Iranian Armenians

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Armenian. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Persian. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 70,000–500,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Minority Shia Islam |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

|

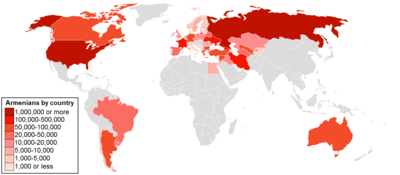

By country or region |

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| Persecution |

|

Iranian Armenians (

Armenians have lived for millennia in the territory that forms modern-day Iran. Many of the oldest Armenian churches, monasteries, and chapels are located within

Armenians were influential and active in the modernization of Iran during the 19th and 20th centuries. After the

History

This Section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

Since Antiquity there has always been much interaction between ancient

On the

The cultural links between the Armenians and the Persians can be traced back to Zoroastrian times. Prior to the 3rd century AD, no other neighbor had as much influence on Armenian life and culture as Parthia. They shared many religious and cultural characteristics, and intermarriage among Parthian and Armenian nobility was common. For twelve more centuries, Armenia was under the direct or indirect rule of the Persians.[6] While much influenced by Persian culture and religion, Armenia also retained its unique characteristics as a nation. Later, Armenian Christianity retained some Zoroastrian vocabulary and ritual.[citation needed]

In the 11th century, the Seljuk drove thousands of Armenians into Iran , where some were sold as slaves and others worked as artisans and merchants. After the Mongol conquest of Iran in the 13th century, many Armenian merchants and artists settled in Iran, in cities that were once part of historic Armenia such as Khoy, Salmas, Maku, Maragheh, Urmia, and especially Tabriz.[7]

Early modern to late modern era

Although Armenians have a long history of interaction and settlement with Persia/Iran and within the modern-day borders of the nation, Iran's Armenian community emerged under the

Shah Abbas

Bourvari (Armenian: Բուրւարի) is a collection of villages in Iran between the city of Khomeyn (Markazi province) and Aligudarz (Lorestan province). It was mainly populated by Armenians who were forcibly deported to the region by Shah Abbas of the Safavid Persian Empire during the same as part of Abbas's massive scorched earth resettlement policies within the empire.[13] The villages populated by the Armenians in Bourvari were Dehno, Khorzend, Farajabad, Bahmanabad and Sangesfid.

Loss of Eastern Armenia

From the late 18th century,

The Treaty of Turkmenchay further stipulated that the Tsar had the right to encourage the resettling of Armenians from Iran into the newly established Russian Armenia.[15][16] This resulted in a large demographic shift; many of Iran's Armenians followed the call, while many Caucasian Muslims migrated to Iran proper.

Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[17] At the close of the fourteenth century, after

After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[19] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. Some 35,000 Muslims out of more than 100,000 emigrated from the region, while some 57,000 Armenians from Iran proper and Turkey arrived after 1828[20] (see also Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829). As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[18] Not until after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, would ethnic Armenians once again establish a solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[21] Nevertheless, Erivan remained a Muslim-majority city up to the twentieth century.[21] According to the traveller H. F. B. Lynch, the city of Erivan was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Tatars[a] i.e. Azeris and Persians) in the early 1890s.[24]

With these events of the first half of the 19th century, and the end of centuries of Iranian rule over

Twentieth century up to 1979

The Armenians played a significant role in the development of 20th-century Iran, regarding both its economical as well as its cultural configuration.[26] They were pioneers in photography, theater, and the film industry, and also played a very pivotal role in Iranian political affairs.[26][27]

The Revolution of 1905 in Russia had a major effect on northern Iran and, in 1906, Iranian liberals and revolutionaries demanded a constitution in Iran. In 1909 the revolutionaries forced the crown to give up some of its powers. Yeprem Khan, an ethnic Armenian, was an important figure of the Persian Constitutional Revolution.[28]

Armenian Apostolic theologian

During the

The modernization efforts of Reza Shah (1924–1941) and Mohammad Reza Shah (1941–1979) gave the Armenians ample opportunities for advancement,

Armenian churches, schools, cultural centers, sports clubs and associations flourished and Armenians had their own senator and member of parliament, 300 churches and 500 schools and libraries served the needs of the community.

Armenian presses published numerous books, journals, periodicals, and newspapers, the prominent one being the daily "Alik".

After the 1979 Revolution

Many Armenians served in the

The fall of the Soviet Union, the common border with Armenia, and the Armeno-Iranian diplomatic and economic agreements have opened a new era for the Iranian Armenians. Iran remains one of Armenia's major trade partners, and the Iranian government has helped ease the hardships of Armenia caused by the blockade imposed by Azerbaijan and Turkey. This includes important consumer products, access to air travel, and energy sources (like petroleum and electricity).

Current status

The Armenians remain the largest

Distribution

This Section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

In 387 AD when the

The area retained a large Armenian population until 1914 when World War I began and Azerbaijan was invaded by the Ottomans who slaughtered much of the local Armenian population. Prior to the Ottoman invasion there were about 150,000 Armenians in Azerbaijan, and 30,000 of them were in Tabriz. About 80,000 were massacred, 30,000 fled to Russian Armenia, and the other 10,000 fled the area of the modern

This is a list of previously or currently Armenian inhabited settlements:

- Maku (Շավարշան / Shavarshan or Արտազ / Artaz (hy) in Armenian) now in Maku and Chalderan counties in West Azerbaijan Province:

- Maku, Qareh-Kelisa, Avajiq, Siah Cheshmeh, Shaveran, Sadal and Baron (Dzor Dzor).

- Khoy (Հեր / Her in Armenian) now in Khoy and Chaypareh (Avarayr Plain) counties in West Azerbaijan Province:

- West Azerbaijan Province:

- .

- Urmia (Ուրմիա / Urmia or Ուռմի / Urmi in Armenian) now in Urmia County in West Azerbaijan Province:

- Urmia, Balanej, Badelbo, Surmanabad, Jamalabad, Gardabad, Ikiaghaj, Isalu, Karaguz, Nakhichevan Tepe, Reihanabad, Sepurghan, Karabagh, Adeh, Dizej Ala, Khan Babakhan, Kachilan, Shirabad, Charbakhsh, Chahar Gushan, Ballu, Darbarud, ِDigala (fa), Kukia and Babarud.

- Julfa (Ջուղա / Jugha in Armenian):

- Upper Darashamb, Middle Darashamb and Lower Darashamb.

- East Azerbaijan Province:

- Tabriz (Թավրիզ / Tavriz or Թաւրէժ / Tavrezh in Armenian) now in Tabriz County in East Azerbaijan Province:

- Ardabil (Արտավիլ / Artavil or Արտավետ / Artavet in Armenian)

- Maragheh (Մարաղա / Maragha in Armenian)

- Miandoab:

- Taqiabad

Tabriz

Traditionally, Tabriz where Armenian political life vibrated from the early modern (Safavid) era and on.).

Notable Armenians from Tabriz

- Pre-Pahlavi period (pre-1925)

- Arakel of Tabriz, historian

- Mohammad Beg, statesman

- William Cormick, physician (half Armenian)

- Hayk Bzhishkyan, Soviet military commander (half Armenian)

- Ardashes Badmagrian, movie theater owner

- Hambarsoom Grigorian, composer

- Vartan Hovanessian, architect

- Ivan Galamian, violin teacher

- Hakob Karapents, author

- Gegham Saryan, poet and translator

- Vahan Papazian, political activist and community leader

- Avetis Nazarbekian, poet, journalist, political activist and revolutionary

- Louise Aslanian, writer and figure in the French Resistance

- Pahlavi and post-Pahlavi period (post-1925)

- Alexander Abian, mathematician

- Varto Terian, Iran's first stage actress of theater and educator

- Samuel Khachikian, film director, screenwriter, author, and film editor

- Arman (actor), actor, film director, producer

- Robert Ekhart, film director (half Armenian)

- Emik Avakian, inventor

- Khachik Babayan, violin player

- Grigor Vahramian Gasparbeg, painter

- Vartan Vahramian, composer, artist, and painter

- Vartan Gregorian, academic

- Vartan Hovanessian, architect

- Rouben Galichian, scholar

- Henry D. Sahakian, businessman

Central Iran

List of Armenian villages in central Iran:

- Markazi Province:

- Hamadan:

- Malayer:

- Anuch, Deh Chaneh and Qaleh Fattahieh.

- Kazaz (Kiazaz in Armenian) now in Shazand County in Markazi Province:

- Kamareh (Kiamara in Armenian) now in Khomeyn County in Markazi Province:

- Lorestan Province:

- Shapurabad, Khorzand, Parmishan, Pahra, Sang-e Sefid, Bahramabad, Dehnow, Qareh Kahriz, Nasrabad, Goran, Jowz, Cherbas, Jahan Khosh and Anuj.

- Japloq (hy) (Գյափլա / Giapla in Armenian) now in Azna County in Lorestan Province and Shazand County in Markazi Province:

- .

- Faridan (Փերիա / Isfahan Province:

- Zarneh (Boloran), Upper Khoygan, Nemagerd, Gharghan, Sangbaran, Hezar Jarib, Singerd, Lower Khoygan, Adegan, Chigan, Hadan, Milagerd, Surshegan, Savaran, Chigan, Derakhtak, Punestan, Qaleh Khajeh, Aznavleh, Bijgerd, Khong (now part of town of Fereydunshahr), Moghandar, Qalamelik, Nanadegan and Darreh Bid.

- Karvan, now in Tiran & Karvan Countyin Isfahan Province.

- Lenjan and Alenjan, now in Lenjan, Falavarjan and Mobarakeh counties in Isfahan Province:

- .

- Charmahal (Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province:

The settlements of Lenjan, Alenjan and Karvan were abandoned in the 18th century.

The other settlements depopulated in the middle of the 20th century due to emigration to New Julfa, Teheran or Soviet Armenia (in 1945 and later in 1967). Currently only 1 village (Zarneh) in Peria is totally, and 4 other villages (Upper Khoygan, Gharghan, Nemagerd and Sangbaran) in Peria and 1 village (Upper Chanakhchi) in Gharaghan are partially settled by Armenians.

Other than these settlements there is an Armenian village near Gorgan (Qoroq) which is settled by Armenians recently moved from Soviet territory.

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

In addition to having their own churches and clubs, Armenians of Iran are one of the few linguistic minorities in Iran with their own schools.[52][53] Armenians are exempt from national laws barring alcohol consumption and public gender relations in Armenian 'public' spaces, where Muslim citizens are not permitted to enter.[53]

Language: The Iranian Armenian dialect

The Armenian language used in Iran holds a unique position in the usage of Armenian in the world, as most Armenians in the Diaspora use

The Armenian dialects of Iran are referred to collectively in Armenian as Persian Armenian or Parskahayeren (պարսկահայերէն, պարսկահայերեն), or less commonly as Iranian Armenian or Iranahayeren (իրանահայերէն, իրանահայերեն).[53][54] The modern koine spoken in Tehran serves as the prestige dialect, although many historic varieties existed in Iranian Azerbaijan, Central Iran, Isfahan province, the New Julfa district in Isfahan, Kurdistan, Khorasan, and Khuzestan, some of which have persisted in their respective communities.[54] Iranian Armenian dialects are distinguished phonologically from other Eastern Armenian varieties by the widespread pronunciation of the retroflex approximant ⟨ɻ⟩ for ր, which sounds similar to the American English alveolar approximant ⟨ɹ⟩, while Armenian dialects outside of Iran pronounce it as a flap ⟨ɾ⟩.[54] Many dialects also use a low front vowel as a marginal phoneme ⟨æ⟩, primarily in loanwords from Persian, but also in some native Armenian words such as mæt "one; a bit; for a moment" from մի հատ mi hat.[53][54] There are also many calques from Persian, particularly in cultural phraseology and in compound verbs (e.g. պատճառ ելնել patčaṙ elnel from باعث شدن bā'es šodan “to result in; to cause”).[53]

See also

- Armenians in the Persianate, Iranian Armenia

- Christians in Iran

- List of Armenian churches in Iran

- Monasteries: Monastery of St. Thaddeus, Monastery of St. Stephen the Protomartyr

- Cathedrals: Holy Mother of God Cathedral, All Saviour's Cathedral, St. Sarkis Cathedral

- List of Iranian Armenians

- Media: Alik, Arax, Hooys

- Sports: Ararat Football Club, Ararat Basketball Club, Ararat Stadium, Pan-Armenian Games

- Politics: Armenian Revolutionary Federation in Iran

- Art: Lilihan carpets and rugs

Notes

- Transcaucasia.[22] Unlike Armenians and Georgians, the Tatars did not have their own alphabet and used the Perso-Arabic script.[22] After 1918 with the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and "especially during the Soviet era", the Tatar group identified itself as "Azerbaijani".[22] Prior to 1918 the word "Azerbaijan" exclusively referred to the Iranian province of Azarbayjan.[23]

References

- Open Society Institute.

Iran, which borders Armenia to the south, is home to an estimated 70,000–90,000 ethnic Armenians...

- ^ Vardanyan, Tamara (June 21, 2007). "Իրանահայ համայնք. ճամպրուկային տրամադրություններ [The Iranian-Armenian community]" (in Armenian). Noravank Foundation.

Հայերի թիվը հասնում է մոտ 120.000-ի։

- ^ Semerdjian, Harout Harry (January 14, 2013). "Christian Armenia and Islamic Iran: An unusual partnership explained". The Hill.

...the presence of a substantial Armenian community in Iran numbering 150,000.

- ISBN 9780230106352.

Today, the Armenian community in Iran numbers around 200,000...

- ISBN 978-0-415-49750-3.

Armenia has a population of 3 million with a 0.06 percent growth rate. The urbanization level is 64 percent. Yerevan, the capital, is the largest city at 1.1 million inhabitants, Gyumri has 160,000 and Vanadzor has 100,000. The population is 98 percent Armenian, with small percentages of Kurds and Russians. There is a great Armenian diaspora numbering 1 million in Russia, 500,000 in Iran, 500,000 in the USA, 400,000 in France and 300,000 in Georgia.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Armenian Iran history". Home.wanadoo.nl. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ISBN 1780230702p 165

- ISBN 1626160325p 43

- ISBN 9781135798376. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ a b H. Nahavandi, Y. Bomati, Shah Abbas, empereur de Perse (1587–1629) (Perrin, Paris, 1998)

- ^ "Armenia in the Age of Columbus". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ M. Canard: Armīniya in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Leiden 1993.

- ISBN 1598849484

- ^ "Griboedov not only extended protection to those Caucasian captives who sought to go home but actively promoted the return of even those who did not volunteer. Large numbers of Georgian and Armenian captives had lived in Iran since 1804 or as far back as 1795." Fisher, William Bayne;Avery, Peter; Gershevitch, Ilya; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles. The Cambridge History of Iran Cambridge University Press, 1991. p. 339.

- ^ (in Russian) A. S. Griboyedov. "Записка о переселеніи армянъ изъ Персіи въ наши области", Фундаментальная Электронная Библиотека

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11, 13–14.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, p. 14.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Bournoutian, George (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900–1914. Routledge. p. 35 (note 25).

- ^ Bournoutian, George (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900–1914. Routledge. p. xiv.

- ^ Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998, pp. 542–551.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger. Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 268.

- ^ a b Amurian, A.; Kasheff, M. (1986). "ARMENIANS OF MODERN IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c Arkun, Aram (1994). "DAŠNAK". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ Ormanian, Malachia (1911). Հայոց եկեղեցին և իր պատմութիւնը, վարդապետութիւնը, վարչութիւնը, բարեկարգութիւնը, արաողութիւնը, գրականութիւն, ու ներկայ կացութիւնը [The Church of Armenia: her history, doctrine, rule, discipline, liturgy, literature, and existing condition] (in Armenian). Constantinople. p. 266.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 9780871509635.

- ^ https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB5.1B.GIF [bare URL image file]

- ISBN 978-1568591414.

- ^ "Պատմություն | Հայրենադարձություն". Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Ibrahim, Youssef M. (December 10, 1978). "Moslem Revolt in Iran Stirs Fears for Future Of Minority Religions". The New York Times.

Yet, Archbishop Artak Manookian, the leader of Iran's 200,000 Armenians...

- ^ "Assessment for Christians in Iran". Minorities At Risk Project. 2006. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ISBN 9780160017292. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

There were an estimated 300,000 Armenians in the country at the time of the Revolution in 1979.

- ISBN 978-1139429856.

Armenians numbered an estimated 250,000 in 1979 (...)

- ^ Barry, James (2019). Armenian Christians in Iran: Ethnicity, Religion, and Identity in the Islamic Republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 5.

- ^ "Sarkis Cathedral, Tehran – Lonely Planet Travel Guide". Lonelyplanet.com. January 7, 2012. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ "Iran's religious minorities waning despite own MPs". Bahai.uga.edu. February 16, 2000. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ "Tehran – A Monument to Armenian Martyrs of the Iran-Iraq War". Art-A-Tsolum. October 3, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Square in Tehran Renamed After Armenian War Martyr". Financial Tribune. August 16, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Ayatollah Khamenei: Iran, Armenia should have solid, amicable ties despite U.S. opposition". Tehran Times. February 27, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ Golnaz Esfandiari (December 23, 2004). "A Look At Iran's Christian Minority". Payvand. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Barry, James (2019). Armenian Christians in Iran: Ethnicity, Religion, and Identity in the Islamic Republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 4.

- ^ "Իրանի Կրոնական Փոքրամասնություններ". Lragir.am. June 30, 2013. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ Իրանահայ «Ալիք»- ը նշում է 80- ամյակը

- ^ Թամարա Վարդանյան. "Իրանահայ Համայնք. Ճամպրուկային Տրամադրություններ". Noravank.am. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ Հայկական Հանրագիտարան. "Հայերն Իրանում". Encyclopedia.am. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ISBN 978-9004262577

- ^ ISBN 978-3447043090

- ^ "Edmon Armenian history". Home.wanadoo.nl. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharifzadeh, Afsheen (August 25, 2015). "On "Parskahayeren", or the Language of Iranian Armenians". Borderlessblogger.com.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-96110-419-2.

Sources

- Bournoutian, George A. (1980). "The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826–1832". The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies.)

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help - Yves Bomati and Houchang Nahavandi,Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia,1587–1629, 2017, ed. Ketab Corporation, Los Angeles, ISBN 978-1595845672, English translation by Azizeh Azodi.

- Amurian, A.; Kasheff, M. (1986). "ARMENIANS OF MODERN IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- Berberian, Houri (2008). "ARMENIA ii. ARMENIAN WOMEN IN THE LATE 19TH- AND EARLY 20TH-CENTURY PERSIA". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: ISBN 0521200954.

- Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. (1998). "EREVAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 542–551.

Further reading

- Yaghoobi, Claudia (2021). "Racial Profiling of Iranian Armenians in the United States: Omid Fallahazad's "Citizen Vartgez"". Iran Namag. 6 (2).

- Yengimolki, A. (2023). The Emergence of a New Identity: Armenians in Safavid Isfahan. Journal of Religious Minorities under Muslim Rule, 1(2), 161-179. https://doi.org/10.1163/27732142-bja00007