Jain schools and branches

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Jainism is an Indian religion which is traditionally believed to be propagated by twenty-four spiritual teachers known as tirthankara. Broadly, Jainism is divided into two major schools of thought, Digambara and Śvetāmbara. These are further divided into different sub-sects and traditions. While there are differences in practices, the core philosophy and main principles of each sect is the same.

Schism

Traditionally, the original doctrine of Jainism was contained in scriptures called Purva. There were fourteen Purva. These are believed to have originated from

According to Digambara tradition,

Early Jain images from Mathura depict Digambara iconography until late fifth century A.D. where Svetambara iconography starts appearing.[9]

Differences

Other than rejecting or accepting different ancient Jain texts, Digambaras and Śvetāmbara differ in other significant ways such as:

- Śvetāmbaras trace their practices and dress code to the teachings of Parshvanatha, the 23rd tirthankara, which they believe taught only Four restraints (a claim, scholars say are confirmed by the ancient Buddhist texts that discuss Jain monastic life). However, Śvetāmbara monks also follow Five restraints as Mahāvīra taught. Mahāvīra taught Five vows, which both the sects follow.[10][11][12] The Digambara sect disagrees with the Śvetāmbara interpretations,[13] and reject the theory of difference in Parshvanatha and Mahāvīra's teachings.[11]

- Digambaras believe that both Parshvanatha and Mahāvīra remained unmarried, whereas Śvetāmbara believe the 23rd and 24th did indeed marry. According to the Śvetāmbara version, Parshva married Prabhavati,[14] and Mahāvīra married Yashoda who bore him a daughter named Priyadarshana.[15][16] The two sects also differ on the origin of Trishala, Mahāvīra's mother,[15] as well as the details of Tirthankara's biographies such as how many auspicious dreams their mothers had when they were in the wombs.[17]

- Digambara believe Rishabha, Vasupujya and Neminatha were the three tirthankaras who reached omniscience while in sitting posture and other tirthankaras were in standing ascetic posture. In contrast, Śvetāmbaras believe it was Rishabha, Nemi and Mahāvīra who were the three in sitting posture.[18]

- Digambara iconography are plain, Śvetāmbara icons are decorated and colored to be more lifelike.[19]

- According to Śvetāmbara Jain texts, from Kalpasūtras onwards, its monastic community has had more sadhvis than sadhus (female than male mendicants). In Tapa Gacch of the modern era, the ratio of sadhvis to sadhus (nuns to monks) is about 3.5 to 1.[20] In contrast to Śvetāmbara, the Digambara sect monastic community has been predominantly male.[21]

- In the Digambara tradition, a male human being is considered closest to the apex with the potential to achieve his soul's liberation from rebirths through asceticism. Women must gain karmic merit, to be reborn as man, and only then can they achieve spiritual liberation in the Digambara sect of Jainism.[22][23] The Śvetāmbaras disagree with the Digambaras, believing that women can also achieve liberation from Saṃsāra through ascetic practices.[23][24]

- The Śvetāmbaras state the 19th Tirthankara

Digambara

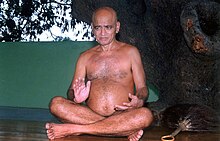

Digambara (sky-clad) is one of the two main sects of

Digambar tradition has two main monastic orders

Monastic orders

Mula Sangh is an ancient monastic order. Mula literally means root or original.[37] The great Acharya Kundakunda is associated with Mula Sangh. The oldest known mention of Mula Sangh is from 430 CE. Mula Sangh was divided into a few branches. According to Shrutavatara and Nitisar of

Kashtha Sangha was a

The

The Taran Panth was founded by Taran Svami in Bundelkhand in 1505.[44] They do not believe in idol worshiping. Instead, the taranapantha community prays to the scriptures written by Taran Swami. Taran Svami is also referred to as Taran Taran, the one who can help the swimmers to the other side, i.e. towards

Svetambara

The Śvetāmbara (white-clad) is one of the two main sects of

Both of the major Jain traditions evolved into sub-traditions over time. For example, the devotional worship traditions of Śvetāmbara are referred to as

Śvētāmbaras who are not Sthānakavāsins are called

- Murtipujaka Svetambara monastic orders

The monks of Murtipujaka sect are divided into six orders or Gaccha. These are:[50]

- Kharatara Gaccha (1023 CE)

- Ancala Gaccha (1156 CE)

- Tristutik Gaccha(1193 CE)

- Tapa Gaccha (1228 CE)

- Vimala Gaccha (1495 CE)

- Parsvacandra Gaccha (1515 CE)

Kharatara Gaccha is one of

Tristutik Gaccha was a

Tapa Gaccha is the largest

A major dispute was initiated by Lonka Shaha, who started a movement opposed to idol worship in 1476.

Terapanth is another reformist religious sect under

About the 18th century, the Śvetāmbara and Digambara traditions saw an emergence of separate Terapanthi movements.[49][59][60] Śvetāmbara Terapanth was started by Acharya Bhikshu in 18th century. In Terapanth there is only one Acharya, which is a unique feature of it.[61]

Others

Raj Bhakta Marg or Kavi Panth or Shrimadia are founded on teachings of

Yapaniya was a Jain order in western Karnataka which is now extinct. The first inscription that mentions them by Mrigesavarman (AD 475–490) a

References

Citations

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Clarke & Beyer 2009, p. 326.

- ^ a b c Winternitz 1993, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 383.

- ^ Winternitz 1993, p. 417.

- ^ Winternitz 1993, p. 455.

- ^ Vyas 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2007, p. 211.

- ^ a b Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Jaini 2000, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 12.

- ^ a b Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Dalal 2010a, p. 167.

- ^ Cort 2001a, p. 47.

- ^ Flügel 2006, pp. 314–331, 353–361.

- ^ Long 2013, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Harvey 2016, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 55–59.

- ^ Vallely 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 23.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 444.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2007, p. 134.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 313.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 314.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 316.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 524.

- ^ a b John E. Cort (2002). "A Tale of Two Cities: On the Origins of Digambara Sectarianism in North India". In L. A. Babb; V. Joshi; M. W. Meister (eds.). Multiple Histories: Culture and Society in the Study of Rajasthan. Jaipur: Rawat. pp. 39–83.

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 48–59.

- ^ Jain Dharma, Kailash Chandra Siddhanta Shastri, 1985.

- ^ "Muni Sabhachandra Avam Unka Padmapuran" (PDF). Idjo.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "(International Digamber Jain Organization)". IDJO.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "History of the Birth of Shree Narsingpura Community". Narsingpura Digambar Jain Samaj. Ndjains.org. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009.

- ^ Sangave 2001, pp. 133–143

- ^ "The Illuminator of the Path of Liberation By Acharyakalp Pt. Todamalji, Jaipur". Atmadharma.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Taranpanthis". Philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Smarika, Sarva Dharma Sammelan, 1974, Taran Taran Samaj, Jabalpur

- ^ "Books I have Loved". Osho.nl. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Quintanilla 2007, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Jaini & Goldman 2018, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Dalal 2010a, p. 341.

- ^ a b "Sthanakavasi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017.

- ^ Flügel 2006, p. 317.

- ^ a b c "Overview of world religions-Jainism-Kharatara Gaccha". Philtar.ac.uk. Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Glasenapp 1999, p. 389.

- ^ Stevenson, S.: Heart of Jainism, p. 19

- ^ Madrecha, Adarsh (21 August 2012). "Thane Jain Yuva Group: United pratikraman organised". Thanejain.blogspot.in. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Dundas, p. 254

- ^ Shashi, p. 945

- ^ Vallely, p. 59

- ^ Singh, p. 5184

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 41, 60.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 155–157, 249–250, 254–259.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 249.

- ^ Petit, Jérôme (2016). "Rājacandra". Jainpedia. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Flügel 2005.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Prasad S, Shyam (11 August 2022). "Karnataka: Inscription may unlock Jain heritage secrets". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- Gulabchand Hirachand Doshi, Jaina Saṁskṛti Saṁrakshaka Sangha

- ^ Jaini 1991, p. 45.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-203-87212-3

- Cort, John E. (2001a), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513234-2

- ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Flügel, Peter (2005). "Present Lord: Simandhara Svami and the Akram Vijnan Movement" (PDF). In King, Anna S.; Brockington, John (eds.). The Intimate Other: Love Divine in the Indic Religions. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 194–243. ISBN 9788125028017.

- Flügel, Peter (2006), Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-23552-0

- Glasenapp, Helmuth Von (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Harvey, Graham (2016), Religions in Focus: New Approaches to Tradition and Contemporary Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-93690-8

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- ISBN 0-520-06820-3

- Jaini, Padmanabh S.; Goldman, Robert (2018), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-30296-9

- Jaini, Padmanabh S., ed. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies (First ed.), Delhi: ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9

- Long, Jeffery D. (2013), Jainism: An Introduction, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85771-392-6

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007), History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE, BRILL, ISBN 9789004155374

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. I, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2

- ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Singh, Ram Bhushan Prasad (2008). Jainism In Early Medieval Karnataka. ISBN 978-81-208-3323-4.

- Vallely, Anne (2002), Guardians of the Transcendent: An Ethnology of a Jain Ascetic Community, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-8415-6

- Vyas, Dr. R. T., ed. (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects, The Director, Oriental Institute, on behalf of the Registrar, M.S. University of Baroda, Vadodara, ISBN 81-7017-316-7

- ISBN 81-208-0265-9