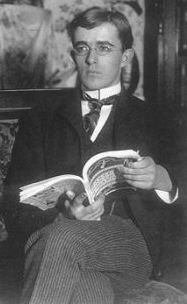

Irving Langmuir

Irving Langmuir | |

|---|---|

Langmuir waves | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry, physics |

| Institutions | Stevens Institute of Technology General Electric |

| Thesis | Ueber partielle wiedervereinigung dissociierter gase im verlauf einer Abkühlung (1909) |

| Doctoral advisor | Friedrich Dolezalek |

| Other academic advisors | Walther Nernst |

Irving Langmuir (

Langmuir's most famous publication is the 1919 article "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules" in which, building on

Biography

Early years

Irving Langmuir was born in Brooklyn, New York, on January 31, 1881. He was the third of the four children of Charles Langmuir and Sadie, née Comings. During his childhood, Langmuir's parents encouraged him to carefully observe nature and to keep a detailed record of his various observations. When Irving was eleven, it was discovered that he had poor eyesight.[5] When this problem was corrected, details that had previously eluded him were revealed, and his interest in the complications of nature was heightened.[6]

During his childhood, Langmuir was influenced by his older brother, Arthur Langmuir. Arthur was a research chemist who encouraged Irving to be curious about nature and how things work. Arthur helped Irving set up his first chemistry lab in the corner of his bedroom, and he was content to answer the myriad questions that Irving would pose. Langmuir's

Education

Langmuir attended several schools and institutes in America and Paris (1892–1895) before graduating high school from

Research

His initial contributions to science came from his study of light bulbs (a continuation of his PhD work). His first major development was the improvement of the diffusion pump, which ultimately led to the invention of the high-vacuum rectifier and amplifier tubes. A year later, he and colleague Lewi Tonks discovered that the lifetime of a tungsten filament could be greatly lengthened by filling the bulb with an inert gas, such as argon, the critical factor (overlooked by other researchers) being the need for extreme cleanliness in all stages of the process. He also discovered that twisting the filament into a tight coil improved its efficiency. These were important developments in the history of the incandescent light bulb. His work in surface chemistry began at this point, when he discovered that molecular hydrogen introduced into a tungsten-filament bulb dissociated into atomic hydrogen and formed a layer one atom thick on the surface of the bulb.[9]

His assistant in vacuum tube research was his cousin William Comings White.[10]

As he continued to study filaments in vacuum and different gas environments, he began to study the emission of charged particles from hot filaments (

He introduced the concept of electron temperature and in 1924 invented the diagnostic method for measuring both temperature and density with an electrostatic probe, now called a Langmuir probe and commonly used in plasma physics. The current of a biased probe tip is measured as a function of bias voltage to determine the local plasma temperature and density. He also discovered atomic hydrogen, which he put to use by inventing the atomic hydrogen welding process; the first plasma weld ever made. Plasma welding has since been developed into gas tungsten arc welding.

In 1917, he published a paper on the chemistry of oil films

Later years

Following

Langmuir was president of the Institute of Radio Engineers in 1923.[17]

Based on his work at General Electric,

He joined

After observing windrows of drifting seaweed in the Sargasso Sea he discovered a wind-driven surface circulation in the sea. It is now called the Langmuir circulation.

During

In 1953 Langmuir coined the term "

His house in Schenectady, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Personal life

Langmuir was married to Marion Mersereau (1883–1971) in 1912 with whom he adopted two children: Kenneth and Barbara. After a short illness, he died in Woods Hole, Massachusetts from a heart attack on August 16, 1957. His obituary ran on the front page of The New York Times.[19]

On his religious views, Langmuir was an agnostic.[20]

In fiction

According to author Kurt Vonnegut, Langmuir was the inspiration for his fictional scientist Dr. Felix Hoenikker in the novel Cat's Cradle,[21] and the character's invention of ice-nine, a new phase of water ice (similar in name only to Ice IX). Langmuir had worked with Vonnegut's brother, Bernard Vonnegut at General Electric on seeding ice crystals to diminish or increase rain or storms.[22][23][24]

Honors

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1918)[25]

- Member of the United States National Academy of Sciences (1918)[26]

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (1922)[27]

- Perkin Medal (1928)[28]

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1932)

- Franklin Medal (1934)

- Faraday Medal(1944)

- National Academy of Sciences (1950)[29]

- Mount Langmuir [1] [2] (elevation 8022 ft / 2445m ) in Alaska is named after him (Chugach National Forest, Copper River, AK)

- Langmuir College, a residential college at Stony Brook University in H-Quad, named for him in 1970 [3] [4]

- grandson, Roger R Summerhayes, directed/wrote/produced/edited a 57-minute documentary in 1999 called Langmuir's World [5]

Patents

- Langmuir, U.S. patent 1,180,159, "Incandescent Electric Lamp"

- Langmuir, U.S. patent 1,244,217, "Electron-discharge apparatus and method of operating the same"

- Langmuir, U.S. patent 1,251,388, "Method of and apparatus for controlling x-ray tubes"

See also

- 18-electron rule

- Irving Langmuir House

- Langmuir isotherm

- Langmuir trough

- Langmuir equation, an equation that relates the coverage or adsorption of molecules on a solid surface to gas pressure or concentration of a medium above the solid surface at a fixed temperature

- Langmuir wave, a rapid oscillation of the electron density in conducting media such as plasmas or metals

- Langmuir states, three-dimensional quantum states of Helium when both electrons move in phase on Bohr circular orbits and mutually repel

- Langmuir–Blodgett film

- Child–Langmuir law

- Langmuir–Taylor detector

- List of things named after Irving Langmuir

References

- ^ S2CID 84600396.

- ^ "Langmuir, Irving", in Webster's Biographical Dictionary (1943), Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-19-532134-0.

- ASIN B0007EIFMOASIN states author is Albert Rosenfeld; does not name an editor or state a volume.

- S2CID 124517477

- ^ "Langmuir, Irving, 1881-1957". history.aip.org. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ Suits, C. Guy; Martin, Miles J. (1974). "Irving Langmuir 1881—1957" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Coffey 2008, pp. 64–70

- .

- S2CID 4259549.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-12-349701-7.

- PMID 16587379.

- .

- ^ Coffey 2008, pp. 128–131

- ^ "Irving Langmuir". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- .

- ^ Staff writers (August 17, 1957). "Dr. Irving Langmuir Dies at 76; Winner of Nobel Chemistry Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Albert Rosenfeld (1961). The Quintessence of Irving Langmuir. Pergamon Press. p. 150.

Though Marion herself was not an assiduous churchgoer and had no serious objection to Irving's agnostic views, her grandfather had been an Episcopalian clergyman.

- ISSN 0027-8378.

- ^ Bernard Vonnegut, 82, Physicist Who Coaxed Rain From the Sky, NY Times, April 27, 1997.

- ^ Jeff Glorfeld (June 9, 2019). "The genius who ended up in a Vonnegut novel". Cosmos. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Sam Kean (September 5, 2017). "The Chemist Who Thought He Could Harness Hurricanes. Irving Langmuir's ill-fated attempts at seeding hurricane King showed just how difficult it is to control the weather". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter L" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Irving Langmuir". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ "SCI Perkin Medal". Science History Institute. May 31, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ "John J. Carty Award for the Advancement of Science". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

<ref></Serendipity in Science: Twenty Years at Langmuir University An Autobiography by Vincent J Schaefer, ScD; Compiled and Edited Don Rittner 2013 Circle Square Press, Voorheesville, NY <ref>

External links

- Works by or about Irving Langmuir at Internet Archive

- Langmuir Journal ACS Chemistry Journal of Surfaces and Colloids

- "Langmuir, Irving" Infoplease.com.

- " Irving Langmuir's Ball Lightning Tube". Ball Lightning Page. Science Hobbyist.

- "Irving Langmuir shows Whitney one of his inventions, the Pliotron tube. ca. 1920.". Willis Rodney Whitney: the "Father of basic research in industry".

- "Pathological Science" – noted lecture of December 18, 1953, at GE Labs

- "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules" JACS, Vol. 41, No. 6, 868.

- "The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum" JACS, Vol. 40, No. 9, 1361.

- "Irving Langmuir a great physical Chemist"; Resonance, July 2008

- Key Participants: Irving Langmuir – Linus Pauling and the Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

- Irving Langmuir on Nobelprize.org