Insulin receptor

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 19: 7.11 – 7.29 Mb | Chr 8: 3.17 – 3.33 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

The insulin receptor (IR) is a

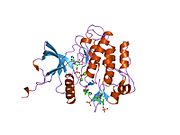

Structure

Initially,

Upon receptor dimerisation, after proteolytic cleavage into the α- and β-chains, the additional 12 amino acids remain present at the C-terminus of the α-chain (designated αCT) where they are predicted to influence receptor–ligand interaction.[9]

Each isometric monomer is structurally organized into 8 distinct domains consists of; a leucine-rich repeat domain (L1, residues 1–157), a cysteine-rich region (CR, residues 158–310), an additional leucine rich repeat domain (L2, residues 311–470), three fibronectin type III domains; FnIII-1 (residues 471–595), FnIII-2 (residues 596–808) and FnIII-3 (residues 809–906). Additionally, an insert domain (ID, residues 638–756) resides within FnIII-2, containing the α/β furin cleavage site, from which proteolysis results in both IDα and IDβ domains. Within the β-chain, downstream of the FnIII-3 domain lies a transmembrane helix (TH) and intracellular juxtamembrane (JM) region, just upstream of the intracellular tyrosine kinase (TK) catalytic domain, responsible for subsequent intracellular signaling pathways.[10]

Upon cleavage of the monomer to its respective α- and β-chains, receptor hetero or homo-dimerisation is maintained covalently between chains by a single disulphide link and between monomers in the dimer by two disulphide links extending from each α-chain. The overall 3D ectodomain structure, possessing four ligand binding sites, resembles an inverted 'V', with the each monomer rotated approximately 2-fold about an axis running parallel to the inverted 'V' and L2 and FnIII-1 domains from each monomer forming the inverted 'V's apex.[10][11]

Ligand binding

The insulin receptor's endogenous ligands include

Strictly speaking the relationship between IR and ligand shows complex allosteric properties. This was indicated with the use of a

These models state that each IR monomer possesses 2 insulin binding sites; site 1, which binds to the 'classical' binding surface of insulin: consisting of L1 plus αCT domains and site 2, consisting of loops at the junction of FnIII-1 and FnIII-2 predicted to bind to the 'novel' hexamer face binding site of insulin.[5] As each monomer contributing to the IR ectodomain exhibits 3D 'mirrored' complementarity, N-terminal site 1 of one monomer ultimately faces C-terminal site 2 of the second monomer, where this is also true for each monomers mirrored complement (the opposite side of the ectodomain structure). Current literature distinguishes the complement binding sites by designating the second monomer's site 1 and site 2 nomenclature as either site 3 and site 4 or as site 1' and site 2' respectively.[5][14] As such, these models state that each IR may bind to an insulin molecule (which has two binding surfaces) via 4 locations, being site 1, 2, (3/1') or (4/2'). As each site 1 proximally faces site 2, upon insulin binding to a specific site, 'crosslinking' via ligand between monomers is predicted to occur (i.e. as [monomer 1 Site 1 - Insulin - monomer 2 Site (4/2')] or as [monomer 1 Site 2 - Insulin - monomer 2 site (3/1')]). In accordance with current mathematical modelling of IR-insulin kinetics, there are two important consequences to the events of insulin crosslinking; 1. that by the aforementioned observation of negative cooperation between IR and its ligand that subsequent binding of ligand to the IR is reduced and 2. that the physical action of crosslinking brings the ectodomain into such a conformation that is required for intracellular tyrosine phosphorylation events to ensue (i.e. these events serve as the requirements for receptor activation and eventual maintenance of blood glucose homeostasis).[14]

Applying cryo-EM and molecular dynamics simulations of receptor reconstituted in nanodiscs, the structure of the entire dimeric insulin receptor ectodomain with four insulin molecules bound was visualized, therefore confirming and directly showing biochemically predicted 4 binding locations.[13]

Agonists

A number of

Signal transduction pathway

The insulin receptor is a type of

-

Effect of insulin on glucose uptake and metabolism. Insulin binds to its receptor (1), which, in turn, starts many protein activation cascades (2). These include: translocation of Glut-4 transporter to the plasma membrane and influx of glucose (3), glycogen synthesis (4), glycolysis (5), and fatty acid synthesis (6).

-

Signal transduction of Insulin: At the end of the transduction process, the activated protein binds to the PIP2 proteins embedded in the membrane.

Function

Regulation of gene expression

The activated IRS-1 acts as a secondary messenger within the cell to stimulate the transcription of insulin-regulated genes. First, the protein Grb2 binds the P-Tyr residue of IRS-1 in its

Stimulation of glycogen synthesis

Glycogen synthesis is also stimulated by the insulin receptor via IRS-1. In this case, it is the

Degradation of insulin

Once an insulin molecule has docked onto the receptor and effected its action, it may be released back into the extracellular environment or it may be degraded by the cell. Degradation normally involves

Immune system

Besides the metabolic function, insulin receptors are also expressed on immune cells, such as macrophages, B cells, and T cells. On T cells, the expression of insulin receptors is undetectable during the resting state but up-regulated upon T-cell receptor (TCR) activation. Indeed, insulin has been shown when supplied exogenously to promote in vitro T cell proliferation in animal models. Insulin receptor signalling is important for maximizing the potential effect of T cells during acute infection and inflammation.[19][20]

Pathology

The main activity of activation of the insulin receptor is inducing glucose uptake. For this reason "insulin insensitivity", or a decrease in insulin receptor signaling, leads to

Patients with insulin resistance may display acanthosis nigricans.

A few patients with homozygous mutations in the INSR gene have been described, which causes

Interactions

Insulin receptor has been shown to interact with

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000171105 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000005534 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ S2CID 27645596.

- S2CID 23230348.

- PMID 22355074.

- ^ PMID 19752219.

- PMID 21838706.

- ^ PMID 20348418.

- S2CID 4381431.

- ^ PMID 29453311.

- ^ PMID 31727777.

- ^ PMID 19225456.

- ^ PMID 4361269.

- S2CID 245242018.

- ISBN 0716730510.

- PMID 9793760.

- PMID 30174303.

- PMID 28115529.

- S2CID 15924838.

- S2CID 90238599. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- PMID 10615944.

- S2CID 25923169.

- PMID 8621530.

- PMID 7479769.

- PMID 9506989.

- PMID 9006901.

- S2CID 10955124.

- PMID 11606564.

- PMID 8626379.

- PMID 9092546.

- PMID 11266508.

- PMID 12031982.

- PMID 8135823.

- PMID 7493946.

- PMID 9742218.

- S2CID 21060861.

Further reading

- Pearson RB, Kemp BE (1991). "[3] Protein kinase phosphorylation site sequences and consensus specificity motifs: Tabulations". Protein kinase phosphorylation site sequences and consensus specificity motifs: tabulations. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 200. pp. 62–81. PMID 1956339.

- Joost HG (February 1995). "Structural and functional heterogeneity of insulin receptors". Cellular Signalling. 7 (2): 85–91. PMID 7794689.

- O'Dell SD, Day IN (July 1998). "Insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II)". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 30 (7): 767–71. PMID 9722981.

- Lopaczynski W (1999). "Differential regulation of signaling pathways for insulin and insulin-like growth factor I". Acta Biochimica Polonica. 46 (1): 51–60. PMID 10453981.

- Sasaoka T, Kobayashi M (August 2000). "The functional significance of Shc in insulin signaling as a substrate of the insulin receptor". Endocrine Journal. 47 (4): 373–81. PMID 11075717.

- Perz M, Torlińska T (2001). "Insulin receptor--structural and functional characteristics". Medical Science Monitor. 7 (1): 169–77. PMID 11208515.

- Benaim G, Villalobo A (August 2002). "Phosphorylation of calmodulin. Functional implications". European Journal of Biochemistry. 269 (15): 3619–31. PMID 12153558.

External links

- Insulin+receptor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P06213 (Insulin receptor) at the PDBe-KB.