Inostrancevia

| Inostrancevia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of I. alexandri (PIN 1758), exposed at the Museo delle Scienze, Trento, Italy | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Gorgonopsia |

| Family: | †Gorgonopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Inostranceviinae |

| Genus: | †Inostrancevia Amalitsky, 1905 |

| Type species | |

| †Inostrancevia alexandri | |

| Other species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List of synonyms

| |

Inostrancevia is an

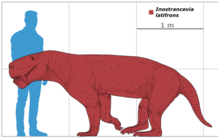

Inostrancevia is the biggest-known gorgonopsian, the largest fossil specimens indicating an estimated size between 3 m (9.8 ft) and 3.5 m (11 ft) long. The animal is characterized by its robust skeleton, broad skull and a very advanced dentition, possessing large canines, the longest of which can reach 15 cm (5.9 in) and probably used to shear the skin off its prey. Like most other gorgonopsians, Inostrancevia had a particularly large jaw opening angle, which would have allowed to deliver fatal bites.

First regularly classified as close to African taxa such as

Research history

Recognized species

During the 1890s, Russian paleontologist

The multiple administrative activities and difficult conditions during Amalitsky's last years have severely hampered his fossil research, leading to his unexpected death in 1917. However, among all the fossils identified before his death are two remarkably complete skeletons of large

It was in 1927 that one of Amalitsky's colleagues,

| External picture | |

|---|---|

In 1974,

The fourth known species, I. africana, was discovered from two specimens found between 2010 and 2011, respectively, by Nthaopa Ntheri and John Nyaphuli at Nooitgedacht Farm in the

Formerly assigned species and synonyms

Due to the poor quality of preservation of some Inostrancevia fossils, several specimens were therefore incorrectly found to belong to separate taxa. Only four species are recognized today, with three (I. alexandri, I. latifrons and I. uralensis) from Russia and one (I. africana) from South Africa.[2]

In his 1927 monograph, Pravoslavlev names two additional species of the genus Inostrancevia: I. parva and I. proclivis.[15] In 1940, the paleontologist Ivan Yefremov expressed doubts about this classification, and considered that the holotype specimen of I. parva should be viewed as a juvenile of the genus and not as a distinct species.[16][21] It was in 1953 that Boris Pavlovich Vyuschkov completely revised the species named for Inostrancevia. For I. parva, he moves it to a new genus, which he names Pravoslavlevia, in honor of the original author who named the species.[22] Although being a distinct and valid genus, Pravoslavlevia turns out to be a closely related taxon.[8][16][23][24] Also in his article, he considers that I. proclivis is a junior synonym of I. alexandri, but remains open to the question of the existence of this species, arguing his opinion with the insufficient preservation of type specimens.[22] This taxon will be definitively judged as being conspecific to I. alexandri in the revision of the genus carried out by Tatarinov in 1974.[25]

Also in is work, Pravoslavlev names another genus of gorgonopsians, Amalitzkia, with the two species it includes: A. vladimiri and A. annae, both named in reference to the pair of paleontologists who carried out the work on the first specimens known of I. alexandri.[15] In 1953, Vjuschkov discovered that the genus Amalitzkia is a junior synonym of Inostrancevia, renaming A. vladimiri to I. vladimiri,[22] before the latter was itself recognized as a junior synonym of I. latifrons by later publications.[26][8] For some unclear reason, Vjuschkov refers A. annae as a nomen nudum,[22] when his description is quite viable.[15] Just like A. vladimiri, A. annae will be synonymized with I. latifrons by Tatarinov in 1974.[26]

In 2003,

Other species belonging to distinct lineages were sometimes inadvertently classified in the genus Inostrancevia. For example, in 1940, Efremov classifies a gorgonopsian of then-problematic status as I. progressus.

Description

Inostrancevia is a gorgonopsian with a fairly robust morphology, the

The specimens PIN 2005/1578 and PIN 1758, belonging to I. alexandri, are among the largest and most complete gorgonopsian fossils identified to date. Both specimens are around 3 m (9.8 ft) long,[32] with the skulls alone measuring over 50 cm (20 in).[3] However, I. latifrons, although known from more fragmentary fossils, is estimated to have a more imposing size, the skull being 60 cm (24 in) long, indicating that it would have measured 3.5 m (11 ft) and weighed 300 kg (660 lb).[34] The size of I. uralensis is unknown due to very incomplete fossils, but it appears to be smaller than I. latifrons.[8]

Skull

The overall shape of the skull of Inostrancevia is similar to those of other gorgonopsians,

The jaws of Inostrancevia are powerfully developed, equipped with teeth able to hold and tear the

Postcranial skeleton

The skeleton of Inostrancevia is of very robust constitution, mainly at the level of the

Taxonomy

Classification

In the original description published in 1922, Inostrancevia was initially classified as a gorgonopsian close to the African genus

In 2018, in their description of Nochnitsa, Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin propose that all Russian and African taxa should be separately grouped into two distinct clades. For Russian genera (except basal taxa), this relationship is supported by notable cranial traits, such as the close contact between pterygoid and vomer. The discovery of other Russian gorgonopsians and the relationship between them and Inostrancevia has never before been recognized for the simple reason that some authors undoubtedly compared them to African genera.[16] The classification proposed by Kammerer and Masyutin will serve as the basis for all other subsequent phylogenetic studies of gorgonopsians.[23][24] As with previous classifications, Pravoslavlevia is still considered as the sister taxon of Inostrancevia.[16][23][24]

The following cladogram shows the position of Inostrancevia within the Gorgonopsia after Kammerer and Rubidge (2022):[24]

| Gorgonopsia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution

Gorgonopsians form a major group of carnivorous therapsids whose oldest-known representatives come from South Africa and appear in the fossil record from the

Paleobiology

Hunting strategy

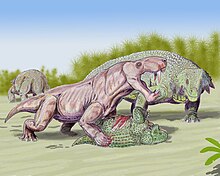

One of the most recognizable characteristics of Inostrancevia (and other gorgonopsians, as well) is the presence of long, saber-like canines on the upper and lower jaws. How these animals would have used this dentition is debated. The bite force of saber-toothed predators (like Inostrancevia), using three-dimensional analysis, was determined by Stephan Lautenschlager and colleagues in 2020:[48] their findings detailed that, despite morphological convergence among saber-toothed predators, there is a range of methods of possible killing techniques. The similarly-sized Rubidgea is capable of producing a bite force of 715 newtons; although lacking the necessary jaw strength to crush bone, the analysis found that even the most massive gorgonopsians possessed a more powerful bite than other saber-toothed predators.[49] The study also indicated that the jaw of Inostrancevia was capable of a massive gape, perhaps enabling it to deliver a lethal bite, and in a fashion similar to the hypothesised killing technique of Smilodon (or 'saber-toothed cat').[48]

Palaeoecology

European Russia

During the

The fossil sites from which Inostrancevia was recorded contain abundant fossils of terrestrial and shallow freshwater organisms, including

South Africa

According to the fossil record, the Upper Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone, from which I. africana is known, would have been a well-drained floodplain. The area preceding just before the Permian–Triassic extinction, this would explain why there is no more diversification of animals than in the older strata of the Balfour Formation.[2][54]

As in the other formations of the

Extinction

Gorgonopsians, including Inostrancevia, disappeared in the Late

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b Kukhtinov, D. A.; Lozovsky, V. R.; Afonin, S. A.; Voronkova, E. A. (2008). "Non-marine ostracods of the Permian-Triassic transition from sections of the East European platform". Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana. 127 (3): 717–726.

- ^ S2CID 258835757.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Amalitzky, V. (1922). "Diagnoses of the new forms of vertebrates and plants from the Upper Permian on North Dvina". Bulletin de l'Académie des Sciences de Russie. 16 (6): 329–340.

- ^ Benton et al. 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Gebauer 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Lankester 1905, p. 214-215.

- ^ Benton et al. 2000, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Benton et al. 2000, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c "Inostrancevia". Paleofile.

- ^ Gebauer 2007, p. 229.

- ^ a b Lankester 1905, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Greenfield, Tyler (26 December 2023). "Who named Inostrancevia?". Incertae Sedis.

- ^ S2CID 191313118.

- S2CID 133685968.

- ^ Akademii Nauk SSSR. pp. 1–117.

- ^ PMID 29900078.

- ^ S2CID 85114195.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 96-99.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 99.

- S2CID 82860920

- ^ Yefremov, Ivan (1940). "On the composition of the Severodvinian Permian Fauna from the excavation of V. P. Amalitzky". Academy of Sciences of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. 26: 893–896.

- ^ a b c d Vyushkov, Boris P. (1953). "On gorgonopsians from the Severodvinian Fauna". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 91: 397–400.

- ^ PMID 30485338.

- ^ S2CID 249977414.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 89.

- ^ a b Tatarinov 1974, p. 93.

- ^ a b Ivakhnenko, Mikhail F. (2003). "Eotherapsids from the East European placket (Late Permian)". Paleontological Journal. 37 (S4): 339–465.

- ^ PMID 26823998.

- ^ Bystrow, A. P. (1955). "A gorgonopsian from the Upper Permian beds of the Volga". Voprosy Paleontologii. 2: 7–18.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 62.

- ^ S2CID 140547244.

- ^ a b c d e Antón 2013, p. 79-81.

- PMID 27157809.

- S2CID 246318785.

- S2CID 8178585.

- ^ PMID 37434869.

- ^ ISBN 978-3437304873.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 82-83.

- ISSN 0031-0301.

- ^ Gebauer 2007, p. 232-232.

- PMID 26156768.

- ^ Antón 2013, p. 7-22.

- .

- S2CID 140601673.

- ^ S2CID 85512435.

- ^ a b c d Golubev, Valeriy K. (2000). "The faunal assemblages of Permian terrestrial vertebrates from Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal. 34 (2): 211–224.

- ^ a b Benton et al. 2000, p. 93-109.

- ^ PMID 32993469.

- S2CID 235487002.

- ^ S2CID 134260553.

- S2CID 140148404.

- ^ S2CID 59417568..

- ^ Benton et al. 2000, pp. 113–114.

- S2CID 134279628.

- S2CID 128991282.

- PMID 30177561.

- .

Bibliography

- OCLC 5984379.

- Tatarinov, Leonid P. (1974). Териодонты СССР [Theriodonts of the USSR] (in Russian). Vol. 143. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. pp. 1–226.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55476-3.

- Gebauer, Eva V. I. (2007). Phylogeny and Evolution of the Gorgonopsia with a Special Reference to the Skull and Skeleton of GPIT/RE/7113 (PDF) (PhD). Eberhard-Karls University of Tübingen. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012.

- OCLC 857070029.

External links

- Roman Uchytel. "Inostrancevia".