Islam in Palestine

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

In the 7th century, the Arab

History

Early Islamization

Islam was first brought to the region of Palestine during the Early Muslim conquests of the 7th century, when the Rashidun Caliphate under the leadership of ʿUmar ibn al-Khattāb conquered the Shaam[a] region from the Byzantine Empire.[15]

The Muslim army conquered Jerusalem, held by the Byzantine Romans, in November, 636. For four months

Having accepted the surrender, Caliph Umar then entered Jerusalem with Sophronius "and courteously discoursed with the patriarch concerning its religious antiquities". When the hour for his prayer came, Umar was in the Anastasis, but refused to pray there, lest in the future the Muslims should use that as an excuse to break the treaty and confiscate the church. The Mosque of Omar, opposite the doors of the Anastasis, with the tall minaret, is known as the place to which he retired for his prayer.

According to the historian James Parkes, during the first century after the Muslim conquest (640–740), the caliph and governors of Syria and the Holy Land ruled entirely over Christian and Jewish subjects. He further states that apart from the Bedouin in the earliest days, the only Arabs west of the Jordan were the garrisons.[20]

Bishop Arculf, whose account of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the 7th century, De Locis Sanctis, written down by the monk Adamnan, described reasonably pleasant living conditions of Christians in Palestine in the first period of Muslim rule.[

Islamization under Abbasids and Fatimids

Some scholars believe that Islam became the majority religion in Palestine in the 9th century, with acculturation of the locals into

Rival dynasties and revolutions led to the eventual disunion of the Muslim world. During the 9th century, Palestine was conquered by the Fatimid dynasty, centered in Egypt. During that time the region of Palestine became again the center of violent disputes followed by wars, since enemies of the Fatimid dynasty attempted to conquer the region. At that time, the Byzantine Empire continued trying to recapture the territories they previously lost to the Muslims, including Jerusalem.

During the Fatimid era, the cities of Jerusalem and Hebron became prime destinations for Sufi wayfarers.[24] The creation of locally rooted Sufi-inspired communities and institutions between 1000 and 1250 were part and parcel of the conversion to Islam.[24]

The sixth Fatimid caliph, Caliph Al-Hakim (996–1021), who was believed to be "God made manifest" by the Druze, destroyed the Holy Sepulchre in 1009. This powerful provocation started the near 90-year preparation towards the First Crusade.[25]

The Samaritan community dropped in numbers during the various periods of Muslim rule in the region. The Samaritans could not rely on foreign assistance as much as the Christians did, nor on a large number of diaspora immigrants as did the Jews. The once-flourishing community declined over time, either through emigration or conversion to Islam among those who remained.[26] According to Milka Levy-Rubin, many Samaritans converted under Abbasid and Tulunid rule.[26]

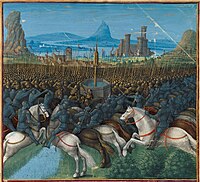

Early Crusades

In 1099, the Christian

Ayyubid rule and Late Crusades

In 1187, the

The Christian defeat led to a

Mamluk domination

In 1250, the Ayyubid Egyptian dynasty was overthrown by slave ("Mamluk") regiments, and a new dynasty - the

In 1291, the forces of the

The Mamluks were to rule Palestine for the following two centuries (1291–1516). The Muslim population became the majority, and many Muslim shrines were built such as

The Mamluks, ruling from Damascus, brought some prosperity to the area, particularly to Jerusalem, with an extensive programme involving the building of schools, hospices for pilgrims, the construction of Islamic colleges and the renovation of mosques. Mujir al-Din's extensive writing about 15th century Jerusalem documents the consolidation and expansion of Islamic sites in the Mamluk era.[34]

The ascendency of the

Rise of the Ottomans

On August 24, 1516, at the Battle of Marj Dabiq, the Ottoman Empire forces defeated the Mamluk sultanate forces and thus the Ottomans became the new rulers of the Levant. On October 28, they defeated the Mamluk forces once more in the Battle of Yaunis Khan and they annexed the region of Palestine. By December of that year the entire region of Palestine was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed] As a result of the Ottoman advance during the reign of Selim I,[38] the Sunni Ottoman Turks occupied the historic region of Palestine. Their leadership reinforced and ensured the centrality and importance of Islam as the dominant religion in the region. Swamps with the risk of malaria made it difficult to settle and farm on the coastal plains and in the valleys throughout most of the Ottoman era.[39]

In 1834,

In 1860, the Mosque of Omar was built in the Christian city of Bethlehem. It is the only mosque in Bethlehem's old city.[41]

Islam during British rule

In 1917, at the end of the

The gradual increase in the number of Jews in Palestine led to the development of a proto-

The

1948–1967: Islam under Israeli, Jordanian and Egyptian rule

On May 14, 1948, one day before the end of the

The British transferred the symbolic Islamic governance of the land to the

After the conquest of the Temple Mount during the Six-Day War, the Chief Israeli Rabbinate announced that Jewish people are forbidden of entering the Temple Mount. Since 1967, Israel controls the security on the Temple Mount, but the Muslim Waqf controls administrative matters, taking responsibility for the conduct of Islamic affairs just as it did during the Jordanian rule.[46][47]

Views

According to Erlich, Palestine's Islamization was mainly a result of urbanization and de-urbanization processes in Palestine under Muslim rule. During the Byzantine period, Palestine boasted more than thirty cities, or settlements with a bishop's see. Most of these cities declined under Muslim rule, and eventually disappeared; some of these became villages or townships, others were completely destroyed. This resulted in many cases in a weakening or complete disappearance of the local ecclesiastical administration. Over time, most of the local population converted to Islam. During this period, only Nablus and Jerusalem maintained their urban status, which is why, according to Erlich, religious minorities (Samaritans and Christians, respectively) survived there.[8]

Demographics

Islam

Today, Islam is a prominent religion in both Gaza and the West Bank. Most of the population in the State of Palestine are Muslims (85% in the West Bank and 99% in the Gaza Strip).[48][49]

Sunni Islam

Sunnis constitute 85% of Palestinian Muslims,[50] of which the predominant madhab is Hanafi, which is one of the four schools of Islamic law in Sunni Islam. Salafism took root in Gaza in the 1970s, when Palestinian students returned from studying abroad at religious schools in Saudi Arabia. A number of Salafi groups in Gaza continue to receive support and funding from Riyadh.[51]

Shia Islam

From 1923 to 1948, there were seven villages in

Since 1979, due to Iran's influence, some Palestinian Sunnis have converted to Shia Islam. Israeli

Non-denominational Islam

According to the Pew Research Center, non-denominational Muslims constitute 15% of the Palestinian Muslim population.[50]

See also

- Muslim conquest of the Levant

- Islam in Israel

- Palestinian nationalism

- Time periods in the Palestine region

- Islamization

- History of Israel

- History of Palestine

- Palestinian Christians

- Spread of Islam

- Muslim conquests

- Islamization of Jerusalem

- Islamization of East Jerusalem under Jordanian rule

- Islamization of the Temple Mount

- Islamization of Gaza

Notes

- Arabic: اَلـشَّـام) is a region that is bordered by the Taurus Mountains of Anatolia in the north, the Mediterranean Sea in the west, the Arabian Desert in the south, and Mesopotamia in the east.[12] It includes the modern countries of Syria and Lebanon, and the land of Palestine.[13][14]

References

- ^ West Bank. CIA Factbook

- ^ Gaza Strip. CIA Factbook

- )

- ^ JSTOR 3632444.

- OCLC 958547332.

From the data given above it can be concluded that the Muslim population of Central Samaria, during the early Muslim period, was not an autochthonous population which had converted to Christianity. They arrived there either by way of migration or as a result of a process of sedentarization of the nomads who had filled the vacuum created by the departing Samaritans at the end of the Byzantine period [...] To sum up: in the only rural region in Palestine in which, according to all the written and archeological sources, the process of Islamization was completed already in the twelfth century, there occurred events consistent with the model propounded by Levtzion and Vryonis: the region was abandoned by its original sedentary population and the subsequent vacuum was apparently filled by nomads who, at a later stage, gradually became sedentarized

- ^ Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages; Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–900, Oxford University press 2005. p. 130. "In Syria and Palestine, where there were already Arabs before the conquest, settlement was also permitted in the old urban centres and elsewhere, presumably privileging the political centres of the provinces."

- ^ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, Oxford University Press 2014 pp.312–324, 329 (theory of imported population unsubstantiated);.

- ^ OCLC 1310046222.

- ^ Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, (1988) Cambridge University Press 3rd.ed.2014 p.156

- ^ .

- ^ Ira M. Lapidus, Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 201.

- ISBN 978-0-19-921297-2.

The western coastline and the eastern deserts set the boundaries for the Levant ... The Euphrates and the area around Jebel el-Bishrī mark the eastern boundary of the northern Levant, as does the Syrian Desert beyond the Anti-Lebanon range's eastern hinterland and Mount Hermon. This boundary continues south in the form of the highlands and eastern desert regions of Transjordan.

- C.E. Bosworth, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 9 (1997), page 261.

- MuslimArabic usage.

- ^ A Concise History of Islam and the Arabs MidEastWeb.org

- ^ "Jerusalem". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1910.

- ISBN 0-87820-217-X.

- ^ From the article on Islam in Palestine and Israel in Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- ^ Mustafa Abu Sway, The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source (PDF), Central Conference of American Rabbis, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28

- ^ James Parkes, Whose Land? A History of the Peoples of Palestine (Penguin books, 1970), p. 66

- OCLC 1105497638.

- from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ISBN 9783525535738.

- ^ ISBN 9780674032019.

- ^ Charles Mills (June 1820). "Mill's History of the Crusades". The Eclectic Review. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ OCLC 1310046222.

- ^ Esposito, John L., ed. The Islamic World: Past and Present The Islamic World:Past and Present 3-Volume Set: Past and Present 3-Volume Set.] Google Books. 2 February 2013.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim. Islamic Imperialism: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. p. 73

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard. The Politics of Holiness in Jerusalem. 21 September 2001. 2 February 2013.

- ^ Siddique, Tahsin. "Locating Jerusalem in Theology and Practice During the Crusades." Archived 2014-09-01 at the Wayback Machine University of California, Santa Cruz History. 21 March 2009. 2 February 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-8476-9430-3

- ^ "Battle of Ḥaṭṭīn." Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 February 2013.

- ^ Fromherz, Allan James. Ibn Khaldun: Life and Times. Google Books. 4 February 2013.

- JSTOR 604667.

- ^ Laura Etheredge, Historic Palestine, Israel, and the Emerging Palestinian Autonomous Areas, The Rosen Publishing Group 2011 p.43.

- ^ Michael Avi-Yonah, A History of Israel and the Holy Land, A&C Black, 2003 pp.279–282.

- ^ Richard G. Neuhauser, 'Jerusalem,' in John Block Friedman, Kristen Mossler Figg (eds.),Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia, Routledge 2013 pp.300–302, p.302

- Parkes, James (1970) [1949]. "Turkish Territorial Divisions in 1914". Whose Land?: A History of the Peoples of Palestine. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 187. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Ruth Kark and Noam Levin, "The Environment in Palestine in the Late Ottoman period, 1798-1918," in Daniel E. Orenstein, Alon Tal, Char Miller (eds.),Between Ruin and Restoration: An Environmental History of Israel University of Pittsburgh 2012 pp.1–28 p.11.

- ^ Alex Carmel "A Note on the Christian Contribution to the Development of Palestine in the 19th century," in David Kushner (ed.) Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period: Political, Social, and Economic Transformation, BRILL, 1986 pp.303–304.

- ^ Mosque of Omar (Bethlehem) Archived July 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Atlas Travels and Tourism Agency.

- ^ "al-Husseini, Hajj (Muhammad) Amin." The Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East. Ed. Avraham Sela. New York: Continuum, 2002. pp. 360–362.

- ^ Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab Israeli Conflict: A History With Documents. Bedford/St. Martin’s: Boston. (2004). Pg. 198

- ^ GENERAL PROGRESS REPORT AND SUPPLEMENTARY REPORT OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION COMMISSION FOR PALESTINE, Covering the period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950, GA A/1367/Rev.1 23 October 1950

- ^ Morris, Benny. "Yosef Weitz and the Transfer Committees 1948–49" JSTOR: Middle Eastern Studies vol. 22, no. 4 (Oct., 1986), p. 522.

- ^ Sela. "Jerusalem." The Continuum Political Encyclopedia. Sela. pp. 491–498.

- ^ "The History of Palestine" (PDF).

- ^ "The World Factbook." CIA. 19 December 2015. West Bank

- ^ "The World Factbook." CIA. 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Religious Identity Among Muslims". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2012-08-09. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- ^ Kaufman (2006). The 1922 census also listed the Muslim minority in al-Bassa as Shia, but Kaufman determined they were actually Sunni.

- ^ Census of Palestine 1931; Palestine Part I, Report. Vol. 1. Alexandria. 1933. p. 82.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Hamas brutally assaults Shi'ite worshippers in Gaza". Haaretz. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Al-Sabireen: an Iran-Backed Palestinian Movement in the Style of Hezbollah". رصيف 22. 2018-03-14. Retrieved 2020-07-06.