Indo-Saracenic architecture

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

Indo-Saracenic architecture (also known as Indo-Gothic, Mughal-Gothic, Neo-Mughal, in the 19th century often Indo-Islamic style

The style drew from western exposure to depictions of Indian buildings from about 1795, such as those by

The style enjoyed a degree of popularity outside British India, where architects often mixed Islamic and European elements from various areas and periods with boldness, in the prevailing climate of eclecticism in architecture. Among other British colonies and protectorates in the region, it was adopted by architects and engineers in British Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and the Federated Malay States (present-day Malaysia). The style was sometimes used, mostly for large houses, in the United Kingdom itself, for example at the royal Brighton Pavilion (1787–1823) and Sezincote House (1805) in Gloucestershire.

The wider European version, also popular in the Americas, is

Characteristics

With a number of exceptions from earlier, most Indo-Saracenic public buildings were constructed by parts of the British Raj government of India, in place between 1858 and 1947, with the peak period beginning around 1880. They partly reflected the British aspiration for an "Imperial style" of their own, rendered on an intentionally grand scale, reflecting and promoting a notion of an unassailable and invincible British Empire,[6] The style has been described as "part of a 19th-century movement to project themselves as the natural successors of the Mughals".[7]

At the same time they were built for modern functions such as railway stations, government offices for an increasingly wide-reaching bureaucracy, and law courts. They often incorporated modern construction methods and facilities. While stone was typically used, at least as a facing, these included substructures composed of iron, steel and

The style has been said, by a native of Kolkata,[who?] to be most common in "Southern and Western India", and of the three main cities of the 19th-century Raj, it was and is much more evident in Mumbai and Chennai rather than Kolkata, where both public government buildings, and the mansions of wealthy Indians tended to use versions of European Neoclassical architecture.[8] Madras (now Chennai) was a particular centre of the style, but still tended to use details from Mughal architecture, which had barely ever reached Tamil Nadu before. This was partly because English authorities such as James Fergusson especially deprecated Dravidian architecture,[9] which would also have been harder and more expensive to adapt to modern building functions.

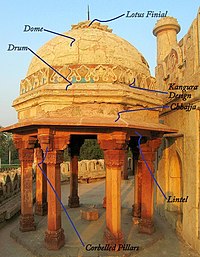

Typical elements found include:

- onion (bulbous) domes

- eaves, often supported by conspicuous brackets

- pointed arches, cusped arches, or scalloped arches

- Islamic Spainor North Africa, but often used

- contrasting colours of voussoirs round an arch, especially red and white; another feature more typical of North Africa and Spain

- curved roofs in Bengali styles such as char-chala

- domed chhatri kiosks on the roofline

- pinnacles

- towers or minarets

- open pavilions or pavilions with Bangala roofs

- jalis or openwork screens

- Mashrabiya or jharokha-style screened windows

- Iwans, in the form of entrances set back from the facade, under an arch.

Chief proponents of this style of architecture included

Structures built in Indo-Saracenic style in India and in certain nearby countries were predominantly grand public edifices, such as clock towers and courthouses. Likewise, civic as well as municipal and governmental colleges along with town halls counted this style among its top-ranked and most-prized structures to this day; ironically, in Britain itself, for example, King George IV's Royal Pavilion at Brighton, (which twice in its lifetime has been threatened with being torn-down, denigrated by some as a "carnival sideshow", and dismissed by threatened nationalists as "an architectural folly of inferior design", no less) and elsewhere, these rare and often diminutive (though sometimes, as mentioned, of grand-scale), residential structures that exhibit this colonial style are highly valuable and prized by the communities in which they exist as being somehow "magical" in appearance.[citation needed]

Typically, in India, villages, towns and cities of some means would lavish significant sums on construction of such architectural works when plans were drawn up for construction of the local

The cost involved in the construction of buildings of this style was high, including all their inherent customization, ornament and minutia decoration, the artisans' ingenious skills (stone and wood carving, as well as the exquisite lapidary/inlaid work) and usual accessibility to requisite raw materials, hence the style was executed only on buildings of a grand scale. However the occasional residential structure of this sort, (its being built in part or whole with Indo-Saracenic design elements/motifs) did appear quite often, and such buildings have grown ever more valuable and highly prized by local and foreign populations for their exuberant beauty and elegance today.[citation needed]

Either evidenced in a property's primary unit or any of its outbuildings, such estate-caliber residential properties lucky enough to boost the presence of an Indo-Saracenic structure, are still to be seen, generally, where in instances urban sprawl has not yet overcome them; often they are to be found in exclusive neighborhoods' (or surrounded, as cherished survivors, by enormous sky-scarpers, in more recently claimed urbanized areas throughout this "techno" driven, socio-economic revolutionary era marking India's recent decade's history), and are often locally referred to as "mini-palaces". Usually, their form-factors are these: townhouse, wings and/or porticoes. Additionally, more often seen are the diminutive renditions of the Indo-Saracenic style, built originally for lesser budgets, finding their nonetheless romantic expression in the occasional and serenely beautiful garden pavilion outbuildings, throughout the world, especially, in India and England.[citation needed]

Indian context

Confluence of different architectural styles had been attempted before during the mainly

Local influences also led to different 'orders' of the Indo-Islamic style. After the disintegration of the

Mughal style

Mughal architecture developed the

Decline and revival

Shah Jahan was succeeded by his son, Aurangzeb, who had little interest in art and architecture. As a result, Mughal commissioned architecture suffered, with most engineers, architects and artisans migrating to work under the patronage of local rulers. By the early 19th century, the British East India Company (EIC) controlled large portions of the Indian subcontinent. In 1803, their control was further strengthened after defeating the Maratha Empire which was led by Daulat Rao Sindhia. The EIC legitimized their rule by taking Mughal emperor Shah Alam II under their protection, and ruling in conjunction with him. However, their power was yet again challenged when in 1857 Indian soldiers in their employ, together with rebellious princes including Rani of Jhansi, launched the Indian Rebellion of 1857. However, this uprising was suppressed within a year and marked the end of the Mughal Empire, which was formally dissolved by the British. After the rebellion, the EIC's territories in India were formally transferred by the British government to Crown rule; the EIC dissolved soon after. In 1861, the new British colonial administration established the Archaeological Survey of India, gradually restoring several important Indian monuments (such as the Taj Mahal) over the following decades.[citation needed]

To usher in a new era, the British "Raj", a new architectural tradition was sought, marrying the existing styles of India with imported styles from the West, such as

The main building of Mayo College, completed in 1885, was built in the Indo-Saracenic style. Examples in Chennai include the Victoria Public Hall, Madras High Court, Senate House of the University of Madras, and the Chennai Central railway station. The building of New Delhi as the new imperial capital, which mostly took place between 1918 and 1931, led by Sir Edwin Lutyens, brought the last flowering of the style, using a deeper understanding of Indian architecture. The Rashtrapati Bhavan (Viceroy's, then President's Palace) uses elements from Buddhist-era Indian architecture as well as those from later periods. This can be seen in the capitals of the columns and the screen around the drum below the main dome, drawing on the railings placed around ancient stupas.[citation needed]

In British Malaya

According to Thomas R. Metcalf, a leading scholar of the style, "the Indo-Saracenic, with its imagined past turned to the purposes of British colonialism, took shape outside India [ie the subcontinent] most fully only in Malaya". British Malaya was a predominantly Muslim society, where there was hardly any recent tradition of building in brick or stone, with even mosques and the palaces of the local rulers built in the abundant local hardwoods. Kuala Lumpur was only a small settlement when in 1895 the British decided to make it the capital of their new Federated Malay States; it needed a number of large public buildings. The British decided to use the Islamic style they were used to from India, despite its having little relationship to existing local architectural styles.[11]

Unlike in India, the British also built some palaces for the sultans of the several

Contrary to what is sometimes claimed, the leading figures were English professional architects (whereas in India former soldiers or military engineers were often used) who had never worked in India. Usually they could design in both Indo-Saracenic and European styles. For example, the major buildings by

The Government Offices were the first major British commission in Malaya, and Bidwell had proposed a European style, but was over-ruled by

-

Kuala Kangsar, Perak

-

National Textile Museum in Kuala Lumpur, by Hubback, 1905. Originally as offices for the Federated Malay States Railways.

-

The Old High Court Building in Kuala Lumpur

-

Old Kuala Lumpur Town Hall, Hubback, 1896-1904

-

Jamek Mosque in Kuala Lumpur, by Hubback

-

Railway Administration Building, Kuala Lumpur

-

Kellie's Castle, Batu Gajah, Perak

Examples

India

-

The Taj Mahal Palace Hotelin Mumbai

-

Mumbai GPO, reminiscent of the Gol Gumbaz

-

Kachiguda Railway Station, Hyderabad

-

Raj Bhavan (backview), Kolkata

-

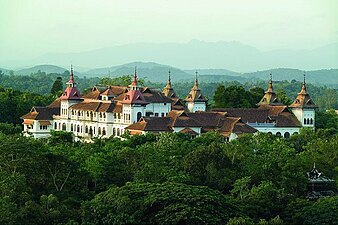

Kowdiar Palace, Kerala

-

Napier Museum, Kerala

Bangladesh

-

Curzon Hall in Dhaka

-

Uttara Gonobhaban

-

Masjid-e-Dewania in Chittagong

Pakistan

-

Karachi Metropolitan Corporation Building, Karachi, 1927–30

-

University of the Punjab, Lahore

-

Patiala Block of King Edward Medical University, Lahore

-

Karachi Chamber of Commerce Building

-

Darbar Mahal, Bahawalpur

-

Multan Clock Tower, Multan

-

National Academy of Performing Arts, Karachi

United Kingdom

-

Sezincote House, Gloucestershire, 1805

-

Royal Pavilion in Brighton, 1815–23

-

Western Pavilion in Brighton, 1828, designed by Amon Henry Wilds as his own home

-

Sunderland, 1877

-

Sassoon Mausoleum, now a chic Brighton supper club, 1892

Sri Lanka

-

Jami Ul-Alfar Mosque in Colombo

-

Jaffna Public Library in Jaffna

-

Jaffna Clock Tower in Jaffna

Elsewhere

-

Original Honkan, Tokyo National Museum, by Josiah Conder, largely destroyed by an earthquake in 1923

-

Palais du Bardo, parc Montsouris, Paris

Notes

- ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ^ Das, 98

- ^ Das, 95, 102

- ^ Jayewardene-Pillai, 10

- ^ Jayewardene-Pillai, 14

- ^ Jayewardene-Pillai, 6, 14

- ^ Das, xi

- ^ Das, xi, xiv, 98, 101

- ^ Das, 101–104

- ^ "Soudha: A tale of sweat and toil". Deccan Chronicle. 31 October 2010. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Metcalf

- ^ Metcalf

- The Encyclopedia of Malaysia(Architecture), p. 84–85.

- ^ Metcalf

- ^ Metcalf

- ^ Metcalf

- The Encyclopedia of Malaysia(Architecture), p. 82–83.

References

- Das, Pradip Kumar, Henry Irwin and the Indo Saracenic Movement Reconsidered, 2014, ISBN 1482822695, 9781482822694, google books

- Jayewardene-Pillai, Shanti, Imperial Conversations: Indo-Britons and the Architecture of South India, 2007, ISBN 8190363425, 9788190363426, google books

- Mann, Michael, "Art, Artefacts and Architecture" Chapter 2 in Civilizing Missions in Colonial and Postcolonial South Asia: From Improvement to Development, Editors: Carey Anthony Watt, Michael Mann, 2011, Anthem Press, ISBN 1843318644, 9781843318644, google books

- Metcalf, Thomas R., Imperial Connections: India in the Indian Ocean Arena, 1860–1920, 2007, University of California Press, ISBN 0520933338, 9780520933330, google books

Further reading

- Metcalf, Thomas R., An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain's Raj, 1989, University of California Press, ISBN 0520062353, 9780520062351