Irish revolutionary period

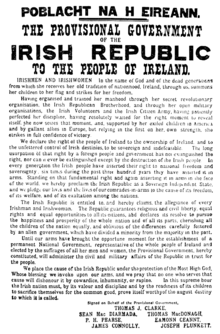

The Birth of the Irish Republic; painting by Walter Paget | |

| Native name | Tréimhse Réabhlóideach in Eirinn |

|---|---|

| Date | 1912 to 1923 |

| Location | Ireland |

| Outcome | Partition of Ireland; Anglo-Irish Treaty; establishment of Irish Free State and Northern Ireland |

The revolutionary period in

Some modern historians define the revolutionary period as the period from the introduction of the

The early years of the Free State, when it was governed by the pro-

Overview

Home Rule seemed certain in 1910 when the

In September 1914, two months after the

The period 1916–1921 was marked by political violence and upheaval, ending in the

Unwilling to negotiate any understanding with Britain short of complete independence, the

Timeline

- 1911: Parliament Act 1911 restricts House of Lords' power to veto Home Rule[9]

- 1912: Third Home Rule Bill introduced at Westminster; Ulster Covenant signed by unionist opponents of Home Rule[10]

- 1913: Dublin lock-out labour dispute[11]

- 1914: First World War breaks out; Third Home Rule Bill enacted but suspended for the duration of the war[12]

- 1915: Patrick Pearse's graveside panegyric at the funeral of Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa: "Ireland unfree shall never be at peace"[13]

- 1916: Easter Rising by republicans; Battle of the Somme in which Irish soldiers feature prominently, including the mostly unionist 36th (Ulster) Division and nationalist 16th (Irish) Division

- 1917: Irish Convention fails to find a political compromise[14]

- 1918: Conscription Crisis; First World War ends; general election sees Sinn Féin eclipse Irish Parliamentary Party[15]

- 1919: Irish Republican Army starts Irish War of Independence (aka "Anglo-Irish War", or "Black and TanWar")

- 1920: Southern Ireland

- 1921: Ceasefire in War of Independence; Government of Northern Ireland takes office; UK and Dáil governments sign Anglo-Irish Treaty[16]

- 1922: Provisional Government begins administration in what becomes the Irish Free State; Irish Civil War begins between Free State and anti-Treaty republicans[17]

- 1923: Free State wins the Civil War

- 1924: Army Mutiny suppressed

- 1925: Collapse of Irish Boundary Commission means 1920 boundary becomes permanent

- 1926: Fianna Fáil splits from anti-Treaty Sinn Féin

- 1927: Fianna Fáil enters the Dáil after disputably subscribing to the Oath of Allegiance, becoming a "slightly constitutional party".[18]

Commemoration

Separate unionist and nationalist historical narratives exist for the historic events in question; nationalist perspectives are further divided by the Civil War which ended the revolutionary period. The Northern Ireland peace process, with its promotion of dialogue and reconciliation, has modified this separation.[19][20] The Bureau of Military History established by the Irish government in 1947 collected oral history accounts from republican veterans of the period 1913 to 1921. Its records were sealed until the last veteran's death in 2003; they were published online in 2012.[21]

In May 2010, the Institute for British Irish Studies in University College Dublin organised a conference on the theme A Decade of Centenaries: Commemorating Our Shared History.[22] Taoiseach Brian Cowen addressed the conference:[23]

This coming decade of commemorations, if well prepared and carefully considered, should enable all of us on this island to complete the journey we have started towards lasting peace and reconciliation. Twelve years have passed since the [Good Friday] Agreement. In the next twelve years we will witness a series of commemorations which will give us pause to reflect on where we have come from, and where we are going. With the centenaries of the Ulster Covenant, the Battle of the Somme, the Easter Rising, the War of Independence, the Government of Ireland Act and the Treaty, the events which led to the political division of this island come up for re-examination. We will also reflect on the crucial roles played by the Labour movement in that defining decade.

He later said "We believe that mutual respect should be central to all commemorative events and that historical accuracy should be paramount."[24]

The

On 27 February 2012, the Northern Ireland Assembly passed a motion:[26]

That this Assembly notes the number of centenaries of significant historic events affecting the UK and Ireland in the next 10 years; calls on

Minister of Enterprise, Trade and Investmentto work together, with the British and Irish Governments, to develop a co-ordinated approach to the commemoration of these important events in our shared history.

An All-Party Oireachtas Consultation Group on Commemorations exists,[27] with an "Expert Advisory Group of eminent historians".[28] In April 2012, the National Commemorative Programme for the Decade of Centenaries, covering centenaries from 1912 to 1922, was announced in the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht under minister Jimmy Deenihan.[29] In June, Deenihan stated that consideration will initially be focused up to 2016, centenary of the Easter Rising.[30]

Hugo Swire told the UK parliament in May 2012 that the Northern Ireland Office was consulting with the Northern Ireland Executive and the Irish government, saying "All these discussions underpin the need to promote tolerance and mutual understanding to ensure that these anniversaries are commemorated with tolerance, dignity and respect for all."[31]

In a debate on the programme in the

A series of conferences, Reflecting on a decade of War and Revolution in Ireland 1912–1923 was organised by Universities Ireland starting in June 2012.[33]

Century Ireland is a website launched in May 2013 to track events as their centenaries pass, using both period documents and modern commentary. It is produced by Boston College's 'Center for Irish Programs', and is funded by the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht and hosted by RTÉ.ie.[34][35]

References

- ISBN 9781908996176. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ "Atlas of the Irish Revolution is mammoth and magnificent". The Irish Times. 16 September 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ISBN 9781317801474. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ "Ireland: Revolutionary Period, 1916–1924". britishpathe.com. British Pathé. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ISBN 0312227272.

- ^ a b "From brink of civil war". The Irish Times. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ISBN 978-1408279106.

- ^ "Declaration of independence – Reprinted from Minutes and Proceedings of the First Dáil". Documents on Irish Foreign Policy. National Archives of Ireland. 21 January 1919. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Parliament Act 1911: Introduction". legislation.gov.uk. UK National Archives. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "The 1912 Ulster Covenant by Joseph E.A. Connell Jr". historyireland.com. History Ireland Magazine. 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "The Lockout of 1913". The Irish Times. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Government of Ireland Act 1914". parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Ireland unfree shall never be at peace". Century Ireland. RTÉ. 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Irish Convention comes to a close". Century Ireland. RTÉ. 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Remembering 1918 in Ireland". rte.ie. RTÉ. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Anglo-Irish Treaty – 6 December 1921". nationalarchives.ie. National Archives. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "1921–22: The Irish Free State and civil war". The Search for Peace. BBC. 18 March 1999. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Fianna Fáil & Arms Decommissioning 1923–32". historyireland.com. History Ireland Magazine. 1997. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- S2CID 159868830.

- ^ Boland, Rosita (25 June 2012). "Caution against 'glory' commemorations as centenary of crucial decade beckons". The Irish Times. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Bureau of Military History 1913–1921". Dublin: Military Archives and National Archives. 2012. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "IBIS Annual Conference 2010". UCD: Institute for British Irish Studies. May 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ ""A Decade of Commemorations Commemorating Our Shared History" Speech by An Taoiseach, Mr Brian Cowen TD Institute for British Irish Studies UCD, 20 May 2010 at 11.00am". Department of the Taoiseach. pp. Taoiseach's Speeches 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Ceisteanna – Questions – Northern Ireland Issues". Dáil Éireann debates. Oireachtas. 23 June 2010. pp. Vol.713 No.2 p.6. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Peace Process: Discussion". Joint Committee on the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement. Oireachtas. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Private Members' Business: Decade of Centenaries". Hansard. Northern Ireland Assembly. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Written Answers – Commemorative Events". Dáil Éireann debates. Oireachtas. 6 March 2012. pp. Vol.758 No.1 p.47. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Written Answers – Commemorative Events". Dáil Éireann debates. Oireachtas. 1 May 2012. pp. Vol.763 No.3 p.31. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Minister Deenihan addresses Presbyterian Conference in Belfast" (Press release). Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Written Answers – Commemorative Events". Dáil debates. Oireachtas. 6 June 2012. pp. Vol.767 No.1 p.44. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Written Answers to Questions: Dealing with the Past". House of Commons Hansard. 17 May 2012. pp. c 232W–233W. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Decade of Commemorations: Statements". Seanad Éireann debates. 7 June 2012. pp. Vol.215 No.14 p.5. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Conference: Reflecting on a decade of War and Revolution in Ireland 1912–1923: Historians and Public History". News & Events. Universities Ireland. 16 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Press Association (10 May 2013). "Virtual history newspaper goes live". Irish Independent. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "About Century Ireland". Century Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: RTÉ.ie. May 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

Further reading

- Coleman, Marie. The Irish Revolution, 1916–1923 (2013)

- Cottrell, Peter. The War for Ireland: 1913 – 1923 (2009)

- Curran, Joseph Maroney. The Birth of the Irish Free State, 1921–1923 (Univ of Alabama Press, 1980)

- Ferriter, Diarmaid. A Nation and not a Rabble: The Irish Revolutions 1913–1923 (2015)

- Gillis, Liz (2014). Women of the Irish Revolution. Cork: Mercier Press. ISBN 978-1-78117-205-6.

- Hanley, Brian. The IRA: A Documentary History 1916-2005 (Gill & Macmillan, 2010)

- Hart, Peter. "The geography of revolution in Ireland 1917-1923." Past and Present (1997): 142–176. JSTOR

- Knirck, Jason K. Imagining Ireland's independence: the debates over the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006)

- Laffan, Michael. The resurrection of Ireland: the Sinn Féin party, 1916–1923 (Cambridge University Press, 1999)

- Leeson, David M. The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920–1921 (Oxford University Press, 2011)

- Townshend, Charles. The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence 1918–1923 (2014)

External links

- "Decade of Centenaries". Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht p. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- "Decade of Centenaries". University College Dublin.

- "Century Ireland". RTÉ.

- Irish Military Archives, includes various digitised collections of documents from the revolutionary period