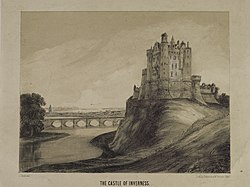

Inverness Castle

Inverness Castle (

History

Medieval history

A succession of castles have stood on this site since 1057.

In 1428, James I, in his effort to bring the Highlanders to heel, summoned fifty clan chiefs to a parley at Inverness Castle. However, "where the Parliament was at the time sitting, they were one by one by order of the King arrested, ironed, and imprisoned in different apartments and debarred from having any communications with each other or with their followers."[4] Several chiefs were executed on the spot. Among those arrested were Alexander, 3rd Lord of the Isles, and his mother, Mariota, Countess of Ross. Lord Alexander remained imprisoned for twelve months, after which he returned to Inverness with 10,000 men and burnt the town, though he failed to take the Castle.[5]

The castle was occupied during the

Mary, Queen of Scots

In 1548 another castle with tower was completed by

Mary, Queen of Scots came to Inverness in September 1562. She travelled from Aberdeen. She crossed the River Spey at Boharm by ferry boat. The boat cost 40 shillings and her almoner gave money to the poor folk in Boharm.[11] There was a wayside Hospital dedicated to St Nicholas at Boat o'Brig in Boharm,[12] a Spey crossing where there had formerly been a wooden bridge.[13]

George Buchanan states that when the unfortunate queen found the gates of Inverness Castle shut against her, "as soon as they heard of their sovereign's danger, a great number of the most eminent Scots poured in around her, especially the Frasers and Munros, who were esteemed the most valiant of the clans inhabiting those countries in the north". These two clans took Inverness Castle for the Queen, who had refused her admission. The Queen later hanged the governor, a Gordon who had refused entry.[14] George Buchanan's original writings state:[15]

Audito Principis periculo magna Priscorum Scotorum multitudo partim excita partim sua sponte afferit, imprimis Fraserie et Munoroii hominum fortissimorum in illis gentibus familiae.

which translates in English as:

That when they heard of their Sovereign's danger a great multitude of the ancient Scots poured in around her of their own volition, especially the Frasers and Munros, who were esteemed the most valiant families among those clans.

While Mary, Queen of Scots was in Inverness she bought gunpowder and 15 tartan plaids for her lackeys and members of her household.[16] Mary moved on to Speyside escorted by "captains of the Highland men", whose service cost £313-6s-8d Scots.[17]

Other sieges of Inverness Castle

There were later sieges of Inverness in 1562, 1649, 1650, 1689, 1715 and 1746.[18] Mary, Queen of Scots and Lord Darnley appointed Hucheon Rose of Kilravock keeper of the castle in September 1565. In October it was decided, the Earl of Huntly should be keeper.[19]

In May 1619 it was reported that Inverness Castle was in a poor state, and "a great part thereof was quite fallen down". King James wrote from Theobalds to the Earl of Mar and Gideon Murray with orders that the castle should be repaired as soon as priority works at Linlithgow Palace and Dumbarton Castle were completed. James thought that "although it may be that we in our own time shall never see it, much less dwell therein, yet may some of our successors take occasion to remain there". The castle was not repaired at this time.[20]

Current structure

The current structure was built on the site of the original castle.[21] The red sandstone structure, displaying an early castellated style, is the work of a few 19th-century architects. The main (southern), which incorporated the old County Buildings including the Sheriff Court, was designed by William Burn (1789–1870) in an early castellated, built in red sandstone and completed in 1836. The north block, which was originally used as a prison and later used as an additional courthouse, was designed by Thomas Brown II (1806–c. 1872) in a similar style, also built in red sandstone and was completed in 1848. Meanwhile, Joseph Mitchell (1803–1883) designed the bastioned enclosing walls.[22] The design of the main building involved a symmetrical main frontage of seven bays facing south. The central section of three bays, which slightly projected forward, involved a round headed doorway flanked by round headed windows on the ground floor, three round headed windows on the first floor and a battlement above. The outer bays took the form of castellated towers, the left-hand tower being round and the right-hand tower being square.[1]

Following the implementation of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889, which established county councils in every county, the new county leaders needed to identify a meeting place for Inverness-shire County Council[23] and duly arranged to meet in the courthouse.[24] After Inverness-shire County Council moved to its new headquarters in Glenurquhart Road in 1963, the building continued to serve a judicial function, being used for hearings of the sheriff's court and, on one day a month, for hearings of the justice of the peace court. However, hearings of the Inverness Sheriff Court were moved to the Inverness Justice Centre on 30 March 2020.[25][26]

Due to extensive renovation and remodelling the castle and grounds were closed to the public in 2021. The site is scheduled to re-open to the public in 2025.[27]

£50 note

An illustration of the castle has featured on the reverse side of a £50 note issued by the Royal Bank of Scotland, which was introduced in 2005.[28]

Gallery

-

Pipe band at Inverness Castle, 2014

-

Inverness Castle in winter with the statue of Flora MacDonald in the foreground

-

Inverness Castle

-

Inverness Castle as seen from across River Ness.

See also

- Banknotes of Scotland (featured on design)

- Sonnencroft

- North Coast 500, a scenic route which starts and ends at the castle

References

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Inverness Sheriff Court and Justice of the Peace Court, including Police Station and boundary wall, Castle Wynd, Castle Hill, Inverness (LB35166)". Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ISBN 978-1445642079.

- ^ Crome, Sarah, Scotland's First War of Independence (1999) at p. 101

- ^ Mackenzie, Alexander (1894). History of the Mackenzies. Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie. p. 69. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

1427.

- ISBN 978-9004279469. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 376.

- ^ Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1908), p. 278 no. 1820.

- ^ Charles Fraser Mackintosh, Antiquarian Notes: A Series of Papers Regarding Families and Places in the Higlands (Inverrness, 1865), pp. 25-26.

- ^ James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1913), p. 312.

- ^ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898). "XV. Robert Mor Munro". History of the Munros of Fowlis. Inverness: A. & W, Mackenzie. pp. 43-44.

Quoting: Register of the Great Seal, Book xxxi, No. 122.

- ^ Accounts of Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 16 (Edinburgh, 1916), pp. xli, 197.

- ^ L. Shaw, & J. F. S. Gordon, History of the Province of Moray, vol. 1, pp 78-79.

- ^ Boat O' Brig, Old Bridge, HES Canmore

- ^ "Clan MUNRO". www.electricscotland.com.

- ^ George Buchanan's (1506–1582), History of Scotland, completed in 1579, first published in 1582.

- ^ Clare Hunter, Embroidering Her Truth: Mary, Queen of Scots and the Language of Power (London: Sceptre, 2022), p. 155: Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1916), p. 197.

- ^ Gordon Donaldson, Accounts of the Collectors of Thirds of Benefices, 1561-1572 (Edinburgh: Scottish History Society, 1949), pp. 99-100: William Barclay Turnbull, Letters of Mary Stuart (London, 1845), p. xxxvi.

- ISBN 9780753822623.

- ^ Cosmo Innes, Genealogical deduction of the family of Rose of Kilravock (Aberdeen, 1848), pp. 244-6

- ^ HMC Mar & Kellie, vol. 1 (London, 1904), p. 86.

- ^ "Inverness Castle". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Inverness Castle". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Shennan, Hay (1892). Boundaries of Counties and Parishes in Scotland: as settled by the Boundary Commissioners under the Local Government (Scotland) Act, 1889. Edinburgh: William Green & Sons – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Highland Council Headquarters". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Inverness Justice Centre". www.scotcourts.gov.uk.

- ^ Andrew Dixon (30 March 2020). "See inside Scotland's first purpose-built justice centre which opened today in Inverness". Inverness Courier. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Work to transform Inverness Castle begins". The Highland Council. 13 April 2022.

- ^ "Current Banknotes : Royal Bank of Scotland". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 17 October 2008.