Intracerebral hemorrhage

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cerebral haemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, intra-axial hemorrhage, cerebral hematoma, cerebral bleed, brain bleed, hemorrhagic stroke |

ventricular drain[1] | |

| Prognosis | 20% good outcome[2] |

| Frequency | 2.5 per 10,000 people a year[2] |

| Deaths | 44% die within one month[2] |

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as hemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into

Hemorrhagic stroke may occur on the background of alterations to the blood vessels in the brain, such as cerebral

The biggest risk factors for spontaneous bleeding are

Treatment should typically be carried out in an

Cerebral bleeding affects about 2.5 per 10,000 people each year.[2] It occurs more often in males and older people.[2] About 44% of those affected die within a month.[2] A good outcome occurs in about 20% of those affected.[2] Intracerebral hemorrhage, a type of hemorrhagic stroke, was first distinguished from ischemic strokes due to insufficient blood flow, so called "leaks and plugs", in 1823.[6]

Epidemiology

The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage is estimated at 24.6 cases per 100,000 person years with the incidence rate being similar in men and women.

Types

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage

Intraventricular hemorrhage

30% of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) are primary, confined to the ventricular system and typically caused by intraventricular trauma, aneurysm, vascular malformations, or tumors, particularly of the choroid plexus.

Signs and symptoms

People with intracerebral bleeding have symptoms that correspond to the functions controlled by the area of the brain that is damaged by the bleed.

A mnemonic to remember the warning signs of stroke is

Other symptoms include those that indicate a rise in intracranial pressure caused by a large mass (due to hematoma expansion) putting pressure on the brain.[15] These symptoms include headaches, nausea, vomiting, a depressed level of consciousness, stupor and death.[7] Continued elevation in the intracranial pressure and the accompanying mass effect may eventually cause brain herniation (when different parts of the brain are displaced or shifted to new areas in relation to the skull and surrounding dura mater supporting structures). Brain herniation is associated with hyperventilation, extensor rigidity, pupillary asymmetry, pyramidal signs, coma and death.[10]

Hemorrhage into the

Causes

Intracerebral bleeds are the second most common cause of

Risk factors for ICH include:[11]

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Menopause

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Severe migraine

Hypertension is the strongest risk factor associated with intracerebral hemorrhage and long term control of elevated blood pressure has been shown to reduce the incidence of hemorrhage.

Traumautic intracerebral hematomas are divided into acute and delayed. Acute intracerebral hematomas occur at the time of the injury while delayed intracerebral hematomas have been reported from as early as 6 hours post injury to as long as several weeks.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

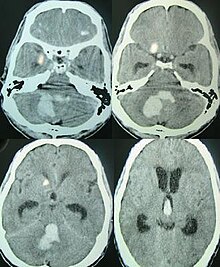

Both computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) have been proved to be effective in diagnosing intracranial vascular malformations after ICH.[12] So frequently, a CT angiogram will be performed in order to exclude a secondary cause of hemorrhage[30] or to detect a "spot sign".

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage can be recognized on CT scans because blood appears brighter than other tissue and is separated from the inner table of the skull by brain tissue. The tissue surrounding a bleed is often less dense than the rest of the brain because of edema, and therefore shows up darker on the CT scan.[30] The oedema surrounding the haemorrhage would rapidly increase in size in the first 48 hours, and reached its maximum extent at day 14. The bigger the size of the haematoma, the larger its surrounding oedema.[31] Brain oedema formation is due to the breakdown of red blood cells, where haemoglobin and other contents of red blood cells are released. The release of these red blood cells contents causes toxic effect on the brain and causes brain oedema. Besides, the breaking down of blood-brain barrier also contributes to the odema formation.[13]

Apart from CT scans, haematoma progression of intracerebral haemorrhage can be monitored using transcranial ultrasound. Ultrasound probe can be placed at the temporal lobe to estimate the volume of haematoma within the brain, thus identifying those with active bleeding for further intervention to stop the bleeding. Using ultrasound can also reduces radiation risk to the subject from CT scans.[14]

Location

When due to high blood pressure, intracerebral hemorrhages typically occur in the putamen (50%) or thalamus (15%), cerebrum (10–20%), cerebellum (10–13%), pons (7–15%), or elsewhere in the brainstem (1–6%).[32][33]

Treatment

Treatment depends substantially on the type of ICH. Rapid CT scan and other diagnostic measures are used to determine proper treatment, which may include both medication and surgery.

- Tracheal intubation is indicated in people with decreased level of consciousness or other risk of airway obstruction.[34]

- IV fluids are given to maintain fluid balance, using isotonic rather than hypotonic fluids.[34]

Medications

Rapid lowering of the blood pressure using

Giving

Frozen plasma, vitamin K, protamine, or platelet transfusions may be given in case of a coagulopathy.[34] Platelets however appear to worsen outcomes in those with spontaneous intracerebral bleeding on antiplatelet medication.[41]

The specific reversal agents idarucizumab and andexanet alfa may be used to stop continued intracerebral hemorrhage in people taking directly oral acting anticoagulants (such as factor Xa inhibitors or direct thrombin inhibitors).[7] However, if these specialized medications are not available, prothrombin complex concentrate may also be used.[7]

Only 7% of those with ICH are presented with clinical features of seizures while up to 25% of those have subclinical seizures. Seizures are not associated with an increased risk of death or disability. Meanwhile, anticonvulsant administration can increase the risk of death. Therefore, anticonvulsants are only reserved for those that have shown obvious clinical features of seizures or seizure activity on electroencephalography (EEG).[42]

H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors are commonly given to try to prevent stress ulcers, a condition linked with ICH.[34]

Surgery

Surgery is required if the

A

Aspiration by

A craniectomy holds promise of reduced mortality, but the effects of long‐term neurological outcome remain controversial.[46]

Prognosis

About 8 to 33% of those with intracranial haemorrhage have neurological deterioration within the first 24 hours of hospital admission, where a large proportion of them happens within 6 to 12 hours. Rate of haematoma expansion, perihaematoma odema volume and the presence of fever can affect the chances of getting neurological complications.[47]

The risk of death from an intraparenchymal bleed in traumatic brain injury is especially high when the injury occurs in the

For spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage seen on CT scan, the death rate (mortality) is 34–50% by 30 days after the injury,[22] and half of the deaths occur in the first 2 days.[51] Even though the majority of deaths occur in the first few days after ICH, survivors have a long-term excess mortality rate of 27% compared to the general population.[52] Of those who survive an intracerebral hemorrhage, 12–39% are independent with regard to self-care; others are disabled to varying degrees and require supportive care.[8]

References

- ^ PMID 26022637.

- ^ PMID 22974648.

- ^ a b "Brain Bleed/Hemorrhage (Intracranial Hemorrhage): Causes, Symptoms, Treatment".

- ^ ISBN 978-1416050094. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-02.

- PMID 29262429.

- ISBN 9781901346251. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-02.

- ^ S2CID 253159180.

- ^ S2CID 25364307.

- ISBN 978-0-8247-0104-8.

- ^ S2CID 21870062.

- ^ PMID 16081867.

- ^ PMID 25177839.

- ^ S2CID 7089563.

- ^ S2CID 7716659.

- ^ a b Vinas FC, Pilitsis J (2006). "Penetrating Head Trauma". Emedicine.com. Archived from the original on 2005-09-13.

- PMID 31839545.

- S2CID 36692451.

- PMID 9799012.

- PMID 10092713.

- ISSN 0029-6651.

- PMID 24842277.

- ^ PMID 17204141.

- PMID 23239837.

- ^ a b c McCaffrey P (2001). "CMSD 336 Neuropathologies of Language and Cognition". The Neuroscience on the Web Series. Chico: California State University. Archived from the original on 2005-11-25. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- ^ "Overview of Adult Traumatic Brain Injuries" (PDF). Orlando Regional Healthcare, Education and Development. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ Shepherd S (2004). "Head Trauma". Emedicine.com. Archived from the original on 2005-10-26. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- PMID 31266905.

- PMID 28178408.

- ISBN 978-0-521-87331-4.

- ^ PMID 19378710.

- PMID 21164136.

- ISBN 9781626232419.

- ISBN 978-1437709490. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Liebeskind DS (7 August 2006). "Intracranial Haemorrhage: Treatment & Medication". eMedicine Specialties > Neurology > Neurological Emergencies. Archived from the original on 2009-03-12.

- S2CID 45730236.

- S2CID 5871420.

- S2CID 54488358.

- PMID 26242330.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - S2CID 25397701.

- S2CID 30590573.

- PMID 37870112.

- PMID 25498578.

- S2CID 30210176.

- S2CID 27713031.

- ^ "Cerebral Hemorrhages". Cedars-Sinai Health System. Archived from the original on 2009-03-12. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- PMID 31887790.

- PMID 25657190.

- ^ Sanders MJ, McKenna K (2001). "Chapter 22: Head and Facial Trauma". Mosby's Paramedic Textbook (2nd revised ed.). Mosby.

- ^ Graham DI, Gennareli TA (2000). "Chapter 5". In Cooper P, Golfinos G (eds.). Pathology of Brain Damage After Head Injury (4th ed.). New York: Morgan Hill.

- S2CID 3107793.

- PMID 17478736.

- from the original on 2014-02-22.