Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the

Classification

The Italics were an ethnolinguistic group who are identified by their use of the Italic languages, which form one of the branches of Indo-European languages.

Outside of the specialised linguistic literature, the term is also used to describe the

History

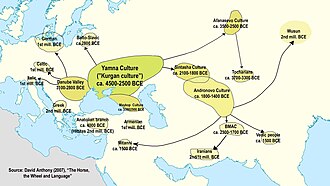

Copper Age

During the Copper Age, at the same time that metalworking appeared, Indo-European speaking peoples are believed to have migrated to Italy in several waves.[4] Associated with this migration are the Remedello culture and Rinaldone culture in Northern and Central Italy, and the Gaudo culture of Southern Italy. These cultures were led by a warrior-aristocracy and are considered intrusive.[4] Their Indo-European character is suggested by the presence of weapons in burials, the appearance of the horse in Italy at this time and material similarities with cultures of Central Europe.[4]

Early and Middle Bronze Age

According to

From the late third to the early second millennium BC, tribes coming both from the north and from Franco-Iberia brought the

In the mid-second millennium BCE, the

Late Bronze Age

The

The

In the 13th century BC, Proto-

Iron Age

In the early Iron Age, the relatively homogeneous Proto-Villanovan culture (1200-900 BC), closely associated with the Celtic Hallstatt culture of Alpine Austria, characterised by the introduction of iron-working and the practice of cremation coupled with the burial of ashes in distinctive pottery, shows a process of fragmentation and regionalisation. In Tuscany and in part of Emilia-Romagna, Latium and Campania, the Proto-Villanovan culture was followed by the Villanovan culture. The earliest remains of Villanovan culture date back to circa 900 BC.

In the region south of the Tiber (Latium Vetus), the Latial culture of the Latins emerged, while in the north-east of the peninsula the Este culture of the Veneti appeared. Roughly in the same period, from their core area in central Italy (modern-day Umbria and Sabina region), the Osco-Umbrians began to emigrate in various waves, through the process of Ver sacrum, the ritualized extension of colonies, in southern Latium, Molise and the whole southern half of the peninsula, replacing the previous tribes, such as the Opici and the Oenotrians. This corresponds with the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène.[23] The Umbrian necropolis of Terni, which dates back to the 10th century BC, was identical in every aspect to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca culture.[24]

Antiquity

By the mid-first millennium BC, the Latins of Rome were growing in power and influence. This led to the establishment of ancient Roman civilization. In order to combat the non-Italic Etruscans, several Italic tribes united in the Latin League. After the Latins had liberated themselves from Etruscan rule they acquired a dominant position among the Italic tribes. Frequent conflict between various Italic tribes followed. The best documented of these are the wars between the Latins and the Samnites.[2]

The Latins eventually succeeded in unifying the Italic elements in the country. Many non-Latin Italic tribes adopted Latin culture and acquired Roman citizenship. During this time Italic

In the subsequent centuries, Italic tribes were assimilated into Latin culture in a process known as Romanization.

Theatre

Italian peoples such as the

Even the Samnites had original representational forms that had a lot of influence on Roman dramaturgy such as the Atellan Farce comedies, and some architectural testimonies such as the theater of Pietrabbondante in Molise, and that of Nocera Superiore on which the Romans built their own.[26] The construction of the Samnite theaters of Pietrabbondante and Nocera make the architectural filiation of the Greek theater understood.

Genetics

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

A genetic study published in

See also

- List of ancient Italic peoples

- Romance-speaking world

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- Pan-Latinism

References

- ^ https://indo-european.eu/2019/11/r1b-rich-bell-beaker-derived-italic-peoples-from-the-west-vs-etruscans-from-the-east/

- ^ a b c d Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 452–459

- ^ "Ancient Italic people, Britannica".

- ^ a b c d e Mallory 1997, pp. 314–319

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 305

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 344

- ^ Hans, Wagner. "Anatolien war nicht Ur-Heimat der indogermanischen Stämme". eurasischesmagazin. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- PMID 21357231.

- ^ "A Grammar of Proto-Germanic, Winfred P. Lehmann Jonathan Slocum" (PDF).

- ISBN 0-521-84811-3

- ^ a b c Anthony 2007, p. 367

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- OCLC 663998477.

- OCLC 708337872.

- S2CID 160050623.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 620–658

- ^ "Le grandi avventure dell'archeologia (I misteri delle civiltà scomparse) - Libro Usato - Curcio - | IBS". www.ibs.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- ^ Soren, David; Martin, Archer (2015). Art and Archaeology of Ancient Rome. Midnight Marquee Press, Incorporated. p. 9.

- ^ M. Gimbutas Bronze Age Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe pp. 339–345

- ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9

- ^ G. Frigerio, Il territorio comasco dall'età della pietra alla fine dell'età del bronzo, in Como nell'antichità, Società Archeologica Comense, Como 1987.

- ^ Leonelli, Valentina. La necropoli delle Acciaierie di Terni: contributi per una edizione critica (Cestres ed.). p. 33.

- ^ Farinacci, Manlio. Carsulae svelata e Terni sotterranea. Associazione Culturale UMRU - Terni.

- ^ a b "Storia del teatro: lo spazio scenico in Toscana" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ "La fertile terra di Nuceria Alfaterna" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, Table 2 Sample Information, Rows 29-32, 36-37.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 3.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Antonio, Margaret L.; et al. (November 8, 2019). "Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean". PMID 31699931.

- ISBN 978-1598843026.

- Devoto, Giacomo; Buti, Gianna G. (1974). Preistoria e storia delle regioni d'Italia. Florence: Sansoni.

- Devoto, Giacomo (1951). Gli antichi Italici. Florence: Vallechi.

- GP (2001). MultiCultural Review: Dedicated to a Better Understanding of Ethnic, Racial, and Religious Diversity, Volume 10. GP Subscription Publications. ISBN 0823997006.

- ISBN 1884964982. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. ISBN 0313309841.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1998). Così nacque l'Italia: profili di popoli riscoperti. Turin: Società Editrice Internazionale.

- Pigorini, Luigi (1910). Gli abitanti primitivi dell'Italia. Rome: Bertero.

- ISBN 0880334401.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1999). Romanians and Romania: A Brief History. East European Monographs. ISBN 9735770377.

- ISBN 0880333456.

- ISBN 88-15-05708-0.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. ISBN 1438129181.

Further reading

- M. Aberson, R. Wachter, «Ombriens, Sabins, Picéniens, peuples sabelliques des Abruzzes : une enquête historique, épigraphique et linguistique", in : Entre archéologie et Histoire : dialogues sur divers peuples de l’Italie préromaine, Bern, etc., 2014, p. 167-201.