Italian Empire

Italian Empire Impero italiano (Italian) | |

|---|---|

| 1882–1947 | |

|

Flag | |

Kingdom of Italy Colonies of Italy

Protectorates and areas occupied during World War II | |

| Status | Victor Emmanuel III |

• 1946 | Umberto II |

| History | |

• Empire formally relinquished | 1947 |

| 1950–1960 | |

| Area | |

| 1938[1] | 3,798,000 km2 (1,466,000 sq mi) |

| 1941[2] | 3,824,879 km2 (1,476,794 sq mi) |

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

The Italian colonial empire (

In early 1940 it was the third greatest empire in the world (after the British and the French) for extention & population.

The Fascist government that came to power under the leadership of the dictator

During World War II, Italy allied itself with Nazi Germany in 1940 and it also occupied British Somaliland, western Egypt, much of Yugoslavia, Tunisia, parts of south-eastern France and most of Greece; however, it then lost those conquests and its African colonies to the invading Allied forces by 1943. In 1947, Italy officially relinquished claims on its former colonies. In 1950, former Italian Somaliland, then under British administration, was turned into the Trust Territory of Somaliland until it became independent in 1960.

History

Background and pre-unification era

Imperialism in Italy dates back to

Scramble for an empire

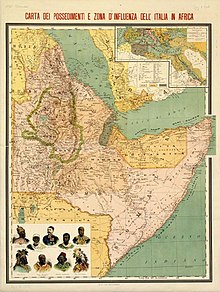

Once unified as a nation-state in the late 19th century, Italy intended to compete with the other European powers for the new age of European colonial expansion. It saw its interests in the Mediterranean and in the

While attempts were made to buy the Nicobar Islands from Denmark in 1864 and 1865,[14] the genesis of the Italian colonial empire was the purchase in 1869 of Assab Bay on the Red Sea by an Italian navigation company which intended to establish a coaling station at the time the Suez Canal was being opened to navigation.[15] This was taken over by the Italian government in 1882, becoming modern Italy's first overseas territory.[16]

Italy's search for colonies continued until February 1886, when, by secret agreement with Britain, it annexed the port of

Italy also fought in the

In 1898, in the wake of the acquisition of

The concession was administered by the Italian consul in Tianjin.

A wave of nationalism that swept Italy at the turn of the 20th century led to the founding of the Italian Nationalist Association, which pressed for the expansion of Italy's empire. Newspapers were filled with talk of revenge for the humiliations suffered in Ethiopia at the end of the previous century, and of nostalgia for the Roman era.

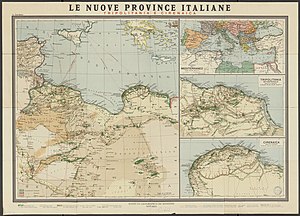

Libya, it was suggested, as an ex-Roman colony, should be "taken back" to provide a solution to the problems of Southern Italy's population growth. Fearful of being excluded altogether from North Africa by Britain and France, and mindful of public opinion, Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti ordered the declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire, of which Libya was part, in October 1911.[27]

As a result of the Italo-Turkish War, Italy gained Libya and the Dodecanese Islands from the Ottoman Empire.

The 1912 Libya desert war featured the first use of an armoured fighting vehicle in military history and marked the first significant employment of air power in warfare.[28][b]

World War I and aftermath

In 1914 Italy remained neutral and did not join its ally Germany in World War I. The Allies made promises and in 1915 Italy joined them. It was promised territorial spoils mainly from Austria and Turkey.[29]

Prior to direct intervention in World War I, Italy occupied the Albanian port of

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. The Treaty of London guaranteed Italy the right to annex a large portion of Dalmatia in exchange for Italy's participation on the Allied side. From 5–6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Lissa, Lagosta, Sebenico, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast.[30] By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the Treaty of London and by 17 November had seized Fiume as well.[31] In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia.[31] Famous Italian nationalist Gabriele D'Annunzio supported the seizure of Dalmatia, and proceeded to Zara (today's Zadar) in an Italian warship in December 1918.[32]

At the concluding Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Italy received less in Europe than had been promised and none overseas mandate except for a promise of colonial compensations made on 7 May 1919 during the partition of Germany's colonies between France and Britain. To satisfy this promise, France and Britain directly or indirectly gave Italy, from 1919 to 1935, a number of territories to expand Libya (Cufra, Sarra, Giarabub, the Aouzou strip, other lands in the Sahara), Somalia (Jubaland), the Dodecanese (Kastellorizo), and Eritrea (Raheita, the Hanish islands). In April 1920, it was agreed between the British and Italian foreign ministers that Jubaland would be Italy's first compensation from Britain, but London held back on the deal for several years, aiming to use it as leverage to force Italy to cede the Dodecanese to Greece.[33]

Fascism and the Italian Empire

Legend:

In 1922, the leader of the

The month following the ratification of the Lausanne treaty, Mussolini ordered the invasion of the Greek island of

During the late 1920s, imperial expansion became an increasingly favoured theme in Mussolini's speeches.[35] Amongst Mussolini's aims were that Italy had to become the dominant power in the Mediterranean that would be able to challenge France or Britain, as well as attain access to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.[35] Mussolini alleged that Italy required uncontested access to the world's oceans and shipping lanes to ensure its national sovereignty.[36] This was elaborated on in a document he later drew up in 1939 called "The March to the Oceans", and included in the official records of a meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism.[36] This text asserted that maritime position determined a nation's independence: countries with free access to the high seas were independent; while those who lacked this, were not. Italy, which only had access to an inland sea without French and British acquiescence, was only a "semi-independent nation", and alleged to be a "prisoner in the Mediterranean":[36]

The bars of this prison are Corsica, Tunisia, Malta, and Cyprus. The guards of this prison are Gibraltar and Suez. Corsica is a pistol pointed at the heart of Italy; Tunisia at Sicily. Malta and Cyprus constitute a threat to all our positions in the eastern and western Mediterranean. Greece, Turkey, and Egypt have been ready to form a chain with Great Britain and to complete the politico-military encirclement of Italy. Thus Greece, Turkey, and Egypt must be considered vital enemies of Italy's expansion ... The aim of Italian policy, which cannot have, and does not have continental objectives of a European territorial nature except Albania, is first of all to break the bars of this prison ... Once the bars are broken, Italian policy can only have one motto – to march to the oceans.

— Benito Mussolini, The March to the Oceans[36]

In the Balkans, the Fascist regime claimed Dalmatia and held ambitions over Albania, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Vardar Macedonia, and Greece based on the precedent of previous Roman dominance in these regions.[37] Dalmatia and Slovenia were to be directly annexed into Italy while the remainder of the Balkans was to be transformed into Italian client states.[38] The regime also sought to establish protective patron-client relationships with Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Bulgaria.[37]

In both 1932 and 1935, Italy demanded a League of Nations mandate of the former German Cameroon and a free hand in Ethiopia from France in return for Italian support against Germany (see Stresa Front).[39] This was refused by French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot, who was not yet sufficiently worried about the prospect of a German resurgence.[39]

In its

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War cost Italy 4,359 killed in action—2,313 Italians, 1,086 Eritreans, 507 Somalis and Libyans, and 453 Italian laborers.

In July 1936, Francisco Franco of the Nationalist faction in the Spanish Civil War requested Italian support against the ruling Republican faction, and guaranteed that, if Italy supported the Nationalists, "future relations would be more than friendly" and that Italian support "would have permitted the influence of Rome to prevail over that of Berlin in the future politics of Spain".[42] Italy intervened in the civil war with the intention of occupying the Balearic Islands and creating a client state in Spain.[43] Italy sought the control of the Balearic Islands due to its strategic position – Italy could use the islands as a base to disrupt the lines of communication between France and its North African colonies and between British Gibraltar and Malta.[44] After the victory by Franco and the Nationalists in the war, Italy pressured Franco to permit an Italian occupation of the Balearic Islands but he did not do so.[45]

After the United Kingdom signed the Anglo-Italian

In 1939, Italy

World War II

Mussolini entered World War II in June 1940 on the side of Adolf Hitler with plans to enlarge Italy's territorial holdings. He had designs on an area of western Yugoslavia, southern France, Corsica, Malta, Tunisia, part of Algeria, an Atlantic port in Morocco, French Somaliland and British-controlled Egypt and Sudan.[50]

On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on Britain and France; both countries had been at war with

In October 1940, Mussolini ordered the

During the height of the

The

In November 1942, when the Germans occupied

End of the empire

By the autumn of 1943, the Italian Empire and all

After 25 July, the new Italian government under the King and Field Marshal

In 1947, the

Former colonies, protectorates and occupied areas

- Italian Eritrea (1882–1947)

- Italian Somalia(1889–1947)

- Trust Territory of Somaliland (1950–1960)

- Libya (1911–1947)

- Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica (1911–1934)

- Italian Libya (1934–1943)

- Italian East Africa (1936–1941)

- Italian Ethiopia (1936–1941)

- Italian concessions in China

- Italian concession of Tientsin(1901–1943)

- Italian Albania (1917–1920, 1939–1943)

- Italian Islands of the Aegean (1912–1947)

- Italian occupation of France (1940–1943)

- Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945)

- Italian occupation of Montenegro(1941–1943)

- Hellenic State (1941–1943)

- Tunisia (1942–1943)

Notes

- ^ Total Italian, Eritrean, and Somali deaths, including those from disease, were estimated at 9,000.[23]

- Ottoman Army cavalry during a battle at Zanzur in the Italo-Turkish War, making an important contribution to the Italian Army's offense in this battle. History's first war death of a pilot occurred when an aircraft crashed during a recon sortie.[28]

References

- ISBN 9780521785037. Archivedfrom the original on 16 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Soldaten-Atlas (Tornisterschrift des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, Heft 39). Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut. 1941. p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nigel Thomas. Armies in the Balkans 1914–18. Osprey Publishing, 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Chapin Metz, Helen, ed., Libya: A Country Study. Chapter XIX.

- ^ Istat (December 2010). "I censimenti nell'Italia unita I censimenti nell'Italia unita Le fonti di stato della popolazione tra il XIX e il XXI secolo ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI STATISTICA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI DEMOGRAFIA STORICA Le fonti di stato della popolazione tra il XIX e il XXI secolo" (PDF). Annali di Statistica. XII. 2: 263. Archived from the original(PDF) on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Libya - History, People, & Government". Britannica.com. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Betts (1975), p.12

- ISBN 978-0-7766-0559-3.

- ISBN 9780404170097.

- ^ Betts (1975), p.97

- ^ Lowe, p.21

- ^ Lowe, p.24

- ^ Lowe, p.27

- ^ Storia Militare della Colonia Eritrea, Vol. I. Roma: Ministero della Guerra. 1935. pp. 15–16.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Mia Fuller, "Italian Colonial Rule", Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ Theodore M. Vestal, "Reflections on the Battle of Adwa and Its Significance for Today", in The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism (Algora, 2005), p. 22.

- ^ Pakenham (1992), p.280

- ^ Pakenham, p.281

- ^ Killinger (2002), p.122

- ^ Pakenham, p.470

- ^ Killinger, p.122

- ^ Pakenham (1992), p.7

- ^ a b c d Clodfelter 2017, p. 202.

- ISBN 9780283978623.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Italy’s Encounters with Modern China: Imperial Dreams, Strategic Ambitions, edited by Maurizio Marinelli and Giovanni Andornino, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014

- ^ Maurizio Marinelli, Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror: Colonial Italy Reflects on Tianjin [1]

- ^ Killinger (2002), p.133

- ^ a b c Clodfelter 2017, p. 353.

- ^ Renzi, 1968.

- ^ Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo. History of Dalmatia. Giardini, 1993. Pp. 281.

- ^ a b Paul O'Brien. Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17.

- ^ A. Rossi. The Rise of Italian Fascism: 1918–1922. New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2010. Pp. 47.

- ^ Lowe, p.187

- ^ Lowe, pp. 191–199

- ^ a b c Smith, Dennis Mack (1981). Mussolini, p. 170. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London.

- ^ a b c d Salerno, Reynolds Mathewson (2002). Vital crossroads: Mediterranean origins of the Second World War, 1935–1940, pp. 105–106. Cornell University Press

- ^ a b Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries. A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 1998. Pp. 467.

- ^ Allan R. Millett, Williamson Murray. Military Effectiveness, Volume 2. New edition. New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2010. P. 184.

- ^ a b Burgwyn, James H. (1997). Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940, p. 68. Praeger Publishers.

- ^ Guida dell'Africa Orientale Italiana (in Italian). Milano: CTI. 1938. p. 33.

- ^ a b Clodfelter 2017, p. 355.

- ^ Sebastian Balfour, Paul Preston. Spain and the Great Powers in the Twentieth Century. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 1999. P. 152.

- ^ R. J. B. Bosworth. The Oxford handbook of fascism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009. Pp. 246.

- ^ John J. Mearsheimer. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W. W. Norton & Company, 2003.

- ^ The Road to Oran: Anglo-French Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. Pp. 24.

- ^ a b Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935–1940. Cornell University, 2002. p 82–83.

- ^ a b "French Army breaks a one-day strike and stands on guard against a land-hungry Italy", LIFE, 19 Dec 1938. Pp. 23.

- ^ a b Dickson (2001), pg. 69

- ^ Time Magazine Aosta on Alag?

- ^ Calvocoressi (1999) p.166

- ^ a b Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings. New York, New York, USA: Enigma Books, 2008. Pp. 132.

- ^ Dickson (2001) p.100

- ^ Dickson (2001) p.101

- ^ Italian Map showing with green lines the territories conquered in 1940 by the Italians in Sudan and Kenya. British and French somaliland are shown in white, as part of the A.O.I. (Africa Orientale Italiana)

- ^ Dickson (2001) p.103

- ^ Jowett (2001) p.7

Bibliography

- Andall, Jacqueline and Derek Duncan, eds. (2005). Italian Colonialism: Legacy and Memory.

- Ben-Ghiat, Ruth and Mia Fuller, eds. (2005). Italian Colonialism.

- Betts, Raymond (1975). The False Dawn: European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century. University of Minnesota. ISBN 9780816607624.

- Barker, A. J. (1971). The Rape of Ethiopia. Ballantine Books.

- Bosworth, R. J. B. (2005). Mussolini's Italy: Life Under the Fascist Dictatorship, 1915–1945. Penguin Books. ISBN 9781594200786.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Dickson, Keith (2001). World War II For Dummies. Wiley Publishing, INC. ISBN 9780764553523.

- Finaldi, Giuseppe (2016). A History of Italian Colonialism, 1860–1907: Europe’s Last Empire (Taylor & Francis).

- Hofmann, Reto (2015). The Fascist Effect: Japan and Italy, 1915–1952 (Cornell UP) online</ref>

- Jowett, Philip (1995). Axis Forces in Yugoslavia 1941–45. Osprey Publishing.

- Jowett, Philip (2001). The Italian Army 1940–45 (2): Africa 1940–43. Osprey Publishing.

- Kelly, Saul (2000). "Britain, the United States, and the end of the Italian empire in Africa, 1940–52." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 28.3: 51–70.

- Kelly, Saul (2000). Cold War in the Desert: Britain, the United States & the Italian Colonies, 1945–52.

- Killinger, Charles (2002). The History of Italy. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313314834.

- Lowe, C.J. (2002). Italian Foreign Policy 1870–1940. Routledge.

- McGuire, Valerie (2020). Italy's Sea: Empire and Nation in the Mediterranean, 1895–1945 (Liverpool University Press).

- Marinelli, Maurizio and Giovanni Andornino (2014). Italy's Encounter with Modern China: Imperial dreams, strategic ambitions, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. New York: Perennial. ISBN 9780380719990.

- Palumbo, Patrizia (2003). Place in the Sun: Africa in Italian Colonial Culture from Post-Unification to the Present, since 1860.

- Peretti, Luca (2024). "Built to last? Material legacies of Italian colonialism. Interviews with Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Alessandra Ferrini, Viviana Gravano, Hannes Obermair, Resistenze in Cirenaica, Igiaba Scego, and Colletivo Tezeta". Interventions. International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. Taylor & Francis: 1–17. .

- Pergher, Roberta (2017). Mussolini's Nation-Empire: Sovereignty and Settlement in Italy's Borderlands, 1922–1943 (Cambridge UP).

- Poddar, Prem, and Lars Jensen, eds. (2008). A historical companion to postcolonial literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires (Edinburgh UP), "Italy and its colonies" pp 262–313. excerpt

- Renzi, William A. (1968). "Italy's neutrality and entrance into the Great War: a re-examination." American Historical Review 73.5: 1414–32. online

- Shinn, Christopher A. (2016). "Inside the Italian Empire: Colonial Africa, Race Wars, and the ‘Southern Question’", in Shades of Whiteness (Brill), pp. 35–51.

- Srivastava, Neelam (2018). Italian Colonialism and Resistances to Empire, 1930–1970 (Palgrave Macmillan).

- Steinmetz, George (2018). "Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s Italian Fascism’s Empire Cinema." American Journal of Cultural Sociology 6.1: 212–22 online.

- Tripodi, Paolo (1999). Colonial Legacy in Somalia: Rome & Mogadishu from Colonial Administration to Operation Restore Hope, covers 19th century to 1999.

- Wright, Patricia (1973). "Italy's African Dream: Part I, The Adowa Nightmare". History Today (Mar), Vol. 23, Issue 3, pp. 153–60, online:

- "Italy's African Dream. Part 2: Fatal Victory, 1935–6." History Today (April 1973), Vol. 23, Issue 4, pp. 256–65.

- "Italy's African Dream. Part 3: Nemesis in 1941," History Today (May 1973), Vol. 23, Issue 5, pp. 336–34.

External links

- (in Italian) Atlas of Italian colonies, written by Baratta Mario and Visintin Luigi in 1928

- Simona Berhe: Colonies (Italy), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.