Jack Kirby

| Jack Kirby | |

|---|---|

Bill Finger Award | |

| Spouse(s) |

Rosalind Goldstein (m. 1942) |

| Children | 4 |

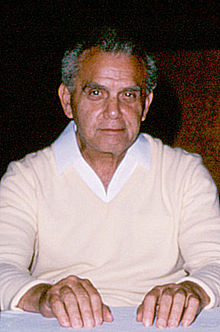

Jack Kirby

After serving in the

, among numerous others. Kirby's titles garnered high sales and critical acclaim, but in 1970, feeling he had been treated unfairly, largely in the realm of authorship credit and creators' rights, Kirby left the company for rival DC.At DC, Kirby created his

Kirby was married to Rosalind Goldstein in 1942. They had four children and remained married until his death from heart failure in 1994, at the age of 76. The

Early life (1917–1935)

Jack Kirby was born Jacob Kurtzberg on August 28, 1917, at 147

At age 14, Kirby enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, leaving after a week. "I wasn't the kind of student that Pratt was looking for. They wanted people who would work on something forever. I didn't want to work on any project forever. I intended to get things done".[10]

Career

Entry into comics (1936–1940)

Kirby joined the

Around that time, the American comic book industry was booming. Kirby began writing and drawing for the

Partnership with Joe Simon

Kirby moved on to comic-book publisher and newspaper syndicator

After leaving Fox and collaborating on the premiere issue of

With the success of the Captain America character, Simon said he felt that Goodman was not paying the pair the promised percentage of profits, and so sought work for the two of them at National Comics Publications (later renamed DC Comics).[20] Kirby and Simon negotiated a deal that would pay them a combined $500 a week, as opposed to the $75 and $85 they respectively earned at Timely.[24] The pair feared Goodman would not pay them if he found they were moving to National, but many people knew of their plan, including Timely editorial assistant Stan Lee. When Goodman eventually discovered it, he told Simon and Kirby to leave after finishing work on Captain America Comics #10.[25] Kirby was bitterly convinced it was specifically Lee who betrayed them, ignoring Simon's willingness to give him the benefit of the doubt.[26]

Kirby and Simon spent their first weeks at National trying to devise new characters while the company sought how best to utilize the pair.

World War II (1943–1945)

With World War II underway, Liebowitz expected that Simon and Kirby would be

Postwar career (1946–1955)

After the war, Simon arranged work for Kirby and himself at

The team found its greatest success in the postwar period by creating

Bitter that

After Simon (1956–1957)

At the urging of a Crestwood salesman, Kirby and Simon launched their own comics company,

At this point in the mid-1950s, Kirby made a temporary return to the former

But in 1957, distribution troubles caused the "Atlas implosion" that resulted in several series being dropped and no new material being assigned for many months. It would be the following year before Kirby returned to the nascent Marvel.For DC around this time, Kirby co-created with writers Dick and Dave Wood the non-superpowered adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown in Showcase #6 (Feb. 1957),[54] while contributing to such anthologies as House of Mystery.[14] During 30 months freelancing for DC, Kirby drew slightly more than 600 pages, which included 11 six-page Green Arrow stories in World's Finest Comics and Adventure Comics that, in a rarity, Kirby inked himself.[55] Kirby recast the archer as a science-fiction hero, moving him away from his Batman-formula roots, but, in the process, alienating Green Arrow co-creator Mort Weisinger.[56]

He began drawing

Marvel Comics in the Silver Age (1958–1970)

Several months later, after his split with DC, Kirby began freelancing regularly for Atlas despite harboring negative sentiments about Stan Lee (the cousin of Timely publisher Martin Goodman's wife), who Kirby had always found annoying on top of his aforementioned betrayal he suspected in the 1940s. Because of the poor page rates, Kirby would spend 12 to 14 hours daily at his drawing table at home, producing four to five pages of artwork a day.

It was at Marvel that Kirby hit his stride once again in superhero comics, beginning with

Jack was the single most influential figure in the turnaround in Marvel's fortunes from the time he rejoined the company ... It wasn't merely that Jack conceived most of the characters that are being done, but ... Jack's point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field ... [Marvel took] Jack and use[d] him as a primer. They would get artists ... and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby ... Jack was like the Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That's what was told to me ... It was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view.[69]

Highlights of Kirby's tenure also include the

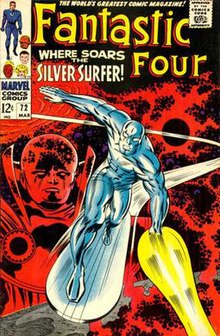

The story frequently cited as Lee and Kirby's finest achievement[82][83] is "The Galactus Trilogy" in Fantastic Four #48–50 (March–May 1966), chronicling the arrival of Galactus, a cosmic giant who wanted to devour the planet, and his herald, the Silver Surfer.[84][85] Fantastic Four #48 was chosen as #24 in the 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time poll of Marvel's readers in 2001. Editor Robert Greenberger wrote in his introduction to the story that "As the fourth year of the Fantastic Four came to a close, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby seemed to be only warming up. In retrospect, it was perhaps the most fertile period of any monthly title during the Marvel Age."[86] Comics historian Les Daniels noted that "[t]he mystical and metaphysical elements that took over the saga were perfectly suited to the tastes of young readers in the 1960s", and Lee soon discovered that the story was a favorite on college campuses.[87] Kirby continued to expand the medium's boundaries, devising photo-collage covers and interiors, developing new drawing techniques such as the method for depicting energy fields now known as "Kirby Krackle", and other experiments.[88]

In 1968 and 1969, Joe Simon was involved in litigation with Marvel Comics over the ownership of Captain America, initiated by Marvel after Simon registered the copyright renewal for Captain America in his own name. According to Simon, Kirby agreed to support the company in the litigation and, as part of a deal Kirby made with publisher Martin Goodman, signed over to Marvel any rights he might have had to the character.[89]

At this same time, Kirby grew increasingly dissatisfied with working at Marvel, for reasons Kirby biographer Mark Evanier has suggested include resentment over Lee's media prominence, a lack of full creative control, anger over breaches of perceived promises by publisher Martin Goodman, and frustration over Marvel's failure to credit him specifically for his story plotting and for his character creations and co-creations.[90] He began to both write and draw some secondary features for Marvel, such as "The Inhumans" in Amazing Adventures volume two,[91] as well as horror stories for the anthology title Chamber of Darkness, and received full credit for doing so; but in 1970, Kirby was presented with a contract that included unfavorable terms such as a prohibition against legal retaliation. When Kirby objected, the management refused to negotiate any contract changes, bluntly dismissing his contribution to Marvel's success since they considered Lee solely responsible.[92] Kirby, although he was earning $35,000 a year freelancing for the company[93] (adjusted for inflation, the equivalent of almost $234,000 in 2021),[94] subsequently left Marvel in 1970 for rival DC Comics, under editorial director Carmine Infantino.[95]

DC Comics and the Fourth World saga (1971–1975)

Kirby spent nearly two years negotiating a deal to move to DC Comics,

The three books Kirby originated dealt with aspects of mythology he had previously touched upon in Thor. The New Gods would establish this new mythos, while in The Forever People Kirby would attempt to mythologize the lives of the young people he observed around him. The third book, Mister Miracle was more of a personal myth. The title character was an escape artist, which Mark Evanier suggests Kirby channeled his feelings of constraint into. Mister Miracle's wife was based in character on Kirby's wife Roz, and he even caricatured Stan Lee within the pages of the book as Funky Flashman, a depiction Lee found hurtful while Kirby tried to downplay the insult when confronted about it by Lee's protege, Roy Thomas, who was similarly insulted with Flashman's sidekick, Houseroy.[101][102]

The central villain of the Fourth World series, Darkseid, and some of the Fourth World concepts, appeared in Jimmy Olsen before the launch of the other Fourth World books, giving the new titles greater exposure to potential buyers. The Superman figures and Jimmy Olsen faces drawn by Kirby were redrawn by Al Plastino, and later by Murphy Anderson.[103][104] Les Daniels observed in 1995 that "Kirby's mix of slang and myth, science fiction and the Bible, made for a heady brew, but the scope of his vision has endured."[105] In 2007, comics writer Grant Morrison commented that "Kirby's dramas were staged across Jungian vistas of raw symbol and storm ... The Fourth World saga crackles with the voltage of Jack Kirby's boundless imagination let loose onto paper."[106]

In addition to his artistic efforts, Kirby proposed a variety of new formats for comics such as planning to collect his published Fourth World stories into square-bound books, a format that would later be called the trade paperback, which would eventually become standard practice in the industry. However, Infantino and company were not receptive and Kirby's proposals only went as far as producing the one-shot black-and-white magazines Spirit World and In the Days of the Mob in 1971.[107]

Kirby later produced other DC series such as

Kirby's production assistant of the time, Mark Evanier, recounted that DC's policies of the era were not in sync with Kirby's creative impulses, and that he was often forced to work on characters and projects he did not like.[104] Meanwhile, some artists at DC did not want Kirby there, as he threatened their positions in the company; they also had bad blood from previous competition with Marvel and legal problems with him. Since he was working from California, they were able to undermine his work through redesigns in the New York office.[117]

Return to Marvel (1976–1978)

At the comic book convention Marvelcon '75, in 1975, Stan Lee used a Fantastic Four panel discussion to announce that Kirby was returning to Marvel after having left in 1970 to work for DC Comics. Lee wrote in his monthly column, "Stan Lee's Soapbox", "I mentioned that I had a special announcement to make. As I started telling about Jack's return, to a totally incredulous audience, everyone's head started to snap around as Kirby himself came waltzin' down the aisle to join us on the rostrum! You can imagine how it felt clownin' around with the co-creator of most of Marvel's greatest strips once more."[118]

Back at Marvel, Kirby both wrote and drew the monthly Captain America series[119] as well as the Captain America's Bicentennial Battles one-shot in the oversized treasury format.[120] He created the series The Eternals,[121] which featured a race of inscrutable alien giants, the Celestials, whose behind-the-scenes intervention in primordial humanity would eventually become a core element of Marvel Universe continuity. He produced an adaptation and expansion of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey,[122] as well as an abortive attempt to do the same for the classic television series The Prisoner.[123] He wrote and drew Black Panther and drew numerous covers across the line.[14]

Kirby's other Marvel creations in this period include Machine Man[124] and Devil Dinosaur.[125] Kirby's final comics collaboration with Stan Lee, The Silver Surfer: The Ultimate Cosmic Experience, was published in 1978 as part of the Marvel Fireside Books series and is considered Marvel's first graphic novel.[126]

Film and animation (1979–1980)

Still dissatisfied with Marvel's treatment of him,

In 1979, Kirby drew concept art for film producer Barry Geller's script treatment adapting

Final years (1981–1994)

In the early 1980s, Kirby and

In 1983 Richard Kyle commissioned Kirby to create a 10-page autobiographical strip, "

In the twilight of his life, Kirby spent a great deal of time sparring with Marvel executives over the ownership rights of his original page boards. At Marvel, many of these pages owned by the company (due to outdated and legally dubious copyright claims) were given away as promotional gifts to Marvel clients or simply stolen from company warehouses.[144] After the passage of the Copyright Act of 1976, which greatly expanded artist copyright capabilities, comics publishers began to return original art to creators, but in Marvel's case only if they signed a release reaffirming Marvel's ownership of the copyright. In 1985, Marvel issued a release that demanded Kirby affirm that his art was created for hire, allowing Marvel to retain copyright in perpetuity, in addition to demanding that Kirby forego all future royalties. Marvel offered him 88 pages of his art (less than 1% of his total output) if he signed the agreement, but reserved the right to reclaim the art if Kirby violated the deal.[145] After Kirby publicly slammed Marvel, calling the company thugs and claiming they were arbitrarily holding his creations, Marvel finally returned (after two years of deliberations) approximately 1,900[146] or 2,100 pages of the estimated 10,000 to 13,000 Kirby drew for the company.[147][148]

For the producer

For

Personal life and death

In the early 1940s, Kirby and his family moved to Brooklyn. There, Kirby met Rosalind "Roz" Goldstein, who lived in the same apartment building. The pair began dating soon afterward.[156] Kirby proposed to Goldstein on her 18th birthday, and the two became engaged.[157] They married on May 23, 1942.[158] The couple had four children together: Susan (b. December 6, 1945),[159] Neal (b. May 1948),[40] Barbara (b. November 1952),[160] and Lisa (b. September 1960).[159][161]

After being

In 1949, Kirby bought a house for his family in Mineola, New York, on Long Island.[40] This would be the family's home for the next 20 years, with Kirby working out of a basement studio just 10 feet (3.0 m) wide, which the family referred to jocularly as "The Dungeon".[168] He moved the family to Southern California in early 1969, both to live in a drier climate for the sake of daughter Lisa's health, and to be closer to the Hollywood studios Kirby believed might provide work.[169]

In an interview, Kirby's granddaughter Jillian Kirby said Kirby was a "liberal Democrat".[170] Kirby held anti-communist views, once saying that "I was against the reds. I became a witch hunter. My enemies were the commies — I called them commies. In fact, Granny Goodness was a commie, Doubleheader was a commie."[171]

On February 6, 1994, aged 76, Kirby died of heart failure in his Thousand Oaks, California home.[172] He was buried at Valley Oaks Memorial Park in Westlake Village, California.

Artistic style and achievements

Brent Staples wrote in the New York Times:

He created a new grammar of storytelling and a cinematic style of motion. Once-wooden characters cascaded from one frame to another—or even from page to page—threatening to fall right out of the book into the reader's lap. The force of punches thrown was visibly and explosively evident. Even at rest, a Kirby character pulsed with tension and energy in a way that makes movie versions of the same characters seem static by comparison.[173]

Jack Kirby has been referred to as the "superhero of style", his artwork described by John Carlin in Masters of American Comics as "deliberately primitive and bombastic",[174] and elsewhere has been compared to Cubist,[175] Futurist, Primitivist and outsider art.[176] His contributions to the comic book form, including the many characters he created or co-created and the many genres he worked on have led to him being referred to as the definitive comic book artist.[177] Given the number of places Kirby's artwork can now be found, the toys based on his designs, and the success of the movies based upon his work, Charles Hatfield and Ben Saunders declare him "one of the chief architects of the American imagination."[178] He was regarded as a hard working artist, and it has been calculated that he drew at least 20,318 pages of published art and a further 1,385 covers in his career. He published 1,158 pages in 1962 alone.[179] Kirby defined comics in two periods. His work in the early 1940s with Joe Simon on the Captain America strip, and then his superhero comics of the 1960s with Stan Lee at Marvel Comics and on his own at DC Comics.[180] Kirby also created stories in almost every genre of comics, from the autobiographical Street Code to the apocalyptic science fiction fantasy of Kamandi.[181]

Narrative approach to comics

Like many of his contemporaries, Kirby was hugely indebted to Milton Caniff, Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, who codified many of the tropes of narrative art in adventure comic strips. It has also been suggested that Kirby drew from Burne Hogarth, whose dynamic figure work may have informed the way Kirby drew figures; "his ferocious bounding, and grotesquely articulated figures seem directly descended from Hogarth's dynamically contorted forms."[182] His style drew on these influences, all major artists at the time Kirby was learning his craft, with Caniff, Foster and Raymond between them imparting to the sequential adventure comic strip a highly illustrative approach based on realizing the setting to a very high degree. Where Kirby diverged from these influences, and where his style impacted on the formation of comic book art, was in his move away from an illustrated approach to one that was more dynamic. Kirby's artistic style was one that captured energy and motion within the image, synergizing with the text and helping to serve the narrative. In contrast, successors to the illustrative approach, such as Gil Kane, found their work eventually reach an impasse. The art would illustrate, but in lacking movement caused the reader to contemplate the art as much as the written word. Later artists such as Bryan Hitch and Alex Ross combined the Kirby and Kane approaches, using highly realistic backgrounds contrasted with dynamic characters to create what became known as a widescreen approach to comics.[183]

Kirby's dynamism and energy served to push the reader through the story where an illustrative, detailed approach would cause the eye to linger.[184] His reduction of the presentation of a given scene down to one that represents the semblance of movement has led Kirby to be described as cinematic in his style.[185] Having worked at Fleischer Studios before coming to comics, Kirby had a grounding in animation techniques for producing motion. He also realized that comic books were not subject to the same constraints as the newspaper strip. While other comic book artists recreated the layouts that format used, Kirby swiftly utilized the space a whole comic book page created.[180] As Ron Goulart describes, "(h)e broke up the pages in new ways and introduced splash panels that stretched across two pages."[186] Kirby himself described the creation of his dynamic style as a reaction both to the cinema and to the urge to create and compete: "I found myself competing with the movie camera. I had to compete with the camera. I felt like John Henry ... I tore my characters out of the panels. I made them jump all over the page. I tried to make that cohesive so that it would be easier to read ... I had to get my characters in extreme positions, and in doing so I created an extreme style which was recognizable by everybody."[187]

Style

In the early 1940s Kirby would at times disregard panel borders. A character would be drawn in one panel, but their shoulder and arm would extend outside the border, into the gutter and sometimes on top of a nearby panel. A character may be punched out of one panel, feet being in the original panel and body in the next. Panels themselves would overlap, and Kirby would find new ways to arrange panels on a comic book page. His figures were depicted as lithe and graceful, although Kirby would place them thrusting from the page towards the reader.[188][176][189] The late 1940s and 1950s saw Kirby move away from superhero comics and, working with Joe Simon, try his hand at a number of genres. Kirby and Simon created the romance comics genre, and working in this as well as the war, Western and crime genres saw Kirby's style change. He left behind the diverse panel framing and layouts. The nature of these genres enabled him to channel the energy into the posing and blocking of characters, forcing the drama into the constraints of the panel.[176]

When Kirby and

Kirby's style in the late 1960s was regarded so highly by Stan Lee that he instituted it as Marvel's house style. Lee would instruct other artists to draw more like Jack, and would also assign them books to work on using Kirby's breakdowns of the story so that they could more closely hew to Kirby's style.[196] Over time, Kirby's style has become so well known that imitations, homages and pastiche are referred to as Kirbyesque.[197][198][199][200]

Working method

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Kirby did not use preliminary sketches, rough work or layouts. He would instead start with the blank board and draw the story onto the page from top to bottom, start to finish. Many artists, including Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane and Jim Steranko have remarked on the unusual nature of his method. Kirby would rarely erase while working; the art, and therefore the story, would flow from him almost fully formed.[209] Kirby's pencils had a reputation for being detailed, to the point that they were difficult to ink.[210][211] Will Eisner remembers even in the early years that Kirby's pencils were "tight".[212] Working for Eisner, Kirby initially inked with a pen, not confident enough in his ability to use the Japanese brushes Lou Fine and Eisner preferred.[213] By the time Kirby worked with Joe Simon, Kirby had taught himself to use a brush, and would on occasion ink over inked work where he felt it was needed.[214]

Due to the amount of work Kirby produced, it was rare for him to ink his own work. Instead the pencilled pages were sent on to an inker; different inkers left their own stylistic stamp on the published version. As Kirby noted, individual inkers were suited to different genres.[215] Harry Mendryk has suggested that for a period in the 1950s, Kirby inked himself due to other work drying up.[216] By the late 1960s, Kirby preferred to pencil, feeling that "inking in itself is a separate kind of art."[215] Stan Lee recalls Kirby not really being too interested in who inked him: "I cared much more about who inked Kirby than Kirby did ... Kirby never seemed to care who inked him ... I think Kirby felt his style was so strong that it just didn't matter who inked him".[217] Chic Stone, an inker of Kirby's during the 1960s at Marvel, recalled "(T)he two best [inkers] for Jack were Mike Royer and Steve Rude. Both truly maintained the integrity of Jack's pencils."[218]

The size of the art board made a difference to Kirby's style. During the late 1960s the industry shrunk the size of the art board artists used. Prior to 1967, art boards were around 14 x 21 inches, being reproduced at 7 x 10 inches. After 1967 the size of the board shrunk to 10 x 15.[219] This affected the way Kirby drew. Gil Kane noted that "the amount of space around the figures became less and less ... The figures became bigger and bigger, and they couldn't be contained by a single panel or even a single page".[220] Professor Craig Fischer asserts Kirby at first "hated" the new size.[221] Fischer argues that it took Kirby around 18 months to negotiate a way of working at the smaller size. Initially he retreated to a less detailed, close up style, as seen in Fantastic Four #68. In adjusting to the new size, Kirby began utilizing depth to bring the pages to life, increasing his use of foreshortening.[221] By the time Kirby had moved to DC, he started to incorporate the use of two-page spreads into his art more. These spreads helped define the mood of the story, and came to define Kirby's late era work.[222]

Exhibitions and original art

Kirby's art has been exhibited as part of the Masters of American Comics joint exhibition by

Kirby's original art regularly sells at auction, with Heritage Auctions listing the cover of Tales of Suspense #84, inked by Frank Giacoia as realizing a price of $167,300 in a February 2014 auction.[228] A large portion of Kirby's art remains unaccounted for. Work created around World War II would have been reused or pulped due to paper shortages. DC Comics had a policy of destroying original art in the 1950s. Marvel Comics would also destroy art, up until 1960, when it stored artwork prior to a policy which saw art returned to the artist. In Kirby's case, it's reported he was returned roughly 2,100 pieces of the estimated 10,000 pages drawn. The whereabouts of these missing pages are unknown, although some do turn up for sale, provenance unknown.[229][230]

Kirby's estate

Subsequent releases

Lisa Kirby announced in early 2006 that she and co-writer Steve Robertson, with artist Mike Thibodeaux, planned to publish via the Marvel Comics Icon imprint a six-issue limited series, Jack Kirby's Galactic Bounty Hunters, featuring characters and concepts created by her father for Captain Victory.[161] The series, scripted by Lisa Kirby, Robertson, Thibodeaux, and Richard French, with pencil art by Jack Kirby and Thibodeaux, and inking by Scott Hanna and Karl Kesel primarily, ran an initial five issues (Sept. 2006–Jan. 2007) and then a later final issue (Sept. 2007).[231]

Marvel posthumously published a "lost" Kirby/Lee Fantastic Four story, Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure (April 2008), with unused pages Kirby had originally drawn for a story that was partially published in Fantastic Four #108 (March 1971).[232][233]

In 2011, Dynamite Entertainment published Kirby: Genesis, an eight-issue miniseries by writer Kurt Busiek and artists Jack Herbert and Alex Ross, featuring Kirby-owned characters previously published by Pacific Comics and Topps Comics.[234][235]

Copyright dispute

On September 16, 2009,

Legacy

- Glen David Gold wrote in Masters of American Comics that, "Kirby elevates all of us into a realm where we fly among the beating wings of the immortal and the omnipotent, the gods and the monsters, so that we, dreamers all, can play host to the demons of creation, can become our own myths.[248]

- Michael Chabon, in his afterword to his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, a fictional account of two early comics pioneers, wrote, "I want to acknowledge the deep debt I owe in this and everything else I've ever written to the work of the late Jack Kirby, the King of Comics."[249]

- Director James Cameron said Kirby inspired the look of his film Aliens, calling it "not intentional in the sense I sat down and looked at all my favorite comics and studied them for this film, but, yeah, Kirby's work was definitely in my subconscious programming. The guy was a visionary. Absolutely. And he could draw machines like nobody's business. He was sort of like A. E. van Vogt and some of these other science-fiction writers who are able to create worlds that — even though we live in a science-fictionary world today — are still so far beyond what we're experiencing."[250]

- Several Kirby images are among those on the "Marvel Super Heroes" set of commemorative stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service on July 27, 2007.[251] Ten of the stamps are portraits of individual Marvel characters and the other 10 stamps depict individual Marvel comic book covers. According to the credits printed on the back of the pane, Kirby's artwork is featured on: Captain America, The Thing, Silver Surfer, The Amazing Spider-Man #1, The Incredible Hulk #1, Captain America #100, The X-Men #1, and The Fantastic Four #3.[173][251]

- In the 1990s Superman: The Animated Series television show, police detective Dan Turpin was modeled on Kirby.[252]

- In the 1998 episode "The Demon Within" of The New Batman Adventures, Klarion has Etrigan break into the Kirby Cake Company. Both characters were created by Kirby.

- In 2002, jazz percussionist Zenn-La".[253]

- The Cartoon Network/Adult Swim series Minoriteam uses artwork as a homage to Jack Kirby (credited under Jack "The King" Kirby, who is credited under special thanks in the show's end credits).

- Various comic-book and cartoon creators have done homages to Kirby. Examples include the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Mirage Comics series ("Kirby and the Warp Crystal" in Donatello #1, and its animated counterpart, "The King", from the 2003 cartoon series). The episode of Superman: The Animated Series entitled "Apokolips ... Now!, Part 2" was dedicated to his memory.[254][255]

- As of June 2018, Hollywood films based on characters Kirby co-created have collectively earned nearly US$7.4 billion.[256] Kirby himself is a character portrayed by Luis Yagüe in the 2009 Spanish short film The King & the Worst, which is inspired by Kirby's service in World War II.[257] He is portrayed by Michael Parks in a brief appearance in the fact-based drama Argo (2012), about the Canadian Caper.[258]

- A play based on Kirby's life, King Kirby, by Crystal Skillman and New York Times bestselling comics writer Fred Van Lente, was staged at Brooklyn's Brick Theater as part of its annual Comic Book Theater Festival. The play was a New York Times Critics' Pick selection and was funded by a widely publicized Kickstarter campaign.[259][260]

- The 2016 novel I Hate the Internet frequently mentions Kirby as a "central personage" of the novel.[261]

- To mark Jack Kirby's 100th birthday in 2017, DC Comics announced a series of one-shots involving characters that Kirby had created, including The Newsboy Legion and the Boy Commandos, Manhunter, Sandman, the New Gods, Darkseid, and ending with The Black Racer and Shilo Norman.[262]

- In May 2004, in Fantastic Four issue #511 (written by Mark Waid and penciled by Mike Weiringo), Reed, Sue, and Johnny travel to Heaven to recover the soul of the deceased Ben Grimm. After passing a trial, they are allowed to meet God himself, who is depicted as Jack Kirby. God explains that he is seen by them as what he is to them, and that he considers the fact that they see him as Kirby to be an honor.

- Supreme series, Supreme #62 (The Return #6) "New Jack City" (March 2000), illustrated by Rob Liefeld and, for the Kirbyesque part, Rick Veitch. In this story Supreme enters a realm of pure ideas where he meets a gigantic floating Jack Kirby head, smoking a cigar. "This gigantic entity explains to him that he used to be a flesh and blood artist but now he is entirely in the realm of ideas, which is much better because flesh and blood has its limitations because he can only do four or five pages a day tops, where now he exists purely in the world of ideas".[263]

- The Disney California Adventure attraction Guardians of the Galaxy – Mission: Breakout! is surrounded by markings on the ground that serve as a tribute to the Kirby Krackle.[264]

- The 1995 video game Marvel Super Heroes was dedicated to Kirby.

Filmography

- Kirby guest starred in the episode "Bounty Hunter" of Starsky & Hutch as an Officer.

- Kirby made an un-credited cameo appearance in the episode "No Escape" of The Incredible Hulk. He can be spotted in the hospital scene as a police sketch artist who is recreating, from the witness's description, a picture of the man he claimed to have saved his life. Instead of resembling the live-action Hulk, this illustration is instantly recognizable as the Hulk as he appeared in the original comics.

- Kirby appeared as himself in the episode "You Can't Win" of Bob.

Awards and honors

Jack Kirby received a great deal of recognition over the course of his career, including the 1967 Alley Award for Best Pencil Artist.[265] The following year he was runner-up behind Jim Steranko. His other Alley Awards were:

- 1963: Favorite Short Story – "The Human Torch Meets Captain America", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Strange Tales #114[266]

- 1964:[267]

- Best Novel – "Captain America Joins the Avengers", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, from The Avengers #4

- Best New Strip or Book – "Captain America", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Tales of Suspense

- 1965: Best Short Story – "The Origin of the Red Skull", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Tales of Suspense #66[268]

- 1966: Best Professional Work, Regular Short Feature – "Tales of Asgard" by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Thor[269]

- 1967: Best Professional Work, Regular Short Feature – (tie) "Tales of Asgard" and "Tales of the Inhumans", both by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Thor[265]

- 1968:[270]

- Best Professional Work, Best Regular Short Feature – "Tales of the Inhumans", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Thor

- Best Professional Work, Hall of Fame – Fantastic Four, by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., by Jim Steranko[270]

Kirby won a

His work was honored posthumously in 1998: The collection of his New Gods material, Jack Kirby's New Gods, edited by Bob Kahan, won both the

The

With

Asteroid

Bibliography

This is an abridged listing of Kirby's comics work (interior pencil art) for the two main comics publishers, DC Comics and Marvel Comics. For his work at DC it lists any title Kirby worked on for eight or more issues between 1970 and 1976. Of his Marvel Comics work, it lists any title Kirby worked on for eight or more issues between 1959 and 1978.

DC Comics

- Demon #1–16 (1972–1974)

- Forever People #1–11 (1971–1972)

- Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth #1–40 (1972–1976)

- Mister Miracle #1–18 (1971–1974)

- New Gods #1–11 (1971–1972)

- O.M.A.C. #1–8 (1974–1975)

- Our Fighting Forces (The Losers) #151–162 (1974–1975)

- Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133–139, 141–148 (1970–1972)

Marvel Comics

- Amazing Adventures #1–4 (Inhumans) (1970)

- Avengers #1–8 (full pencils), #14–17 (layouts only, pencils by Don Heck) (1963–1965)

- Black Panther#1–12 (1977–1978)

- Captain America #100–109, 112 (1968–1969); #193–214, Annual #3–4 (1976–1977)

- Devil Dinosaur #1–9 (1978)

- Eternals #1–19, Annual #1 (1976–1978)

- Fantastic Four #1–102, 108, Annual #1–6 (1961–1971)

- Incredible Hulk #1–5 (1962–1963)

- Journey into Mystery #51–52, 54–82 (1959–1962); (Thor): #83–89, 93, 97–125, Annual #1 (1962–1966)

- Machine Man #1–9 (1978)

- Silver Surfer #18 (1970)

- Strange Tales #67–70, 72–100 (1959–1962); (Human Torch): #101–105, 108–109, 114, 120, Annual #2 (1962–1964); (Nick Fury): #135, 141–142 (full pencils), 136–140, 143–153 (layouts only, pencils by John Severin, Jim Steranko and others) (1965–1967)

- Tales of Suspense #2–4, 7–35 (1959–1962); (Iron Man): #41, 43 (1963); (Captain America): #59–68, 78–86, 92–99 (full pencils), #69–75, 77 (layouts only) (1964–1968)

- Sub-Mariner): #82 (1966)

- Thor #126–177, 179, Annual #2 (1966–1970)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey #1–10 (1976–1977)

- X-Men #1–11 (full pencils) (1963–1965), #12–17 (layouts only, pencils by Alex Toth and Werner Roth) (1965–1966)

References

Citations

- YouTube

- ^ Morrison, Grant (July 23, 2011). "My Supergods from the Age of the Superhero". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Evanier, Mark; Sherman, Steve; et al. (March 20, 2008). "Jack Kirby Biography". Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center. Archived from the original on September 17, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-59928-298-5, p. 4

- ^ Rob Stiebel. "Jack Kirby Interview – Part III". Jack Kirby Museum.

- YouTube

- ^ Jones 2004, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Evanier 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 196.

- Fantagraphics Books. February 1990. Reprinted in George 2002, p. 22

- ^ [1] Archived September 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine at Cartoon Research.com.

- ^ Interview, The Comics Journal #134, reprinted in George 2002, p. 24

- ^ Interview, The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, reprinted in George 2002, p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jack Kirby Archived April 13, 2019, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 197.

- ^ "More Than Your Average Joe – Excerpts from Joe Simon's panels at the 1998 San Diego Comic-Con International". The Jack Kirby Collector (25). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. August 1999. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010.

- comics.org. Archivedfrom the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Mendryk, Harry (November 19, 2011). "In the Beginning, Chapter 10, Captain Marvel and Others". Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0756641238.

Simon and Kirby decided to create another hero who was their response to totalitarian tyranny abroad.

- ^ a b Ro 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Markstein, Don (2010). "Captain America". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

Captain America was the first successful character published by the company that would become Marvel Comics to debut in his own comic. Captain America Comics #1 was dated March, 1941.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 200.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 25-26.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Van Lente & Dunlavey 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 30.

- ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

Hot properties Joe Simon and Jack Kirby joined DC ... [and] after taking over the Sandman and Sandy, the Golden Boy feature in Adventure Comics #72, the writer and artist team turned their attentions to Manhunter with issue #73.

- ^ Wallace "1940s" in Dolan, p. 41 "The inaugural issue of Boy Commandos represented Joe Simon and Jack Kirby's first original title since they started at DC (though the characters had debuted earlier that year in Detective Comics #64.)"

- ^ a b Ro 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Wallace "1940s" in Dolan, p. 41 "Joe Simon and Jack Kirby took their talents to a second title with Star-Spangled Comics, tackling both the Guardian and the Newsboy Legion in issue #7."

- ISBN 978-3-83651-981-6.

- ^ a b Ro 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Ro 2004, pp. 35.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 45.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-887591-35-5, pp. 123–125

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Ro 2004, p. 46.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-91303-563-4.

- ^ Simon, p. 125

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 52.

- ^ a b Ro 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Beerbohm, Robert Lee (August 1999). "The Mainline Story". The Jack Kirby Collector (25). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ISBN 1-56685-006-1.

- ISBN 978-1-887591-35-5. Page numbers refer to 1990 edition.

- ^ Mainline Archived November 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 56.

- WNUR-FM, Northwestern University. May 14, 1971. Transcribed in The Nostalgia Journal(27) August 1976. Reprinted in George 2002, p. 16

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 60.

- Kid Colt Outlaw#86 (Sept. 1959; 5 pp.)

- Irvine, Alex"1950s" in Dolan, p. 84: "Kirby's first solo project was a test run of a non-super hero adventure team called Challengers of the Unknown. Appearing for the first time in Showcase #6, the team would make a few more Showcase appearances before springing into their own title in May 1958."

- ^ Evanier, Mark (2001). "Introduction". The Green Arrow. New York, New York: DC Comics.

All were inked by Jack with the aid of his dear spouse, Rosalind. She would trace his pencil work with a static pen line; he would then take a brush, put in all the shadows and bold areas and, where necessary, heavy-up the lines she'd laid down. (Jack hated inking and only did it because he needed the money. After departing DC this time, he almost never inked his own work again.)

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Evanier 2008, pp. 103–106 "The artwork was exquisite, in no small part because Dave Wood had the idea to hire Wally Wood (no relation) to handle the inking."

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 282.

- ^ Christiansen, Jeff (March 10, 2011). "Groot". Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013.

- ^ Christiansen, Jeff (January 17, 2007). "Grottu". Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013.

- ^ Markstein, Don (2009). "The Fly". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014.

- ^ Markstein, Don (2007). "The Shield". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013.

- ^ DeFalco, Tom "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 84: "It did not take long for editor Stan Lee to realize that The Fantastic Four was a hit ... the flurry of fan letters all pointed to the FF's explosive popularity."

- ^ "Challengers of the Unknown = Fantastic Four". The Great American Novel. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8225-6654-0. Archivedfrom the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

Readers ... liked seeing Reed and Sue bicker, Johnny annoying everyone, and Ben being grumpy. ... Kirby's vivid illustrations created a whole new style for Marvel, where the imaginative art matched the colorful, loose style of the time.

- .

The liberalization of American culture allowed superhero comic books to challenge the assumptions behind 1950s censorship. ... Marvel was able to position themselves as a publishing maverick. Several of their new superheroes, including the Fantastic Four and the Amazing Spider-Man were able to reflect real-world sensibilities and problems. Other heroes such as the Invincible Iron Man and the Silver Surfer examined the political landscape of the 1960s. The close bonds shared with youth culture meant that superheroes had reasserted themselves into the American national consciousness.

- ^ Gil Kane, speaking at a forum on July 6, 1985, at the Dallas Fantasy Fair. As quoted in George 2002, p. 109

- ^ Cronin, Brian (September 18, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 261". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 111: "The Inhumans, a lost race that diverged from humankind 25,000 years ago and became genetically enhanced."

- ^ Cronin, Brian (September 19, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 262". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Parker, Ryan (February 15, 2018). "'Black Panther' Co-Creator Jack Kirby Would've Adored Film Phenomenon, Family Says". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 117: Stan Lee wanted to do his part by creating the first black super hero. Lee discussed his ideas with Jack Kirby and the result was seen in Fantastic Four #52.

- ISBN 1-56685-011-8.

- ISBN 978-0756692360.)

Kirby had the honor of being the first ever penciler to take a swing at drawing Spider-Man. Though his illustrations for the pages of Amazing Fantasy #15 were eventually redrawn by Steve Ditko after Stan Lee decided that Kirby's Spidey wasn't quite youthful enough, the King nevertheless contributed the issue's historic cover.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 94: "Filled with some wonderful visual action, The Avengers #1 has a very simple story: the Norse god Loki tricked the Hulk into going on a rampage ... The heroes eventually learned about Loki's involvement and united with the Hulk to form the Avengers."

- ^ Virtue, Graeme (August 28, 2017). "Captain America, X-Men, Iron Man, the Avengers ... Jack Kirby, king of comics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 86: "Stan Lee and Jack Kirby reintroduced one of Marvel's most popular Golden Age heroes – Namor, the Sub-Mariner."

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 99: "'Captain America lives again!' announced the cover of The Avengers #4 ... Cap was back."

- ISBN 978-1-4422-7781-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-1893905009.

- ISBN 978-0762428441.

Then came the issues of all issues, the instant legend, the trilogy of Fantastic Four (#48-50) that excited readers immediately christened 'the Galactus Trilogy', a designation still widely recognized four decades later.

- ^ Cronin, Brian (February 19, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 50". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 115: "Stan Lee may have started the creative discussion that culminated in Galactus, but the inclusion of the Silver Surfer in Fantastic Four #48 was pure Jack Kirby. Kirby realized that a being like Galactus required an equally impressive herald."

- ^ Greenberger, Robert, ed. (December 2001). 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time. Marvel Comics. p. 26.

- ISBN 978-0-81093-821-2.

- ^ Foley, Shane (November 2001). "Kracklin' Kirby: Tracing the advent of Kirby Krackle". The Jack Kirby Collector (33). Archived from the original on November 30, 2010.

- ^ Simon, p. 205

- ^ Evanier 2008, pp. 126–163.

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 146: "As Marvel was expanding its line of comics, the company decided to introduce two new 'split' books ... Amazing Adventures and Astonishing Tales. Amazing Adventures contained a series about the genetically enhanced Inhumans and a series about intelligence agent the Black Widow."

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Braun, Saul (May 2, 1971). "Shazam! Here Comes Captain Relevant". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2012.

- ^ "Inflation Calculator Determines Change in Dollar and Rates over Time". Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Van Lente & Dunlavey 2012, p. 115.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 139.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 143.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael "1970s" in Dolan, p. 145 "As the writer, artist, and editor of the Fourth World family of interlocking titles, each of which possessed its own distinct tone and theme, Jack Kirby cemented his legacy as a pioneer of grand-scale storytelling."

- ^ Evanier, Mark. "Afterword." Jack Kirby's Fourth World Omnibus; Volume 1, New York: DC Comics, 2007.

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 141 "Since no ongoing creative team had been slated to Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen, "King of Comics" Jack Kirby made the title his DC launch point, and the writer/artist's indelible energy and ideas permeated every panel and word balloon of the comic."

- ISBN 978-1-61374-292-1.

- ^ Evanier 2008, pp. 172–177.

- ^ Evanier, Mark (August 22, 2003). "Jack Kirby's Superman". POV Online. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

Plastino drew new Superman figures and Olsen heads in roughly the same poses and positions, and these were pasted into the artwork.

- ^ Fictioneer Books. pp. 23–34.

- ISBN 0821220764.

- ISBN 978-1401213442.

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 147: "Believing that new formats were necessary for the comics medium to continue evolving, Kirby oversaw the production of what was labeled his 'Speak-Out Series' of magazines: Spirit World and In the Days of the Mob ... Sadly, these unique magazines never found their desired audience."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 161 "In OMAC's first issue, editor/writer/artist Jack Kirby warned readers of "The World That's Coming!", a future world containing wild concepts that are almost frighteningly real today."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 153 "Kirby had already introduced a similar concept and characters in Alarming Tales #1 (1957) ... Coupling the premise with his unpublished "Kamandi of the Caves" newspaper strip, Kirby's Last Boy on Earth roamed a world that had been ravaged by the "Great Disaster" and taken over by talking animals."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 152 "While his "Fourth World" opus was winding down, Jack Kirby was busy conjuring his next creation, which emerged not from the furthest reaches of the galaxy but from the deepest pits of Hell. Etrigan was hardly the usual Kirby protagonist."

- ^ Kelly, Rob (August 2009). "Kobra". Back Issue! (35). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 63.

Maybe that's because Kobra was the creation of the legendary Jack 'King' Kirby, who wrote and penciled the first issue's story, 'Fangs of the Kobra!'

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 161 "Jack Kirby also took on a group of established DC characters that had nothing to lose. The result was a year-long run of Our Fighting Forces tales that were action-packed, personal, and among the most beloved of World War II comics ever produced."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 158 "The legendary tandem of writer Joe Simon and artist/editor Jack Kirby reunited for a one-shot starring the Sandman ... Despite the issue's popularity, it would be Simon and Kirby's last collaboration."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 162: "Debuting with Atlas the Great, writer and artist Jack Kirby didn't shrug at the chance to put his spin on the well-known hero."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 164: "Though 1st Issue Special was primarily DC's forum to introduce new characters and storylines, editor Jack Kirby used the series as an opportunity to revamp the Manhunter, whom he and writer Joe Simon had made famous in the 1940s."

- ^ Abramowitz, Jack (April 2014). "1st Issue Special It Was No Showcase (But It Was Never Meant To Be)". Back Issue! (71). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 40–47.

- ^ Ro 2004, chapters 12–13

- ^ Bullpen Bulletins: "The King is Back! 'Nuff Said!", in Marvel Comics cover-dated October 1975, including Fantastic Four #163

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 175: "After an absence of half a decade, Jack Kirby returned to Marvel Comics as writer, penciller, and editor of the series he and Joe Simon created back in 1941."

- ^ Powers, Tom (December 2012). "Kirby Celebrating America's 200th Birthday: Captain America's Bicentennial Battles". Back Issue! (61). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 46–49.

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 175: "Jack Kirby's most important creation for Marvel during his return in the 1970s was his epic series The Eternals"

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 180: "Marvel published its adaptation of director Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke's classic science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey as an oversize Marvel Treasury Special."

- ^ Hatfield, Charles (July 1996). "Once Upon A Time: Kirby's Prisoner". The Jack Kirby Collector (11). Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 185: "In [2001: A Space Odyssey] issue #8, cover dated July 1977, [Jack] Kirby introduced a robot whom he originally dubbed 'Mister Machine.' Marvel's 2001 series eventually came to an end but Kirby's robot protagonist went on to star in his own comic book series as Machine Man."

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 185: "Jack Kirby's final major creation for Marvel Comics was perhaps his most unusual hero: an intelligent dinosaur resembling a Tyrannosaurus rex."

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 187: "[In 1978], Simon & Schuster's Fireside Books published a paperback book titled The Silver Surfer by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby ... This book was later recognized as Marvel's first true graphic novel."

- ^ "Ploog & Kirby Quit Marvel over Contract Dispute", The Comics Journal #44, January 1979, p. 11.

- ^ Evanier, King of Comics, p. 189: "In 1978, an idea found him. It was an offer from the Hanna-Barbera cartoon studio in Hollywood."

- ^ Evanier. Kirby. pp. 189–191.

- ^ Fischer, Stuart (August 2014). "The Fantastic Four and Other Things: A Television History". Back Issue! (74). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 30.

Stan Lee was a consultant to this series, and Jack Kirby played a very important part in this show as an animator and helped design the show.

- ^ "Jack Kirby". Lambiek Comiclopedia. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014.

- ^ Bearman, Joshuah (April 24, 2007). "How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran". Wired. 15 (5). Archived from the original on August 23, 2010.

- ^ Catron, Michael (July 1981). "Kirby's Newest: Captain Victory". Amazing Heroes (2). Fantagraphics Books: 14.

- ISBN 978-1893905009. Archivedfrom the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Larsen, Erik (February 18, 2007). "One Fan's Opinion: Issue #73". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010.

- ^ Kean, Benjamin Ong Pang (July 29, 2007). "SDCC '07: Erik Larsen, Eric Stephenson on Image's Kirby Plans". Newsarama. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009.

- ^ Kean, Benjamin Ong Pang (May 2, 2007). "The Current Image: Erik Larsen on Jack Kirby's Silver Star". Newsarama. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009.

- ^ Markstein, Don (2006). "Destroyer Duck". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012.

[T]he centerpiece of the issue was Gerber's own Destroyer Duck ... himself. The artist who worked with Gerber was the legendary Jack Kirby, who, as co-creator of The Fantastic Four, The Avengers, X-Men and many other cornerstones of Marvel's success, had issues of his own with the company.

- ^ George 2002, p. 73

- ISBN 1893905004.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. "1980s" in Dolan, p. 208: "In association with the toy company Kenner, DC released a line of toys called Super Powers ... DC soon debuted a five-issue Super Powers miniseries plotted by comic book legend Jack 'King' Kirby, scripted by Joey Cavalieri, and with pencils by Adrian Gonzales."

- ^ Cronin, Brian (January 17, 2014). "Comic Book Legends Revealed #454". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014.

- Syfy Wire. December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Van Lente & Dunlavey 2012, p. 157.

- ^ Van Lente & Dunlavey 2012, pp. 157–160.

- ^ Dean, Michael (December 29, 2002). "Kirby and Goliath: The Fight for Jack Kirby's Marvel Artwork". The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Gold, Glen (April 1998). "The Stolen Art". The Jack Kirby Collector (19). Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ "Marvel Returns Art to Kirby, Adams". The Comics Journal (116). Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books: 15. July 1987.

- ^ Collected Jack Kirby Collector, p. 113, at Google Books

- ^ Pauls, J. B. "The Rewind: Doctor Mordrid". Living Myth Magazine. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-78648-505-5. Archivedfrom the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 207.

- ISBN 978-1-893905-57-3.

- ISBN 978-1-89390-502-3. Archivedfrom the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1605490052.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 57.

- ^ a b Morrow, John (April 1996). "Roz Kirby Interview Excerpts". The Jack Kirby Collector (10). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-56060-134-0.

- ^ a b Brady, Matt (April 20, 2006). "Lisa Kirby, Mike Thibodeaux, & Tom Brevoort on Galactic Bounty Hunters". Newsarama. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009.

- ^ Ro 2004, chapter 3

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 40.

- ^ World War II V-mail letter from Kirby to Rosalind, in George 2002, p. 117

- ^ Ro 2004, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Ro 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Kirby, Neal (April 9, 2012). "Growing Up Kirby: The Marvel memories of Jack Kirby's son". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ^ Evanier, 2008, pp. 157, 160 (unnumbered): "... drove Jack to distraction, and from there to Southern California. In early 1969, the Kirbys moved west. The main reason was daughter Lisa's asthma and her need to live in a drier climate [than in New York State]. But Jack had another reason. ... Kirby had hopes that being close to Hollywood might bring hm entry to the movie business. ... Film seemed like the next logical outlet for his creativity. ...

- ^ Beard, Jim (August 25, 2015). "Jack Kirby Week: Kirby4Heroes". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Groth, Gary (February 1990). "Jack Kirby Interview". The Comics Journal.

- ^ "Jack Kirby, 76; Created Comic-Book Superheroes". The New York Times. February 8, 1994. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Staples, Brent (August 26, 2007). "Jack Kirby, a Comic Book Genius, Is Finally Remembered". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014.

- ^ Carlin 2005, p. 101.

- ^ Hatfield & Saunders 2015, pp. 119–123.

- ^ a b c Hatfield & Saunders 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Carlin 2005, p. 261.

- ^ Hatfield & Saunders 2015, p. 9.

- ^ "1993: Jack Kirby: The Hardest Working Man in Comics by Steve Pastis". The Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center. April 28, 2018. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ ISSN 0194-7869. Reprinted in George 2002, p. 61-73

- ^ Hatfield 2012, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, p. 61.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, pp. 65–67.

- ISBN 1578067197.

- ISBN 0312345577.

- ^ Eisner 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, pp. 24–25, 69–73.

- ^ ISBN 0878057587.

- ^ a b Hatfield (2005), pp. 54–55

- ^ Fischer, Craig (November 21, 2011). "Kirby: Attention Paid". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Press. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-56097-501-4.

Muscles stretched magically, foreshortened shockingly.

- ISBN 1893905020

- ^ Evanier 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Hatfield & Saunders 2015, pp. 89–99.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, p. 9.

- ISSN 0194-7869.

- ISBN 978-0-71483-993-6.

- ISBN 978-1893905757.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "The Rick Veitch Interview". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Press. May 24, 2013. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2018. Originally published in The Comics Journal #175 (March 1995)

- ^ Crowder, Craig (2010). "Kirby, Jack". In Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 353.

- ^ Foley, Shane (November 2001). "Kracklin' Kirby: Tracing the advent of Kirby Krackle". Jack Kirby Collector. No. 33. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ Mendryk, Harry (September 3, 2011). "Evolution of Kirby Krackle". Jack Kirby Museum: "Simon and Kirby". Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-31335-747-3. Archivedfrom the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-29274-252-9.

- ISBN 978-0313399237.

- ISBN 978-1605490786.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, pp. 144–171.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, p. 58.

- ISBN 1893905020,

... it's so powerful in pencil, it's really hard to ink it and really retain the full flavour of the pencils. I think a lot of really good inkers have not been able to do that

- ISBN 1893905020,

I was totally awestruck by the magnificent penciling ... no one inker could improve on Jack's penciling

- ^ Eisner 2001, p. 199.

- ^ Eisner 2001, p. 213.

- ^ Eisner 2001, p. 209.

- ^ a b Interview, The Nostalgia Journal #30–1, November 1976 – December 1976, reprinted in George 2002, p. 10

- ^ Mendryk, Harry (April 7, 2007). "Jack Kirby's Austere Inking, Chapter 1, Introduction". Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Roy, ed. (2017). "The Retrospective Stan Lee". Alter Ego (150). TwoMorrows Publishing: 13.

- ^ Morrow, p. 90

- ^ Hatfield & Saunders 2015, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Hatfield & Saunders 2015, p. 28.

- ^ a b Hatfield & Saunders 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Hatfield & Saunders 2015, pp. 149–157.

- The Hammer Museum. November 20, 2005. Archivedfrom the original on June 9, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby". California State University, Northridge. July 2015. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Take "A Jack Kirby Odyssey" in NYC May 11–13!". Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center. April 19, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ISBN 1893905004.

- ^ "Jack Kirby: The House That Jack Built". Paul Gravett. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Jack Kirby". Heritage Auctions. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ Gold, Glen (April 1998), "The Stolen Art", Jack Kirby Collector, no. 19, archived from the original on August 1, 2018, retrieved May 31, 2018

- ^ Hatfield 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Jack Kirby's Galactic Bounty Hunters Archived July 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (February 13, 2008). "Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure #1 Review". IGN. Archived from the original on August 2, 2014.

- ^ Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016.

- ^ Biggers, Cliff (July 2010). "Kirby Genesis: A Testament to the King's Talent". Comic Shop News. No. 1206.

- ^ "Alex Ross & Kurt Busiek Team For Dynamite's Kirby: Genesis". Dynamite Entertainment press release via Newsarama. July 12, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Marvel Worldwide, Inc., Marvel Characters, Inc. and MVL Rights, LLC, against Lisa R. Kirby, Barbara J. Kirby, Neal L. Kirby and Susan M. Kirby, 777 F.Supp.2d 720 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).

- ^ Fritz, Ben (September 21, 2009). "Heirs File Claims to Marvel Heroes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2010.

- ^ Kit, Borys and Matthew Belloni (September 21, 2009). "Kirby Heirs Seeking Bigger Chunk of Marvel Universe". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Melrose, Kevin (January 8, 2010). "Marvel Sues to Invalidate Copyright Claims by Jack Kirby's Heirs". Robot 6. Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010.

- ^ "Marvel Sues for Rights to Superheroes". Associated Press via The Hollywood Reporter. January 8, 2010. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (December 21, 2010). "It's on! Kirby estate sues Marvel; copyrights to Iron Man, Spider-Man at stake". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (July 28, 2011). "Marvel Wins Summary Judgments In Jack Kirby Estate Rights Lawsuits". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011.

- ^ Marvel Characters Inc. v. Kirby, 726 F.3d 119 (2d. Cir. 2013).

- ^ Patten, Dominic (April 2, 2014). "Marvel & Disney Rights Case For Supreme Court To Decide Says Jack Kirby Estate". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014.

- ^ "Kirby v. Marvel Characters, Inc". SCOTUSblog. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (September 26, 2014). "Marvel & Jack Kirby Heirs Settle Legal Battle Ahead Of Supreme Court Showdown". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014.

- ^ Frankel, Alison (September 29, 2014). "Marvel settlement with Kirby leaves freelancers' rights in doubt". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

- ^ Carlin 2005, p. 267.

- ^ Lalumière, Claude (January 2001). "Where There Is Icing". (book review), JanuaryMagazine.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010.

- ^ Lovece, Frank (February 26, 1987). "Aliens Arrives on Video this Week". United Media newspaper syndicate. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ a b ""Postal Service Previews 2007 Commemorative Stamp Program" (October 25, 2006 press release)". USPS.com. October 25, 2006. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Bruce Timm in Khoury, George; Khoury, Pedro III (October 1998). "Bruce Timm Interviewed". Jack Kirby Collector. No. 21. TwoMorrows Publishing. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Berkwits, Jeff (January 28, 2002). "Requiem for Jack Kirby: Gregg Bendian sketches memorable musical scenes from Jack Kirby's legendary comic-book images". Science Fiction Weekly (SciFi.com). Archived from the original on February 11, 2003.

- ISBN 978-1893905610.

- ^ Fogel, Rich and Timm, Bruce (writers); Riba, Dan (director) (February 14, 1998). "Apokolips ... Now!, Part 2". Superman: The Animated Series. Season 2. Episode 39. The WB.

- ^ "Marvel Comics". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2018. Excludes movies starring Blade, Daredevil, Deadpool, Doctor Strange, Elektra, Ghost Rider, Guardians of the Galaxy, Howard the Duck, the Punisher, and Wolverine solo.

- ^ "The King & the Worst". YouTube. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Toronto #4: And the Winner Is." RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Webster, Andy (June 22, 2014). "The Amazing Adventures of Pencil Man". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-49928-849-0.

- )

- ^ "DC Unveils its 'Kirby One-Shot' Creators". ICv2. May 23, 2017. Archived from the original on June 9, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ "DThe Supreme Writer: Alan Moore Interviewed by George Khoury, From Jack Kirby Collector #30". Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Mack, Mike (May 5, 2021). "Countdown to Avengers Campus: The Kirby Krackle". laughingplace.com. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ a b "1967 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "1963 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "1964 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "1965 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "1966 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ a b "1968 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

Mark Hanerfeld originally listed Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. as the winner, but then discovered he had counted separately votes for 'Fantastic Four by Jack Kirby' (42 votes), 'Fantastic Four by Stan Lee', and 'Fantastic Four by Jack Kirby & Stan Lee', which would have given Fantastic Four a total of more than 45 votes and thus the victory.

- ^ "1971 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "Inkpot Award Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012.

- ^ "1974 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "Will Eisner Comic Industry Award: Summary of Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- San Diego Comic-Con International. 2014. Archivedfrom the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ^ "1998 Harvey Award Nominees and Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "1998 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (July 16, 2017). "Jack Kirby to Be Named 'Disney Legend' at D23 Expo in July". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ Olbrich, Dave (December 17, 2008). "The End of the Jack Kirby Comics Industry Awards: A Lesson in Honesty". Funny Book Fanatic (Dave Olbrich official blog). Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ "Eisner Awards History," Archived August 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine San Diego Comic-Con International official website. Accessed May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Newswatch: Kirby Awards End In Controversy", The Comics Journal #122 (June 1988), pp. 19–20

- ^ "Bill Finger Award Recipients". Comics Continuum. Archived from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Exhibitions: Masters of American Comics". The Jewish Museum. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (October 13, 2006). "See You in the Funny Papers". (art review), The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012.

- ^ "51985 Kirby (2001 SA116)". International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center. n.d. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018. Additional on February 6, 2018.

- ^ "Kirby". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. NASA. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

Bibliography

- Carlin, John, ed. (2005). Masters of American comics : [this catalogue was published in conjunction with "Masters of American comics", an exhibition jointly organized by the Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles] With contributions by Stanley Crouch (illustrated ed.). New Haven [u.a.]: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-30011-317-4.

- Eisner, Will (2001). Will Eisner's shop talk (1st ed.). Milwaukie, Or.: Dark Horse Comics. ISBN 978-1-56971-536-9.

- Evanier, Mark (2008). Kirby: King of Comics. New York, New York: ISBN 978-0-8109-9447-8.

- George, Milo, ed. (2002). The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-1-56097-466-6.

- Hatfield, Charles (2012). Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-61703-178-6.

- Hatfield, Charles; Saunders, Brian, eds. (September 2015). Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby : [this catalogue was published in conjunction with "Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby", an exhibition organized by California State University, Northridge, With contributions by various essayists]. Northridge, California: IDW Publishing & California State University, Northridge. ISBN 978-1-63140-542-6.

- ISBN 978-0-465-03657-8.

- Ro, Ronin (2004). Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution. New York, New York: ISBN 978-1-58234-345-7.

- ISBN 978-1-61377-197-6.

Further reading

- Scioli, Tom (2020). Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics. California; New York: Ten Speed Press. OCLC 1122804040.

- Wyman, Ray (1993). The Art of Jack Kirby. Orange, Calif.: Blue Rose Press. OCLC 28128313.

External links

- The Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center

- Jack Kirby at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Jack Kirby at IMDb

- Jack Kirby at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Jack Kirby Archived February 12, 2022, at the Wayback Machine at Mike's Amazing World of Comics

- Evanier, Mark. "The Jack F.A.Q." News From ME. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014.

- Mitchell, Elvis (August 27, 2003). "Jack Kirby Heroes Thrive in Comic Books and Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013.

- Christiansen, Jeff. "Creations of Jack Kirby". Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013.