James Webb Space Telescope

Astronomy | |

| Operator | STScI (NASA)[1] / ESA / CSA |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 2021-130A |

| SATCAT no. | 50463[2] |

| Website | Official website webbtelescope |

| Mission duration | |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | |

| Launch mass | 6,500 kg (14,300 lb)[5] |

| Dimensions | 21.197 m × 14.162 m (69.54 ft × 46.46 ft),[6] sunshield |

| Power | 2 kW |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 25 December 2021, 12:20 UTC[5] |

| Rocket | Ariane 5 ECA (VA256) |

| Launch site | Centre Spatial Guyanais, ELA-3 |

| Contractor | Arianespace |

| Entered service | July 12, 2022 |

| Orbital parameters | |

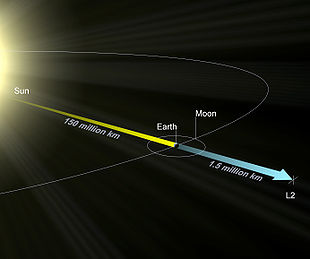

| Reference system | Sun–Earth L2 orbit |

| Regime | Halo orbit |

| Periapsis altitude | 250,000 km (160,000 mi)[7] |

| Apoapsis altitude | 832,000 km (517,000 mi)[7] |

| Period | 6 months |

| Main telescope | |

| Type | Korsch telescope |

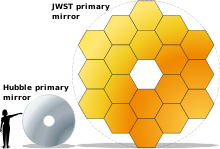

| Diameter | 6.5 m (21 ft) |

| Focal length | 131.4 m (431 ft) |

| Focal ratio | f/20.2 |

| Collecting area | 25.4 m2 (273 sq ft)[8] |

| Wavelengths | 0.6–28.3 μm (orange to mid-infrared) |

| Transponders | |

| Band |

|

| Bandwidth |

|

| Instruments | |

| Elements | |

| |

James Webb Space Telescope mission logo | |

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is a

The Webb was launched on 25 December 2021 on an

The U.S.

The

programs.Webb's

Initial designs for the telescope, then named the Next Generation Space Telescope, began in 1996. Two concept studies were commissioned in 1999, for a potential launch in 2007 and a US$1 billion budget. The program was plagued with enormous cost overruns and delays. A major redesign was accomplished in 2005, with construction completed in 2016, followed by years of exhaustive testing, at a total cost of US$10 billion.

Features

The mass of the James Webb Space Telescope is about half that of the

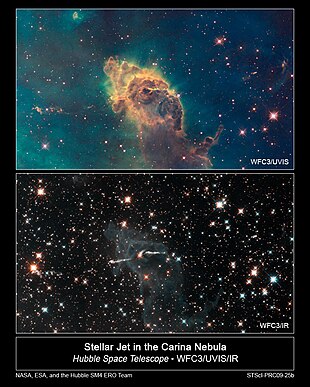

Webb is designed primarily for

The design emphasizes the near to mid-infrared for several reasons:

- high-redshift (very early and distant) objects have their visible emissions shifted into the infrared, and therefore their light can be observed only via infrared astronomy;[15]

- infrared light passes more easily through dust clouds than visible light;[15]

- colder objects such as debris disks and planets emit most strongly in the infrared;

- these infrared bands are difficult to study from the ground or by existing space telescopes such as Hubble.

Ground-based telescopes must look through Earth's atmosphere, which is opaque in many infrared bands (see figure at right). Even where the atmosphere is transparent, many of the target chemical compounds, such as water, carbon dioxide, and methane, also exist in the Earth's atmosphere, vastly complicating analysis. Existing space telescopes such as Hubble cannot study these bands since their mirrors are insufficiently cool (the Hubble mirror is maintained at about 15 °C [288 K; 59 °F]) which means that the telescope itself radiates strongly in the relevant infrared bands.[24]

Webb can also observe objects in the

-

Three-quarter view of the top

-

Bottom (Sun-facing side)

Location and orbit

Webb operates in a

Sunshield protection

To make observations in the infrared spectrum, Webb must be kept under 50 K (−223.2 °C; −369.7 °F); otherwise, infrared radiation from the telescope itself would overwhelm its instruments. Its large sunshield blocks light and heat from the Sun, Earth, and Moon, and its position near the Sun–Earth L2 keeps all three bodies on the same side of the spacecraft at all times.[32] Its halo orbit around the L2 point avoids the shadow of the Earth and Moon, maintaining a constant environment for the sunshield and solar arrays.[29] The resulting stable temperature for the structures on the dark side is critical to maintaining precise alignment of the primary mirror segments.[30]

The five-layer sunshield, each layer as thin as a human hair,

The sunshield was designed to be folded twelve times so that it would fit within the Ariane 5 rocket's payload fairing, which is 4.57 m (15.0 ft) in diameter, and 16.19 m (53.1 ft) long. The shield's fully deployed dimensions were planned as 14.162 m × 21.197 m (46.46 ft × 69.54 ft).[35]

Keeping within the shadow of the sunshield limits the field of regard of Webb at any given time. The telescope can see 40 percent of the sky from any one position, but can see all of the sky over a period of six months.[36]

Optics

Webb's

Webb's optical design is a

Scientific instruments

The Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM) is a framework that provides electrical power, computing resources, cooling capability as well as structural stability to the Webb telescope. It is made with bonded graphite-epoxy composite attached to the underside of Webb's telescope structure. The ISIM holds the four science instruments and a guide camera.[43]

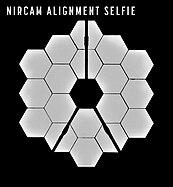

- NIRCam (Near Infrared Camera) is an infrared imager which has spectral coverage ranging from the edge of the visible (0.6 μm) through to the near infrared (5 μm).[44][45] There are 10 sensors each of 4 megapixels. NIRCam serves as the observatory's wavefront sensor, which is required for wavefront sensing and control activities, used to align and focus the main mirror segments. NIRCam was built by a team led by the University of Arizona, with principal investigator Marcia J. Rieke.[46]

- ESTEC in Noordwijk, Netherlands. The leading development team includes members from Airbus Defence and Space, Ottobrunn and Friedrichshafen, Germany, and the Goddard Space Flight Center; with Pierre Ferruit (École normale supérieure de Lyon) as NIRSpec project scientist. The NIRSpec design provides three observing modes: a low-resolution mode using a prism, an R~1000 multi-object mode, and an R~2700 integral field unit or long-slit spectroscopy mode. Switching of the modes is done by operating a wavelength preselection mechanism called the Filter Wheel Assembly, and selecting a corresponding dispersive element (prism or grating) using the Grating Wheel Assembly mechanism. Both mechanisms are based on the successful ISOPHOT wheel mechanisms of the Infrared Space Observatory. The multi-object mode relies on a complex micro-shutter mechanism to allow for simultaneous observations of hundreds of individual objects anywhere in NIRSpec's field of view. There are two sensors, each of 4 megapixels.[47]

- mid-infrared camera and an imaging spectrometer.[50] MIRI was developed as a collaboration between NASA and a consortium of European countries, and is led by George Rieke (University of Arizona) and Gillian Wright (UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Edinburgh, Scotland).[46] The temperature of the MIRI must not exceed 6 K (−267 °C; −449 °F): a helium gas mechanical cooler sited on the warm side of the environmental shield provides this cooling.[51]

- FGS/NIRISS (Fine Guidance Sensor and Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph), led by the Canadian Space Agency under project scientist John Hutchings (Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre), is used to stabilize the line-of-sight of the observatory during science observations. Measurements by the FGS are used both to control the overall orientation of the spacecraft and to drive the fine steering mirror for image stabilization. The Canadian Space Agency also provided a Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) module for astronomical imaging and spectroscopy in the 0.8 to 5 μm wavelength range, led by principal investigator René Doyon[52] at the Université de Montréal.[46] Although they are often referred together as a unit, the NIRISS and FGS serve entirely different purposes, with one being a scientific instrument and the other being a part of the observatory's support infrastructure.[53]

NIRCam and MIRI feature starlight-blocking

Spacecraft bus

The

The structure of the spacecraft bus has a mass of 350 kg (770 lb), and must support the 6,200 kg (13,700 lb) space telescope. It is made primarily of graphite composite material.[57] The assembly was completed in California in 2015. It was integrated with the rest of the space telescope leading to its 2021 launch. The spacecraft bus can rotate the telescope with a pointing precision of one arcsecond, and isolates vibration to two milliarcseconds.[58]

Webb has two pairs of rocket engines (one pair for redundancy) to make course corrections on the way to L2 and for station keeping – maintaining the correct position in the halo orbit. Eight smaller thrusters are used for attitude control – the correct pointing of the spacecraft.[59] The engines use hydrazine fuel (159 liters or 42 U.S. gallons at launch) and dinitrogen tetroxide as oxidizer (79.5 liters or 21.0 U.S. gallons at launch).[60]

Servicing

Webb is not intended to be serviced in space. A crewed mission to repair or upgrade the observatory, as was done for Hubble, would not be possible,[61] and according to NASA Associate Administrator Thomas Zurbuchen, despite best efforts, an uncrewed remote mission was found to be beyond available technology at the time Webb was designed.[62] During the long Webb testing period, NASA officials referred to the idea of a servicing mission, but no plans were announced.[63][64] Since the successful launch, NASA has stated that nevertheless limited accommodation was made to facilitate future servicing missions. These accommodations included precise guidance markers in the form of crosses on the surface of Webb, for use by remote servicing missions, as well as refillable fuel tanks, removable heat protectors, and accessible attachment points.[65][62]

Software

Ilana Dashevsky and Vicki Balzano write that Webb uses a modified version of JavaScript, called Nombas ScriptEase 5.00e, for its operations; it follows the ECMAScript standard and "allows for a modular design flow, where on-board scripts call lower-level scripts that are defined as functions". "The JWST science operations will be driven by ASCII (instead of binary command blocks) on-board scripts, written in a customized version of JavaScript. The script interpreter is run by the flight software, which is written in the programming language C++. The flight software operates the spacecraft and the science instruments."[66][67]

Comparison with other telescopes

The desire for a large infrared space telescope traces back decades. In the United States, the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (later called the Spitzer Space Telescope) was planned while the Space Shuttle was in development, and the potential for infrared astronomy was acknowledged at that time.[68] Unlike ground telescopes, space observatories are free from atmospheric absorption of infrared light. Space observatories opened a "new sky" for astronomers.

However, there is a challenge involved in the design of infrared telescopes: they need to stay extremely cold, and the longer the wavelength of infrared, the colder they need to be. If not, the background heat of the device itself overwhelms the detectors, making it effectively blind. This can be overcome by careful design. One method is to put the key instruments in a dewar with an extremely cold substance, such as liquid helium. The coolant will slowly vaporize, limiting the lifetime of the instrument from as short as a few months to a few years at most.[24]

It is also possible to maintain a low temperature by designing the spacecraft to enable near-infrared observations without a supply of coolant, as with the extended missions of the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, which operated at reduced capacity after coolant depletion. Another example is Hubble's Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) instrument, which started out using a block of nitrogen ice that depleted after a couple of years, but was then replaced during the STS-109 servicing mission with a cryocooler that worked continuously. The Webb Space Telescope is designed to cool itself without a dewar, using a combination of sunshields and radiators, with the mid-infrared instrument using an additional cryocooler.[69]

| Name | Launch year | Wavelength (μm) |

Aperture (m) |

Cooling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Spacelab Infrared Telescope (IRT)

|

1985 | 1.7–118 | 0.15 | Helium |

| Infrared Space Observatory (ISO)[71] | 1995 | 2.5–240 | 0.60 | Helium |

| Hubble Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) | 1997 | 0.115–1.03 | 2.4 | Passive |

| Hubble Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) | 1997 | 0.8–2.4 | 2.4 | Nitrogen, later cryocooler |

| Spitzer Space Telescope | 2003 | 3–180 | 0.85 | Helium |

| Hubble Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) | 2009 | 0.2–1.7 | 2.4 | Passive and thermo-electric[72] |

| Herschel Space Observatory | 2009 | 55–672 | 3.5 | Helium |

| James Webb Space Telescope | 2021 | 0.6–28.5 | 6.5 | Passive and cryocooler (MIRI) |

Webb's delays and cost increases have been compared to those of its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope. When Hubble formally started in 1972, it had an estimated development cost of US$300 million (equivalent to $2,185,203,000 in 2023), but by the time it was sent into orbit in 1990, the cost was about four times that. In addition, new instruments and servicing missions increased the cost to at least US$9 billion by 2006[73] (equivalent to $13,602,509,000 in 2023).

Development history

Background (development to 2003)

| Year | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 1996 | Next Generation Space Telescope project first proposed (mirror size: 8 m) |

| 2001 | NEXUS Space Telescope, a precursor to the Next Generation Space Telescope, cancelled[74] |

| 2002 | Proposed project renamed James Webb Space Telescope, (mirror size reduced to 6 m) |

| 2003 | Northrop Grumman awarded contract to build telescope |

| 2007 | Memorandum of Understanding signed between NASA and ESA[75]

|

| 2010 | Mission Critical Design Review (MCDR) passed |

| 2011 | Proposed cancellation |

| 2016 | Final assembly completed |

| 25 December 2021 | Launch |

Discussions of a Hubble follow-on started in the 1980s, but serious planning began in the early 1990s.

Correcting the

The HST & Beyond Committee was formed in 1994 "to study possible missions and programs for optical-ultraviolet astronomy in space for the first decades of the 21st century."[81] Emboldened by HST's success, its 1996 report explored the concept of a larger and much colder, infrared-sensitive telescope that could reach back in cosmic time to the birth of the first galaxies. This high-priority science goal was beyond the HST's capability because, as a warm telescope, it is blinded by infrared emission from its own optical system. In addition to recommendations to extend the HST mission to 2005 and to develop technologies for finding planets around other stars, NASA embraced the chief recommendation of HST & Beyond[82] for a large, cold space telescope (radiatively cooled far below 0 °C), and began the planning process for the future Webb telescope.

Preparation for the 2000

As hoped, the NGST received the highest ranking in the 2000 Decadal Survey.[84]

An

The mid-1990s era of "faster, better, cheaper" produced the NGST concept, with an 8 m (26 ft) aperture to be flown to L2, roughly estimated to cost US$500 million.[85] In 1997, NASA worked with the Goddard Space Flight Center,[86] Ball Aerospace & Technologies,[87] and TRW[88] to conduct technical requirement and cost studies of the three different concepts, and in 1999 selected Lockheed Martin[89] and TRW for preliminary concept studies.[90] Launch was at that time planned for 2007, but the launch date was pushed back many times (see table further down).

In 2002, the project was renamed after NASA's second administrator (1961–1968), James E. Webb (1906–1992).[91] Webb led the agency during the Apollo program and established scientific research as a core NASA activity.[92]

In 2003, NASA awarded TRW the US$824.8 million prime contract for Webb. The design called for a de-scoped 6.1 m (20 ft) primary mirror and a launch date of 2010.[93] Later that year, TRW was acquired by Northrop Grumman in a hostile bid and became Northrop Grumman Space Technology.[90]

Early development and replanning (2003–2007)

Development was managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with John C. Mather as its project scientist. The primary contractor was Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems, responsible for developing and building the spacecraft element, which included the satellite bus, sunshield, Deployable Tower Assembly (DTA) which connects the Optical Telescope Element to the spacecraft bus, and the Mid Boom Assembly (MBA) which helps to deploy the large sunshields on orbit,[94] while Ball Aerospace & Technologies was subcontracted to develop and build the OTE itself, and the Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM).[43]

Cost growth revealed in spring 2005 led to an August 2005 re-planning.[95] The primary technical outcomes of the re-planning were significant changes in the integration and test plans, a 22-month launch delay (from 2011 to 2013), and elimination of system-level testing for observatory modes at wavelengths shorter than 1.7 μm. Other major features of the observatory were unchanged. Following the re-planning, the project was independently reviewed in April 2006.[citation needed]

In the 2005 re-plan, the life-cycle cost of the project was estimated at US$4.5 billion. This comprised approximately US$3.5 billion for design, development, launch and commissioning, and approximately US$1.0 billion for ten years of operations.[95] The ESA agreed in 2004 to contributing about €300 million, including the launch.[96] The Canadian Space Agency pledged CA$39 million in 2007[97] and in 2012 delivered its contributions in equipment to point the telescope and detect atmospheric conditions on distant planets.[98]

Detailed design and construction (2007–2021)

In January 2007, nine of the ten technology development items in the project successfully passed a Non-Advocate Review.

In April 2010, the telescope passed the technical portion of its Mission Critical Design Review (MCDR). Passing the MCDR signified the integrated observatory can meet all science and engineering requirements for its mission.[102] The MCDR encompassed all previous design reviews. The project schedule underwent review during the months following the MCDR, in a process called the Independent Comprehensive Review Panel, which led to a re-plan of the mission aiming for a 2015 launch, but as late as 2018. By 2010, cost over-runs were impacting other projects, though Webb itself remained on schedule.[103]

By 2011, the Webb project was in the final design and fabrication phase (Phase C).

Assembly of the hexagonal segments of the primary mirror, which was done via robotic arm, began in November 2015 and was completed on 3 February 2016. The secondary mirror was installed on 3 March 2016.[104][105] Final construction of the Webb telescope was completed in November 2016, after which extensive testing procedures began.[106]

In March 2018, NASA delayed Webb's launch an additional two years to May 2020 after the telescope's sunshield ripped during a practice deployment and the sunshield's cables did not sufficiently tighten. In June 2018, NASA delayed the launch by an additional 10 months to March 2021, based on the assessment of the independent review board convened after the failed March 2018 test deployment.

After construction was completed, Webb underwent final tests at Northrop Grumman's historic Space Park in Redondo Beach, California.[110] A ship carrying the telescope left California on 26 September 2021, passed through the Panama Canal, and arrived in French Guiana on 12 October 2021.[111]

Cost and schedule issues

NASA's lifetime cost for the project is[when?] expected to be US$9.7 billion, of which US$8.8 billion was spent on spacecraft design and development and US$861 million is planned to support five years of mission operations.[112] Representatives from ESA and CSA stated their project contributions amount to approximately €700 million and CA$200 million, respectively.[113]

A study in 1984 by the Space Science Board estimated that to build a next-generation infrared observatory in orbit would cost US$4 billion (US$7B in 2006 dollars, or $10B in 2020 dollars).[73] While this came close to the final cost of Webb, the first NASA design considered in the late 1990s was more modest, aiming for a $1 billion price tag over 10 years of construction. Over time this design expanded, added funding for contingencies, and had scheduling delays.

| Year | Planned launch |

Budget plan (billion USD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2007[114] | 1[73] |

| 2000 | 2009[48] | 1.8[73] |

| 2002 | 2010[115] | 2.5[73] |

| 2003 | 2011[116] | 2.5[73] |

| 2005 | 2013 | 3[117] |

| 2006 | 2014 | 4.5[118] |

| 2008: Preliminary Design Review | ||

| 2008 | 2014 | 5.1[119] |

| 2010: Critical Design Review | ||

| 2010 | 2015 to 2016 | 6.5[120] |

| 2011 | 2018 | 8.7[121] |

| 2017 | 2019[122] | 8.8 |

| 2018 | 2020[123] | ≥8.8 |

| 2019 | March 2021[124] | 9.66 |

| 2021 | Dec 2021[125] | 9.70 |

By 2008, when the project entered preliminary design review and was formally confirmed for construction, over US$1 billion had already been spent on developing the telescope, and the total budget was estimated at about US$5 billion (equivalent to $7.8 billion in 2023).[126] In summer 2010, the mission passed its Critical Design Review (CDR) with excellent grades on all technical matters, but schedule and cost slips at that time prompted Maryland U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski to call for external review of the project. The Independent Comprehensive Review Panel (ICRP) chaired by J. Casani (JPL) found that the earliest possible launch date was in late 2015 at an extra cost of US$1.5 billion (for a total of US$6.5 billion). They also pointed out that this would have required extra funding in FY2011 and FY2012 and that any later launch date would lead to a higher total cost.[120]

On 6 July 2011, the United States House of Representatives' appropriations committee on Commerce, Justice, and Science moved to cancel the James Webb project by proposing an FY2012 budget that removed US$1.9 billion from NASA's overall budget, of which roughly one quarter was for Webb.[127][128][129][130] US$3 billion had been spent and 75% of its hardware was in production.[131] This budget proposal was approved by subcommittee vote the following day. The committee charged that the project was "billions of dollars over budget and plagued by poor management".[127] In response, the American Astronomical Society issued a statement in support of Webb,[132] as did Senator Mikulski.[133] A number of editorials supporting Webb appeared in the international press during 2011 as well.[127][134][135] In November 2011, Congress reversed plans to cancel Webb and instead capped additional funding to complete the project at US$8 billion.[136]

While similar issues had affected other major NASA projects such as the Hubble telescope, some scientists expressed concerns about growing costs and schedule delays for the Webb telescope, worrying that its budget might be competing with those of other space science programs.[137][138] A 2010 Nature article described Webb as "the telescope that ate astronomy".[139] NASA continued to defend the budget and timeline of the program to Congress.[138][140]

In 2018, Gregory L. Robinson was appointed as the new director of the Webb program.[141] Robinson was credited with raising the program's schedule efficiency (how many measures were completed on time) from 50% to 95%.[141] For his role in improving the performance of the Webb program, Robinsons's supervisor, Thomas Zurbuchen, called him "the most effective leader of a mission I have ever seen in the history of NASA."[141] In July 2022, after Webb's commissioning process was complete and it began transmitting its first data, Robinson retired following a 33-year career at NASA.[142]

On 27 March 2018, NASA pushed back the launch to May 2020 or later,[123] with a final cost estimate to come after a new launch window was determined with the European Space Agency (ESA).[143][144][145] In 2019, its mission cost cap was increased by US$800 million.[146] After launch windows were paused in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic,[147] Webb was launched at the end of 2021, with a total cost of just under US$10 billion.

No single area drove the cost. For future large telescopes, there are five major areas critical to controlling overall cost:[148]

- System Complexity

- Critical path and overhead

- Verification challenges

- Programmatic constraints

- Early integration and test considerations

Partnership

NASA, ESA and CSA have collaborated on the telescope since 1996. ESA's participation in construction and launch was approved by its members in 2003 and an agreement was signed between ESA and NASA in 2007. In exchange for full partnership, representation and access to the observatory for its astronomers, ESA is providing the NIRSpec instrument, the Optical Bench Assembly of the MIRI instrument, an Ariane 5 ECA launcher, and manpower to support operations.[96][149] The CSA provided the Fine Guidance Sensor and the Near-Infrared Imager Slitless Spectrograph and manpower to support operations.[150]

Several thousand scientists, engineers, and technicians spanning 15 countries have contributed to the build, test and integration of Webb.[151] A total of 258 companies, government agencies, and academic institutions participated in the pre-launch project; 142 from the United States, 104 from 12 European countries (including 21 from the U.K., 16 from France, 12 from Germany and 7 international),[152] and 12 from Canada.[151] Other countries as NASA partners, such as Australia, were involved in post-launch operation.[153]

Participating countries:

Naming concerns

In 2002, NASA administrator (2001–2004) Sean O'Keefe made the decision to name the telescope after James E. Webb, the administrator of NASA from 1961 to 1968 during the Mercury, Gemini, and much of the Apollo programs.[91][92]

In 2015, concerns were raised around Webb's possible role in the

Mission goals

The James Webb Space Telescope has four key goals:

- to search for light from the first stars and galaxies that formed in the universe after the Big Bang

- to study galaxy formation and evolution

- to understand planet formation

- to study planetary systems and the origins of life[159]

These goals can be accomplished more effectively by observation in near-infrared light rather than light in the visible part of the spectrum. For this reason, Webb's instruments will not measure visible or ultraviolet light like the Hubble Telescope, but will have a much greater capacity to perform infrared astronomy. Webb will be sensitive to a range of wavelengths from 0.6 to 28 μm (corresponding respectively to orange light and deep infrared radiation at about 100 K or −173 °C).

Webb may be used to gather information on the dimming light of star KIC 8462852, which was discovered in 2015, and has some abnormal light-curve properties.[160]

Additionally, it will be able to tell if an exoplanet has methane in its atmosphere, allowing astronomers to determine whether or not the methane is a biosignature.[161][162]

Orbit design

Webb orbits the Sun near the second Lagrange point (L2) of the Sun–Earth system, which is 1,500,000 km (930,000 mi) farther from the Sun than the Earth's orbit, and about four times farther than the Moon's orbit. Normally an object circling the Sun farther out than Earth would take longer than one year to complete its orbit. But near the L2 point, the combined gravitational pull of the Earth and the Sun allow a spacecraft to orbit the Sun in the same time that it takes the Earth. Staying close to Earth allows data rates to be much faster for a given size of antenna.

The telescope circles about the Sun–Earth L2 point in a halo orbit, which is inclined with respect to the ecliptic, has a radius varying between about 250,000 km (160,000 mi) and 832,000 km (517,000 mi), and takes about half a year to complete.[29] Since L2 is just an equilibrium point with no gravitational pull, a halo orbit is not an orbit in the usual sense: the spacecraft is actually in orbit around the Sun, and the halo orbit can be thought of as controlled drifting to remain in the vicinity of the L2 point.[163] This requires some station-keeping: around 2.5 m/s per year[164] from the total ∆v budget of 93 m/s.[165]: 10 Two sets of thrusters constitute the observatory's propulsion system.[166] Because the thrusters are located solely on the Sun-facing side of the observatory, all station-keeping operations are designed to slightly undershoot the required amount of thrust in order to avoid pushing Webb beyond the semi-stable L2 point, a situation which would be unrecoverable. Randy Kimble, the Integration and Test Project Scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, compared the precise station-keeping of Webb to "Sisyphus [...] rolling this rock up the gentle slope near the top of the hill – we never want it to roll over the crest and get away from him".[167]

Infrared astronomy

Webb is the formal successor to the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), and since its primary emphasis is on

The more distant an object is, the younger it appears; its light has taken longer to reach human observers. Because the universe is expanding, as the light travels it becomes red-shifted, and objects at extreme distances are therefore easier to see if viewed in the infrared.[170] Webb's infrared capabilities are expected to let it see back in time to the first galaxies forming just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.[171]

Infrared radiation can pass more freely through regions of

Relatively cool objects (temperatures less than several thousand degrees) emit their radiation primarily in the infrared, as described by Planck's law. As a result, most objects that are cooler than stars are better studied in the infrared.[170] This includes the clouds of the interstellar medium, brown dwarfs, planets both in our own and other solar systems, comets, and Kuiper belt objects that will be observed with the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).[48][171]

Some of the missions in infrared astronomy that impacted Webb development were Spitzer and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP).[172] Spitzer showed the importance of mid-infrared, which is helpful for tasks such as observing dust disks around stars.[172] Also, the WMAP probe showed the universe was "lit up" at redshift 17, further underscoring the importance of the mid-infrared.[172] Both these missions were launched in the early 2000s, in time to influence Webb development.[172]

Ground support and operations

The

The bandwidth and digital throughput of the satellite is designed to operate at 458 gigabits of data per day for the length of the mission (equivalent to a sustained rate of 5.42

The telescope is equipped with a solid-state drive (SSD) with a capacity of 68 GB, used as temporary storage for data collected from its scientific instruments. By the end of the 10-year mission, the usable capacity of the drive is expected to decrease to 60 GB due to the effects of radiation and read/write operations.[176]

Micrometeoroid strike

The C3[c] mirror segment suffered a micrometeoroid strike from a large dust mote-sized particle between 23 and 25 May, the fifth and largest strike since launch, reported 8 June 2022, which required engineers to compensate for the strike using a mirror actuator.[178] Despite the strike, a NASA characterization report states "all JWST observing modes have been reviewed and confirmed to be ready for science use" as of July 10, 2022.[179]

From launch through commissioning

Launch

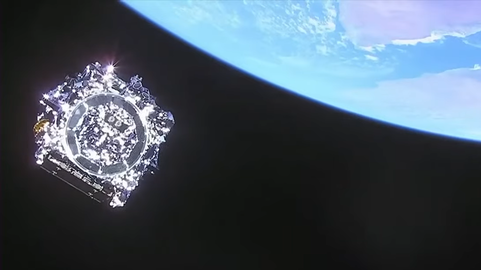

The launch (designated Ariane flight VA256) took place as scheduled at 12:20 UTC on 25 December 2021 on an Ariane 5 rocket that lifted off from the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana.[180][181] The telescope was confirmed to be receiving power, starting a two-week deployment phase of its parts[182] and traveling to its target destination.[183][184][185] The telescope was released from the upper stage 27 minutes 7 seconds after launch, beginning a 30-day adjustment to place the telescope in a Lissajous orbit[186] around the L2 Lagrange point.

The telescope was launched with slightly less speed than needed to reach its final orbit, and slowed down as it travelled away from Earth, in order to reach L2 with only the velocity needed to enter its orbit there. The telescope reached L2 on 24 January 2022. The flight included three planned course corrections to adjust its speed and direction. This is because the observatory could recover from underthrust (going too slowly), but could not recover from overthrust (going too fast) – to protect highly temperature-sensitive instruments, the sunshield must remain between telescope and Sun, so the spacecraft could not turn around or use its thrusters to slow down.[187]

An L2 orbit is unstable, so JWST needs to use propellant to maintain its halo orbit around L2 (known as station-keeping) to prevent the telescope from drifting away from its orbital position.[188] It was designed to carry enough propellant for 10 years,[189] but the precision of the Ariane 5 launch and the first midcourse correction were credited with saving enough onboard fuel that JWST may be able to maintain its orbit for around 20 years instead.[190][191][192] Space.com called the launch "flawless".[193]

-

Diagram of Webb inside Ariane 5

-

Ariane 5 and Webb at the ELA-3 launch pad

-

Ariane 5 containing the James Webb Space Telescope lifting-off from the launch pad

-

Ariane 5 containing Webb moments after lift-off

-

Webb as seen from the ESC-D Cryotechnic upper stage shortly after separation, approximately 29 minutes after launch. Part of the Earth with the Gulf of Aden is visible in the background of the image.[194]

Transit and structural deployment

Webb was released from the rocket upper stage 27 minutes after a flawless launch.[180][195] Starting 31 minutes after launch, and continuing for about 13 days, Webb began the process of deploying its solar array, antenna, sunshield, and mirrors.[196] Nearly all deployment actions are commanded by the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, except for two early automatic steps, solar panel unfolding and communication antenna deployment.[197][198] The mission was designed to give ground controllers flexibility to change or modify the deployment sequence in case of problems.[199]

At 7:50 p.m. EST on 25 December 2021, about 12 hours after launch, the telescope's pair of primary rockets began firing for 65 minutes to make the first of three planned mid-course corrections.[200] On day two, the high gain communication antenna deployed automatically.[199]

On 27 December 2021, at 60 hours after launch, Webb's rockets fired for nine minutes and 27 seconds to make the second of three mid-course corrections for the telescope to arrive at its L2 destination.[201] On 28 December 2021, three days after launch, mission controllers began the multi-day deployment of Webb's all-important sunshield. On 30 December 2021, controllers successfully completed two more steps in unpacking the observatory. First, commands deployed the aft "momentum flap", a device that provides balance against solar pressure on the sunshield, saving fuel by reducing the need for thruster firing to maintain Webb's orientation.[202]

On 31 December 2021, the ground team extended the two telescoping "mid booms" from the left and right sides of the observatory.[203] The left side deployed in 3 hours and 19 minutes; the right side took 3 hours and 42 minutes.[204][203] Commands to separate and tension the membranes followed between 3 and 4 January and were successful.[203] On 5 January 2022, mission control successfully deployed the telescope's secondary mirror, which locked itself into place to a tolerance of about one and a half millimeters.[205]

The last step of structural deployment was to unfold the wings of the primary mirror. Each panel consists of three primary mirror segments and had to be folded to allow the space telescope to be installed in the fairing of the Ariane rocket for the launch of the telescope. On 7 January 2022, NASA deployed and locked in place the port-side wing,[206] and on 8 January, the starboard-side mirror wing. This successfully completed the structural deployment of the observatory.[207][208][209]

On 24 January 2022, at 2:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time,[210] nearly a month after launch, a third and final course correction took place, inserting Webb into its planned halo orbit around the Sun–Earth L2 point.[211][212]

The MIRI instrument has four observing modes – imaging, low-resolution spectroscopy, medium-resolution spectroscopy and coronagraphic imaging. “On Aug. 24, a mechanism that supports medium-resolution spectroscopy (MRS), exhibited what appears to be increased friction during setup for a science observation. This mechanism is a grating wheel that allows scientists to select between short, medium, and longer wavelengths when making observations using the MRS mode,” said NASA in a press statement.[213]

Commissioning and testing

On 12 January 2022, while still in transit, mirror alignment began. The primary mirror segments and secondary mirror were moved away from their protective launch positions. This took about 10 days, because the 132

Mirror alignment requires each of the 18 mirror segments, and the secondary mirror, to be positioned to within 50

- James Webb Space Telescope Mirror alignment animations

-

Segment image identification. 18 mirror segments are moved to determine which segment creates which segment image. After matching the mirror segments to their respective images, the mirrors are tilted to bring all the images near a common point for further analysis.

-

Segment alignment begins by defocusing the segment images by moving the secondary mirror slightly. Mathematical analysis, called phase retrieval, is applied to the defocused images to determine the precise positioning errors of the segments. Adjustments of the segments then result in 18 well-corrected "telescopes". However, the segments still do not work together as a single mirror.

-

Image stacking. To put all of the light in a single place, each segment image must be stacked on top of one another. In the image stacking step, the individual segment images are moved so that they fall precisely at the center of the field to produce one unified image. This process prepares the telescope for coarse phasing.

-

Telescope alignment over instrument fields of view. After fine phasing, the telescope is well aligned at one place in the NIRCam field of view. Next the alignment must be extended to the rest of the instruments.

Mirror alignment was a complex operation split into seven phases, that had been repeatedly rehearsed using a 1:6 scale model of the telescope.[216] Once the mirrors reached 120 K (−153 °C; −244 °F),[217] NIRCam targeted the 6th magnitude star HD 84406 in Ursa Major.[d][219][220] To do this, NIRCam took 1560 images of the sky and used these wide-ranging images to determine where in the sky each segment of the main mirror initially pointed.[221] At first, the individual primary mirror segments were greatly misaligned, so the image contained 18 separate, blurry, images of the star field, each containing an image of the target star. The 18 images of HD 84406 are matched to their respective mirror segments, and the 18 segments are brought into approximate alignment centered on the star ("Segment Image Identification"). Each segment was then individually corrected of its major focusing errors, using a technique called phase retrieval, resulting in 18 separate good quality images from the 18 mirror segments ("Segment Alignment"). The 18 images from each segment, were then moved so they precisely overlap to create a single image ("Image Stacking").[216]

With the mirrors positioned for almost correct images, they had to be fine tuned to their operational accuracy of 50 nanometers, less than one wavelength of the light that will be detected. A technique called dispersed fringe sensing was used to compare images from 20 pairings of mirrors, allowing most of the errors to be corrected ("Coarse Phasing"), and then introduced light defocus to each segment's image, allowing detection and correction of almost all remaining errors ("Fine Phasing"). These two processes were repeated three times, and Fine Phasing will be routinely checked throughout the telescope's operation. After three rounds of Coarse and Fine Phasing, the telescope was well aligned at one place in the NIRCam field of view. Measurements will be made at various points in the captured image, across all instruments, and corrections calculated from the detected variations in intensity, giving a well-aligned outcome across all instruments ("Telescope Alignment Over Instrument Fields of View"). Finally, a last round of Fine Phasing and checks of image quality on all instruments was performed, to ensure that any small residual errors remaining from the previous steps, were corrected ("Iterate Alignment for Final Correction"). The telescope's mirror segments were then aligned and able to capture precise focused images.[216]

In preparation for alignment, NASA announced at 19:28 UTC on 3 February 2022, that NIRCam had detected the telescope's first photons (although not yet complete images).[216][222] On 11 February 2022, NASA announced the telescope had almost completed phase 1 of alignment, with every segment of its primary mirror having located and imaged the target star HD 84406, and all segments brought into approximate alignment.[221] Phase 1 alignment was completed on 18 February 2022,[223] and a week later, phases 2 and 3 were also completed.[224] This meant the 18 segments were working in unison, however until all 7 phases are complete, the segments were still acting as 18 smaller telescopes rather than one larger one.[224] At the same time as the primary mirror was being commissioned, hundreds of other instrument commissioning and calibration tasks were also ongoing.[225]

-

Phase 1 interim image, annotated with the related mirror segments that took each image

-

Phase 1 annotated completion image of HD 84406

-

Phase 2 completion, showing "before and after" effects of segment alignment

-

Phase 3 completion, showing 18 segments "stacked" as a single image of HD 84406

-

Star 2MASS J17554042+6551277[e] captured by NIRCam instrument

-

A "selfie" taken by the NIRCam during the alignment process

-

Alignment of the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope's sensors[229]

-

Webb’s Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS)[230]

Allocation of observation time

Webb observing time is allocated through a General Observers (GO) program, a Guaranteed Time Observations (GTO) program, and a Director's Discretionary Early Release Science (DD-ERS) program.[231] The GTO program provides guaranteed observing time for scientists who developed hardware and software components for the observatory. The GO program provides all astronomers the opportunity to apply for observing time and will represent the bulk of the observing time. GO programs are selected through peer review by a Time Allocation Committee (TAC), similar to the proposal review process used for the Hubble Space Telescope.

Early Release Science program

In November 2017, the Space Telescope Science Institute announced the selection of 13 Director's Discretionary Early Release Science (DD-ERS) programs, chosen through a competitive proposal process.[232][233] The observations for these programs – Early Release Observations (ERO)[234][235] – were to be obtained during the first five months of Webb science operations after the end of the commissioning period. A total of 460 hours of observing time was awarded to these 13 programs, which span science topics including the Solar System, exoplanets, stars and star formation, nearby and distant galaxies, gravitational lenses, and quasars. These 13 ERS programs were to use a total of 242.8 hours of observing time on the telescope (not including Webb observing overheads and slew time).

| Name | Principal Investigator | Category | Observation time (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiative Feedback from Massive Stars as Traced by Multiband Imaging and Spectroscopic Mosaics | Olivier Berné | Stellar Physics | 8.3[236] |

| IceAge: Chemical Evolution of Ices during Star Formation | Melissa McClure | Stellar Physics | 13.4[237] |

| Through the Looking GLASS: A JWST Exploration of Galaxy Formation and Evolution from Cosmic Dawn to Present Day | Tommaso Treu | Galaxies and the IGM | 24.3[238] |

| A JWST Study of the Starburst-AGN Connection in Merging LIRGs | Lee Armus | Galaxies and the IGM | 8.7[239] |

| The Resolved Stellar Populations Early Release Science Program | Daniel Weisz | Stellar Populations | 20.3[240] |

| Q-3D: Imaging Spectroscopy of Quasar Hosts with JWST Analyzed with a Powerful New PSF Decomposition and Spectral Analysis Package | Dominika Wylezalek | Massive Black Holes and their Galaxies | 17.4[241] |

| The Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey | Steven Finkelstein | Galaxies and the IGM | 36.6[242] |

| Establishing Extreme Dynamic Range with JWST: Decoding Smoke Signals in the Glare of a Wolf-Rayet Binary | Ryan Lau | Stellar Physics | 6.5[243] |

| TEMPLATES: Targeting Extremely Magnified Panchromatic Lensed Arcs and Their Extended Star Formation | Jane Rigby | Galaxies and the IGM | 26.0[244] |

| Nuclear Dynamics of a Nearby Seyfert with NIRSpec Integral Field Spectroscopy | Misty Bentz

|

Massive Black Holes and their Galaxies | 1.5[245] |

| The Transiting Exoplanet Community Early Release Science Program | Natalie Batalha | Planets and Planet Formation | 52.1[246] |

| ERS observations of the Jovian System as a Demonstration of JWST's Capabilities for Solar System Science | Imke de Pater | Solar System | 9.3[247] |

| High Contrast Imaging of Exoplanets and Exoplanetary Systems with JWST | Sasha Hinkley | Planets and Planet Formation | 18.4[248] |

General Observer Program

For GO Cycle 1 there were 6,000 hours of observation time available to allocate, and 1,173 proposals were submitted requesting a total of 24,500 hours of observation time.[249] Selection of Cycle 1 GO programs was announced on 30 March 2021, with 266 programs approved. These included 13 large programs and treasury programs producing data for public access.[250] The Cycle 2 GO program was announced on May 10, 2023.[251] Webb science observations are nominally scheduled in weekly increments. The observation plan for every week is published on Mondays by the Space Telescope Science Institute.[252]

Scientific results

James Webb Space Telescope completed its commissioning and was ready to begin full scientific operations on 11 July 2022.

![Star 2MASS J17554042+6551277[e] captured by NIRCam instrument](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/05/JWST_Telescope_alignment_evaluation_image_labeled.jpg/296px-JWST_Telescope_alignment_evaluation_image_labeled.jpg)

![Alignment of the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope's sensors[229]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Webb_in_Full_Focus.jpg/354px-Webb_in_Full_Focus.jpg)

![Webb’s Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS)[230]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Fine_Guidance_Sensor_Test_Image.jpg/196px-Fine_Guidance_Sensor_Test_Image.jpg)