Dobb & Oppenheimer).

- ^ Solution of the Social Problem, 1848–49.

- ^ Swartz, Clarence Lee. What is Mutualism? VI. Land and Rent

- ^ Hymans, E., Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, pp. 190–91,

Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Broadview Press, 2004, pp. 110, 112 - ^ General Idea of the Revolution, Pluto Press, pp. 215–16, 277

- ISBN 9780198277446. "The ownership [anarchists oppose] is basically that which is unearned [...] including such things as interest on loans and income from rent. This is contrasted with ownership rights in those goods either produced by the work of the owner or necessary for that work, for example his dwelling-house, land and tools. Proudhon initially refers to legitimate rights of ownership of these goods as 'possession,' and although in his latter work he calls this 'property,' the conceptual distinction remains the same."

- ISBN 9780429582363. "Ironically, Proudhon did not mean literally what he said. His boldness of expression was intended for emphasis, and by 'property' he wished to be understood what he later called 'the sum of its abuses'. He was denouncing the property of the man who uses it to exploit the labour of others without any effort on his own part, property distinguished by interest and rent, by the impositions of the non-producer on the producer. Towards property regarded as 'possession' the right of a man to control his dwelling and the land and tools he needs to live, Proudhon had no hostility; indeed, he regarded it as the cornerstone of liberty, and his main criticism of the communists was that they wished to destroy it."

- ^ "A Mutualist FAQ: A.4. Are Mutualists Socialists?". Mutualist: Free-Market Anti-Capitalism. Archived 9 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin (1926) [1890]. Individual Liberty: Selections from the Writings of Benjamin R. Tucker. New York: Vanguard Press. Archived 17 January 1999 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 September 2020 – via Flag.Blackened.Net.

- ^ Warren, Josiah. Equitable Commerce. "A watch has a cost and a value. The COST consists of the amount of labor bestowed on the mineral or natural wealth, in converting it into metals ..."

- ^ Madison, Charles A. (January 1945). "Anarchism in the United States". Journal of the History of Ideas. 6: 1. p. 53.

- ^ Diez, Xavier. L'ANARQUISME INDIVIDUALISTA A ESPANYA 1923–1938 p. 42.

- ^ Johnson, Ellwood. The Goodly Word: The Puritan Influence in America Literature, Clements Publishing, 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences, edited by Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman, Alvin Saunders Johnson, 1937, p. 12.

- ISBN 978-0-521-47675-1.

- ^ a b "RESISTING THE NATION STATE the pacifist and anarchist tradition by Geoffrey Ostergaard". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ a b c "Su obra más representativa es Walden, aparecida en 1854, aunque redactada entre 1845 y 1847, cuando Thoreau decide instalarse en el aislamiento de una cabaña en el bosque, y vivir en íntimo contacto con la naturaleza, en una vida de soledad y sobriedad. De esta experiencia, su filosofía trata de transmitirnos la idea que resulta necesario un retorno respetuoso a la naturaleza, y que la felicidad es sobre todo fruto de la riqueza interior y de la armonía de los individuos con el entorno natural. Muchos han visto en Thoreau a uno de los precursores del ecologismo y del anarquismo primitivista representado en la actualidad por Jonh Zerzan. Para George Woodcock(8), esta actitud puede estar también motivada por una cierta idea de resistencia al progreso y de rechazo al materialismo creciente que caracteriza la sociedad norteamericana de mediados de siglo XIX.""LA INSUMISIÓN VOLUNTARIA. EL ANARQUISMO INDIVIDUALISTA ESPAÑOL DURANTE LA DICTADURA Y LA SEGUNDA REPÚBLICA (1923–1938)" by Xavier Diez Archived May 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections by John Zerzan (editor)

- Hakim Bey. "The Lemonade Ocean & Modern Times".

- ^ a b c d e f g The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy

- ^ Joanne E. Passet, "Power through Print: Lois Waisbrooker and Grassroots Feminism," in: Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, James Philip Danky and Wayne A. Wiegand, eds., Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Press, 2006; pp. 229–50.

- ^ Biographical Essay by Dowling, Robert M. American Writers, Supplement XVII. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008

- ^ Freedman, Estelle B., "Boston Marriage, Free Love, and Fictive Kin: Historical Alternatives to Mainstream Marriage." Organization of American Historians Newsletter, August 2004. http://www.oah.org/pubs/nl/2004aug/freedman.html#Anchor-23702

- ^ Guarneri, Carl J., The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1991.

- ^ Stoehr, Taylor, ed., Free Love in America: A Documentary History. New York: AMS, 1979.

- ^ Levy, Carl. "Anarchism". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09.

- ^ Madison, Charles A. "Anarchism in the United States." Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol 6, No 1, January 1945, p. 53.

- ^ Schwartzman, Jack. "Ingalls, Hanson, and Tucker: Nineteenth-Century American Anarchists." American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 62, No. 5 (November 2003). p. 325.

- ^ de Cleyre, Voltairine. Anarchism. Originally published in Free Society, 13 October 1901. Published in Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine de Cleyre, edited by Sharon Presley, SUNY Press 2005, p. 224.

- ^ Spooner, Lysander. The Law of Intellectual Property Archived May 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 1, No. 4, p. 308.

- ISSN 0047-4517. pp. 5–6.

- ^ George Woodcock. Anarchism: a history of anarchist ideas and movements (1962). p. 459.

- ^ Brooks, Frank H. 1994. The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers. p. 75.

- ^ Stanford, Jim. Economics for Everyone: A Short Guide to the Economics of Capitalism. Ann Arbor: MI., Pluto Press. 2008. p. 36.

- ^ McKay, Iain. An Anarchist FAQ. AK Press. Oakland. 2008. pp 60.

- ^ McKay, Iain. An Anarchist FAQ. AK Press. Oakland. 2008. pp 22.

- ^ Woodcock, G. (1962). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Melbourne: Penguin. p. 460.

- ^ Martin, James J. (1970). Men Against the State: The Expositors of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908. Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher.

- ISBN 978-1-893626-21-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-24200-7.

- ^ Infoshop.org. Archived from the originalon 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ a b c d e Carson, Kevin. "May Day Thoughts: Individualist Anarchism and the Labor Movement". Mutualist Blog: Free Market Anti-Capitalism. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ Tucker, Instead of a Book, p. 350

- ^ a b c Wendy Mcelroy. "Benjamin Tucker, Individualism, & Liberty: Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order"

- ^ "Egoism" by John Beverley Robinson

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. The Debates of Liberty. Lexington Books. 2003. p. 55

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 163

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 165

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 166

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 164

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 167

- ^ O. Ewald, "German Philosophy in 1907", in The Philosophical Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, Jul., 1908, pp. 400–26; T. A. Riley, "Anti-Statism in German Literature, as Exemplified by the Work of John Henry Mackay", in PMLA, Vol. 62, No. 3, Sep., 1947, pp. 828–43; C. E. Forth, "Nietzsche, Decadence, and Regeneration in France, 1891–95", in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 54, No. 1, Jan., 1993, pp. 97–117; see also Robert C. Holub's Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist, an essay available online at the University of California, Berkeley website.

- ^ Robert C. Holub, Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm

- ^ Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. 1962

- ^ a b Enrico Arrigoni at the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia Archived May 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h [2]Paul Avrich. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America

- ^ Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm by Murray Bookchin

- ^ Anarchy after Leftism by Bob Black

- Jason McQuinn

- ^ "Theses on Groucho Marxism" by Bob Black

- ^ Immediatism by Hakim Bey. AK Press. 1994. p. 4 Archived December 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hakim Bey. "An esoteric interpretation of the I.W.W. preamble"

- ^ Anti-politics.net Archived 2009-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, "Whither now? Some thoughts on creating anarchy" by Feral Faun

- ^ Towards the creative nothing and other writings by Renzo Novatore Archived August 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The rebel's dark laughter: the writings of Bruno Filippi".

- ^ "The Last Word" by Feral Faun

- ^ Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia.

- ^ "It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism." Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. p. Back cover

- ^ "But there has always been a market-oriented strand of libertarian socialism that emphasizes voluntary cooperation between producers. And markets, properly understood, have always been about cooperation. As a commenter at Reason magazine's Hit&Run blog, remarking on Jesse Walker's link to the Kelly article, put it: "every trade is a cooperative act." In fact, it's a fairly common observation among market anarchists that genuinely free markets have the most legitimate claim to the label "socialism.""."Socialism: A Perfectly Good Word Rehabilitated" by Kevin Carson at website of Center for a Stateless Society

- ^ Carson, Kevin A. (2008). Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective. Charleston, SC:BookSurge.

- ^ Carson, Kevin A. (2010). The Homebrew Industrial Revolution: A Low-Overhead Manifesto. Charleston, SC:BookSurge.

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2000). Reason and Value: Aristotle versus Rand. Washington, DC:Objectivist Center

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2008). "An Interview With Roderick Long"

- ^ Johnson, Charles W. (2008). "Liberty, Equality, Solidarity: Toward a Dialectical Anarchism." Anarchism/Minarchism: Is a Government Part of a Free Country? In Long, Roderick T. and Machan, Tibor Aldershot:Ashgate pp. 155–88.

- ^ Spangler, Brad (15 September 2006). "Market Anarchism as Stigmergic Socialism Archived May 10, 2011, at archive.today."

- ^ Konkin III, Samuel Edward. The New Libertarian Manifesto Archived 2014-06-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Richman, Sheldon (23 June 2010). "Why Left-Libertarian?" The Freeman. Foundation for Economic Education.

- ^ Richman, Sheldon (18 December 2009). "Workers of the World Unite for a Free Market Archived July 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine." Foundation for Economic Education.

- ^ a b Sheldon Richman (3 February 2011). "Libertarian Left: Free-market anti-capitalism, the unknown ideal Archived 2012-05-09 at the Wayback Machine." The American Conservative. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (2000). Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism. University Park, PA:Pennsylvania State University Press.

- ^ Chartier, Gary (2009). Economic Justice and Natural Law. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Gillis, William (2011). "The Freed Market." In Chartier, Gary and Johnson, Charles. Markets Not Capitalism. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. pp. 19–20.

- ^ Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Gary Chartier and Charles W. Johnson (eds). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Minor Compositions; 1st edition (November 5, 2011)

- socialist tradition, and that market anarchists can and should call themselves "socialists." See Gary Chartier, "Advocates of Freed Markets Should Oppose Capitalism," "Free-Market Anti-Capitalism?" session, annual conference, Association of Private Enterprise Education (Cæsar's Palace, Las Vegas, NV, April 13, 2010); Gary Chartier, "Advocates of Freed Markets Should Embrace 'Anti-Capitalism'"; Gary Chartier, Socialist Ends, Market Means: Five Essays. Cp. Tucker, "Socialism."

- ^ Chris Sciabarra is the only scholar associated with this school of left-libertarianism who is skeptical about anarchism; see Sciabarra's Total Freedom

- ^ Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner. The origins of Left Libertarianism. Palgrave. 2000

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2006). "Rothbard's 'Left and Right': Forty Years Later." Rothbard Memorial Lecture, Austrian Scholars Conference.

- ^ Related, arguably synonymous, terms include libertarianism, left-wing libertarianism, egalitarian-libertarianism, and libertarian socialism.

- Sundstrom, William A. "An Egalitarian-Libertarian Manifesto Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine."

- Bookchin, Murray and Biehl, Janet (1997). The Murray Bookchin Reader. New York:Cassell. p. 170.

- Sullivan, Mark A. (July 2003). "Why the Georgist Movement Has Not Succeeded: A Personal Response to the Question Raised by Warren J. Samuels." American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 62:3. p. 612.

- doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.2005.00030.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ^ OCLC 750831024.

- ^ Schnack, William (13 November 2015). "Panarchy Flourishes Under Geo-Mutualism". Center for a Stateless Society. Archived 10 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Byas, Jason Lee (25 November 2015). "The Moral Irrelevance of Rent". Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Carson, Kevin (8 November 2015). "Are We All Mutualists?" Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Gillis, William (29 November 2015). "The Organic Emergence of Property from Reputation". Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Bylund, Per (2005). Man and Matter: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Justification of Ownership in Land from the Basis of Self-Ownership (PDF). LUP Student Papers (master's thesis). Lund University. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (1): 87–95.

- ^ Verhaegh, Marcus (2006). "Rothbard as a Political Philosopher" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (4): 3.

Further reading

- Brooks, Frank H. The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick. 1994.

- Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia.

- Men against the State: the expositors of individualist anarchism in America, 1827–1908 (1970) by James Joseph Martin.

- Native American Anarchism: A Study of Left-Wing American Individualism by Eunice Minette Schuster.

- Rocker, Rudolf. Pioneers of American Freedom: Origin of Liberal and Radical Thought in America. Rocker Publishing Committee. 1949.

- OCLC 37529250.