Italian economic miracle

The Italian economic miracle or Italian economic boom (Italian: il miracolo economico italiano or il boom economico italiano) is the term used by historians, economists, and the mass media[1] to designate the prolonged period of strong economic growth in Italy after World War II to the late 1960s, and in particular the years from 1958 to 1963.[2] This phase of Italian history represented not only a cornerstone in the economic and social development of the country—which was transformed from a poor, mainly rural, nation into a global industrial power—but also a period of momentous change in Italian society and culture.[3] As summed up by one historian, by the end of the 1970s, "social security coverage had been made comprehensive and relatively generous. The material standard of living had vastly improved for the great majority of the population."[4]

History

After the end of

The above-mentioned highly favorable historical backgrounds, combined with the presence of a large and cheap stock of labour force, laid the foundations of a spectacular economic growth. The boom lasted almost uninterrupted until the "

Society and culture

The impact of the economic miracle on Italian society was huge. Fast economic expansion induced massive inflows of migrants from rural Southern Italy to the industrial cities of the North. Emigration was especially directed to the factories of the so-called "industrial triangle", the region placed between the major manufacturing centres of Milan and Turin and the seaport of Genoa. Between 1955 and 1971, around 9 million people are estimated to have been involved in inter-regional migrations in Italy, uprooting entire communities and creating large metropolitan areas.[11]

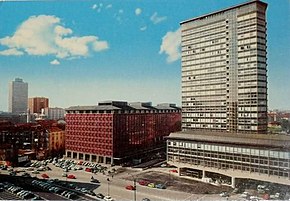

The needs of a modernizing economy and society created a great demand for new transport and energy infrastructures. Thousands of miles of railways and highways were completed in record times to connect the main urban areas, while dams and power plants were built all over Italy, often without regard for geological and environmental conditions. A concurrent boom of the real estate market, increasingly under pressure by strong demographic growth and internal migrations, led to the explosion of urban areas. Vast neighborhoods of low-income apartments and

At the same time, the doubling of Italian GDP between 1950 and 1962

Criticism

The pervasive influence of the

See also

- Economic history of Italy

- Economic miracle

- Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale

- Japanese economic miracle

- La Dolce Vita(1960)

- Post–World War II economic expansion

- Spanish miracle

- Wirtschaftswunder

- Years of Lead, the period of unrest following the Italian economic miracle

References

- ^ Life, November 24, 1967 (p.48)

- ISBN 0-521-49627-6.

- ISBN 978-0-253-21948-0.

- ^ Italy, a difficult democracy: a survey of Italian politics by Frederic Spotts and Theodor Wieser

- ISBN 0-521-37840-0.

- ISBN 0-521-49627-6.

- ISBN 3-11-012158-1.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (July 1, 1963). Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. (eds.). "290 - Remarks at a Dinner Given in His Honor by President Segni". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ Tagliabue, John (11 August 2007). "Italian Pride Is Revived in a Tiny Fiat". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Cappellieri, Alba. "Brionvega. A brief history of the black box". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ISBN 1-4039-6153-0.

- ISBN 0521846633.

- ^ Poverty and Inequality in Common Market Countries edited by Victor George and Roger Lawson

Further reading

- Nardozzi, Giangiacomo. "The Italian" Economic Miracle"." Rivista di storia economica (2003) 19#2 pp: 139-180, in English

- Rota, Mauro. "Credit and growth: reconsidering Italian industrial policy during the Golden Age." European Review of Economic History (2013) 17#4 pp: 431–451.

- Tolliday, Steven W. "Introduction: enterprise and state in the Italian'economic miracle'." Enterprise and Society (2000) 1#2 pp: 241–248.